In her article on the closing of Galerie Louise Smit, jewelry historian Liesbeth den Besten painted a rather unflattering picture of the contemporary jewelry market and what she feels is an unbalanced relationship between galleries and artists. Citing the mounting pressures exerted on makers, den Besten ends her article with an appeal to galleries for more transparency, more accountability, and—why not—a charter of fair conduct between galleries and artists. Stefan Friedemann, the co-owner of Ornamentum gallery Hudson, New York, sent us a letter in which he articulated his perspective on the subject as a dealer. His response was published as Part 1 of this series.

Below is den Besten’s answer to Friedemann.

Dear Stefan,

Thank you for your lengthy response to my article about the closure of Galerie Louise Smit. It is important to discuss these issues in public. After Galerie Louise Smit’s sudden ending, artists, clients, and others were quite shocked. The final closure came unexpectedly and was thus badly prepared and broke many individual verbal agreements. Galerie Louise Smit represented some 46 artists.

Let’s start with a small remark. I have come to realize that my article was balancing on two different thoughts, which apparently was confusing and annoying to some readers. My first intention was to write about the closing down of a gallery, how this could happen, and the consequences of this ending, bearing in mind that no gallery is forever and that these shutdowns may occur more frequently in the future. My second aim was to pay attention to the gallery’s history. As Ward Schrijver rightly noticed, I didn’t pay attention to the full history of the gallery, and he filled the gap. In my view, the reasons to start the gallery and the reasons to stop it were the most important issue.

Apparently, readers misunderstood my article as a tribute to Louise Smit, which is only partly the case. As a matter of fact, I was (and still am) more interested in the gallery-artist relationship in general. To me, this looks like a complicated and mysterious matter between two parties: the many artists dependent on one and the same gallery, and the one gallery with this huge responsibility toward all the artists represented by it.

The following response to Stefan Friedemann’s is an elaboration on my initial article and is based on literature study 1 and my own inventory of figures.

Part 1

1. The Galleries

The international contemporary jewelry scene is really tiny. To draw a comparison, the city of Amsterdam, which is a small player in the international art world, counts about 55 fine art galleries. These are quality galleries that offer a platform for new developments in the arts. 2 I know only about 70 galleries for jewelry worldwide, and most of them function in a completely different way. 3 Many are workshop based, focusing on jewelry made by their owners. Sometimes they have a room for exhibitions by guest artists, who are mostly local, seldom international. There are galleries that function like shops, selling commercial brands (watches, industrial jewelry) in addition to showing precious jewelry from preferably local artists now and again. There are only about 21 jewelry galleries worldwide (if we still count Louise Smit in) that deserve to be called vanguard galleries. I am basing my reflections on these galleries and their modus operandi.

2. The Business Model

The owners of the vanguard galleries are often passionate collectors. They start a gallery because they believe in the potential of the contemporary jewelry they love. These galleries promote the ideas of the art they represent, the field as a whole, and the individual artists connected with the gallery. They offer a place where people can meet. The work they represent is not easy. This work requires a good narrative to be sold to clients, collectors, and museums. Gallery owners pick out promising young artists, encourage them, and help financially if necessary to enable them to create a new body of work. They organize at least six solo exhibitions per year. They try to create an (international) market for their artists, find new clients, take care of the visibility of their gallery by participating in fairs, and maintain good connections with critics, magazines, collectors, curators, and other crucial people in the field.

These jewelry galleries copy the practice of fine art galleries to a certain extent. But, there are also differences:

- The group of artists represented by the average jewelry gallery (44) is notably larger than that of a fine art gallery (20). These average numbers are based on my own counting. The number of artists per fine art gallery is based on my counting of 25 Dutch fine art galleries, and it is confirmed by figures mentioned in literature about the subject.

- Jewelry galleries are by definition international—participate in international fairs, represent a respectable percentage of international artists, have international clients.

- A jewelry gallery cannot exist without keeping its stock in directly accessible storage-cum-display units. (Fine art galleries tend to keep their stock behind a closed door, only to be opened on request.)

- The secondary market for contemporary jewelry is poor and underdeveloped. The secondary market describes what galleries, dealers, or auction houses do when they act as agent/reseller of work put back on the market by a previous owner (and not acquired directly from the artist). While there are no jewelry galleries that work in the secondary market, it is precisely that market that helps top international art galleries cover the costs of promoting experimental and/or emerging art (i.e. their primary market). 4

Compared to the fine art market, the contemporary jewelry market is underdeveloped, which is quite alarming, knowing that the first jewelry galleries were established in the 1970s, some 40 years ago. Many people involved are still waiting for the great breakthrough. Nothing has happened yet. Both the primary and the secondary jewelry markets suffer from their position on the margin of the art market(s).

3. The Artists

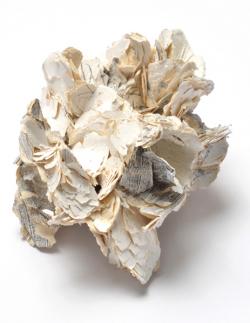

Most artists involved in contemporary jewelry are educated at art academies or art colleges, often piling a Bachelors and Masters education on top of a technical training. In Europe, it is not uncommon for jewelry artists to have studied 10 to 12 years at different institutions. Like fine artists, jewelry artists can also do practice-based Doctorates, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, but also in Belgium, Portugal, and Norway. Jewelers mostly work on their own: they have a studio practice in the classical sense. They prepare solo exhibitions for their main gallery every two or three years. Most jewelry artists have at least three different galleries, but successful artists have even more, up to five or six. On top of this, they participate in group shows and occasionally make work for special occasions (such as a fair) or exhibitions. Sometimes they make a piece for a private commission.

There are hardly any jewelry artists who can make a living from the sale of their work alone. As a matter of fact, I don’t think I can name a single example of a jeweler who is able to do so. This even applies to the bestselling artists. The market for jewelry is simply too small, and the prices are too low compared to the fine arts. Jewelry artists can only survive by having different jobs (preferably teaching jobs, but many need part-time jobs in a different sector to survive), receiving grants, or having a partner with a steady income. They have to work very hard to meet all the demands they face, such as participating in the many exhibitions that are organized worldwide, making work for different galleries, and making special work for a presentation at one of the main art and design fairs. They often live an isolated life and are grateful for any form of exposure they can get, even if they are asked to donate a piece of jewelry to a museum for honor’s sake.

Some jewelry artists try to establish a marketable brand of jewelry—a “bread-and-butter” line—but this commercial model is not very popular among jewelry artists and rarely very successful anyway. A growing minority of jewelers work without a gallery—and for those with other jobs, the main danger is that their jewelry practice becomes an occasional release from the daily job they took on to support it.

4. The Numbers

Twenty-one vanguard jewelry galleries worldwide for 924 artists means an average of 44 jewelers per gallery. The assumption that jewelry artists can easily find another gallery, if necessary in another country, as long as they are good won’t stand in reality. (What is good? Who decides what is good? Are they good if they sell well? Are there other value systems?) The general reality of the art world is that there are too many artists, not many galleries, and definitely not enough buyers. Both artists and galleries are struggling to hold firm, and they feel the pain of this truth. Only the very famous will succeed to keep on going, but for the others, the young ones, the less selling ones, for this majority of artists, there are simply not enough galleries. This has nothing to do with “handling their business of art in a professional or ethical manner” as Stefan Friedemann wrote. It is not because these artists are not professional that they are without a gallery, but simply because there is a limit to the number of artists a gallery can represent. The situation is different if the artist takes the initiative to leave. In this case, he or she has either found another gallery indeed or independently decided to move on. But, is this really “a daily occurrence” as Friedemann writes? As far as I know, both galleries and artists value a good personal relationship, and parting usually feels like a divorce. As in any divorce, we can assume that the one doing the leaving hopes to gain from the separation and the one being left stands to loose.

In the Dutch fine art world, there are many cases of artists who gained attention, saw their market value increase, and suddenly left their first, local gallery in favor of a top gallery in New York, London, or Berlin. This is painful and unjust to the initial gallery that took the risk to work with an unknown artist from the very start of his or her career. Almost 10 years ago in the Netherlands, there was lawsuit of a gallery against an artist (a photographer) because she left the gallery for a more profitable one in New York. The Dutch gallery won the case, and the artist had to pay a considerable amount of money to cover loss of income incurred by his/her ‘ex’ gallery. This situation is unthinkable in the world of contemporary jewelry, which is much smaller and deals with much less money.

Only a few jewelry galleries keep the number of artists they represent very low, about 20–25, which is an accepted figure in the fine art world. We may wonder if these galleries can survive without additional, substantial financial resources from outside. Even the majority of jewelry galleries, ones that work with up to 44 (or more) artists, need an additional income. As a matter of fact, it is not much better in the fine art world (apart from the top tier galleries that combine primary and secondary markets and work with established artists).

Part 2

Reading the responses to my article and knowing about the lamentations of artists and galleries, I get the impression there is a general feeling of disillusion and frustration and a lack of understanding for each other’s position. The gallery complains about artists they suspect of unethical practices, ones that change galleries, or show their new work outside of their primary gallery. Meanwhile, artists complain about percentages, slow payments, and little sales. Be that as it may, both the gallery and the artist emphasize the importance of a healthy relationship based on trust.

1. Ideals vs. Commerce

In spite of the obvious love gallery owners have for their trade and the emotional investment that goes with that, running a gallery is a commercial business. Stefan Friedemann claims that “being an artist is also business,” but I don’t agree with this point of view. It reminds me of the idea of cultural entrepreneurship, which politicians in my own country try to force onto artists. I don’t believe in it. An artist chooses to be an artist because he or she wants to create things that no one ever thought of before. In this process, he or she may well cross the borders of acceptability. It is not his primary job to think if and where it will sell. Of course, he or she wants to sell. He or she needs a living, too. But, like a gallery director, an artist may have a supplementary income in order to survive. When “market thinking” starts trickling into an artist’s practice, we should be alert. Instead, an artist’s focus should be on creating new work because that is his or her reason for being an artist. This does not release him or her from the responsibility to deliver proper work if it is supposed to be jewelry. It should be wearable without falling apart and without the risk of being lost. The gallery, on the other hand, should not be afraid to talk and think about commerce. A gallery is an enterprise.

Today, artists often have more than one gallery, and as Friedemann states “seldom give away the powers they have to a gallery. They own the work and can take it to another venue regardless of how or where the gallery has been promoting it.” I do understand the problem for the gallery, but I don’t suppose Friedemann wants to tamper with the ownership of work that has left the studio. The only solution would be to invest in the work—buy it, become the owner/dealer, and acquire the exclusive rights to promote and sell it. There are some fine art galleries who are in the position to work like this but not in the jewelry world.

And then there are artists who organize, or participate in, events outside the gallery. Through these events, and through their websites, the artists can interact with the public. In my view, this is laudable and inevitable if we want contemporary jewelry to grow and reach other audiences. At the same time, collectors and other interested people love to meet the artist in his studio. They want to understand and feel the process. Nothing is more fascinating than hearing an artist talk while surrounded by his or her materials and fragments of work. This is the other side of the artwork in contrast to its public exposure, which is about the final result, the neatly displayed, the economical, the artwork that becomes part of a deal between seller and buyer. The galleries do not applaud this development because it is “less easy for the gallery to maintain a sense of control on the product/investment, and (…) less easy to justify the gallery going to new lengths and efforts on behalf of the artist” as Friedemann writes. But artists’ initiatives are not necessarily competing with galleries. They can also be seen as something extra, as another way to tickle their audience. Maybe Friedemann is right. Maybe the artist meeting potential buyers through his website, through public events, or in his studio is at odds with the gallery, but it is a development that can’t be stopped. Both artists and galleries should be aware of the implications of the Internet, open studios, and participatory events outside the gallery.

2. Contracts? What Contracts?

Outside of the art world, people are often amazed when they find out that galleries work without contracts. This fact is always explained as inherent to the character of a gallery, which is a combination of an ideological and idealistic approach and a commercial one. But the gallery can’t claim these idealistic intentions as solely theirs, and apparently the idealistic and the commercial also come into conflict. In the 1970s and 1980s, artists’ initiatives popped up out of disaffection with the art system. In Amsterdam for instance, this was quite a strong movement supported by the availability of many cheap squatter places that proved to be great art spaces. Art, music, and dance merged, and pioneers presented video, performance, and other art forms long before these were picked up by the Stedelijk Museum. In contemporary jewelry, alternative initiatives—for instance the exhibitions organized by Schmuck2/Susan Pietzsch, Op Voorraad, Steinbeisser, Dinie Besems’ Salons, and all sorts of temporary events during Schmuck in Munich—were introduced much later and have a different character and effect than those in the fine arts, which is in line with the history and nature of contemporary jewelry as an artistic field. These initiatives are often prompted by the urge to increase contemporary jewelry’s visibility. They offer other ways, trying to reach other audiences. In my view, now is the time for more such initiatives. Galleries and artists must find a way to deal with these initiatives. They must force themselves to discuss the issue and learn how to give and take in mutual agreement.

In my view, a contract or a letter of intent is a way to put down agreements between the gallery and the artist about exclusivity, percentages, payments, professional conduct, the regular production of work, and the regular promotion and exhibition of work. It can lead to a better understanding of each other’s position and responsibility and can certainly help deal with the “special case” of fairs. It is true that the gallery invests enormous amounts of money, time, and energy in top luxury art fairs. But instead of complaining about that, why shouldn’t it be possible to agree on an extra percentage with an artist for selling his work at an expensive art or design fair? Why not make your business more transparent? Why is there all this haze about costs, sales, and investments? Transparency is healthier for everyone.

I do agree that contracts do not offer any safety to the gallery or the artist, but I do think that a contract can offer a situation of clarity and mutual understanding. This, rather than a gentlemen’s agreement, should be the basis for trust, a notion that is so pivotal in the relationship between gallery and artist. It is impossible to anticipate every situation in a contract, but at least trying to write down what is expected of the artist and what is expected of the gallery would make for a healthier relationship between the two parties. By the way, model contracts do exist and are available, for instance from the Federation of European Art Galleries Association (FEAGA).

The article that started the discussion we are now having was written because of the sad loss of a vanguard gallery that made Amsterdam one of the centers of contemporary jewelry. If contemporary jewelry wants to be taken seriously, it should also be open to discussions about the “system of jewelry.” In the art world, galleries and the market are subject of studies, dissertations, conferences, and books. In the jewelry world, gallery directors react as if stung by a bee when a writer makes some remarks on that system. My remarks were not prompted by the idea “that artists are mistreated by galleries,” but by the idea that the gallery and the artist are having a mysterious and less-than-transparent affair. But I have Stefan to thank for giving me an opportunity to structure my thoughts on the subject. I very much intend to continue my research into “the system of contemporary jewelry” and develop this first outline into a more substantial publication.

1 There are many interesting publications on the art world, for instance by Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot, and by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello – these books give a theoretical context to the ‘economies of worth’. My favourite is a recent publication by Jan van Adrichem et al, Positioning the Art Gallery, the Amsterdam gallery world in an international context, Valiz Amsterdam 2012.

2 55 is the number of galleries mentioned in the monthly Amsterdam Exhibitions brochure published by Stichting AKKA in Amsterdam. For unknown reasons, jewelry galleries are not included in the list.

3 This figure regarding the amount of jewelry galleries is based on different sources. I took the list from AJF and compared it to the list in my own book and the galleries I have visited myself or heard about through Facebook and invitations. I visited many websites. From these figures, I deduced the number of 70 jewelry galleries worldwide.

4 According to Olav Velthuis, associate professor with the department of sociology and anthropology of the University of Amsterdam: “In London, Berlin, or New York, the total of additional revenue that galleries derive from their trading activities (on the secondary market, LdB) may amount to more than 50 percent of their total turnover.” (Jan van Adrichem et al, p.183). Jewelry galleries seldom deal in “second hand” jewelry, let alone that it is part of their business model. Today, antique jewelry dealers occasionally deal in high-end contemporary art jewelry by artists such as Giampaolo Babetto and Robert Smit. The rest is sold by auction and via websites. Jewelry galleries don’t profit at all from this extra source of income. The reason for this situation is unclear to me.