To us—that is, those I imagine to be the general audience associated with texts such as this—the idea that the contemporary jewelry field must still be defined or comprehensively explained continues to be topical, as most people outside our small niche remain unaware that contemporary jewelry even exists and has existed for some time. For decades, we have toyed with sociological naming (studio jewelry, art jewelry, etc.) or variations thereof that try to more accurately suggest how the field exists as a reflective creative process. And so, any book hoping to sort through these semantic vagaries will typically dedicate a large portion of its preface to naming the field before any real conversation can be undertaken about the work being made or how it functions in the world.

How effective or wide reaching have these definitions been? In my own experience, not much as is made evident by the reoccurring obligation to explain the objective of my research and my own studio practice to a bunch of medieval historians, immigration researchers, general academics, and even art goers. I find that my own definition for contemporary jewelry is often founded on the utter impossibility to do just that—define—which in my opinion, happens be the field’s most frustrating yet interesting component.

There is one mode, however, through which we have been organizing the work, even if noncommittally so, and that is via the exhibition. Depending on the kind of exhibition or the unifying criteria of the chosen pieces, exhibitions may provide makers with a better platform to introduce themselves, which is worth investigating. As this article will show, the outright purpose of an exhibition may not be to serve individual practice (though the better ones do). Most of the time, exhibitions remain extensions of associative projects and simply pay tribute to a generic form of creativity rather than trying to identify and celebrate specific modes of expression. Be that as it may, exhibitions can be viewed as grouping tools. When curated effectively, they distill facets of the field absent in more general written descriptions. What I would like to do in this text is consider exhibitions as a means of categorizing contemporary jewelry. Can exhibitions help us spell out a clearer message about what we are and help us more aptly dialogue with other art practices? Let’s find out.

In the introduction to his compilation of essays Collecting the New, Bruce Altshuler, director of museum studies at New York University states the following:

“Institutional structures created at an earlier time to meet different needs are being called into question by new artistic media and by the use of the term contemporary to designate a particular kind of artwork. Alternative conceptions of the artwork and new technologies have created special problems of preservation and conservation. Broader social and political changes have generated new artistic categories and have broken down established national and ethnic divisions, all of which have affected how collections are built and their contents organized.” (Altshuler 8)

For the record, I did not use this reference to make the argument that our field should be considered a valid new artistic media to be categorized and exhibited in museums under the guise of contemporary art (although that argument can and should be made). But, I think what Atshuler says about new category generation should also be considered within contemporary jewelry as well. After all, our field has faced similar evolutional changes that have yet to be accounted for.

[This is especially relevant to the way contemporary jewelry is categorized (if it is categorized at all) in museum collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, has contemporary jewelry pieces in their collection, but where are they? The work is basically hidden in the depths of their online catalogue, accessible only if one searches for specific dates or knows the name of the artist. Using “contemporary jewelry” as key words will get you nowhere. As it stands, this descriptive uncertainty not only perpetuates inaccessibility within a collection, but also obscures new associations and exposure to potential audiences, thus contributing to the slowness of our field in relation to other art practices.]

To put things more simply, let me ask you this: how much does, let’s say, Nanna Melland’s work really have in common with work from someone like Graziano Visintin or Doris Betz, beyond the facts that their pieces can be seen on bodies and can be called jewelry?

Looking at past and current exhibitions is one way we can begin to think about breaking down how we consider and value what is being made. It’s like working in reverse. Whether the exhibition initiative is institutional or independent, and even if the distinction between assembling, selecting, and curating is lost on exhibition organizers (as it most often is), sorting through various shows and analyzing the associations being forged between pieces and their authors can help us see more clearly what kind of work exists within the field. If certain exhibition types help us identify subgenres within contemporary jewelry, then makers and writers may subsequently discover better ways of defining the work at hand and explaining it to others.

PART 1

In the following part of this essay, I will discuss what I consider to be the four most obvious go-to exhibition themes broken down into the simplest of terms. These divisions come from situations I have been confronted with as a maker and as an observer of the structures that make up the contemporary jewelry field.

1. All the Objects in this Show Are Made of the Same Thing

Or in other words, exhibitions based solely on material. At times, captivating moments can be found in such shows. Take, for instance, Thomas Gentille’s brooches in the 2012 exhibition Wood presented by Velvet da Vinci (San Francisco, California) or Carolina Gimeno’s enameled neckpieces exhibited in Die Renaissance des Emaillierens during Schmuck 2012 at Galerie Handwerk (Munich, Germany). Both shows featured the work of a large number of makers: Velvet da Vinci showcased 26 jewelers and Galerie Handwerk featured approximately 40 makers. I think this is too many people in one room: the logic of large collective projects gets in the way of detailed mediation efforts. Is it possible that all participating artists equally valued material in the same way? Of course not. Yet, the tremendous work that goes into gathering work from all over the world into a single room is rarely matched by analytical, or at least descriptive, efforts, or a passing attempt to distinguish one maker’s ideas from another. The Museum of Arts and Design’s A Bit of Clay on the Skin: New Ceramic Jewelry is an exception to the rule. The exhibition curator Monika Brugger and the museum staff did a good job of providing supplementary material about each maker’s contribution. The initial presentation of this exhibition in 2010 was even more successful. It took place at The Fondation d’entreprise Bernardaud in Limoges, France, which provided a bigger and more pertinent stage as Limoges is one of France’s oldest and most active ceramic centers.

There were several other exhibitions in the “material” category. Paper Jewellery: Poor Jewellery was shown at the Triennale Design Museum in Milan, Italy in 2009. Studio GR-20 presented Material and Colour in 2010 in Padova, Italy, which focused on work based in minerals and organic and artificial matter (a looser interpretation and more interesting attempt, in my opinion). More recent shows include Emaille Enamel at Galerie Pilartz in Cologne, Germany, and GR-20’s current 30th-anniversary show featuring contemporary works in glass.

Collective, material-based shows rarely let their visitors appreciate the importance of this material choice relative to a maker’s oeuvre. While the material choice is imperative to the success of Ted Noten’s Wearable Gold (2000), the artist only rarely works in porcelain. That this is a departure from the norm for Noten, whereas it is not for Peter Hoogeboom, for instance, is not always made apparent. My point is this—to unite both makers under the umbrella of porcelain jewelry making involves a misrepresentation of actual studio practice.

For all their limitations and for the tenuous conceptual articulation that often characterizes them, material-based shows remain ubiquitous and even banal when they could be purposefully comprehensive and even educational. Why not offer artists a space to outline how they might have rationalized their respective material choice and how that choice may have added to the concept of their work? Surely these choices were not arbitrary. Quite frankly, a lack of adequate framework risks dumbing down the work, especially among the company of many, many others.

2. All of Us in this Show Live in and/or Came from the Same Place

Or simply, location. Working as the field’s tool to gauge who is doing what where, the geographically organized exhibition also functions on a historical level to track the evolution of a region’s aesthetic over time. This in turn allows for the comparison of the work of different international scenes. These types of shows can also function on a local level by informing the general public that jewelers in their area value cultural ties. A good example would be Padua’s annual Pensieri Preziosi exhibition. Last year was its seventh iteration and featured 15 working Italian jewelers, while this year Estonian artists were represented. 4 Padovani e un Torinese presented by Maurer Zilioli Contemporary Arts in Brescia, Italy, (the gallery is also a cultural organization) is another good example. Even though both of these exhibitions were educational on many levels, location is not very helpful in defining creative categories or subgenres of contemporary jewelry. Like all default categories, nationality requires you to do the interpretative legwork on what exactly it makes manifest. All artists working in any genre are geographically grounded in one way or another. National divisions in contemporary jewelry are easily superseded by more interesting similarities in content.

For the sake of demonstrating prevalence, I will randomly list some past shows that belong to this category: Golden Clogs, Dutch Mountains (2007–2008), a traveling exhibition curated by Andrea Wagner; Finnish Bitches (2008) presented by Galerie Louise Smit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; A Pieceful Swedish Smörgåsbord (2011) shown in Munich, Germany, curated by Sanna Svedestedt and Karin Roy Andersson; and Australian Jewelry Topos (2011), Gallery Loupe, Montclair, New Jersey. More recent events include Contemporary German Jewellery at Testa Gallery, Sofia, Bulgaria, and Jewellery from Estonia at Marijke Studio, Padova, Italy.

Exhibitions affiliated with a specific school are also common. In our field, student exhibition opportunities are numerous, sometimes prestigious, and often entail active student participation. I find this quite refreshing and even unique to the way the field functions compared to the art world at large. For example, many shows at Schmuck 2012 were run by students and ex-students, including The Sound of Silver/Brooches para las Chicas by students from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium, and Life’s a Bench, presented by graduates of the Birmingham School of Jewellery, Birmingham, England. A remarkable example, The Fat Booty of Madness: Jewellery at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich: The Künzli Class (2008), was exhibited at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich. Galerie Marzee’s annual graduate student show in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, is worth mentioning, as is PURUS an exhibition of 2012 graduates from Alchimia Contemporary Jewellery School in Florence, Italy.

Again however, this category does not provide a useful stylistic or conceptual banner under which students can rally, precisely because diversity is the hallmark of the better sort of jewelry programs. But at the very least, exhibitions such as Ädellab: The State of Things—presented by Konstfack of Stockholm, Sweden, and showcased during Schmuck 2012 at the Pinakothek der Moderne—provide proof that those included attended a fine art academy. These types of shows create an opportunity for an academy to describe the specificity and vision of their department to the public. Additionally, as in Ädellab’s case, the support of the museum further encourages the notion that the department—and thus the field of contemporary jewelry—is closely associated with fine art. This I would consider to be a win. I’m always on the lookout for a more distinctive overlap or proof that contemporary jewelry and the fine arts can be one in the same.

4. All of the Work in this Show Won a Contest to Be Here

The competition or the juried exhibition provides a different kind of opportunity. Often established to promote work from younger or up-and-coming artists, international events such as Talente in Munich, Preziosa Young in Florence, and the Fondazione Cominelli, also in Italy, are based on that objective but lack a particular focus. On the other hand, some competitions can be thematic, which is a positive attribute to this category. Consider Ritual (2012) and Revolt (2013), both presented by The Gallery of Art in Legnica, Poland, or New Traditional Jewellery (2012) at New Nomads in Amsterdam. Regardless of specificity, juried shows allow artists to indicate that their work deserves the pass of a critical eye and therefore suggest a qualitative hierarchy within contemporary jewelry. Additionally, as in Legnica’s case, competitions push makers out of their comfort zone, and when successful, underline their capacity to produce thoughtful, speculative work. While these competitions often bill themselves as promotional tools for the field at large, their success in this respect is moot, at best. Look at the Schmuck competition. Its existence had, and continues to have, a huge impact on how the field defines itself. But who else out there knows about it?

Although there are aspects in each of the four organizational themes mentioned so far that positively benefit the field, what they have in common is their incapacity either to provide any but the most rudimentary categories or to reach out to new audiences. More intellectual work becomes misrepresented if the show doesn’t respect the complexity of the work. Material-based shows especially run the risk of dumbing down individual practice under a simplistic common denominator. As local and cultural references that may shed light on the maker’s practice are subsumed to an overall agenda, the show becomes a poor analytical instrument. And again, the issue of quantity only exacerbates this. (Material-based shows are not the only culprits of too many makers under one roof.) The more-the-merrier attitude suggests an inability or unwillingness to edit as well as an attitude comparable to carelessness toward the individual object on display and each artist’s vision. Participants deserve better. This is especially upsetting when often very good work deserving a longer inspection is drowned in a sea of stuff. In the past two years I have visited a vast amount of contemporary jewelry exhibitions worldwide, and too often I’m stuck with the feeing of having to get through it all rather than being able to delightfully explore.

Beyond material, location, the school, and the competition, there are fresher independent exhibition endeavors able to bypass the potential rigidness apparent in large group shows, not to mention the distancing and banal display conventions that so often accompany them, such as the glass vitrine or acrylic case. It is beyond the scope of this text to discuss the question of display in contemporary jewelry, but I will include this bit to ponder from Wilhelm Lindemann. In the introduction to Thinking Jewellery, Lindemann writes, “ … charged with the luminosity of the art object exhibited in a display case and the use of the relevant ritual response traditional in the art scene, the adorning function of jewelry as decoration worn on the human body has been obscured … ” (Lindemann 13) This is quite the dilemma that all artists face however, as the path to good exposure and even the humble desire to share is often challenged by limitations innate to the structures of the host institution. At times, this duality can compromise the very role of the object as it belongs to the world of jewelry.

With regards to this, there are quite a few artists in the field that directly scrutinize jewelry’s posturing role as its very nature. This brings me to Part Two, which hopes to be a more compelling list of contemporary jewelry exhibition categories, as ultimately, the previous four do little to provide makers with an interesting conceptual framework for their work.

PART 2

Or rather, display as theme or concept. This is quite a small group, and exhibition titles are at times dictated by the display convention used (and vice versa). Notable shows include Suspended, an independent exhibition at Schmuck 2012, where each piece was literally suspended from the ceiling. On the verge of sounding a bit condescending, virtually any piece of jewelry can be hung from the ceiling, which unfortunately makes the show’s theme an arbitrary excuse to get a bunch of unrelated work into the same room. That’s fine, really, because in the end, the hanging work invited viewers to see all the way around each piece, closely investigate it, and even handle it at their leisure. This initiates a closer relationship with viewers, however fleeting it may be. The exhibition’s second rendition at Schmuck 2013 was a welcomed improvement, as the selection was a little less haphazard, unified by the use of the color pink.

Slanted for Granted works on similar premises. According to the exhibition description found on the Klimt02 website, Melanie Isverding, Despo Sophocleous, and Nicole Beck “ … created for their artwork an adapted context based on directions other than the traditional horizontal or vertical. Objects evolve in another space presented on slanting grey V-shaped boards …” (Transplanted for Granted presentation description) The show originally appeared during Schmuck 2012 and was re-presented as Transplanted for Granted at Vander A in Brussels, Belgium.

Although quite similar to this small category, the next one brings back the role of a single organizer, yet a lot of the time it remains …

2. Things That Look Good Together

A better way to describe this category could be the group show. Exhibitions like these are quite common in our field. The organizers tend to be makers, gallerists, and/or independent coordinators, and are not to be confused with curators. The successful shows usually have two to three participants, and there is little written framework to accompany the show, although a general underlining theme may be presented. Similar to the geographic show, the group show’s success relies on the curator’s selection criteria and his or her ability to put together an exhibition that is greater than the sum of its parts. A noteworthy example would definitely be Schmuck’s annual Returning to the Jewel Is a Return from Exile (now in its sixth year), which includes Robert Baines, Karl Fritsch, and Gerd Rothman. Although the format isn’t exceedingly experimental, one enjoys the fact that their spacious circular exhibition area is heavily staffed. The uncovered jewelry pieces can be picked up, tried on, and intimately admired by the audience.

With shows such as …Dal Silenzio (2012) and Tracce del Passate Nel Presente (2011), Marijke Studio deserves a mention although the work is often confined to glass display cases. At Schmuck 2013, Christian Hoedl organized a show at Schlegelschmuck that fits perfectly into this category. Together, the strong work of Sofia Bjorkman, Benedikt Fischer, Sophie Hanagarth, and Karin Johansson contrasted yet was complementary, while only subtly suggesting some thematic common ground.

Hello there. What is it that you do exactly?

You see. I am an artist who makes jewelry.

Interesting. I have never heard of an artist that makes jewelry. Could you describe that to me a bit?

Well, recently my work was showcased in an exhibition about ________________ with two other artists exploring similar ideas.

And this brings me to my next category.

3. The Shared Interest

For makers who share more in-depth interests, concept-based shows further expose the research element that coincides with any true artistic practice. Conceptual development is fundamental to the field, in which jewelry pieces are physical manifestations of long personal investigations. Exhibitions, therefore, harness the potential to share such thinking processes with the public with statements made stronger when a number of artists gather to articulate their messages.

Because we know that contemporary jewelry is conceptual, this category may seem a bit redundant. It might be better, then, to point out what I would consider the biggest conceptual overlap between jewelers anywhere—work about the body, which we also all know is inherent to the very nature of jewelry. There have been endless exhibitions devoted to jewelers whose work revolves around the physicality of the human form, recognizing that body can be much more than the destination of an object. Keep in mind, however, it can be said that various groups of makers have excavated their own, more singular niche within this vast theme, worthy of its own, more complex breakdown.

Shows about the body are almost as prevalent as those based on geographical location due to the frequency of jewelers who work exclusively with the body as their main concept. Take for instance No-Body-Decoration from the 2006 Preziosa exhibition in Lucca, Italy. Individual artists devoted to the body, the investigation of jewelry’s tactile purpose, and that of wearability include Christoph Zellweger, Lisa Walker, Tiffany Parbs, Lauren Kalman, and so on, yet within this category exist many derivations and interpretations worthy of new subcategories, not to mention enough material for an entirely new text on the subject matter alone. The body has always been a fruitful point of departure, giving jewelers something much more concrete by which to accurately represent themselves. Strong thematic exhibitions are obviously not limited to the body. Any show founded on intellectual content can help distinguish contemporary jewelry from the common connotations of jewelry, which is what we are all after in the long run.

To do this well through exhibition, an apt contextual framework is required. It can be visual or verbal, or more interestingly, a combination of the two. Ruudt Peter’s sensation LINGAM, Fertility Now is a great example of jewelers coming together to share their interpretations of a loaded subject. Moreover, shows that collect jewelers working with existing conceptual similarities already integral to their practice can more clearly illustrate that jewelers are both makers and thinkers. Unfortunately, here’s where things start to get tricky. As far as I’m concerned, these more profound projects are few and far between. Makers’ ideas should be acknowledged and properly reflected in exhibition attempts. Fair examples include: Jewellery Building Building Jewellery (2009) with Sara Borgegård, Erik Kuiper, and Martin Papcun at Platina Galerie, Stockholm, Sweden; Waldeslust with Iris Eichenberg, Hilde de Decker, and Christoph Zellweger at Galerie V&V, Vienna, Austria; BLacK & bLUe (&yellow) (2011) with Paolo Scura and Timothy Information Limited at Galerie Louise Smit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and Taweesak Molsawat: The Missing Elements in Democracy: Art Jewelry as a Political Critic (2013) at ATTA Gallery, Bangkok, Thailand.

Although this is a good list, I would argue that we have a long way to go on this front. Using imaginative and/or unconventional display to draw connections between disparate works by individuals is not the same thing as curating a meaningful exhibition. And speaking of the individual …

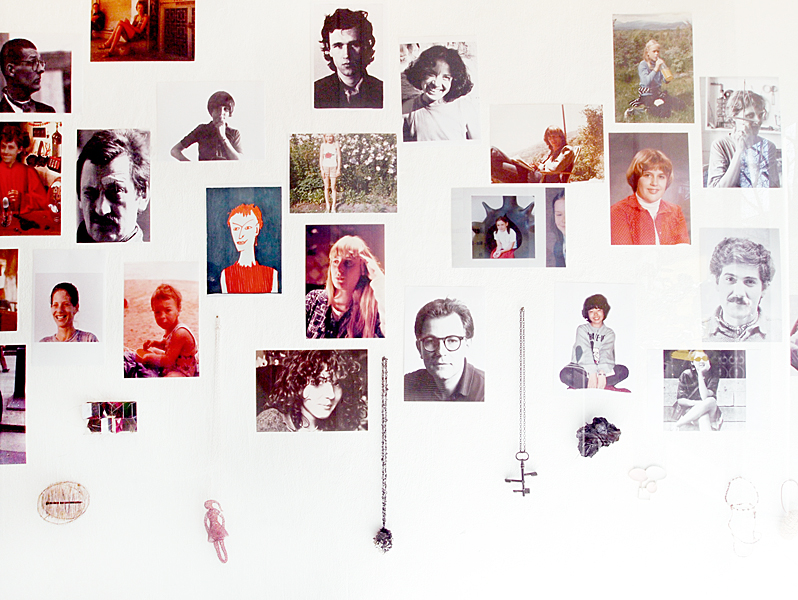

The solo show is obviously the field’s ideal platform for exhibition. Makers can almost do whatever they want depending on the venue … if they are lucky enough to be offered one, that is. My first thought is to cite exhibitions at Galerie Rob Koudijs in Amsterdam. Often, the artist gets free reign, and when done well, display is treated as installation, which can then even be considered the very work itself. Célio Braga’s 2007 installation Possible Jewelry and Related Objects comes to mind, as well as Ruudt Peter’s Corpus in 2011, which was reshown at Galerie Spektrum during Schmuck 2012, this time incorporating an element of performance about giving, receiving, and the church.

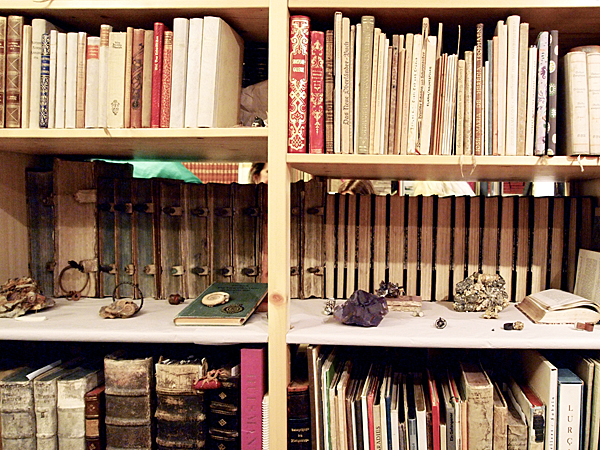

A rogue instance and a personal favorite of mine is Volker Atrops: for No Stone Unturned (Schmuck 2012) and Vintage Violence (Schmuck 2013), he utilized a small antiquarian bookshop as the site for exhibition. His show-turned-treasure-hunt displayed pieces subtly resting on books or nestled with various objects and papers throughout the space, romancing the pursuit for a personal connection between object and visitor. I felt as though I was searching for what might have already belonged to me.

The retrospective also falls under the category of solo show, with the Museum of Arts and Design’s exhibition Margaret De Patta: Space-Light-Structure leading by example. Historical and contextual information was provided, including Constructivist pieces by László Moholy-Nagy, sure to encourage new associations and dialogue outside the realm of jewelry. Efforts of social and cultural attribution should be taken into consideration more often with any type of show, and we shouldn’t have to wait until someone dies to see it happen.

Alternatively, makers have been known to take things into their own hands and create ambitious surroundings for their work that aim to facilitate the understanding of their unique approaches.

The disguise exhibition steps outside our field’s tendency to isolate itself from the rest of the visual world. Independent ventures, liberated from logistical limitations or spatial restrictions have popped up all over the place. Here, the line between the physical and the theoretical are blurred, and visitors can begin to see the relationship between object and experience more easily. Ted Noten’s be nice to a girl, buy her a ring (2008), consisting of a vending machine installed at the entrance to his atelier, is a cute yet smart example. More ambitiously, Hilde de Decker has built a reputation on inviting audiences into the jewelry world through the back door with the Boer work, a project that is, as Liesbeth den Besten writes, “far bigger than jewelry but never turned its back on it.” (Den Besten 54) Additionally, de Decker’s On the Move project displayed works that only suggested a relationship to jewelry.

Trans-disciplinary events fall under this category, including David Bielander and Michelle Taylor’s jewelry and photography collaboration Gente di Mare (first exhibited in Munich followed by Maurer-Zilioli in Italy in 2011) and Still Jewelry by Hanna Hedman and Sanna Lindberg (presented by Silke & The Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium, 2011).

Most of my personal interests in contemporary jewelry exhibitions rest in the disguise category. I see it as an exciting bridge off the contemporary jewelry island, reaching toward not-so-distant horizons in the fine arts where we ought to find new audiences. Consider (non-jewelry) artist Markus Schinwald’s installation in the Austrian pavilion at 2012’s Venice Biennale. As described by the Vernissage TV blog, Schinwald’s work “investigates the psychological relationship between space and the human body,” tampering with the physical encounter of an object and utilizing a combination of classic portraiture and the adornment of constrictive jewelry-esque objects. I imagine the dialogue surrounding Schinwald’s work could easily relate to someone in our field, such as Elisabeth Altenburg, whose interests similarly include, according to Manuela Schlossinger, the “involvement of the human body with corresponding objects … under parameters she sets.” (Schlossinger 1) I do not see this type of connection as a stretch. The art world and our kind of jewelry should be considered inextricable.

The previous categories I have established through various types of exhibitions can only be considered products of an exercise about physical organization. Although some groups provide a bit of verbal aid, they remain generally insufficient as tools in the development of a more specific contemporary jewelry language. Perhaps the lack thereof only demonstrates that those in the field don’t necessarily care about how their work is classified; they just enjoy making and they’d like to leave potential associations up to others. And that is OK. But for me, part of my role as a participant in this field is to support and promote other artists, thus a clearer and more specific use of naming would be beneficial rather than using borrowed terminology from a field that barely recognizes our presence in the visual art world (e.g., “modern” jewelry, “figurative” jewelry, “abstract” jewelry).

A New Approach

There are a couple ways we can do this more affectively. The first one is to fine-tune our exhibitions so they bolster the work on display. Bucks n’ Barter (Schmuck 2013), a trans-disciplinary exhibition about the human tendency to trade, exchange, perceive, and relate to capital and material culture, was an excellent example of what I am talking about. All the work exhibited was strengthened from being amongst the company of the group, and the ideas of the artists were therefore highlighted. They also produced an impressive press release full of information about how the artists came together, why, and with what contribution. With this event, the artists gave themselves a lot of descriptive meat to work with. Let’s try another hypothetical dialog now. You fill in the blanks.

Well, it was nice chatting with you, but I really must be off. I’m in a hurry.

Where are you off to?

I have an exhibition opening with some other young artists.

Oh, lovely. What kind of exhibition?

It’s called _____________ , and it explores ideas about ___________________________. I, myself, have been working with __________________________________.

(Then, perhaps mention something about jewelry.)

Purposefully creating a more specific descriptive language to define what it is we’ve already been doing is the second way we can begin to exalt contemporary jewelry, or at least begin to level the playing field. The Bucks n’ Barter exhibition was initiated by Beatrice Brovia, Nicolas Cheng, Friederike Daumiller, and Katrin Spranger—four of the nine participating artists. This show is especially worth citing as the organizers recognized that the success of contemporary jewelry can be too dependent on mediation, as is the case with other more complex artistic practices. This affects the quality of the message and how it may be received, as we, too, at times, are an equally complex artistic practice worthy of new categories with which to describe ourselves, such as Altschuler previously suggests.

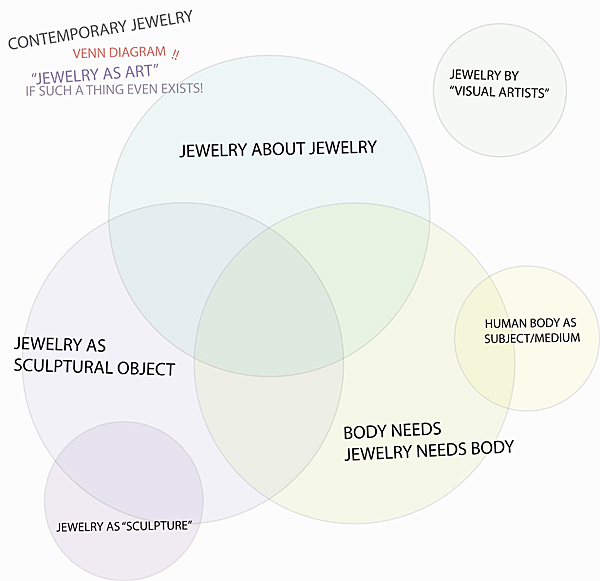

With that said, I will leave you with the following diagram filled with new categories I have developed as possible progress. (This is perhaps the beta version!) Place your favorite jewelers where they seem to fit best, and stay tuned.