Galerie Rob Koudijs plays a critical role in the Dutch jewelry community. Rob Koudijs responds to some questions posed by Kamal Nassif.

Kamal Nassif: What do you hope to achieve with your gallery? How do you measure success?

Rob Koudijs: We think contemporary jewelry is a great medium. For more then 30 years, jewelry artists have managed to surprise us and tempt us to buy and wear their work. With Galerie Rob Koudijs, we have the opportunity to support the careers of artists who have excited us for many years and to introduce new, fresh, and promising talents. We enjoy contributing to the development of this field immensely!

We are very proud of finding a new and younger audience for this art form in spite of the commonly uttered fears that galleries have had their heyday and that collectors are “on the verge of extinction.” We feel this is not true. We are playing an important and an essential role as a promoter of contemporary jewelry. It is crucial that this kind of promotion continues. Hopefully, the future will see the start of many new galleries with young owners to continue the good work.

Kamal Nassif: In your latest publication of the GRK Magazine, Ward Schrijver’s essay discusses the pending “unequivocal acceptance” of jewelry into the greater scope of fine art. Describe the steps you are taking to achieve this acceptance. What can the community of gallerists and artists do to help?

Rob Koudijs: Unfortunately, there is no general institution that decides these matters, so all you can do is be as visible as possible.

Galerie Rob Koudijs is in a high profile area of Amsterdam from the perspective of general shoppers and art gallery visitors. We attend important art fairs; always maintain a good, up-to-date website; write introductions and publish our magazines; very actively work with museums; and we act on any serious invitation to participate in projects or requests for information. (We receive these from all types of design- and art-related websites.)

Getting jewelry in public museums and mentioned in articles and reviews in newspapers, magazines, and websites is probably the most essential way of promotion. The whole jewelry community should put their efforts to this goal! (AJF is already very important in this respect.)

Kamal Nassif: What voice do you feel your publications have in the larger discussion of contemporary jewelry? Who is your ideal audience?

Rob Koudijs: In general, the publications contribute to the feeling that this is an art form and a gallery to be taken seriously. Unfortunately, we haven’t yet seen angry or overly excited people at the door or people who wanted to donate money for the good cause.

Of course, we intend the magazines for our customers and visitors to the gallery, but the best result would be if they would draw the interest of the famous “general public.” So, we hand them out to everyone who is tempted or who is a potential decision maker.

Kamal Nassif: All too often, discussions about contemporary jewelry stay within the community of people who have a prior awareness of the field. I am curious, what do you sell to somebody who has no notion of contemporary jewelry or even of fine art?

Rob Koudijs: We sell them what appeals to them. If you don’t fall in love with a piece—whether it’s small and cheap or spectacular and pricy—it has no use. If someone is new to the field and they are open to it, we show them the width and depth of the medium and the excitement it can bring. If they just want to drop in, buy, and leave quickly, it’s OK as well. We’re sure that one day they will return.

Kamal Nassif: And in that same vein of thought, how important do you think it is for a buyer to understand the conceptual content of a work?

Rob Koudijs: Everybody makes up their own story with a piece; everybody has their own personal associations. So, even if they don’t understand anything of the intellectual content of a work, they can still be utterly happy with it. (This is the case in all fields of the arts). The artist, the gallery, and the customer can all be content. But of course, the more the conceptual idea is understood, the better (naturally, that’s our aim)—and the more profound the satisfaction is for everybody.

Kamal Nassif: Do you feel there is a dialogue between your gallery and the other jewelry galleries in Amsterdam? If so, how would you describe your role?

Rob Koudijs: Well, now there is just Galerie Ra. We’ve known each other for more than 30 years, and we have a good professional relationship. We both have our own profile, and whenever it’s necessary, we have contact or work together. The same goes for Galerie Marzee.

Kamal Nassif: Amsterdam is something of a hub for contemporary jewelry. Do you feel any special obligation to represent the diverse body of work from your own backyard?

Rob Koudijs: We do the best we can for all the artists we represent in the gallery. If something exciting turns up in the Netherlands, we’re always keen to be “on the ball.”

Kamal Nassif: The interior of your gallery has an organic color scheme with wood accents. It is markedly different from the other Amsterdam galleries. What led you to make these design decisions?

Rob Koudijs: We never thought of it as organic. We just wanted to create an inviting, pleasant atmosphere in which the interior design would not distract our visitors. Everything is aimed at presenting jewelry to its best advantage.

This might come as a surprise to you, but Ward Schrijver, who designed our interior, was also responsible for the design of Galerie Sofie Lachaert in Gent, Belgium in 1990, the Gallery Ra interior in use from 1992 to 2010, and the redesign of Gallery Louise Smit in 2002. He designed many art fair booths for Marzee, Lachaert, and later for Smit as well as numerous jewelry exhibitions in museums. As always, every era has its style and every principal his or her own wishes.

Kamal Nassif: And now something I have always wondered: why the green accent wall? Is there any particular significance of this color?

Rob Koudijs: The decision to use a color came from the rather haphazard articulation of the existing wall. Coloring one element gave it structure and rest. The color came from the ink color chosen by our graphic designer for our house style. She picked it as an approximation of the color of gold. There is nothing more to it.

Kamal Nassif: If you had to describe your collection in one sentence, what would you say?

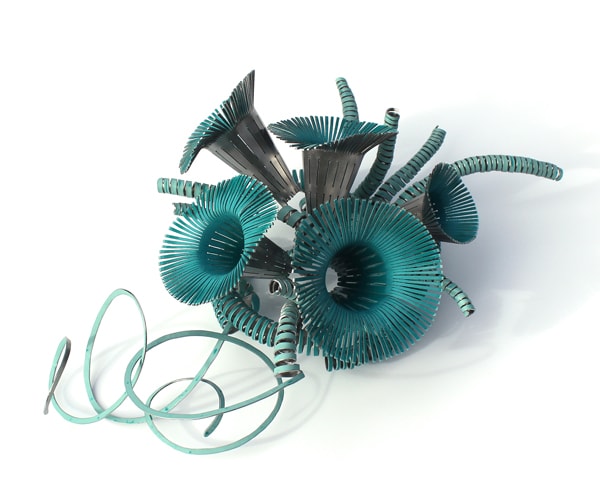

Rob Koudijs: Innovative, sculptural works of art enhanced by the presence of craft and technique that can almost always be worn as jewelry.

Kamal Nassif: What have been your biggest challenges since opening in 2007?

Rob Koudijs: To improve on all the fields mentioned above.

Thank you.