Ursula Ilse-Neuman is Curator of Jewelry at the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York. Recognized internationally as a writer, lecturer and curator, she has worked at the museum for over two decades and in that time, has organized a great number of exhibitions on contemporary jewelry and the wider field of craft. Her most recent exhibition, Space-Light-Structure: The Jewelry of Margaret De Patta, co-curated with Julie M Muñiz from the Oakland Museum of California, continues to receive acclaim on both sides of the continent. Ilse-Neuman’s April 2012 presentation on De Patta at SOFA NY can be found on AJF’s website. Damian Skinner joined Ms Ilse-Neuman recently for orange juice and gravlax and had the chance to ask her some questions about herself, the Museum of Arts and Design and collecting art jewelry.

Damian Skinner: Tell me about your background. How did you come to be working at the Museum of Arts and Design?

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: I would have to say hard work coupled with serendipity brought me to MAD. When I was pursuing a graduate degree in the decorative arts in the Cooper Hewitt/Parsons Masters program, one of my professors asked me and several other students to work on an upcoming exhibition at the American Craft Museum, the forerunner of the Museum of Arts and Design. Around that time, the museum had been planning an exhibition on the Weimar and Dessau workshops of the German Bauhaus, but it was proving difficult to get the objects together. Janet Kardon, who was director at the time, sensed that my German background made this project a natural fit for me and charged me with rescuing the exhibition from a long history of missteps. It was a baptism by fire. Dessau and Weimar are important repositories of the early craft-oriented Bauhaus work but getting national treasures out of what was still East Germany and into the United States turned out to be impossible. In the end I found examples of the objects we wanted for the exhibition from private and museum collections in the United States. My most memorable experience was in Dessau where Konrad Püschel, a former Bauhaus student, invited me to his home and over coffee and cake, regaled me with stories of his student days and gave me important insights into how the Bauhaus actually functioned.

After the Bauhaus exhibition, I went on to curate exhibitions in all the traditional media, traveling the country to meet such icons as Wendell Castle, Garry Knox-Bennett, Sam Maloof and Beatrice Wood. Being born and raised in Germany, the history of American craft was a revelation and very different from the German experience during the twentieth century. Almost immediately I fell in love with this unique and exciting field.

And when you say all the traditional media, do you mean craft?

Yes, the traditional craft media: wood, metal, glass, ceramics, fiber, mixed media – I did them all. I organized a retrospective of Garry Knox Bennett’s furniture, a major exhibition of international art quilts that traveled to the Tokyo Dome and Taiwan, ceramics by Gertrud and Otto Natzler, glass from the Czech Republic featuring Libenský and Brychtová, as well as many other well-received projects. I take great pride in these exhibitions and the publications produced to accompany many of them. Publications are an enduring legacy after the close of an exhibition.

So why did you decide to focus on jewelry?

Because it is a passion, pure and simple. With each jewelry exhibition, I became more immersed in art jewelry. As a European – especially one whose hometown is Munich, where jewelry is celebrated – I began to dream of being the contemporary art jewelry emissary for the museum and even for the country. Finally, four years ago, after the museum had changed its name and moved into its new building at 2 Columbus Circle, the museum director offered me the newly created post of Curator of Contemporary Jewelry, the first such position in this country. I was very happy to accept.

And when you say you love art jewelry, what does that mean?

I love the fact that contemporary jewelry has meaningful content – it is about social and political, philosophical and existential issues of great importance today. I love the experimentation and innovation, too. Craftsmanship and mastery of materials and techniques are critical and artists frequently introduce cutting-edge materials and techniques to create new and highly expressive forms. I love seeing traditions transformed or subverted. And I love the idea that contemporary jewelry is not pure ornament but introduces concepts related to the human body and psyche and frequently addresses ideas prevalent in the visual arts today. One of the most rewarding and enjoyable aspects of my role is getting to know jewelry artists. They are very special people and I admire their dedication and how they are able work in a small, intimate format to express big ideas.

Do you wear a lot of jewelry yourself?

Not a lot, but I do collect a bit and I always wear the jewelry I collect. My pearls and my grandmother’s jewelry rarely see the light of day now.

Who made the jewelry you are wearing today?

I practically live in Eva Eisler’s eminently wearable necklaces and brooches. She’s a Czech jeweler who lived in New York for many years but has now moved back to Prague, where she chairs the Metals Department at the Prague Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design. My enameled silver earrings are by Todd Pardon, the son of Earl Pardon. I recently acquired some pieces by Mieke Groot, a Dutch glass artist and jeweler and I am fortunate to own several works by Thomas Gentille, a New York artist who has contributed a great deal to my passion for jewelry. Our discussions and visits to galleries and studios to look at jewelry together have been invaluable to my appreciation of the field.

So what is the place of jewelry within the museum?

Jewelry occupies a very important place at MAD. We have the only permanent gallery expressly for contemporary art jewelry in the United States and we are very proud of it. We were fortunate to have the support of the Tiffany Foundation when we worked on the plans for the new jewelry gallery on Columbus Circle. The gallery incorporates all of the museum’s dreams. It allows us to install temporary exhibitions and at the same time keep a substantial part of our permanent collection on view in drawers that visitors can open. We change the selection of works in the drawers every few months and it surprises and delights people to get a sense of our holdings. We also offer computer access to our entire collection so visitors can do their own research right from the gallery. The studios on the sixth floor are a highlight, too. Accomplished jewelry artists are invited to work in these spaces and discuss the jewelry they are making with visitors. And, of course, we regularly offer workshops where people can learn a range of jewelry techniques and come away with their own creations.

How do you deal with the problem of jewelry oftentimes being for the body and a museum being a place without the body?

For me, the idea of jewelry as being originally designed with the body in mind is sufficient; it doesn’t necessarily have to be wearable or be seen on the body. I even like to see jewelry presented as a metaphor, as in Jeff Koons’s oversized jewelry-inspired sculptures that may represent luxury, or perhaps wretched excess. I think jewelry is far more interesting than it gets credit for. I also like to see jewelry in context. MAD doesn’t have extensive historical decorative and fine arts collections or photography collections that can be shown alongside jewelry, so this requires getting loans from other museums, as well as from galleries and private collectors. In the recent De Patta retrospective, for example, I borrowed several important works by De Patta’s mentor, László Moholy-Nagy, the founder of the Chicago Bauhaus, where De Patta studied for a period in the forties. And we also showed films made by Moholy-Nagy and we got these from his daughter, Hattula, who heads the Moholy-Nagy Foundation in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Without these contextual pieces, the extent to which Moholy’s Constructivist ideas permeated De Patta’s works throughout her career could not have been made clear.

Does MAD focus on jewelry that is handmade and on craft processes?

Not handmade per se. That would have been true earlier in the museum’s history. While we still concentrate on one-of-a-kind objects, today’s artists and craftsmen are constantly innovating with new technology and incredibly exciting work is being done with rapid prototyping, with photographic manipulations and with laser cutting. The materials and techniques employed today go far beyond those mastered by traditional craftspersons working in wood, metal, glass, ceramics, or fiber. Jewelry artists today are exploring uncharted waters.

Nevertheless, we continue to maintain a strong interest in process and craftsmanship. A very important part of our jewelry collection dates from our origins as the Museum of Contemporary Craft in 1956. Aileen Osborn Webb, the museum’s founder, became involved in helping American craftsmen in the 1940s, at the start of what is now recognized as the studio jewelry movement, so our collection was formed around pieces by such legendary American jewelers as Art Smith, Sam Kramer, Margaret De Patta, Claire Falkenstein and Ed Weiner. This was a uniquely American scene, totally different from what was going on in Europe in the forties and fifties, yet so important to all that followed in this country and internationally. It always surprises me when jewelry experts from Europe or Asia have little knowledge of mid-century American jewelers.

How big is the museum’s collection of contemporary art jewelry?

We have about 700 art jewelry pieces in the collection now, with three times as many promised gifts coming into the collection in the future. Promised gifts are bequeathed to the museum during a collector’s lifetime and are then signed over to the museum at some future date or at the end of life. Generally, we have the right to borrow these promised gifts as they are needed for exhibitions.

Why would people not give the work straight away?

Because they want to continue to wear the jewelry and that’s quite understandable. We have researched these collections and know we want them, even if we have to wait.

So you are interested in working with collectors to develop the collection?

Yes, of course. All of the museum’s curators work to enlarge the collections. We always aim to keep a balance in the different media. We all have special people, friends of the museum, who are stalwart supporters and have repeatedly come through with pieces for the collection.

What would you tell a collector who was interested in knowing what MAD is looking for in terms of contemporary jewelry? What would be of interest to you?

Basically, we are interested in collecting work from the end of World War II to the present. We acquire some contextual pieces from the arts and crafts movement or other historical periods, but our main focus is contemporary jewelry from all over the world. I am always looking for innovative ideas, where the concept is carried out through masterful craftsmanship, whether the materials are precious or nonprecious. Before a new piece enters the collection it will be carefully scrutinized, not only by me, but an entire committee whose members have to approve of the new acquisition. I have a huge wish list that I regularly update to keep it current. Several years ago, I initiated a strategy to collect the models, sketches and working drawings artists used to create the pieces we collect. I am particularly proud of the many contributions artists have made and the insight these materials provide to the creative process when shown together with the jewelry.

What is the museum’s collecting philosophy? How do you wish to represent people within the collection? One good piece? A number of pieces to characterize their careers?

It varies. Sometimes we select an example from a particular period of an artist’s work. For some well-known artists, we may acquire several pieces from various stages in their careers. This is particularly relevant of artists who have made substantial contributions to the field over extended periods of time, including Arline Fisch, Robert Ebendorf, David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw, Gijs Bakker and Otto Künzli. And there would be many more.

So there are no formal restrictions governing when someone’s jewelry can be considered for the collection?

No. Of course, an artist’s reputation plays a part. I think immediately of Hermann Jünger, Francesco Pavan, Giampaolo Babetto and Annmaria Zanella from Europe, or prominent American artists such as Jamie Bennett, Bruce Metcalf and Thomas Gentille, to mention only three, or historical figures including Margaret De Patta, Art Smith and Sam Kramer. Of course, we seek out their finest examples for the collection. But we also want interesting and surprising pieces of high quality from Asia, Latin America and Africa, as well as from lesser-known and emerging artists. In this regard, I really do want to be more adventurous.

That’s an interesting issue. At what point does it seem appropriate to collect the work of a younger maker?

I work hard to keep abreast of the field and to follow the careers of younger artists to see whether they continue to progress. Each March, I religiously make a pilgrimage to Schmuck in Munich to become acquainted with international trends and emerging talents and, closer to home, I regularly attend gallery openings all over the tri-state area. I also crisscross the country to participate in jewelry symposia and art fairs, including SOFA. Recently, I participated in JOYA, the Contemporary Jewellery Week in Barcelona, where younger international artists presented and discussed their work and where several jewelry schools, including from Brazil and China, participated. Since this is a dynamic field, energized by jewelry programs around the world, I also try to keep up on the latest developments through the internet – Klimt is a great site. It’s non-stop learning.

I think I have acquired an understanding of what has good potential and enduring value, what doesn’t; what is maybe just a one-night stand, so to speak. I consider concept, craftsmanship, whether similar work has been done by the artist’s peers or predecessors. If geographic distinctions are apparent, I consider them, too, although nowadays artists are connected globally and making a national or geographic distinction is often not possible. All these factors play a part in the selection process –as does the allocation of funds for a purchase.

What are your upcoming contemporary jewelry projects?

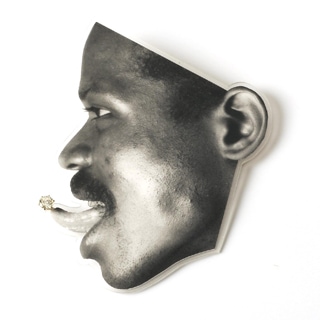

Currently, I’m organizing a large exhibition of jewelry that includes or relates to photography. This is going to be a remarkable exhibition. The artists come from all over the world and their work is exciting and up-to-the-minute. Basically, they turn nineteenth-century photo jewelry on its head. We will include some of this early photo jewelry for context – daguerreotypes, tintypes, miniature portraits, mourning jewelry – but the main thrust of the show is contemporary: artists who take photo jewelry where it has never been before.

Do you think the infrastructure of contemporary jewelry is healthy? What is it like being a curator at the moment?

Contemporary jewelry has gained great international momentum and is gaining greater recognition in the United States, thanks to museums like MAD through its continuing leadership in collecting contemporary jewelry and championing the creative process. Thanks also to people like Susan Cummins and Helen Drutt and others who have been instrumental in supporting the field. It’s still very much a field that deserves a wider audience and we all have to work together to make this wonderful form of artistic expression more visible and better understood. I look forward to even better times ahead.