DesignLab #11 | LithoMania

January 20–April 3, 2022

Kunstgewerbemuseum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Germany

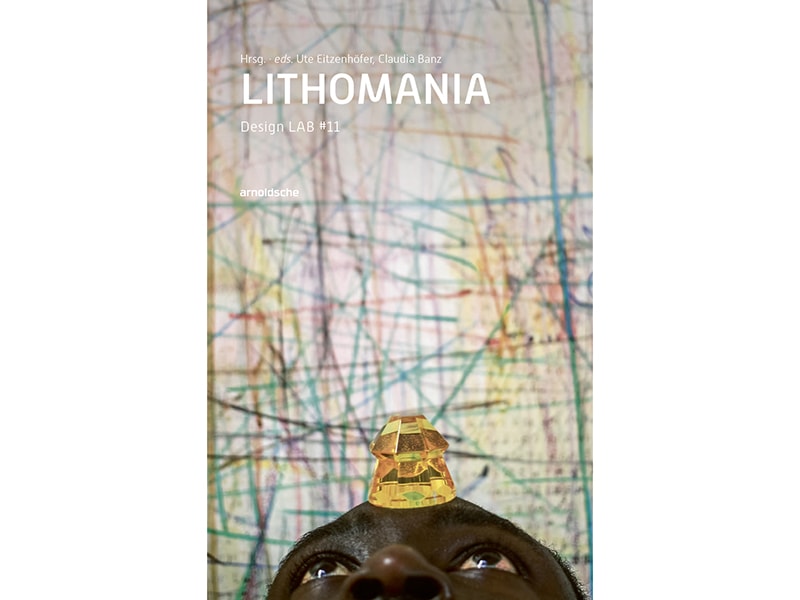

Claudia Banz, Ute Eitzenhöfer (eds), LithoMania Design Lab #11, Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2022.

In the exhibition LithoMania, gemstone and jewelry students from Idar-Oberstein look from a distance at their primal material, the gemstone. They ask questions full of curiosity and criticality about it. They leave room for the tension between the glorious and the grim sides of stones. The funny observations are at the end, so no one leaves with a heavy heart.

Many facets

An obsession for stones, that is how you translate “lithomania.” At the university in Idar-Oberstein, Germany—on which the exhibition focuses—lithomania is a common condition. International students work with precious stones and jewelry in innovative and experimental ways. Curator Claudia Banz, of the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin’s museum of decorative arts, invited these stone-obsessed students for a collaboration. She frequently asks outsiders to comment on the museum’s design collection, which can be seen as a material archive.

Each participant explored the interaction between humans and stones, not through jewelry but through sketches, objects, and installations. LithoMania is not just singing praise. Greed, the harmful consequences of extraction, and human aggression are all part of the mix. Just to illustrate the confusion, the show includes a jade auction recorded on TikTok Live.

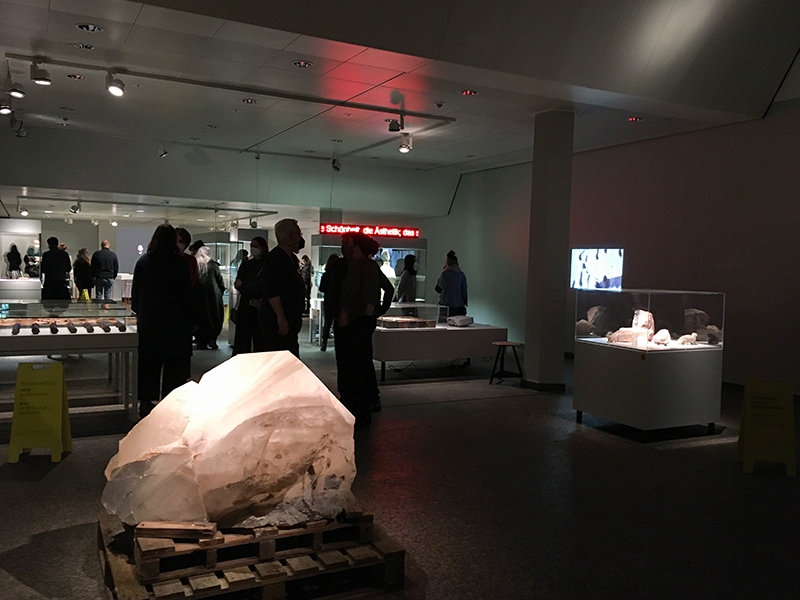

Let’s walk through the exhibition. An impressive 1.32 kg piece of quartz welcomes the visitor in the main hall. Insured for $45,000, it is on loan from a trading company in Idar-Oberstein. Quite a tangible example of the material at hand! Further along, interviews filmed with Idar-Oberstein stone workers portray a certain kind of craftsperson, one who thinks, eats, and breathes stone. This is how the work of the Belgian Peter Vermandere entered the exhibition. His polyurethane Petrophores figurines have stones for heads.

Human technology

From the Kunstgewerbemuseum collection itself there is a ninth-century reliquary bedecked with pearls and gems. A few floors up in the museum you’ll find a room full of these medieval masterpieces. To have this one isolated invites closer inspection. It introduces a history lesson of how humans have mastered nature. In the stones on the gold cross, nature’s or God’s light shows through the cabochon cut. Later technical victories, such as faceting, managed to bring yet more light into the stone. The latest freeform cuts don’t need God anymore, just outstanding tools.

Also from the museum’s holdings is a collection of Berlin cobblestones. The variety of colors in the locally sourced rocks confronts our ignorance of what lies beneath our feet. In the installation Unfinished/finished we look at animal figures hewn out of stone, in various stages of the process. It plays with the time scales of the stone cycle and the human lifespan. Here the human hand—part of nature, too—acts the part of corrosion by sun, rain, and ice. Why, when we see a stone, do we feel there is a job to finish that nature has left unfinished?

A slippery slope

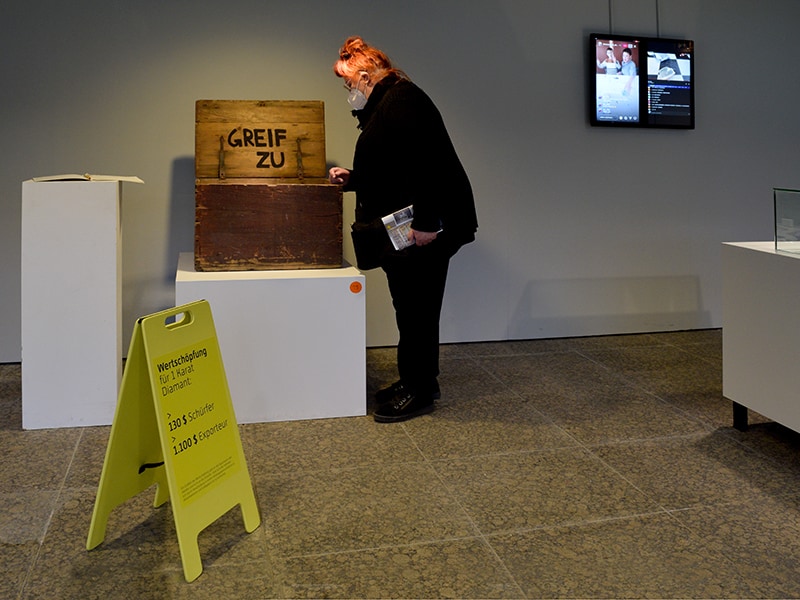

Everywhere on the floor, “slippery when wet” signs ask for attention. First, they seem like cheerful yellow specks in this slightly dark basement. But then it hits us. What exactly should we be cautious about? Data. Sophia Kron gives us the hard facts.

The year 2002 saw 4,000 deaths due to mine collapses in the province of Kasai, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, compared to 199 deaths from traffic accidents in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a similar number of inhabitants. In 2022, up to 10,000 children and adolescents are working in Sierra Leone’s diamond mines. Another fact: 90% of gemstones are mined in developing countries and sold in industrialized countries. And another: Producing 1 kg of synthetic ruby takes 1,700 kilowatt-hours, about the amount of current a one-person household would use in one year.

Other installations tackle similar topics. There is a film loop of a German mining landscape, a 1.5-tonne explosive blasting away 10,000 tonnes of rock. Next to it is a showcase with the scarred landscapes of surface mines, made to scale in the precious stone that these quarries delivered. The work next to it refers to Namibia. To live on so-called blue ground—diamond-rich soil—is not always a blessing but more likely a death sentence. Could a colonialist attitude still be ingrained in the extraction of precious minerals?

What to think of a table full of stone penises? These are no fertility symbols, nor are they Wilma and Fred Flintstone’s naughty toys. Did you ever stop to think that stones are used for stoning? Nioosha Vaezzadeh observes that men and women are treated differently. Mainly it is the men who stone, while the women are the ones being stoned.

A weapon and a cure

Toward the end, the spiritual side of stones is made tangible, drinkable even. Three water dispensers with various crystals in them sit on a bar. You make a wish at the one that feels right, pour a drink, absorb the energy, and see what happens.

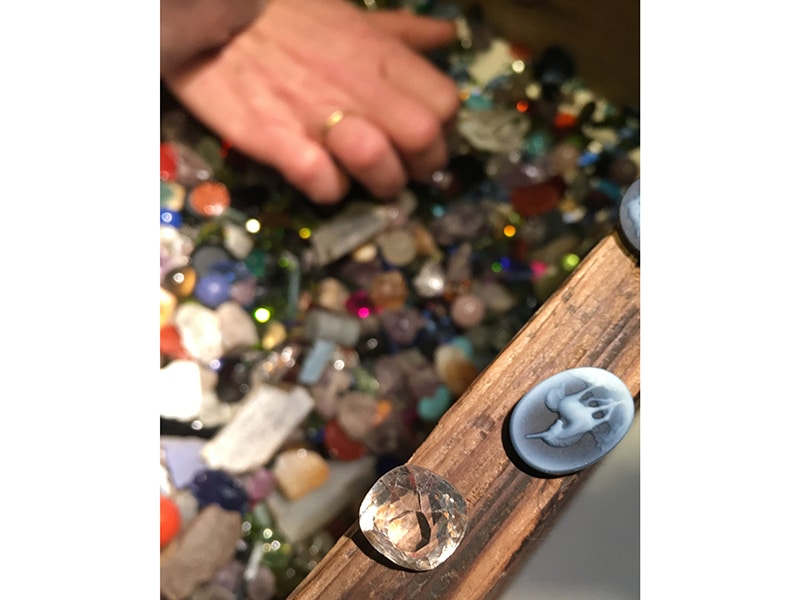

The piece that no visitor will skip is the treasure chest, filled to the rim with raw, synthetic, tumbled, faceted, and engraved goodies waiting for you! But when you pick one (how hard it is to pick only one!), you are asked to write down the reason you chose that particular one. While “greed” might be the honest answer, I jot down that my child will love that fairy cameo.

Is there no jewelry to be seen at all? Of course there is, the school has also left its business card. Around 25 small glass cases show striking work by alumni such as Edu Tarín, Nga Ching Ko, Ignasi Cavaller, Elvira Golombosi, Pia Groh, Patricia Domingues, Vesal Bahmani Nik, and Jiun-You Ou. The collective of fresh graduates, “From the Jauntiness of Absence,” has a vitrine for their dreamy studies. Among them is lapis lazuli that looks like chamois leather, its “stoniness” denied completely.

Do not disturb

The academy where all this emerged is six or seven hours by train from Berlin. Idar-Oberstein is tucked away in a valley along the Idarbach. This stream made the grinding mills run when agate was once mined there. During that period, the art of stone cutting was perfected. Later, agates came from South America, and still later other stones from elsewhere around the world found their way to the town. The stone-working skills only got better. Almost every building houses a wholesaler, a stone grinder, or a gem trader. It’s a fact: The best gemstones and the best gem cutters find each other here.

The town seems a bit introverted, a place out of time. This might be true of the academy, too. The head of the department, Theo Smeets, likes to paint a picture of an isolated, almost dull working environment with nothing else to do than completely surrender to the time-consuming task of working stone. Could this withdrawn state be connected to the fact that the academy was not a place where one asked questions about ecology or social sustainability? Nonetheless, some students made it a point to use only rejects and debris from local stone workers. A few graduated without using stone at all. But in general, until recently the academy hardly stirred under the rising ecoconsciousness of the jewelry world.

Identifying the dilemmas is a big change. The LithoMania exhibition tries to think them through, without providing answers. I wonder: Will some gemstones like lapis lazuli become suspect? Do 100% transparent supply chains exist at all? Should we use up the stones that we have and stop mining anything virgin? Still other questions hide just around the corner in the show, without being posed literally: Can a student ever use a stone with a foggy provenance again? Should the university at Idar-Oberstein close shop?

If it does, we still have the book produced in tandem with the show, LithoMania Design Lab #11.

A desirable book …

The academy in Idar Oberstein produces a steady stream of scrumptious publications (how do they do it?), such as Neuer Schmuck aus Idar Oberstein (NSAIO). These usually showcase student and alumni work. The accompanying essays are written by a more or less regular crew: Ute Eitzenhöfer, Julia Wild, and in-house art historian and living gemstone encyclopaedia Wilhelm Lindemann.

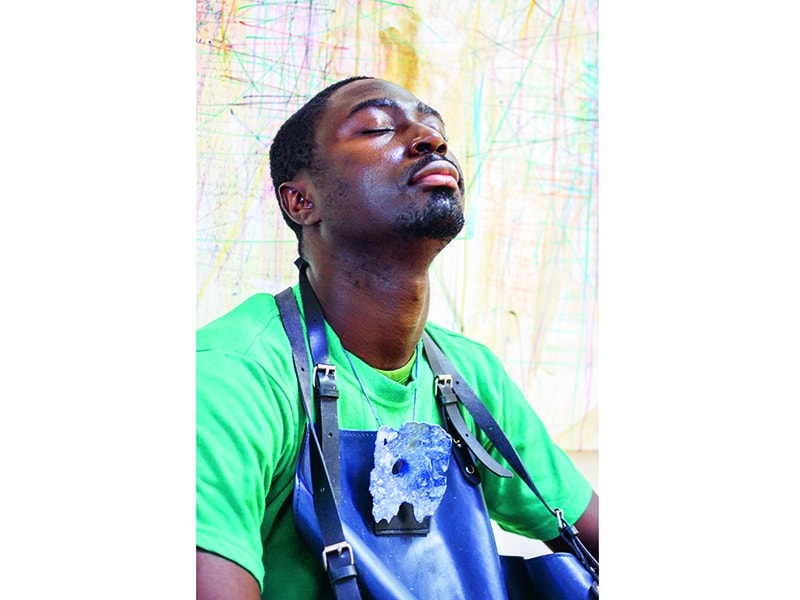

LithoMania Design Lab #11 is no exception in its desirability. Stunning full-page photographs give an impression of Idar-Oberstein. The spot where chunks of amethyst are carelessly used to fill holes in the masonry. The pitch-black shaft of a slate mine nearby. Images of the stone-cutting process. An apron stained as if with blood from a red jasper. A wholesale yard chock full of crates holding precious stones. And the result of the hard labor, of course: the unconventional jewelry and objects made by the participants and their fellow students.

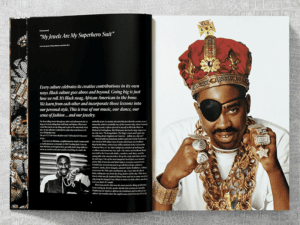

Quotes from those same students about their personal connections with stones are sprinkled across the pages. This brings a previous book to mind: ROCKstars. The principle of brief, intimate associations proves to be infinite. The desire to possess a stone, the hint that a stone has a soul of its own, the submission to a fracture, they are all there. However poetic they may be, the quotes make the book look inward. Even Nioosha Vaezzadeh, with the strong, feminist statement she gave about stoning in the exhibition, keeps her book quote personal instead of political. Exceptions are Sophia Kron’s and Sandra Hartman’s factual passages about injustices in the global stone trade.

… that leaves some stones unturned

The center of the book, printed on different paper, holds five essays. Will they shed light on the forms that the “reciprocal relationship between man and stone” can take, as Julia Wild said to introduce the exhibition? Will they pause at the tension between physical appeal and the burden of knowing the downsides of stone extraction? Will they —? Well, not quite.

Ute Eitzenhöfer writes an interesting piece on time scales and the stone’s claim to eternity—until the moment it is worked into smaller and smaller bits. Julia Wild, who hails from Idar-Oberstein, examines why she does not feel the same excitement for stones as newcomers to the town do. In a touching account, she wonders if she has felt too much dangerous grinding dust, seen too many not-so-unique carved products waiting around. What does fascinate her are the cultural ties that still exist with Brazil, where so many Idar-Obersteiners migrated due to the stone-cutting trade.

The longest essay is classic Wilhelm Lindemann: A well-researched account of how stones appear in Greek myths, in Pliny the Elder, the Bible, and so on. If this is supposed to sort out the ambivalent feelings facing Lithomaniacs today, it is a bit of a winding approach.

Unexpectedly, in a different essay—the last in the book—Lindemann does speak out on something contemporary. He vividly defends the use of synthetic stones on the grounds of artistic freedom. And he says that artists should find a new nature-friendly way of dealing with resources. This should start by “perceiving nature beyond instrumental objectives.” Spot on, but how? I am ready to find out. But Lindemann has already taken another lyrical path, observing how in the interior of a rock crystal the detail and the whole come together.

Only with writer Claudia Banz, the host of the exhibition, do words like “conflict material,” “(neo)colonialism,” and “hierarchies of control and domination” enter the pages. “Materials are therefore always political,” she writes. It seems her fellow authors took a lighter touch, possibly in an effort to not close the door on free artistic expression. LithoMania Design Lab #11 is a truly beautiful book, rich in images and rich in information. But don’t expect a catalog of the exhibition. It is the actual installations in Berlin that address the thorny issues. More than the book, they make you think. And as long as there is sound thinking, there is no reason to close shop yet.

Additional information

DesignLab #11 | LithoMania was curated by Claudia Banz, Kunstgewerbemuseum, and Theo Smeets, Idar-Oberstein Campus of Trier University of Applied Sciences.

Participating students: Ana Bellagamba (MX), Natascha Frechen (DE), Sandra Hartman (NL/ET), Mana Jahangard (IR), Biljana Klekachkoska (MK), Sophia Kron (DE), Felicia Mülbaier (DE), Gina Nadine Müller (DE), Elias Neuspiel (AT), Helena Renner (DE), Constanza Salinas (CL), Miriam Strake (AT), Nioosha Vaezzadeh Angoshtarsaz (IR), Lisha Wang (CN), Ye Wang (CN), Luisa Werner (DE) and artists Carolin Denter (DE), Levani Jishkariani (GE), Bernd Munsteiner (DE), Peter Vermandere (BE), and Cornelia Wruck (DE).

See a PDF of some of the book here. It was published by Arnoldsche.

See more