As a curator of contemporary art, I am used to going to art fairs: Not to collect per se—even though I am always looking for acquisitions ideas for the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, or MAMVP), where I work—but to actually meet with gallerists and colleagues. Those somehow obligatory trips are always useful to prepare exhibitions and to see the usually good institutional shows on view. But since I have lately been more involved with decorative arts (I organized Decorum/Carpets and Tapestries in 2013, and I am preparing Medusa, a show around jewelry, both at the MAMVP), I now also go more systematically to the design fairs often adjacent to the main art fairs. Those generalist design fairs are very different from others like Schmuck in Munich, SOFA in Chicago, or Joya in Barcelona, which are solely dedicated to craft or jewelry.

Even if the art world is somehow keeping a snobbish distance toward design, some art dealers like the Parisian Natalie Seroussi are standing out, proudly wearing some of her amazing artists’ jewelry while in the booth. I am also always amused by the trend among art galleries to furnish their booths with famous or extravagant designer chairs and tables. I guess every art dealer feels the need to behave like a trend-setter, by showcasing a sort of good and cutting-edge taste. For a fair’s directorship, to give their art audience more design options certainly makes good business sense, but this shift also reflects a conscious decision to create a synergy between the two fields. It all started in Miami in 2005 (hence the name Design Miami) and has to be understood in relation to the design district that this city is planning and investing considerable money in.

Contemporary artists, and more specifically what I would call “neo craft” artists, literally brought me into craft, narrowing, if not annihilating, the so-called hierarchies between the arts: to textile first, and then to jewelry, and to ceramics. This scene is still new to me, exotic, with its own rules and conventions. I enjoy getting to know its actors better: artists, dealers, as well as collectors. Altogether, the scale of the design fairs, their quieter atmosphere, but also the quality of the work on view make every visit as refreshing as it is fruitful.

In June, I attended the two Basel fairs and this text is a small report on how the jewelry scene looked to the art specialist that I am.

Even when I was devoted more strictly to contemporary art, the question of the display always interested me: back then, it was about trying to invent ways to challenge the white cube, exploring for instance the fictional and the domestic.

Now that I am working on Medusa, an exhibition which will mix contemporary jewelry and artists’ jewelry together with more traditional ancient, anonymous, and high-end jewelry, the question of how to exhibit those various types of pieces in an art museum has become quite crucial.

Jewelry is in many ways more complicated than design and decoration, mainly because of its craft side and its codependency with the body … unlike furniture, lighting, ceramics, carpets, and tapestries, jewelry lacks a clear function, and is generally made to be worn. It is also facing all kinds of clichés—especially from an art world perspective— often being pigeonholed as accessory, feminine, superficial, precious, corporeal, or primitive. But, as it turned out, this seems less of an issue in Basel, Switzerland than in France …

This year, out of a total of 36 galleries showing there, Design Miami gathered five of the most renowned galleries specializing in contemporary and artists’ jewelry.[1]This is still a minority, but it is actually five times more than in 2008. Out of those five jewelry galleries, two specialized in artists’ jewelry—Louisa Guinness and Elisabetta Cipriani, both from London—and three in contemporary jewelry—Villanova from Florence, Van Hoek from Brussels, and Ornamentum, from Hudson, New York. This year, a show organized by Lausanne’s museum of decorative arts (Musée de Design et d’Arts Appliqués Contemporains, or MUDAC) around their contemporary jewelry collection made for some interesting overlaps with the jewelry displayed in the commercial fair: The combination of five gallery shows and a museum exhibition offered a rich and contrasted visit, even though there was between them less of a rift than I expected.

Part 1

What struck me first and foremost was that none of these shows seemed to try to compensate for—or even refer to—the absence of the body. At first, it reminded me of the habit of decorative art or primitive art museums, which always abstract the artifacts from their contexts. At the fair, there were no full-size mannequins—only a few busts—no fabric on which jewelry would be attached (which could allude to the body or the clothes without mimicking it), but also very few custom-made displays to present jewelry vertically, as if worn.

Most of the jewelry was actually presented flat, and this seems less of a financial decision (even though the participation costs in Basel are very high) than a conscious, curatorial, position. As pointed out in AJF’s own survey of jewelry exhibition-making,[2] I attribute that to a desire to highlight the conceptual and/or artistic dimension of the practice: From that perspective, the body, references to clothing, suggestions of movement, or even the representation of objects in use, seem to be forbidden if not taboo …

I am aware that dedicated contemporary jewelry collectors do not always wear the jewelry they collect. But that being keenly attentive to their collection’s conservation, they tend to build custom display furniture for them, in dedicated and intimate rooms in their homes. Others boldly integrate them within their art collection, hanging and placing them in their living rooms, among their paintings and sculptures, putting them on view for others.

But for the art viewer that I am, seeing most of those works presented in the fair as self-standing sculpture or decorative object was a little confusing, even paradoxical. I wondered if it revealed a sort of schizophrenia in the jewelry field which, being attracted to art, ends up denying its own self. Both consciously and unconsciously. To better seduce different types of public, and more specifically, the art public?

Part 2

Apart from this common choice of avoiding references to the body, each gallery’s specific identity was in fact reflected in its display choices, in tune, at least apparently, with the types of objects they presented.

Generally speaking, one could say that the two artists’ jewelry galleries used more assertive, artistic, or let’s say more complex, embodied scenographies, while the other contemporary jewelry galleries had chosen more straightforward—even though varied from the point of view of design investment—showrooms.

Louisa Guinness’s booth was the boldest and showed the biggest commitment in its scenographic display. The London gallery, which opened in 2003, specializes in commissioning limited-edition jewelry from fine artists with no jewelry background; she is also a second market reference for selling existing and renowned artists’ jewelry from the 20th century. For the fair, she proposed an ambitious exhibition-themed scenography, called The Museum of Artists’ Jewellery; An Introduction. I always loved the idea of fictional museum displays (in the vein of Marcel Broodthaers’s Musée d’Art Moderne, or Claes Oldenburg’s [Mickey] Mouse museum) because of the institutional critique they constitute. It was sort of interesting, yet risky, to reiterate these strategies in a fair context.

The booth was divided in two sections. On the outside of the booth was a long traveling vitrine built high up into a wall, with a glass table next to it; the gallery also painted the walls in an Yves Klein blue and used a felt of the same blue—now her signature color—to complement the gold of the jewelry. Her initials were added to the booth in a neon light.

In this first museum section, Guinness featured rare “mini sculptures” made between 1935 and 2016, presenting well-known names in a meticulously chronological order—Giacometti’s Sphinx and Max Ernst’s Groin by pioneer metalsmith Pierre Hugo, Fontana’s lacquer Conceto Spaziale edited by Giancarlo Montebello GEM editions, as well as pieces by Man Ray, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Louise Bourgeois. She concluded this timeline by placing herself in its continuum, with her own recent projects with Anish Kapoor or Yinka Shonibare, among others. In those fictional museum cases, works were presented on fancy yet minimal bases and bore museum labels detailing, in addition to the artists’ names, the references of the editors and makers, at least for the historic pieces.[3]

The second part of the show—inside the booth—was called “The curator’s office.” Even though it clearly looked “behind the scenes,” I first took it to be a jewelry studio or workshop. There was a hook for white blouses, a table covered with leather skins, some vintage lights, wood and metal archival drawers, as well as archive materials and books on the artists on display placed on library bookshelves (both decorative and practical). The jewelry in this office section was not organized chronologically but was gathered in groups of works by each artist (examples included Line Vautrin, Catherine Noll, or Sophia Vari). It was also more accessible, more hands on (reminding me—in a vastly improved version—of the MAD displays which are hard to handle because of their proximity to the ground). This section indeed functioned as an “undercover” showroom, inviting viewers to manipulate the pieces, interact with them, and possibly try them on in front of mirrors before hopefully buying one of these, as the press release stated, “affordable and wearable pieces of art.”

The degree of scenographic realism was as high as the museum-quality ambition of the selection. However, because of this ambiguous curator’s/dealer’s office space, I was not sure which museum it intended to mimic: One could argue that it might be because such an artists’ jewelry museum does not exist yet. The subtitle of this exhibition—an Introduction—suggests that this was a first attempt to make the minds evolve, and reduce the borders between art, design, and the applied arts. I actually thought about Duchamp’s book, Prière de Toucher (Please Touch), from 1947. I also wondered if his Boîte en Valise (a portable monographic retrospective in a suitcase) could not serve as a model to display the mini sculptures, acknowledging the crucial question—for jewelry—of reduced size and scale. But such a choice might have diminished the power and, indirectly, the value of those objects.

Elisabetta Cipriani, the second London “wearable art” gallery (open since 2009) specializes in jewelry (usually one-of-a-kind) made by contemporary artists. She was presenting a solo show by the Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei, focused on a recent piece, Rebar in Gold. The work, made in 24-karat gold, refers to the 2008 seism where 70,000 people, including many school students, perished in Sichuan Province, due to local buildings’ poor construction techniques. This malfeasance happened to be largely caused by the local government’s negligence and corruption.

It took Cipriani “three years to conclude the deal,”[4] she said. Two straight 20-cm- and 60-cm-long golden bars were presented in individual vitrines, on A4 or A3 pieces of paper, to emphasize, I quote, that they “are more artworks than jewelry”; I actually thought that the sheets looked like gift-wrapping paper. In any case, each golden bar is aimed to be easily custom-bent to suit one’s wrist (becoming hence a unique and almost participatory work, following a strategy that recalls Ted Noten’s Chewing Gum piece). The two similar glass and huali wood[5] cabinets were designed by the artist to resemble the shape of the houses that tragically collapsed. Probably in anticipation of attacks criticizing his recuperation of a tragedy turned into an expensive commodity, the artist stated that “life is precious; the piece is all about respect for life.”[6]

Next to this solo booth was a second space, where the office table was: Cipriani chose to present, in white wooden rectangular vitrines that looked like drawers flipped up vertically, some of the collaborations she made with other artists like Giorgio Vigna, Adel Abdessemed, and Jacqueline de Jong. Captions merely consisted of the artists’ names, written in pencil on the wall. She told me, “I wrote an artists’ wish list in 2009 and I am still working on it … most of them accepted and I thought of others, too!” Notable was the absence of protective glass, which is “different from our gallery set,” she offered, “more accessible.” Those perpendicular drawers functioned like deep, open frames for 3D objects, and it is interesting to note that Cipriani and Guinness, the two London galleries, explicitly foregrounded easy access and manipulation in their display strategy.

Antonella Villanova, based in Florence since 2008, chose to present two solos by artists she just started to work with. One was the British, Glasgow-based Peter Chang, a recognized, yet alien, figure in the contemporary jewelry world, whose flamboyant, pop, and almost sci-fi resin bracelets—on white shelves—greeted you as you walked toward the booth. Next to him was the Tuscan Monica Cecchi, showing colorful pieces mostly made out of recycled materials. There were also some glass works, plates and vases, from the Alchimia collective, which provided a counterpoint to the jewelry. Behind these, individual boxes fixed onto the walls showed individual and flat presentations of works by Ralph Bakker, Peter Bauhuis, Jamie Bennett, and Manfred Bischoff, among others. In short, the gallery had chosen the “clear legibility” of the white cube. And it was actually rather simple. I would indeed never criticize an art fair gallery booth for not having a special scenography (I even tend to be annoyed by a booth being too baroque), but I realized, as I left her gallery, that I was probably unconsciously expecting more of a scenography from a design fair booth, because of its design focus. But it should not be automatic. At the end, isn’t a fair booth a showroom supposed to promote neutrally the artists you represent in order for them to “fit” any body or interior? And Villanova’s booth choice served quite well the pieces she presented.

The division between a solo and a more hotchpotch selection was also the option chosen by Ornamentum, which has specialized since 2002 in the “conceptual side of contemporary jewelry and related art and objects.”[7] Its co-director, Stefan Friedemann, is one of the rare male dealers on the jewelry circuit, and his is the first jewelry gallery to have been accepted into Design Miami back in 2008, and to have entered Basel in 2011. He said he was “happy that there are now five galleries in the fair. I feel less of an exception.”[8] And as he noticed, “each of the selected galleries’ identity is really original.” I liked that he did not reject all artists’ jewelry—as is often the case in the contemporary jewelry field. He even referred to Ai Wei Wei’s as a good artist’s jewelry example. The crucial question for him, he insisted, is “never whether the artist made the piece himself or not; I just judge if the work functions as jewelry, rather than being the reduced version of an existing artwork.” I totally relate to this fair statement. But the reality is that those “reduced” sculptures are often, for art specialists and art collectors, the means to discover contemporary jewelry. I also think that sometimes, being an outsider of the jewelry field can produce very interesting pieces.

On the left inside of his booth, he organized a condensed, yet ambitious, 50-year retrospective of the seminal German contemporary jeweler Gerd Rothmann: Dozens of his early plastic pieces were displayed on a long wood table, together with his later signature fingerprint works, as well as an impressive skull cast standing sculpturally, by itself, in a vitrine. Rothmann is well known for work duplicating selected parts of the body in the positive or negative. Like Ruudt Peters or Christoph Zellweger, he can thus probably handle better than others the absence of body references in the exhibition space, but he constantly plays with it. In this case, for instance, one of the booth walls featured a huge poster of a black and white photo of a blurred woman’s profile revealing an ear piece glowing in a stellar-like reflection (this photo was also reproduced in the artist’s monography and in the booklets that the gallery publishes on a regular basis).

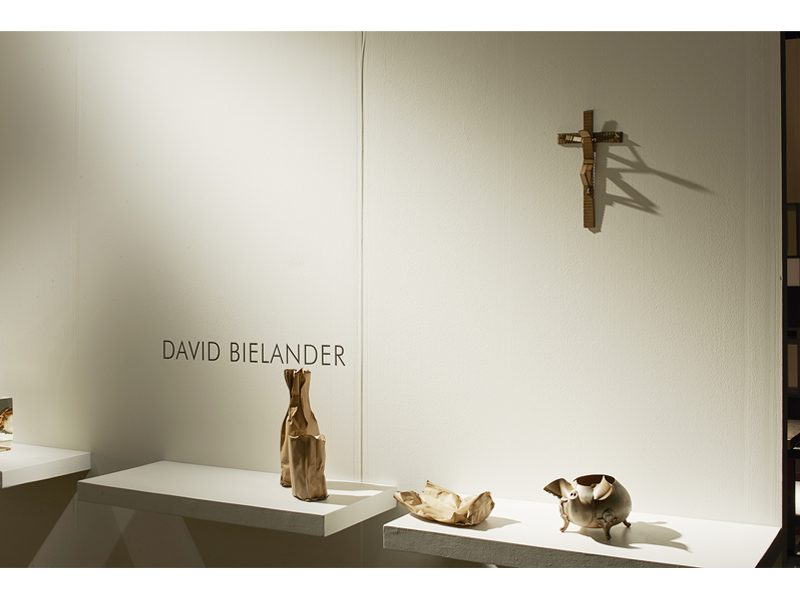

In the second half of the booth, Ornamentum had its usual and efficient system of drawers, in which I caught glimpses of the work of some of the gallery’s other fair “stars”: some architectural necklace pieces by Annelies Planteijdt, impressive Plexi objects by Ted Noten, and a brand new Jiro Kamata series. Everything was presented simply on trestle tables, almost nothing was under glass. And there was no table, not a single seat for the dealer or the collectors. Some of David Bielander’s popular trompe-l’œil pieces, fabricated from gold made to look like cardboard, were hung on the wall, attracting many curious visitors. Meanwhile, Karl Fritsch’s delirious rings were stuck, in his usual playful and iconoclastic way, in plasticine. The subtle variety of Ornamentum’s display proved, once again, that a conceptual approach is not antithetical to humor and subtle provocation.

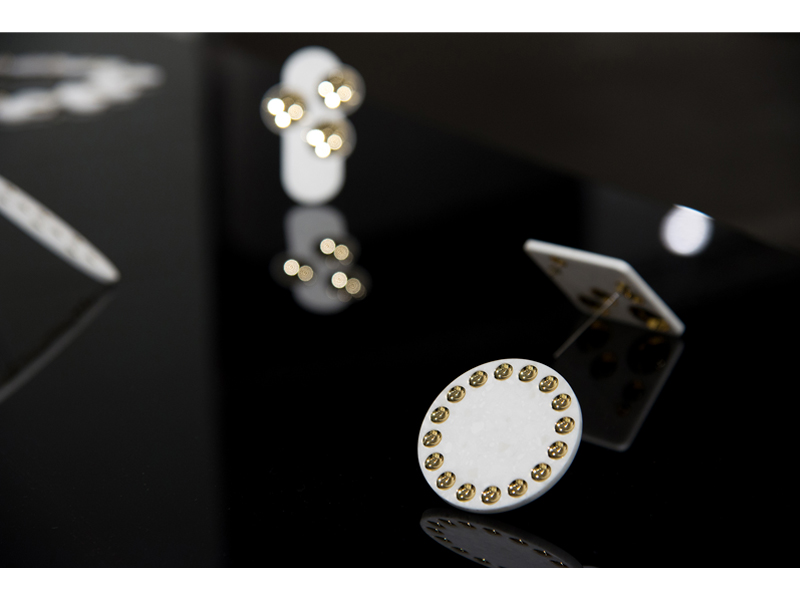

Also recognized for its owner’s conceptual approach to jewelry, yet way more designed, was the booth by Brussels’s Caroline Van Hoek, whose gallery opened in 2007. Various small tables with sophisticated display systems put different pieces in dialogue. Everything looked thought through: the choice of sophisticated materials—the marble, the fabric for the cushions, the square or round glass lids, the metal, and the integrated and focused light—created some angular, almost constructivist and dynamic compositions in a rather dark space, one that was more theatrical than any of the other booths. The resulting effect was of very coherent unity, despite the confrontation of very different works. Van Hoek was also the only dealer who hung some of the necklaces vertically in mid-air, and even though the body was absent, they looked as if they were abstractly worn. They also looked like self-standing, autonomous complex sculptures.

The selection was stringent and elegant, and there were no labels to identify the pieces, because, she explained, “I am working with a stable list of artists.”[9] Year after year, her clients and visitors are invited to a sort of blind date that demands some assiduous guessing-game from them. I enjoyed recognizing works by the Padovan master Giampaolo Babetto, and the South-African Daniel Kruger, or the great Dutch Gijs Bakker.

When I asked why the glass structures had no tops, she said that it was “easier to take a piece out” … but the display nevertheless created a sort of intimidating distance, an aura.

When I praised her for making a successful group presentation while avoiding the “showroom feel,” she reminded me that she had also presented solo exhibitions (Ruudt Peters, Lisa Walker) in previous editions of the fair. I also remembered her great homage to Manfred Bischoff (who she does not represent) the year he passed away.

I asked her if, in addition to art and design collectors, some students or artists were coming as well. She was positive: “Yes, and they sometimes bring or send portfolios and I always look at them. Sometimes it even gives birth to further collaboration.” That was nice to hear. As I suppose no Basel art galleries would ever say so, much less take the time to look at portfolios during a fair.

In addition to those galleries’ booths, there was, for the first time ever, in another section of the design fair, Bijoux en Jeu, a contemporary jewelry museum show organized by MUDAC’s curator Carole Guinard. The show featured more than 200 works—almost the entirety of the MUDAC and the Swiss confederation collections—spanning from 1962 until today, comprising mainly Swiss contemporary jewelers. The show questioned the meaning and the uses of jewelry and showcased a broad range of materials and techniques.

At the end of a large industrial building in Halle 3, a very long (more than 30 m) and narrow table was divided into five linear and thematic sections (Dire, Parure, Utiliser, Donner Forme, Faire)[10] inherited from Parures d’Hier/Parures d’Ici: Incidences, Coïncidences, an exhibition curated at MUDAC by Guinard in 2000 with Marie Alamir. According to Guinard, this mode of presentation is “more pertinent than any other chronological or alphabetical order.” The arrangement was rather subtle, with detailed scientific labels, and the work’s placement raised at least one question: many objects could have been part of different sections and their presence, here or there, depended on which aspect of each work the curator wanted to stress the most (a few artists appeared with several pieces in different categories). Guinard’s intent was that the viewers wonder about each choice, and, as she said, that they consider jewelry from a different perspective.

I was impressed by most of the pieces, including work by Max Fröhlich, the Swiss master influenced by Bauhaus; Johanna Dahm’s T-shirt brooches; Zellweger’s unsettling prosthetics; Bielander’s animals; and Guinard’s own “stolen jewelry”—her urban photographic series from the 1980s. I was also glad to discover they had a necklace version of Bernhard Schobinger’s broken bottles, a Verena Fuchs butcher-paper piece, and great work by Sophie Hanagarth.

Here again, the pieces were lying flat. Guinard told me she hated “metal stands/bases.” I argued that they are sometimes useful: helping to understand a piece, or show the back, etc. She had thought of an alternative solution: On a wall in the back, she hung a series of black and white photos of the works on display, commissioned from students of the Vevey School of Photography at the Centre d’Enseignement Professionel de Vevey. It was great to see those museum pieces circulate, tried on, worn on younger bodies, outdoors, in nature, in the snow even: it made them look very accessible and more meaningful at the same time. It was also quite discrete and did not overinterpret the pieces on display.

Differently from the five commercial booths, the MUDAC showcase was sealed by a glass top, as any manipulation is obviously contradictory with the museum’s conservation and surveillance policy: Museum pieces are not for selling, neither are they for stealing.

Compared to the galleries’ presentations, this one definitely reflected an urge to construct meaning and reflection—thereby fulfilling the museum’s mission for transmitting knowledge—rather than offering just individual presentations or aesthetical group gatherings. But the MUDAC’s minimal yet thoughtful display was actually perfectly supporting its pedagogical goal: It was as if the pieces were readable, from left to right, as on a scroll or a storyboard. The result was both visually and scientifically convincing, and the linearity of the display did not curtail the meaning of the exhibits.

Guinard was very pleased with the audience attendance and the show’s reception. Yet Ornamentum’s Friedemann was the only dealer who said he had seen the show; the other galleries all said they had been very busy in their own booths.

Conclusion

The five dealers I met on that last day of the fair said that they sold to both design and art collectors—including many newcomers—and were keen to come back next year. Cipriani even concluded that the “artists’ jewelry market is booming.”

This boom might have several explanations. It certainly echoes the “neo craft” trend that we observe in the contemporary art world, which can be understood as a reaction to the growing virtualization of our times. It also logically follows the recent recognition of the role of the decorative arts in the invention of modernity. It could finally be seen as a symptom of a bigger and fetishistic attraction for “miniature sculptures” that are much more affordable than the deliriously priced artworks shown at the main fair next door.

I left deeply convinced—even more so after this visit—that good contemporary jewelry and artists’ jewelry are not only more interesting than simple commercial jewelry, they are also more than simple autonomous sculptures—in part because of their link and codependence to the body. And I am interested in the strategies used to display their differences and strengths. This Miami design fair showed a variety of inventive presentations that were both assertive, and not literal. I nonetheless came out of the fair thinking that the emancipation of jewelry should not necessarily have to translate into the negation or denial of the body. And so I look forward to seeing if contemporary art’s infatuation with the body will impact craft’s own reflections on display, to beget yet a new alternative to the white cube …

INDEX IMAGE: Gerd Rothmann, Schädel (Skull), 1978, silver, formed to the head of A. D. Trantenroth, 230 x 150 x 145 mm, photo: artist

[1] Unlike the NY Spring Masters or the Collective Design fairs, there was no vintage-studio type jewelry, nor high-end jewelry.

[2] Benjamin Lignel, ed., Shows and Tales: On Jewelry Exhibition Making (Mills Valley, CA: Art Jewelry Forum, 2015).

[3] This information was missing for the projects she produced herself on the label, which are often made in London’s famous Hatton Garden, as stated in the press release.

[4] All quotes by Elisabetta Cipriani from a conversation with the author, Basel, June 19, 2016.