Eighteen-year-old Patina Gallery was an early champion of European studio jewelers and has been particularly adept at creating cultural synergies with the vibrant local scene in New Mexico: For the second year in a row, their summer exhibition features work made specifically by Peter Schmid in response to the Santa Fe Opera’s program. The German master riffed on Don Giovanni with a striking palette of blacks and golds, and gallery director Ivan Barnett, as per usual, turned the opening into a dress-up extravaganza. He kindly took the time, in the midst of quite a hectic setting-up schedule, to respond to my questions.

Benjamin Lignel: Patina is located in Santa Fe, which to most of our readers will evoke the flamboyant colors of New Mexico. What is the city’s historical relationship to studio craft, and how does the community support it today?

Ivan Barnett: The first studios in Santa Fe were truly those of the native Pueblo artisans some centuries ago. I take a very purist view of studio craft. Santa Fe has had a history of “makers” in clay and metal, wood, and textiles. In Native cultures there isn’t a word for art.

The region has produced some of the most renowned artisans in modern history. The black pottery of Maria Martinez, for example, is coveted by museums around the world, bringing prices that would tip the scales of any current studio maker. Just a week ago I was in the home where so many of her works were made some 60 years ago. The tradition lives on in her relatives, who are still making works in her artistic tradition.

Fast forward. Georgia O’Keeffe, who lived and worked just an hour away from Maria’s studio, began making contemporary clay sculpture in the 1970s and 80s. The Tate in London is now featuring a one-person show of Georgia’s works.

In the jewelry arts, as soon as the Spanish settled the area here, more than 400 years ago, the master silversmiths introduced their craft to Navajo makers, and ushered in a whole new era of excellence. Jewelry making took hold with the village people. This month, that culture of makers will converge in Santa Fe for the region’s oldest “craft market,” Indian Market; it is almost 100 years old.

Fast forward again to the 1960s. Anglos started opening art galleries in Santa Fe, and many artists from around the globe started setting up studios here. Another level of studio craft occurred. Famed dealers in what we all consider contemporary art started showing and selling “craft.” Charles Loloma, who redefined Native jewelry, and Lloyd Kiva New, the genius behind the Institute of American Indian Arts, became some of the first to encourage studio artists. In the 1970s, Elaine Horwitch established one of the first studio fine art and craft galleries in the exact location Patina now occupies.

Fast forward again. In the 1980s and 1990s, a new breed of studio craft galleries came onto the scene. Okun, LewAllen, Craftsman, and Jane Kent were the best galleries from that era. In 1999, Patina arrived.

The 1,000-year arc of history is intact, and the amazing thing is that in 2016 we still have this blending of cultures all thriving in the oldest capital city in the country.

You set up the gallery, with your partner Allison Barnett, 18 years ago: Can you tell us about your original ambition, and what your five-year plan was, at the time? How did you think opening a gallery would impact your own career as a maker?

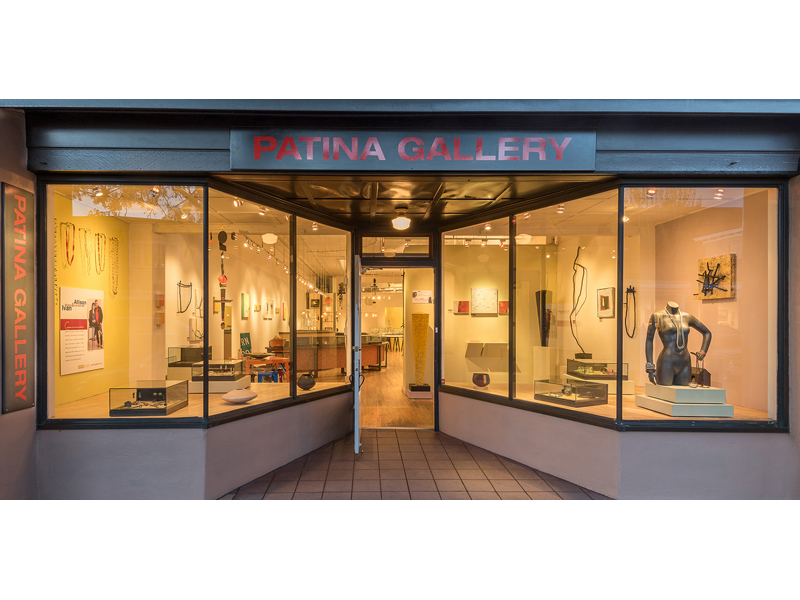

Ivan Barnett: As I write, Patina is entering its 18th year in its original space in the historic museum district of the City Different, Santa Fe. During the 1930s, what is now our gallery space was home to the Native Market, a workshop and commercial space that helped Hispanic craftsmen and their families weather tough times. The Native Market was the starting point for what has grown into the Santa Fe Spanish Market, internationally known for promoting Spanish Colonial arts.

The original five-year plan for Patina was pretty simple and direct: exhibit and represent only the best works in the field of craft and more importantly show works that we truly love and adore, works that have a voice and speak to us. Hence “soul-stirring works” became our mantra, and still is.

I had always been a studio artist. My father—a painter—and I shared a studio in Philadelphia, in the 1960s. Then I went on to have my own studios in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and then in Santa Fe. The simple answer as to how opening the gallery affected me as a maker is this: I had the luxury of being able to join Patina’s stable of makers without having to think about where to be represented.

In the early years of Patina, Allison and I collaborated on jewelry pieces for the gallery, but it quickly became apparent that the gallery had to always come first.

You represent a mix of American and European artists, working in a wide range of media (clay, wood, metal) and disciplines (jewelry, sculpture, ceramics, painting, photography): Can you let us know about the criteria that guide your selection process, and how you articulate your selection across media?

Ivan Barnett: From the beginning, Allison and I made a pact that we would always need to agree on the choices we made for the gallery. This simple pact hasn’t changed over the many years. We choose things we love and adore, pieces that we would love to add to our own collection and live with.

Love and adore: That framework allows Allison and I to move into as many directions as we like, from photography to folk art and, of course, always jewelry. We love great design, and thus we can embrace objects of all kinds. I was taught as early as the age of 10 that all great art of any scale must carry the elements of superior design, and that design was at the heart of everything, from a chair to a painting, from a bead to a fresco. Many of the artists in the gallery are world-renowned for what they make and do. Yet some are not.

A very recent example of an unexpected turn is Michael Furman, unquestionably the leading automotive photographer in the world. He does “portraits” of elegant, beautifully engineered classic cars. Furman showcases limited-edition, handcrafted works of art. It’s fitting, then, that an exhibition of his Alfa Romeos will grace Patina in honor of the biggest car event in the Southwest, the Santa Fe Concorso.

You once wrote to me about your fascination for women “engaging with the mirror” in the gallery, describing the process as one of treating the body as a canvas: What, in your mind, is the thought process of your clients as they try things on? How is the intention of the artist transformed by this process?

Ivan Barnett: In the 1990s there was a very well-known studio jewelry maker in Santa Fe named James Barker. James made incredible pieces of one-of-a-kind jewelry. He was an amazing studio goldsmith. He said that he made “pieces for women to wear and to feel beautiful and not be left in a drawer.”

That about sums it up for our Patina patrons, and I want to clarify that our patrons are high-powered executives, mothers, inventors, business owners, collectors. They are 30 to 80. As women, they have one thing in common. They want to feel beautiful and special. The ritual of women and men adorning themselves crosses all cultures and, for that matter, all times.

In 18 years, I have watched hundreds of women make the pilgrimage to the mirror. It’s almost ritualistic. They are interested not only in how a piece may feel on them but, of course, also in how it may enhance the body.

Women and men don’t come into Patina to try jewelry on so that they can feel bad about themselves! The adoring man or woman who is surprising a partner doesn’t usually acquire a piece to be stored in a drawer. We have women who wear $20,000 brooches to tie sashes around their waists.

As for the artist, it is very simple. They want to know that their works have gone to a great home and that the wearer will get joy out of wearing the piece. As soon as a prospective wearer takes ownership and adorns their body with the piece, it becomes an extension of the wearer’s personality both physically and emotionally.

In that email, you speculated about the difference between owning works of art and wearing jewelry pieces. One of the differences is that jewelry has a dynamic life: It can be tranformed by the wearer, and it can transform the wearer, continuously. Do you think that this is an apt way to describe the relationship between wearer and work? Does that make you a matchmaker?

Ivan Barnett: I love the notion of a matchmaker. It’s like an old-fashioned arranged marriage, especially when the match is made in heaven, so to speak … when a wearer and the piece of jewelry really become one.

Some contemporary jewelers—and some collectors—are happier for work to be shown on the wall—as works of art—rather than be worn by someone. As someone who represents both autonomous and wearable art, how do you feel about that?

Ivan Barnett: One thing that we never do in the gallery is pass judgment as to how the patron or the collector “feels.” They support our gallery and the artists who entrust us to represent them. “No judgments,” I say to both our staff and our patrons because, in the words of Hillary, “it takes a village”: the maker, the gallery, and then the collector. We all need one another.

Last year, around this time, you sent me some quite extravagant images of your last opening with Peter Schmid’s work: People came to the gallery in wigs and ball dresses, for a show that was dedicated to the Santa Fe Opera. You have invited Peter Schmid again this year, for a collection titled 60 Shades of Black, inspired by Don Giovanni. Can you tell me about the genesis of this ongoing project, about Schmid’s collaboration with wig and makeup artist David Zimmerman … and about the show’s overt references to sexuality?

Ivan Barnett: Theater has always been a huge part of what we do at Patina. We are in a form of show business. Lights, music, camera, action … the curtain—the gallery door—opens, and we are there to entertain and engage.

Over the last several years, the gallery has been moving toward a more interactive place. It’s somewhat a business model of a three-ring circus or, in our times, Cirque du Soleil! Bring people to Patina for a moment that cannot be replicated. This takes amazing lifting by a team of professionals. The incomparable Allison engages and serves clients brilliantly. The team also includes storytellers, world-renowned photographers, amazing events people, and me—the one who connects the dots.

The Santa Fe Opera is known around the world, with 60 years of history. In our 18 years, we have found great colleagues at the opera, just up the hill from the gallery. Two years ago, the opera called us and asked if we would lend jewels to famed mezzo-soprano Susan Graham. She needed them for a photo shoot. Before we knew it, Dallas-based hair and makeup artist David Zimmerman was standing with Susan and talking to Allison about what would work well with a certain dress. Well, the rest is history. David was so impressed with the Patina jewels, many of them by Peter Schmid, that we began a discussion over cocktails while Peter was in Santa Fe.

As to the sexual references around the 60 Shades of Black for this year’s opera event, there is no doubt that most operas are full of sexual tension. We ran our working title by our opera partners six months ago, and they loved it. The character Don Giovanni in Mozart’s opera isn’t exactly a sweetheart of a guy. He’s the ultimate narcissist in many ways. “60 Shades” seemed to fit. When I came up with the title, I was thinking of the light and dark aspects of Don Giovanni. My intention was to give Peter Schmid a jumping-off point in terms of color and theme.

David Zimmerman also loved the tie-in with Don Giovanni, which is the most elaborate opera the Santa Fe Opera had ever produced.

The collection features some impressive cuffs, all the more striking because they use a reduced palette of yellows and blacks. How long did Peter Schmid work on this project, how many pieces are you showing, and why is there a special emphasis on black?

Ivan Barnett: Peter worked on the project for the past eight months. As soon the photo shoot happened in January, the design process began for everyone. The entire show includes well over 200 works.

The emphasis on black is as much a metaphor as it is literal. Peter has always used oxidized surfaces in his pieces, and black diamonds have been part of his gemstone vocabulary over many years, so it was a natural.

On the evening of the gallery event, an actual 10-minute operatic reveal directed by David Zimmerman featured a handful of the opera performers, in the gallery in period costumes, dripping with Zobel jewels.

Some of events you organize—including the ongoing collaboration with the Santa Fe Opera—make a lot of room for the social aspect of choosing and trying on jewelry, as if jewelry were an excuse to celebrate conviviality: being together, dressing up, checking one another out. How did this aspect of running a gallery come about, and how do your clients react to it?

Ivan Barnett: Any man who’s gone with a woman while she’s on the hunt for that perfect pair of shoes will know the answer here. Jewelry, like shoes, can become an extension of the woman’s psyche. The actual process of courting—shopping—is indeed as much a part of the adornment as the final selection. One could almost say it’s a form of romance.

A woman gets to fall in love over and over again at Patina! Every woman has a different approach to the courting process. Some like privacy, and some don’t mind being in a crowded room with their peers. A woman can have an affair with a piece of amazing jewelry.

I might add that Peter Schmid is brilliant with his patrons. He is a master of engagement. The artist’s presence in the gallery affects or enhances the experience.

Can you let us know what you are reading at the moment, and what future projects are currently floating your boat?

Ivan Barnett: I’m reading a book called Utopian Vistas, by Lois Rudnick, about famed salon maker Mabel Dodge Luhan and her time in New Mexico, and the impact she had luring the likes of D. H. Lawrence and Dennis Hopper to her land of enchantment. In many ways, she put New Mexico on the tips of the tongues of the world’s artistic elites over 60 years ago.

What’s been floating my boat over the past few months is the Hamilton phenomenon around the global success of the Broadway hit. Lin-Manuel Miranda took a risk to create something that hadn’t been done before in the theater. The brilliance of this blending of history and contemporary culture is mesmerizing.

As for future projects for Patina, we are working on a collaboration with an international fashion institute and on Cuban makers, a new collaboration with the former head of cultural affairs of New Mexico, who is an expert on Cuba. I also will be presenting an idea to the Santa Fe Opera development department on a jewelry exhibition for 2017 that ties into the world premiere of its contemporary opera about Steve Jobs or the redux of Die Fledermaus. And then there will be drinks with David Zimmerman and Peter Schmid in August, … and who knows?

INDEX IMAGE: Ivan Barnett, co-owner of Patina Gallery, Santa Fe, 2015, photo courtesy Patina Gallery