Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity

May 14–September 18, 2022

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, US

At the dawn of the 20th century, the introduction of the aesthetic elements of Islamic art through exhibitions, publications, travels, and personal collections fueled new ideas and possibilities at Cartier. The Maison began to conceptualize and execute a multiplicity of designs filtered through colors, materials, shapes, and techniques. They mined artistic elements from the past, both from their own archives and from original source materials, in pursuit of modern innovation and contemporary trends. The exhibition Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity explores how diverse sources spark creativity and generate new forms of visual expression that span centuries and continents, crossing time, geography, and media. The Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) is the sole North American venue for Cartier and Islamic Art, and its co-organizer. The show features over 400 objects including pieces from Louis Cartier’s exquisite collection of Persian and Indian art and the work of the designers of the Maison Cartier from the early 20th century to the present day.

The formative influences of Islamic art on Louis Cartier as a collector and, more significantly, on Maison Cartier’s production of jewelry and precious objects from the early 20th century until today is divided into four sections. Co-organized by the DMA and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, in collaboration with the Musée du Louvre and with the support of Cartier, it offers several groupings of jewelry, objects, and archival materials alongside works of Islamic art drawn from international collections, including the Keir Collection of Islamic Art, on loan to the Dallas Museum of Art.

The exhibition starts with Paris at the dawn of the 20th century. The city was a catalyst for creativity. As European powers expanded into the Middle East, India, and North Africa, Paris became the center of trade in Islamic art and architectural elements. At the same time, the study of Islamic art was emerging as an academic discipline, with major exhibitions presenting these visual works in a more scientific, formalized manner. The origins of Islamic influence on Cartier through the cultural context of Paris in this moment is most informed by the figure of Louis J. Cartier (1875–1942), a partner and eventual director of Cartier’s Paris branch, and a collector of Islamic art. Louis encountered Islamic arts through various sources, including the major exhibitions of Islamic art in Paris in 1903 and 1912 at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which were held to inspire new forms of modern design, and a pivotal exhibition of masterpieces of Islamic art in Munich in 1910. Fascinated, he acquired many works, photographing them to share with his designers, and lent them to many exhibitions. The importance of these exhibitions, and those that followed, is two-fold. They sparked curiosity and admiration for the masterful execution of Islamic art, and they created a generation of collectors like Louis himself, who valued the importance of sharing his personal holdings with the public and his own designers.

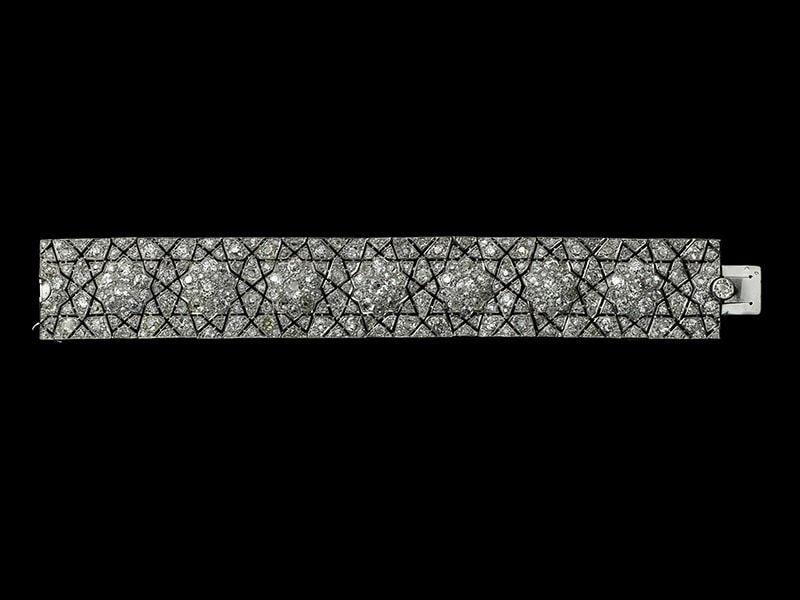

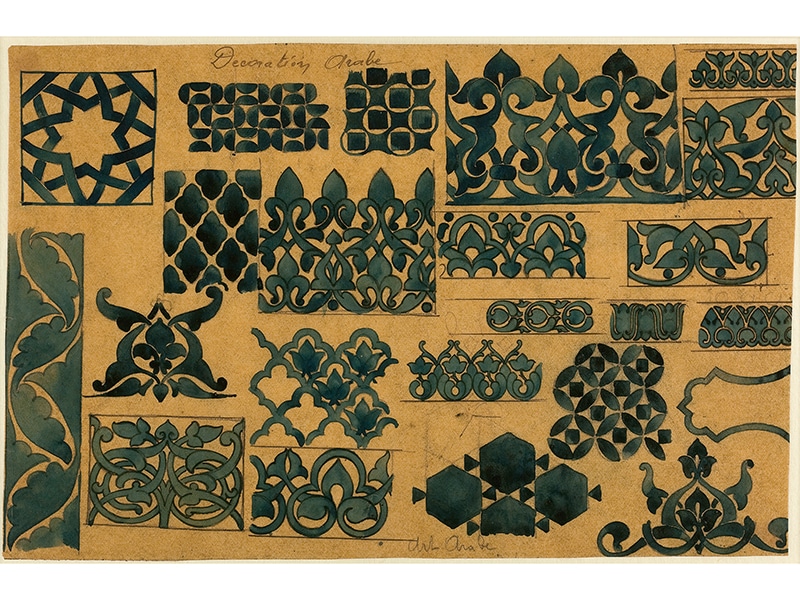

The second section of the exhibition pivots to the accumulation of sources from artworks to pattern books and how the Maison’s designs were informed by drawings from the archives of Charles Jacqueau, one of the Maison’s principal designers. The selected materials allow us to better understand the creative process, from the original idea and first studies to the final production drawing. Intense research and visual analysis revealed the potential Islamic sources for selected designs.

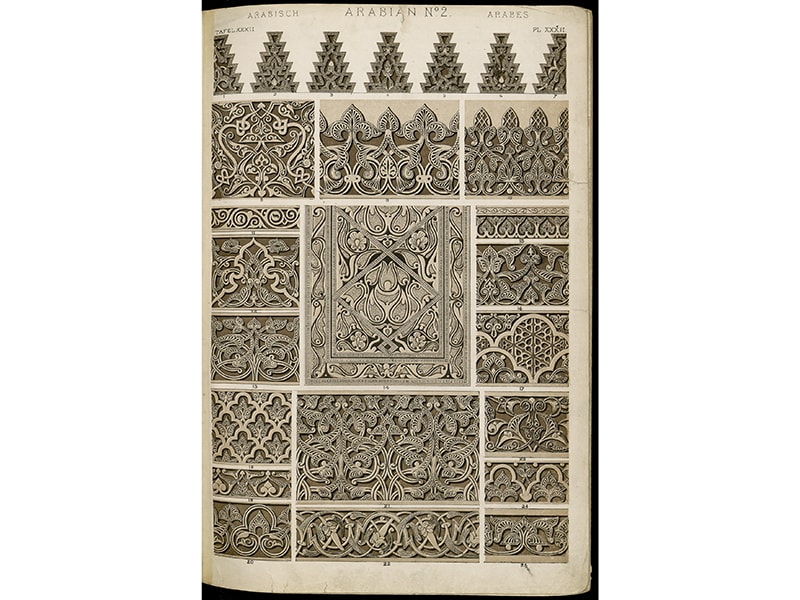

Originally assembled by Louis Cartier’s grandfather and later enriched by Louis, the study library contains anthologies of decorative ornaments, along with art history books, exhibition catalogs, and numerous publications about Islamic art and architecture. These included Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament, as well as the works of well-known French historians of design, including Adalbert de Beaumont, Eugène Collinot, and Albert Racinet.

The Islamic artwork in this section comes from Louis’s personal collection. It is difficult to date the start of Louis Cartier’s personal collection of Islamic art because he regularly purchased works on behalf of the Maison and never published his collection, which was dispersed after his death. Portions of his collection have been reunited in this exhibition, thanks to the Maison Cartier’s archives (stock books, invoices, glass plate negatives) and to the records of exhibitions to which he was a lender. He tended to favor 16th- to 17th-century manuscripts, paintings, and inlaid objects from Iran and India.

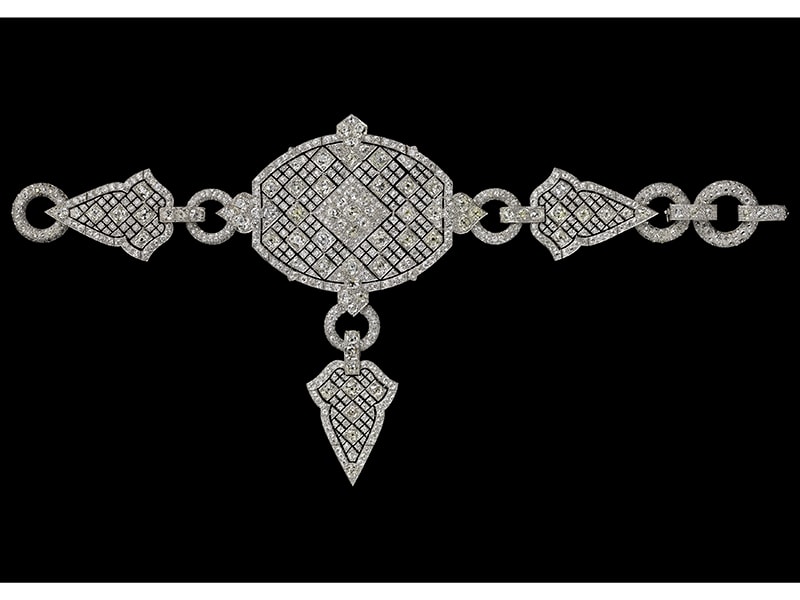

This section also explores the growing popularity of Indian jewelry in Europe in the 19th century, concurrent with British colonial rule in India. Jacques Cartier, who headed the London branch, traveled to India and Bahrain in October 1911 to meet with maharajahs, who were potential clients, and also with gemstone and pearl merchants. Upon returning from his travels, Jacques invited guests to an exhibition of “Oriental Jewels and Objets d’Art Recently Collected in India” at the Cartier boutique in London. This May 1912 event inaugurated a series of exhibitions organized by Cartier in 1912 and 1913. The London and Paris exhibition likely contained primarily Indian jewelry, but the US shows seem to have focused on modern jewelry inspired by these traditions. In so doing, the creations forecast trends that would emerge in the Art Deco jewelry of the 1920s and 30s.

The third section of the exhibition is organized around a lexicon of forms—a vocabulary without grammar rules—inspired by Islamic art. From the early 20th century through the early 1930s, under the direction of Louis Cartier Islamic architecture, manuscripts, and textiles were among the Maison’s primary sources of inspiration. These were also made available to its designers, including Jacqueau, through 19th- and early 20th-century portfolios of ornament, architecture, and photography housed in Cartier’s study library. These materials informed a number of characteristic motifs, ranging from the simple geometry of triangles to the naturalistic renderings of cypress trees.

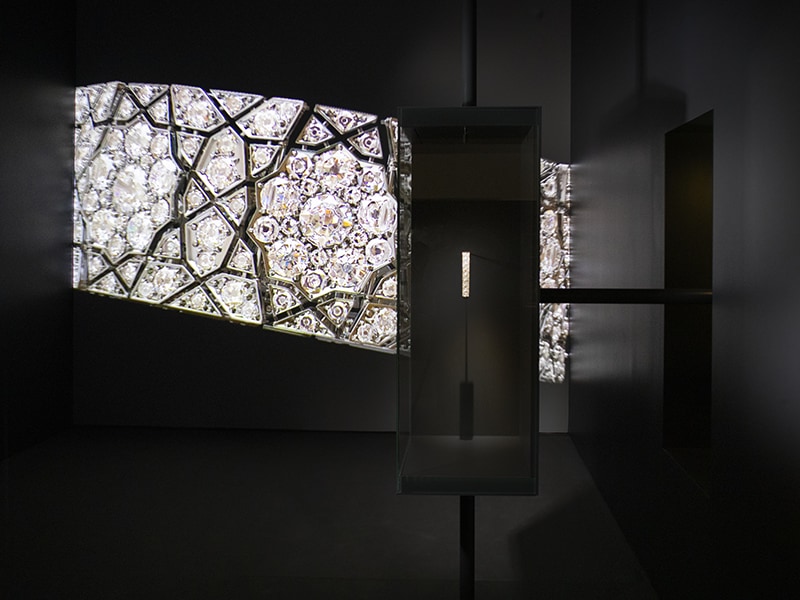

Although the objects are arranged according to individual motifs, most contain variations of multiple shapes or forms. In these various groupings, one can explore how a lexicon of forms crosses media, time, material, and function in a spectacular assembly of creative vision. Here is one of the spaces where wall-sized projections of specific works are radically enlarged to immerse exhibition attendees in the artistry and craft of the works themselves, often revealing things not readily visible to the naked eye.

The final section offers concluding examples of the ways designers integrate the influence of Islamic art and architecture. Works from India and North Africa introduced designers to new techniques and color combinations. Sometimes the workshop would not only study the forms but also create new works by revitalizing or modernizing fragments of existing jewels, objects, or textiles from India, Iran, and Morocco, among other places.

In 1933, Louis Cartier left the artistic direction of the Paris branch to Jeanne Toussaint, with whom he had worked closely for a long time. Prior to that, Toussaint had headed the S Department—S for “silver” or S for “soir”—evening. The S Department was in charge of designing practical objects that were often only lightly adorned. Until the 1970s, Toussaint followed the creative direction introduced by Louis Cartier, all the while bringing her own style and innovations. A collector of Indian jewelry, she encouraged the workshops to use all of the parts of a piece of Indian jewelry by unmounting it and remounting it with a different juxtaposition of elements. Particularly fond of jewels with a three-dimensional aspect, she had gemstones cut into beads set en masse. These became necklaces with numerous strands of mixed stones. In the 1970s, the Maison reflected the mood of the hippie movement, creating long strand necklaces and Berber-inspired pieces.

The design strategies in this exhibition—motif, pattern, color, and form—reveal the inspirations, innovations, and aesthetic wonder present in the works of the Maison Cartier. Focused through the lens of Islamic art, it reveals how the Maison migrates and manifests these styles over time, as well as how they are shaped by individual creativity. Today, Islamic art still inspires Cartier’s designers, and the Maison continues to explore innovative design arcs—an endless rotation of evolution and revolution—in its creations.

Through the lens of the Maison Cartier and Louis Cartier himself, visitors can explore sources of inspiration and the evolution of designs through September 18, 2022. While the catalog delves into the groundbreaking scholarship of the curatorial team, the DMA installation shifts focus on object looking, creating layered, overlapping moments where motif, color, form, and material are experienced through a kaleidoscope of juxtapositions. Co-curated by Sarah Schleuning, The Margot B. Perot Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the DMA; Heather Ecker, the former Marguerite S. Hoffman and Thomas W. Lentz Curator of Islamic and Medieval Art at the DMA; Évelyne Possémé, former Chief Curator of Ancient and Modern Jewelry at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris; and Judith Hénon, Curator and Deputy Director of the Department of Islamic Art at the Musée du Louvre, Paris, the curatorial narrative is enhanced by the elegant, minimalist galleries and digital media designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (NYC).