ISBN: 978-3-89790-436-1

It must be brave for an artist to author a book about their work. Writing seems ancillary to the core occupation of producing work. The act might appear self-congratulatory, unfair on the reader who cannot access, touch, much less wear the works being shown on the page, and even prescriptive in shaping audience reception as the artist is free to give full voice to their own intentions.

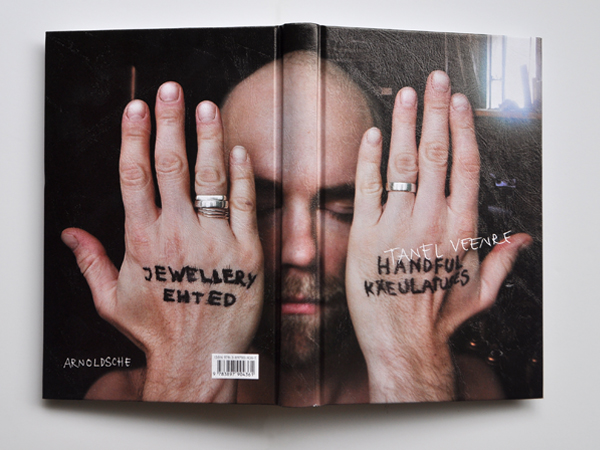

Tanel Veenre’s Handful, published by Arnoldsche this year, is billed as an artist’s diary charting the Estonian jeweler’s output between 2009 and 2015. In the foreword, Veenre admits to his “egotistical desire to expand the field of ideas; to change the world according to one’s own beliefs,” what he names the “artist’s crusade” (page 4). Although Veenre’s self-confession could be seen as an attempt to keep ego in check, it need not be seen as a problem. Grayson Perry and Tracey Emin, who are not lacking in the ego department, have written books in raw, unapologetic prose (The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl, 2006, and Strangeland, 2005, respectively), that equal the merits of their well-known work. The key criteria of judgment is whether we, as readers, want to travel with the artist-writer and his “wandering thoughts,” as Veenre puts it, or whether the content presented would have been better off remaining within the covers of the artist’s journal or notebook.

On balance I enjoyed Veenre’s journey. The writing does meander and drift off to a range of disparate topics—more on that later. But it was Veenre’s photography, the design and materiality of the book, in combination with the text, that created the initial impact. When I unwrapped the book from the packaging and flicked through the crisp pages, relishing that smell of new print, I knew I was one lucky reviewer. Next to the text-heavy, academic publications printed on miserly thin paper nearly dissolved by graying type that I usually read and review, this was a treat.

The book is a wonderful object, much like Bernhard Schobinger: The Rings of Saturn, also published by Arnoldsche, in 2014. It is case-bound with an elegant yellow and green headband. The cover is wonderfully textured and the pages are both glossy and matte, the difference in paper type marking a change in subject matter: Photographs of the studio and process tend to go on the matte pages, the finished object on the thick glossy leaves.

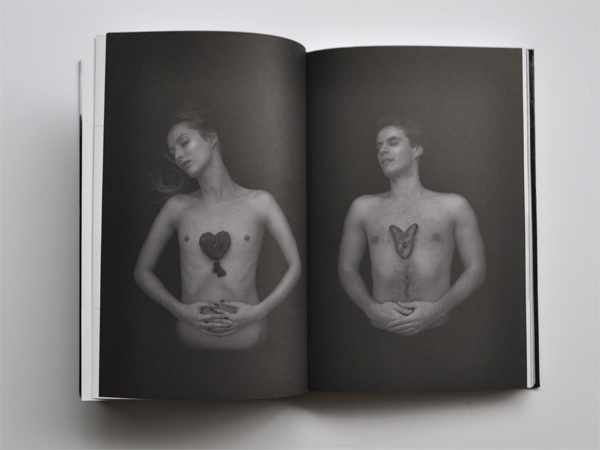

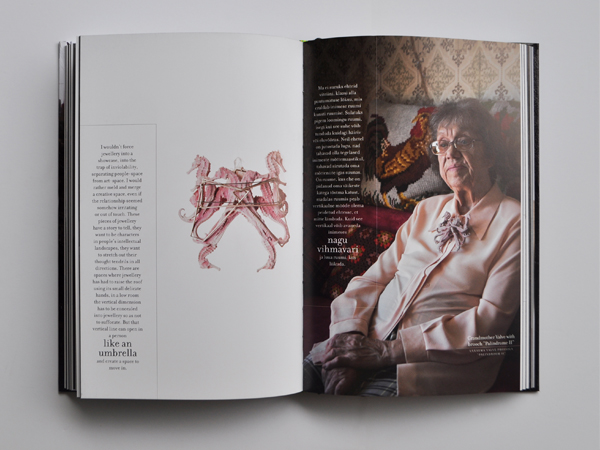

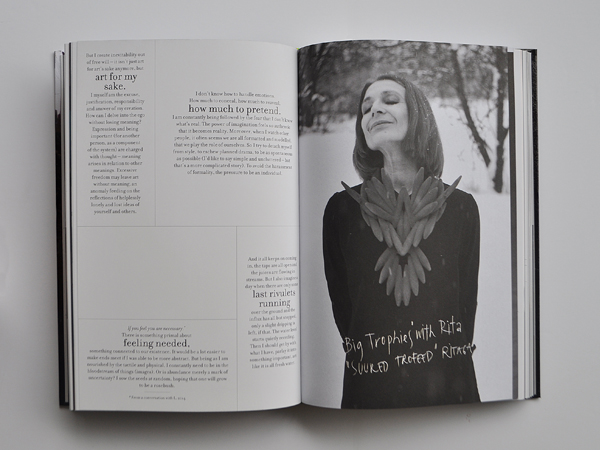

The book contains photographs of Veenre’s work taken by the artist, displayed on models, friends, in black and white Nordic landscapes and other spaces (although explicitly not in any chronological order). The full range of Veenre’s recent oeuvre is on show: from the Autoportrait as Jean-Paul Sartre (2011)—the artist bare-chested with Nausea corded around his neck—and his extensive series of seahorse palindromes (2014) to his Mutual Heart series of 2012 that sees various iterations of a heart-shaped brooch displayed in the center of his friends’ chests, the models in an array of dramatic, arresting poses. These are excellent. The designers, publishers, and Veenre-as-photographer deserve credit in reflecting the sensuality of the evocative, poetic, bodily, and crepuscular work, in book format.

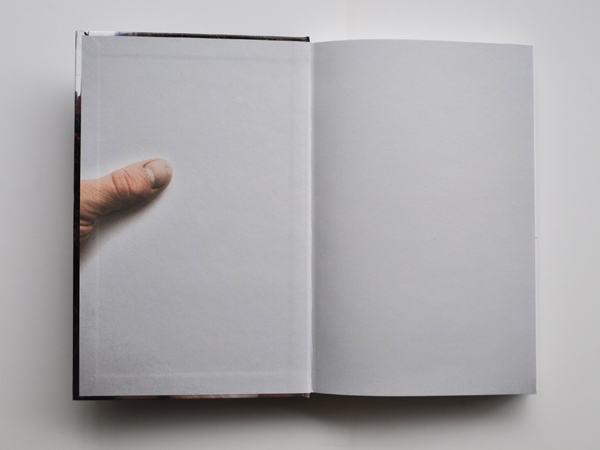

There is a clever bit of design in the book that directly responds to the title, Handful. On the inside front and back covers there are photographs of what one presumes to be Veenre’s thumbs, in the same position that the reader’s thumbs take when grasping the book. The same trompe l’œil effect appeared on a double-page spread in Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore’s seminal 1967 book The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. In both books, the tactic challenges the reader to confront the materiality of the book format and its role in disseminating the message. However, for Veenre, there is a huge physical weight between the covers; the reader is given a “real handful,” an expression in English to express something that pushes the limits of what any one person can manage or control.

Apart from the foreword, the rest of the text, in both English and Estonian, can be read in any order. This suits the book, and corresponds with the way that artists often dip in and out of literature to search for inspiration. Veenre presents his texts in fragments interspersed between the photographs of his work. He places these thoughts, aphorisms, slivers of text—none of them longer than 200 words—within the glossy white pages that have been gridded up into anywhere from two to seven boxes.

Within each fragment of text I was slightly annoyed that certain phrases or words appeared in bold—“trust-based relationship,” “made to be loved,” “transparent nothingness.” This is a tactic used by tabloids and magazines to distill the gist of a passage that in this context fettered possible interpretations of the text rather than opening them up, as I presume the artist would have hoped. More problematic was the occasional tendency toward abrupt judgments. In particular, Veenre seemed to have an axe to grind against modernist jewelry and the tendency in contemporary art to overthink things, linking modern jewelry to “the end of jewelry” (page 152), and registering a critique of art that is “smart, intolerably self-aware of its own position,” and “deliberately supercilious” (page 162).

It is clear that Veenre’s jewelry tries to tap into musky materiality, rapture, the striving for “meaninglessness” (page 220), and sensuality, among other things, all which seem an anathema to geometric modernism epitomized by Bauhaus jewelry or David Watkins’s geometric forms. Yet this dichotomy of an abstract, antisensual modernism versus a mythic symbiosis of precivilization expression that the artist is trying to tap into seems too easy. Dichotomies abound in other passages, too: Veenre categorizes all artists as inventors or discoverers (page 152)—he sides with the latter—and states that art has two “wellsprings,” that of “passion and order” (page 194). As a fellow traveler in Veenre’s journey, I found this was the moment when the tour guide barged in on the narrative, with a fair dose of prescription.

In other parts Veenre asks some very broad rhetorical questions: Early on he states, “If I turn my back on things, are they still there or do they cease to be?” (page 8); he asks himself when he will “stop flirting with the surface and actually dive into the depths” (page 48); and later on states that the “wearability of jewelry is a tricky question, any sort of conformity to external frameworks tends to water down the independence of art” (page 118). As Veenre admits in the foreword, he is not hoping for anything “conclusive” and praises the “unfinished” and “random” (page 5), but this approach meant some of the aphorisms, like those quoted above, entered the realm of dreamy speculation.

But this, I suppose, is in the book’s DNA and, countering these passages, there were many nuggets of wisdom, in particular the thoughts on the artist’s ego, desire, and the bodily nature of jewelry. For example, positioning jewelry as an “escape route” and a means of self-discovery through the adoption of different masks (page 86) seemed pertinent to Veenre’s exploration of intimacy. The artist also manages to capture the ability of jewelry to be both humble and personally liberating by analogizing jewelry to an umbrella, both of which he suggests open up and “create a space to move in” (page 164). The comparison between inspiration and inhalation (page 200) was another smart observation, as was as the comment on the “all-permissive fog of goodness,” but my favorite of Veenre’s phrases was his insistence on “art for my sake” (page 96). In this punchy riff off the old maxim of “art for art’s sake,” Veenre brings us back to his own exposition of artistic subjectivity and jewelry as a vehicle for personal expression. The passages when Veenre provides insights into his own beliefs and convictions about jewelry offer more to the reader than many of the ambulatory passages that leave too many question marks. I wanted to read more about the materiality of Veenre’s work—his use of cosmic dust, how he manipulates the seahorses—and accounts from those who have worn or own some of his pieces.

Veenre’s Handful raises the question of how to best relate the experience of the artist in book format. Do you adopt the language of expository prose and the narrative convention of biography, or do you try and communicate something of the sporadic nature of artistic creativity, with images and fragments of thought, as epitomized by the artistic journal? This book is much closer to the latter category; a good and honest reflection, you feel, of the artist’s approach to his medium and his desire to communicate. The words might occasionally leave me at a loose end, but for another reader, or when I flick through the book in the future, new resonances will surely come through.