Gijs Bakker is a well-known Dutch jeweler and the artistic director of Chi ha paura . . .? as well as various other design initiatives. Damian Skinner interviewed him on the occasion of Designers on Jewelry: Twelve years of jewelry production by Chi ha paura…? at the San Francisco Museum of Craft+Design in January 2010.

Damian Skinner: Gijs, can you explain how this exhibition is organized?

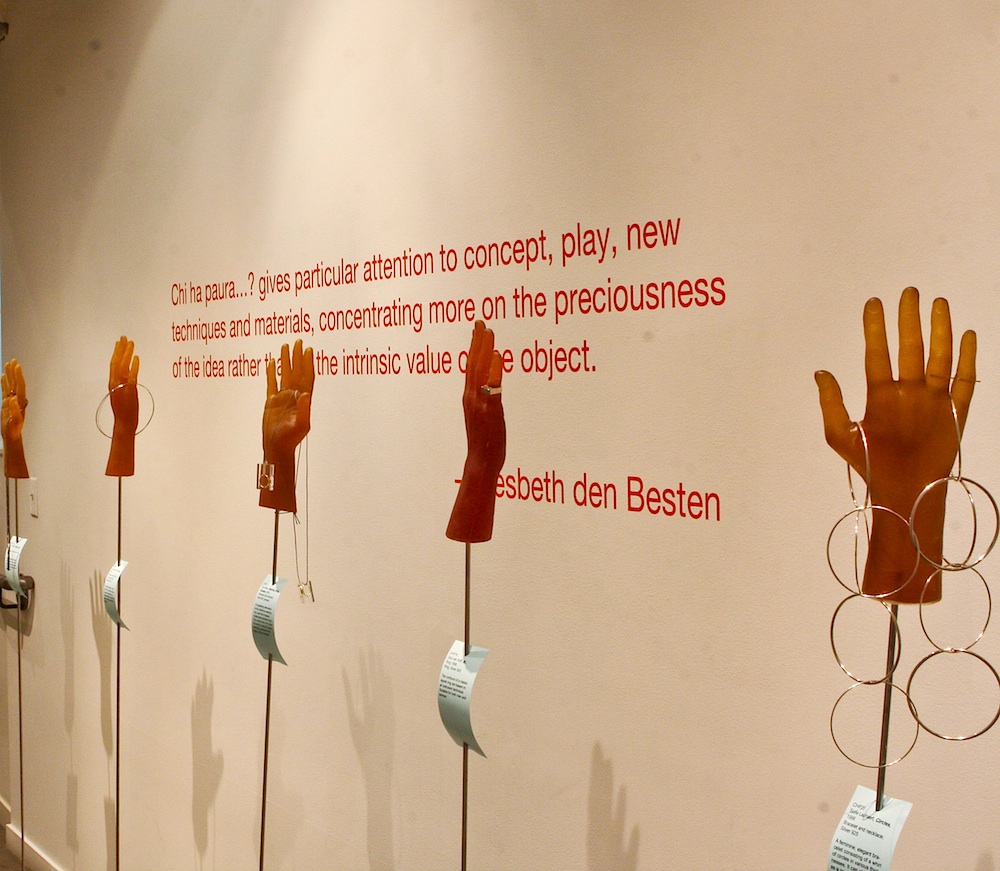

Gijs Bakker: It’s divided in four categories. The first one is the core collection, all the jewelry displayed on rubber hands. That’s the collection that was shown for the first time in Milan, Italy, during the Salone del Mobile in 1996. The second collection, Sense of Wonder, is displayed around a table. The third project is What’s Luxury? and the fourth collection is displayed in the beginning of the gallery and it is called Rituals.

It is the first collection and it is different from the other collections because they were based on a brief that I gave to the designers and invited them to work on that brief. The core collection doesn’t have a brief. Friends, colleagues like Marc Newson, in those days living in Paris, I just went there, talked with him and asked him, basically he has a background as a jewelry designer, so he made that piece. From myself, the first one is actually a plexiglass bracelet. It’s a remake – I first made it in 1968 and the idea of this Chi ha paura . . .? collection is also to have some classics to give them a longer life. Otherwise they just disappear in history. People still want to have those kinds of things, so that is mostly here in the core collection. Hannes Wettstein’s Triller Ring, for example, the idea that you can use a ring also to whistle if you get attacked or whatsoever. This is a ring out of the series Broken Lines by my late wife Emmy van Leersum. This is the only piece that I reproduced because all the other pieces are single, unique pieces so you are not going to remake those. And from Otto Kunzli, he is a jewelry designer from Germany and he had already made the idea of a gold love sign, the heart, but now for Chi ha paura . . .? he made one and named it Otto Millimetri d’Amore. His first name is Otto and in Italian it means eight millimeters of love, so this is exactly eight millimeters. All the jewelry in this collection has individual stories, whereas the other collections have stories based on the theme.

So these were pieces that came together through different networks and connections and requests that you made and they span different time periods?

Exactly. Some existed already, like the Triadic Bracelet by Charles Marks. It’s very easy to wear, nicely flexible, every hand can pass through. And the idea of the display throughout the exhibition is the original installation as it was first shown in Milan.

Exactly. As with the core collection, displayed on rubber hands in 1996. This was the first one to be done.

How did the opportunity come about to have this exhibition in San Francisco?

We had already prepared the exhibition to travel. First we would go to Australia but then the Design Centre in Melbourne went bankrupt, the beginning of the financial crisis. I was in San Francisco in February last year and I gave a lecture at the California College of the Arts here in San Francisco. One of the staff from the San Francisco Museum of Craft + Design heard my talk and he got very excited. He also knew of my other activities with Droog Design. We talked and he asked me if the show could come here. I said that would be wonderful, since we had prepared a travelling exhibition and the catalogue was ready.

Where does the exhibition go after San Francisco?

The first venue is back in Holland to the Stedelijk Museum ’s-Hertogenbosch. This will be the first time the show will be seen all together in the Netherlands. There it will be extended with a new collection, the theme of which is ‘Body Stories.’ Already fifteen designers are working on the next collection. And after that it will go to Munich, Germany.

First of all, for me, I hate to be in a jewelry shop with the glass cases, precious, hidden away. In What’s Luxury? we have precious showcases, but of course it’s a kind of irony because these are images of antique jewelry boxes from the Hermitage collection in St Petersburg. We just took them off the internet, blew them up, cut a piece out and they can function as a showcase, but that’s with irony. Here, as with the rubber hands of the core collection, the photograph of people of all ages used for Rituals and the round table with all the shirts that displays Sense of Wonder, the point is to break away from traditional jewelry. That’s also my aim with Chi ha paura . . .?, to make a bridge between the design world and the jewelry world. Because the jewelry world is a very special, limited, closed society internationally, we’re very closed and the design world has no idea that it exists. For instance, ten or fifteen years ago I went on a lecture tour in Brazil with Ron Arad and Konstantin Grcic, both of whom now have a piece in this collection. We listened to each other’s lectures and they didn’t have a clue that jewelry was my background. They knew me a designer and they knew me as the co-founder of Droog Design.

I can also put it another way. Like Ingo Maurer, I don’t know if you’re familiar with him, but he’s a fantastic lighting designer from Munich. When I asked him to design a piece for the collection of Chi ha paura . . .? he said, ‘I’m very flattered because what you guys are able to design on a little square centimeter, I’m not able to do that.’ And that was very wise, very honest, because it is of course very difficult to give content, create meaning, conceptual meaning in a small object. A piece of furniture or a cabinet is easier already, but jewelry is very concentrated, very dense. And every time I use the word jewelry in the design world people turn away, saying ‘It’s not my cup of tea.’ I want to have the audience that goes to design shops for their furniture or table top products, I want that kind of audience to be confronted with this kind of jewelry.

There’s a definite sense in which you’re disappointed by the conventional jewelry world, the world of diamonds and gold and so on. But there’s also a sense in which you’re disappointed by the contemporary jewelry world.

Yes, because that is also a very closed world in itself, where the craft, the making is highly important and my background is always that the concept is the most important part. If there is an idea, then of course it is very important how you make it. But if it is lacking in idea, if it is lacking in concept, what is left over? Nothing.

Because I give quite a lot of lectures all over the world, I’ve noticed that especially the jewelry designers in various art schools, they admire this work but it feels very difficult. They always say, ‘Oh, I could never come up with an idea like this.’ Because they work from a material starting point, material expressions and they put many materials together, all nicely hand-made. This work is much more the approach of a product designer. When I brief the designers for these themes, the brief states that the jewelry has to be reproducible, that it has to be able to be reproduced for a reasonable price.

So you don’t have a great respect for craft?

Exactly.

What would you say then to contemporary jewelers who were very interested in concept, but who also believed that craft was an important part of what they did? People who saw themselves as craftspeople as opposed to designers? Do you think they’re just banging away at a dead-end situation?

Well, if I look at the effect it has on the history of jewelry or the history of design, it’s very little. I participated myself in an exhibition in the Victoria and Albert Museum dealing with the postwar period. That was not an exhibition dealing with jewelry or architecture, no, it was about work that dealt with the issues of that period. From me they had a big aluminum necklace, not because it was jewelry but because it was a statement from 1967 that fitted in with the concept of the exhibition. The second piece of jewelry was by a Czechoslovakian, an artist called Vaclav Cigler who was very revolutionary, a thinker from the 1960s in the former East European communist situation. Actually, I don’t care much about the fact of craft or design or whatsoever because I’m a fortunate person born in the Netherlands and we don’t have this very strong tradition of craft. The interesting thing is, if you know the Dutch word for design or designing, it is ‘vormgeven,’ creating form and giving, creating with content. Fortunately, we never had this very strong idea of craft. Like in Great Britain and here in America and also Australia they have a tremendous pang toward craft.

In hindsight, the moment you came to prominence in the 1960s does look like a time of revolution, a break with what came before. What was it about that time that made it possible to re-imagine jewelry in such a radical way?

It was a period in which everything was reinvented. Life was reinvented by our generation. It could be in theatre, it could be in music, if we think of someone like John Cage for instance, in ballet and also in jewelry. So everything that was established had to be re-established after the war, especially in Europe of course, still the postwar period if we speak about the early 1960s. When I was taught at art school in the last part of the 1950s it was very traditional. The art school in Amsterdam was very traditional. I learned to be a goldsmith, make hinges, lockets – there was not any talk about concept or art, you had to learn how to make it and that was it. I had a lovely teacher but intellectually he had nothing to tell me. So when we finished at art school, in this case with my late wife, we found ourselves looking back and thinking, ‘Shit, is this it? Is this going to be our life to make luxury gold things for stupid old ladies? Come on!’ Such questions were of course embedded in a very political, social environment that was exploding. Sometimes young colleagues say to me, ‘We envy you because you started in such an interesting era.’ But now I say to my students, ‘You are lucky guys because you start your career in the midst of a financial crisis, it’s great because this is really shaking the whole world and it’s a good time to start because at least things are changing.’

So if your revolutionary goal was to change jewelry, to become part of a wave of change in society, how do you explain that contemporary jewelry is still a backwater? Did your revolution fail?

Of course! It was a disaster. It failed in such a way that only collectors and museums, they could get the jewelry very cheap because we priced those pieces not for the amount of work but according to the idea that it should be accessible for young people. Those bastards they got it for very little money.

Do you think the conditions are right for another revolution? Because Chi ha paura . . .? is obviously an attempt to create change.

What is revolution? Again, it’s finding an opening, creating an opening into a new era.

Yes and no. Actually in the 1960s the work got tremendous attention in the press, it still does. And also the jewelry that we made, those aluminum and stainless steel bracelets, were bought by people our age, so it was really a living part of our own peer group, our own society. If we went to an opening at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam you would see the girls wearing my stainless steel and aluminum bracelet – it was part of how you wanted to look. And that doesn’t happen now with Chi ha paura . . .? jewelry. That’s quite a difference. So I could say in terms of success, in the 1960s it was a stronger success than now. It’s now much harder to reach people and to get them struck by the work.

How well has the model of production, the model of design, worked for the creation of jewelry?

I think it works very well because it has limitations that force you to the edge to see how far you can go and that is what I have learned from most of my design colleagues, a very good challenge to go to the edge and see how far you can go in terms of production. For professional designers, it’s easier. Jewelry designers, jewelry makers, they suffer. For them it’s very hard to solve that part of the problem.

In her essay in the Chi ha paura . . . ? catalog Liesbeth den Besten says that the model of factory production has been replaced with a custom production model. Isn’t that cheating a little bit?

Yeah. It is, it is. Because most of the pieces – not all of them – could be really mass produced and could be a fifth of the price, but that’s where my organization doesn’t have enough financial power to invest in the whole thing.

Would there be an audience if you could get the money?

Oh yes, I think so. Maybe this will happen one day, because I can’t go on all my life. I mean at this moment I think I have to take it over to a younger generation who can continue this brand, this label. I hope at this certain moment to find a company that is already in this field that has small product, but has the market to take it over and continue.

As I was saying about the smart collectors and museum people who bought our pieces in the 1960s, they bought them for almost nothing. And of course the intention of Chi ha paura . . .? is that it will be mass-produced. Think of the Bauhaus. All of us had that intention, to make things that were accessible for a bigger audience, but the mass audience was always too late and that remains the case. If you are a good collector you need to have an eye to discover some things from the very beginning. And here are some young artists, fantastic young designers that nobody knows about, but we know about them. So collectors shouldn’t just pass by and not pay attention. And also – now I get more commercial – all of these pieces of jewelry, not all of them are in production. Every time I have to make a choice because some are too difficult or have too many problems with production or price, even the concept is too difficult. So I make a selection about what is in production. All the others are more or less one-offs and will be made to order.

Does Chi ha paura . . .? sell through contemporary jewelry galleries?

No, mostly it sells through design shops. Some museum shops stock it. And we also have the website shop. So that’s how it works.

And so your intention is to keep going?

Yes. As I said we have a new collection coming up, in June it will be ready.