Sophie Hanagarth, the recent winner of the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation Prize, just opened a much awaited retrospective of her work at CODA Museum, in Apeldoorn. (Prize winners receive a cash prize of 5000 euros, the acquisition of work for the Françoise van den Bosch collection—held by the Stedelijk Museum—a specially designed trophy, and an opportunity to do a solo show in one of Holland’s jewelry-friendly museums.) Until recently, Hanagarth enjoyed the dubious distinction of being an artist’s artist: While extremely respected by her peers—and often cited as a model of formal accomplishment and conceptual coherence—she was not as well known or popular among collectors as other artists from her generation (Hanagarth is in her mid-forties). The CODA exhibition will probably help correct that, and give her rich output the recognition it deserves.

Hanagarth’s work often represents gender-specific body details: braids, puckered lips, breasts, testicles, as well as more neutral ones like fingers and teeth. Gender is not a theme that she has emphasized in past interviews, though she does cite sensuality, and desire, as her leitmotifs. We were curious to know more, and asked French anthropologist Clotilde Lebas to meet her, and discuss some of the issues that seem to be the lodestar of her work.

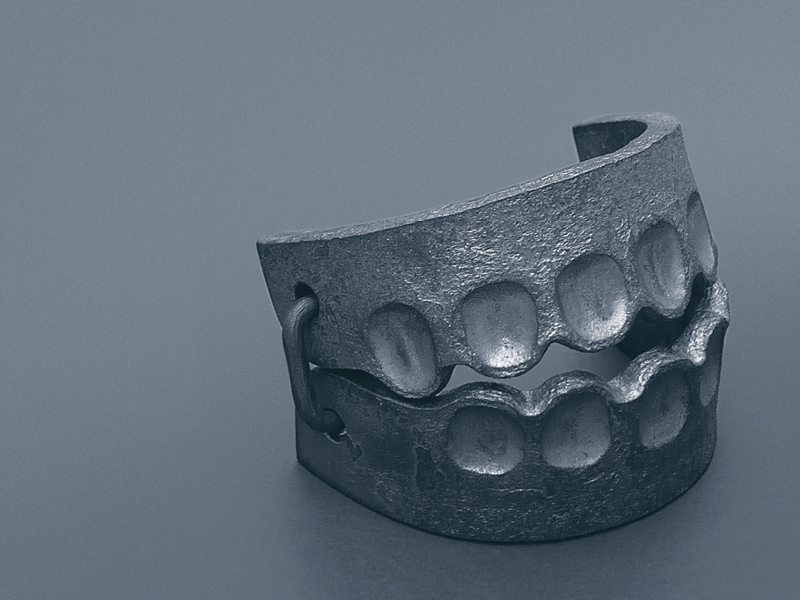

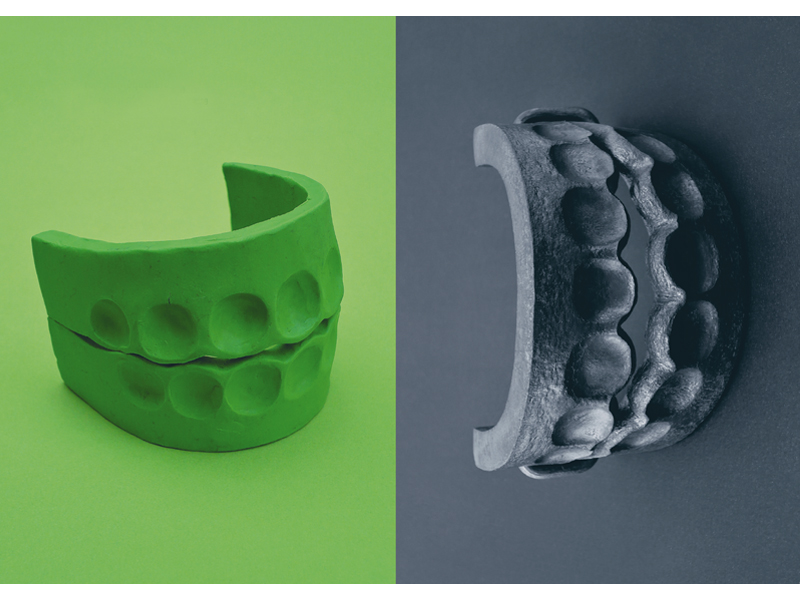

Hanagarth’s latest publication, Fers et Traquenards (Iron and Traps), features an ethnographical report on the artist’s making process, written by Brune Boyer. Accompanying the text are pictures of the plasticine mockups that Hanagarth is wont to produce on the train that takes her to Strasbourg—where she teaches—and back to Paris—where she lives and works. We reproduce some of these images in this interview

—Benjamin Lignel

Clotilde Lebas: You’ve said that you see this exhibition as retrospective. Can you explain that?

Sophie Hanagarth: The title Iron(y) is a reference to my work in iron and steel. There are also pieces in gold, but these are pieces that were primarily imagined, and above all wanted, in iron or steel.

The organization of the show is very classic, chronological. The pieces follow one after the other, always with a connection to the body. I wanted to stay close to a certain reality of the body. When you look at the rings Sixième Doigt (Sixth Finger) or Lipstick from a certain angle, for instance, you immediately see their sexual aspect. Bijoux de Famille (Family Jewels) also works like that. French Kiss is more of a “show-off” piece, not one for every day.

And, why Iron(y)? Well, I’ve been working in pure iron, especially recently, and the title suggests that my work is surrealistic and ironic—not cynical, no, but with a touch of irony, in relationship to the jewelry, to life, to pleasure. The poster is a pair of jaws with a nice set of teeth marks, Traquenard (Trap), and these jaws make one think of penis traps.

Why did you choose this piece for the poster?

Sophie Hanagarth: Well, it’s more showable than a pair of balls like Family Jewels. It seemed more significant to me, but nonetheless ambiguous—even though that’s not immediately evident. It functions as a vanity as well, like part of the skull, with a form of austerity.

So are you saying that Family Jewels isn’t showable?

Sophie Hanagarth: Well, no, but the people in charge of the show wanted to use the finger-sucking rings. For me, Lipstick is not as universal, I find the jaws a wiser choice. The Family Jewels have been seen time and time again, and they are being worn. This time, though, I didn’t want to shock, because people often think that my work is a little provocative, but that’s not the point.

So the connection between all the pieces is their relationship to the body. What are you looking for in this relationship?

Sophie Hanagarth: I believe that a piece of jewelry reactivates our body, a body that we may have a tendency to forget. Perhaps the jewelry also tends to disappear in this relationship. Maybe I am trying at the same time to hide the jewel and to deal with the body, that hidden body whose sensuality is not entirely revealed. And that’s exactly what a piece of jewelry can do; because of the fact that it is sensual. The fact that it is sonorous, that it embraces the body or collides with it. The fact, in any case, that it is tactile. In my pieces there are often moving or flexible parts. There’s always some manipulation involved. You might just do that without thinking, but this manipulation might also invite some reflection on your part. Might that not be an awakening of sensuality, the sensuality somewhat primitively connected to jewelry? I don’t know if this the right way to put it, but this jewelry acts like a target on certain parts of the body.

I am thinking of Sixth Finger. It’s flexible; it speaks about flaccid phalluses, about things we don’t see in public. There are also nipples that we can touch, or in Toison des Pattes Dorées I and II (Fleece with Golden Paws I and II) there is a contrast between the hard rabbit feet, which might suggest something phallic, and the softness of the chainmail. The Family Jewels have a body armor aspect to them. The Médailles Excréments (Shit Medals) and the rings Mises à l’Index (Put on the Index) are more about the nature of jewelry as a sign, a sign of authority. In the case of Put on the Index, the name itself is a condemnation (the French title is a play on words, which means both “putting on the index finger” and “blacklisting.” —Note from translator). The name Shit Medals evokes what you put on show when you wear medals. The Vermines (Worms) speak about our human nature, like a sort of memento mori, a reminder of death. I’ve made a soft worm, moon-shaped, like an Etruscan fibula brooch (the genre is called sanguisuga, or bloodsucker), but one that’s soft and alive. There is also a whip necklace, Q, that speaks of other forms of bodily contact (the letter “Q”, in French, is pronounced the same way as the French word for ass—Note from translator). This work calls forth ideas, sensations, like these mouths by which we might be swallowed. With French Kiss, I wondered what the tongues might represent when they are on a part of the body that doesn’t have an obvious connection to the tongue itself, and I found a relationship to hair. All of a sudden the imagination works and the tongues melt away and become the tips of hairs. And then to make the connection, I said to myself, “that’s a beautiful clasp, made by intertwined tongues.” Some readings of my pieces are mediated by the everyday, but other readings may be a bit more erotic. And above all, I think that the people who see these pieces will create their own very simple scenarios for an action.

Could you say something more about the relationship between armor and jewelry?

Sophie Hanagarth: My works are not really pieces of armor; it’s the sense that emanates from them. They aren’t meant to protect the body so much as to ward off evil. They have an apotropaic function. If you visit a military museum, the objects there have a useful function vis-à-vis the body. My pieces may seem like that, too, because they also concern the body and they are made of steel.

And what of jewelry as a sign of belonging to a certain group, or even a sign of power?

Sophie Hanagarth: Well, my pieces are really very free …

An underlying question: Who might your clients be, in your own mind? What is the point of wearing a pair of balls or a breast on some other part of the body?

Sophie Hanagarth: When I make them, I make things I would like to wear, pieces that excite me. When I wish for a particular piece, it is a very physical desire. These moments are quite rare; they don’t happen every day. The range of my pieces isn’t very large, but in the case of the rabbit, for example, I had a real desire for that piece.

A long time ago, I was used to saying that we should be conscious about what we wear. Wearing a piece of jewelry is like putting yourself on stage; it is an accessory that does not serve much else. It is also a social bond, to others. Everyone wears clothes, but jewelry is more distinctive. If you want to describe the psychology or the character of someone, take a look at the jewelry that s/he wears.

I think it is very important to be alive to what surrounds us, to what is immanent. I want to make that relationship a bit more alive. When we dress ourselves up, it is to stay alive, with our flesh, with our skin. This is also an image that I really love. It is a way of being present. This is also tied to the sound jewelry makes; it marks our presence, our being there.

If we could go back to this idea of a stage setting: What setup are you trying to create when you wear the Family Jewels?

Sophie Hanagarth: Family Jewels grew out of a tactile idea, the idea of that very soft thing. There was also the name, which is tied up with masculinity. I knew that in Italy, when men touch themselves down there, it is to ward off something bad. So it became like a game of appropriation by those who don’t have them—i.e., women. And to wear them maybe has to do with decoration, like with bunches of grapes or acorns. There might be something a little valorous there too, like military cords that end with acorns—this is all a very masculine context, the army, with ambiguous terminology. In any case, I wanted to bring something of the masculine onto women, using the accessible language of testicles.

Bringing something of the masculine onto a woman’s body?

Sophie Hanagarth: Some women might all of a sudden become autonomous, have it all. They might be autonomous in what they imagine, in what they might imagine about their progeny, for example. This is what we need!

We?

Sophie Hanagarth: Women. I don’t really know for sure, but I think that the nature of women is very tied to motherhood.

Nevertheless, one has the impression that the relationship to sex, sexuality, as well as the relationship between the sexes, runs through your work. And between sexes, between sexualities, there often are power relationships. So if a piece of jewelry can be a sign of power, what does it mean for a woman’s body to carry the family jewels?

Sophie Hanagarth: In the first part of my life, I took that for a game. Forms of power: These are things I am not used to. That’s why my work has something playful about it, though I don’t like that word very much. I am looking for a game—the game of the senses—and for a form of elegance. I love symbolists, symbols, and signs, even though it may seem a bit simplistic. So I remained faithful to the symbolists. I saw Munch’s Kiss, those bodies that melt into each other, and I took that as an ideal—the gift of one to another. I am very Swiss, it’s always half and half for me.

For French Kiss, what I was looking for was something that could evoke both homosexuality and heterosexuality, and that’s the tongue. I also told myself that it is the story of souls that get mixed together.

This then is the meaning that you give to your works. How do others see them, all these breasts, all these pairs of balls?

Sophie Hanagarth: I think that it’s very neutral.

Neutral?

Sophie Hanagarth: Yes. Each one of us can interpret a work as he or she pleases. When my dealer saw the Traps bracelets, those jaws, he couldn’t help thinking of his own penis. It hadn’t even crossed my mind. I saw much more a fist going into the body, which might be a bit cruder. I thought about one body absorbing another, about the cannibalistic idea of taking in someone else’s body.

I should also say that men are very fond of what is a bit technical, like forged iron. There are men who have bought my bracelets. My work, from a technical point of view, is not very showy, but it uses a technique I appropriated. It’s like goldsmithing, women have appropriated that know-how for themselves—just like they have done for ceramics.

An appropriated technique?

Sophie Hanagarth: At first I stamp-worked the pieces a lot. I engraved them a lot, but I am not sure that I actually imagined a masculine aspect to that, though I may have done that unconsciously. With the first pieces I forged, I found the process itself very significant, and it gave me pleasure. The fact of having hollow, light pieces in steel, and then the idea of making things that are massive, imbued with the character that forged iron can have, well, I liked that. These are things that are difficult to get into shape, but when iron is heated, it has a sort of softness. I found that aspect intriguing. And then it became a real yearning. I told myself, too, that it was a way to make things quite quickly.

While I am working on a piece, I attack the material directly, brutally, but with the right gestures so that I don’t have to clean it up by filing—though sometimes I will use the file on a piece. At the forge you have to work fast. I’m more meditative, so I take more time, but still it’s possible to make pieces quite simply. That’s what I like. When I assembled the beer bottles caps (for Family Jewels), when I soldered together all the nails, it was a job that seemed almost more feminine: a job that you repeat ad infinitum, and which gives the work a sort of amplitude. When you do that kind of repetitive work, you already have in mind what you will do next. When you are in direct contact with the material, while you are working it, maybe your thoughts are less sure. With steel or forged iron, you aren’t thinking of multiple copies. Something has changed; you have to act. Really it is a lot more reassuring to make pieces like Family Jewels, because you know exactly where you are going. When you work right on the material, there might be some surprises—a bit more, in any case. It is more dream-like. You are right in the midst of the action.

One last question: Why do you say, “I’m not a feminist,” and also, “there is nothing shocking about my work”?

Sophie Hanagarth: My work is an invitation to think about things.

Because a feminist work doesn’t invite us to think?

Sophie Hanagarth: To me, a feminist work wants to make a point. Maybe I am wrong about the meaning of the word, but I am not into staking any claim; rather, I am into proposals. And then, in any case so far, I don’t feel that I have suffered because I belong to the “other sex.”

Recently, though, I went to see a play that I really didn’t want to miss: Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto. Sarah Chaumette was in the lead role, and she is a friend of my closest friend. The text was shortened to avoid repetitions, but there are some things I found quite spot on, things regarding the role of women that made me laugh. Women have an XX gene and Solanas presents men—who have an XY gene—as though the Y were really an X with one of its branches cut off. When that makes us laugh, it is because there is something true there. The play is in crescendo. It begins very logically and ends up in total folly, with no need for men at all! It might seem a bit awful, but it was really a very joyous evening!

FRENCH VERSION

Les jouets articulés d’Iron Woman: En Conversation avec Sophie Hanagarth

Clotilde Lebas

Sophie Hanagarth, la récente lauréate du prix de la fondation Françoise van den Bosch, vient d’ouvrir une rétrospective très attendue de son travail au CODA Museum, à Apeldoorn (le prix comprend une bourse de 5000 euros, l’acquisition d’une pièce pour la collection Françoise van den Bosch – conservée au musée Stedelijk — un trophée conçu spécialement pour la lauréate, et l’opportunité d’exposer dans l’un des musées hollandais qui soutient le bijou contemporain). Jusqu’à récemment, Hanagarth avait le privilège ambiguë d’être une artiste surtout reconnue par ses pairs : très respectée – et souvent citée comme exemple d’accomplissement plastique et de rigueur conceptuelle – elle n’est pas aussi connue ou populaire parmi les collectionneurs que certains de ses contemporains (Hanagarth est née en 1968). L’exposition au CODA va probablement corriger ça, et donner à sa riche production la reconnaissance qu’elle mérite.

Le travail d’Hanagarth reproduit souvent des parties genrées du corps : tresses, lèvres pulpeuses, seins, testicules, ainsi que des parties plus neutre telles que des doigts ou des dents. Le genre n’est pourtant pas une question qu’elle développe volontiers dans ses interviews : elle préfère parler de sensualité, ou de désir. Nous étions curieux d’en savoir un peu plus, et avons demandé à l’anthropologue Clotilde Lebas de la rencontrer, et de discuter avec elle des sujets qui informent sa pratique.

La dernière publication d’Hanagarth, Fers et Traquenards, contient un rapport ethnographique sur son processus de travail écrit par Brune Boyer. Accompagnant ce texte, des photos des maquettes en plastiline que l’artiste a l’habitude de fabriquer dans le train qui la mène à Strasbourg – où elle enseigne – et la ramène à Paris – où elle travaille et habite. Nous reproduisons quelques-unes de ces images ci-dessous.

-Benjamin Lignel

Clotilde Lebas: Tu dis concevoir cette exposition comme une rétrospective. Pourrais-tu préciser ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Le titre Ironies rend compte de mon travail sur le fer et sur l’acier. Il y aura tout de même des pièces en or, mais ce sont des pièces qui ont d’abord été imaginées, et surtout désirées en fer ou en acier.

Quant au parcours de l’exposition, il très classique, chronologique. Ce sont des pièces qui se suivent les unes les autres, toujours en lien avec le corps. Je voulais être proche d’une certaine réalité du corps. Les bagues 6ème doigt ou Lipstick, quand elles sont prises selon un certain angle, on en comprend tout de suite l’aspect sexuel. Les Bijoux de Famille parlent aussi. Le French Kiss, c’est plus une pièce de parade qu’une pièce de tous les jours.

Et pourquoi Ironies? Je fais un travail, surtout dernièrement, en fer pur. Et ce titre donnait une image de mon travail surréaliste et ironique – pas cynique, non, mais avec une pointe d’ironie, par rapport au bijou, à la vie, au plaisir. L’affiche de l’expo, c’est la mâchoire Traquenard avec de beaux impacts de dents. Ce sont ces mâchoires qui font penser à des attrape-sexes.

Pourquoi cet objet ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Parce qu’il est plus montrable qu’une paire de couilles comme les Bijoux de Famille. Il me paraissait plus signifiant, avec tout de même une ambiguïté, même si elle n’est pas visible tout de suite. Il fonctionne aussi comme une vanité, comme une partie d’un crâne, avec cette espèce d’austérité.

Donc les Bijoux de Famille ne sont montrables ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Si; mais les commissaires voulaient montrer les bagues suceuses de doigts. Pour moi, Lipstick était moins universelle; je trouvais l’autre plus sage. Les Bijoux de Famille, on les a vus et revus ; et ils sont bien portés. Donc voilà, je n’avais pas envie de choquer, parce qu’on pourrait penser que j’ai un travail un peu provocant, mais ce n’est pas ça.

Le lien entre toutes les pièces, c’est donc leur rapport au corps. Que recherches-tu dans ce rapport ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Je crois que le bijou réactive notre corps, un corps qu’on a peut-être tendance à oublier. Peut-être aussi que ça dissimule le bijou. Je cherche peut-être à la fois à cacher le bijou et à traiter du corps, du corps qui est caché, qui n’est pas dévoilé dans toute sa sensualité. Et c’est bien ce que permet le bijou, qui lui est sensuel. Le fait qu’il soit sonore, qu’il épouse le corps, ou qu’il heurte le corps. En tout cas qu’il soit tactile. Dans mes pièces, il y a souvent des parties flexibles, à manipuler. Il y a toujours une manipulation à faire. On peut le faire machinalement, mais ça peut aussi inviter à la réflexion. Et est-ce que ce n’est pas pour réveiller de la sensualité ? Une sensualité liée au bijou, de manière un peu primitive. Je ne sais pas si c’est le terme, mais c’est comme une cible sur certaines parties du corps.

Je pense au Sixième Doigt, qui est flexible. Il parle de sexe mou, de choses qu’on ne voit pas en public. Il y a aussi les tétons qu’on peut toucher, ou encore ce contraste dans Toison aux pattes dorées I et II entre les pattes de lapin dures, qui pourraient faire penser à quelque chose de phallique, et la mollesse des côtes de maille. Et puis les Bijoux de Famille, il y a un côté armure. Les Médailles Excréments et les bagues Mises à l’index, ce serait plus sur la nature du bijou en tant que signe, signe autoritaire. Par la désignation – dans le cas de Mise à l’index— il y a condamnation. La Médaille Merde, c’est sur ce qu’on donne à voir, en portant des broches. Les Vermines parlent de la nature humaine, comme une sorte de memento-mori. Faire une vermine molle, en forme de lune, comme ces fibules étrusques (dite de type sanguisuga), mais une fibule molle et vivante. Il y a aussi le collier-fouet Q qui parle de ce que pourraient être les contacts corporels. Il invite à des idées, des sensations, comme ces bouches par lesquelles on peut se faire engloutir. Avec les langues (French Kiss), je me demandais ce qu’elles représentent quand elles sont sur un lieu du corps qui n’est pas très lié à la langue, et j’ai trouvé ce rapport à la chevelure. Tout à coup, l’imaginaire se fait et les langues peuvent se fondre et devenir des extrémités de cheveux. Et puis je me disais, pour faire lien, c’est un beau fermoir qui se ferme par la langue.

Ce sont des lectures à travers de l’usuel. Il y a aussi des lectures un peu plus érotiques. Et je me dis surtout que les personnes qui verront ces pièces se feront leur propre scénario, très simple, d’une action.

Tu pourrais revenir sur ce rapport entre armure et parure ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Ce ne sont pas vraiment des armures, c’est ce qui émane d’elles. Ce n’est pas pour protéger le corps, mais plutôt pour repousser le mal. Ça a donc une fonction apropotaïque. Quand on va au musée de l’armée, on a des objets qui sont dans un rapport d’utilité au corps – mes pièces pourraient ressembler à ça, car elles traitent du corps, et qu’elles sont en acier.

Et à propos du bijou comme signe d’appartenance, voire de pouvoir ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Ils sont extrêmement libres…

La question sous-jacente : à qui les destines-tu ? Quel sens cela peut-il y avoir à porter une paire de couilles ou un sein sur une toute autre partie du corps…

Sophie Hanagarth: Quand je les fais, je fais des pièces que j’aimerais porter, qui m’excitent. Quand j’ai envie d’une pièce, c’est un désir très physique. Ces moments sont assez rares. Ce n’est pas tous les jours. Le spectre de mes pièces n’est pas très large mais, pour le lapin, par exemple, j’avais un réel désir de cette pièce.

Il y a longtemps, mon propos était de dire qu’il fallait être conscient de ce qu’on portait. Porter un bijou, c’est comme se mettre en scène, car c’est un accessoire qui ne sert pas à grand chose d’autre. C’est aussi un lien social, avec les autres. On a tous des vêtements ; les bijoux sont des signes plus distinctifs. Pour caractériser la psychologie ou le caractère d’une personne, on pourrait avoir la description d’un bijou porté.

Je trouve aussi qu’il est important d’être présent à ce qui nous entoure, à ce qui est immanent; c’est par rapport à ça que j’espère mettre un peu de vivant. Quand tu t’ornes de choses, c’est pour rester vivant, avec notre carne, notre peau. C’est aussi une image que j’aime bien. C’est une manière d’être présent. Aussi par rapport à la sonorité, c’est le moment de la présence, d’être là.

Si donc on reprend cette idée de mise en scène : quelle mise en scène cherches-tu à produire quand tu portes des bijoux de famille ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Si les Bijoux de Famille ont germé, c’était dans cette idée assez tactile de cette chose molle. En plus, il y avait ce nom, lié à la masculinité. Je savais que toucher ces organes-là, chez les hommes en Italie, c’était pour repousser le mauvais sort. C’était donc comme un jeu d’appropriation pour des personnes — les femmes — qui n’en ont pas. Et de les porter, ça a peut-être à voir avec les notions de décor, comme ces grappes ou ces glands. On peut aussi y voir un côté un peu valeureux, comme ces cordages chez les militaires, qui se terminent par des glands – on est dans un domaine très masculin avec l’armée, avec des termes ambigus. En tout cas, je voulais ramener du masculin sur la femme avec ce langage assez populaire que sont les testicules.

Ramener du masculin sur un corps de femme ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Ce sont un peu des natures de femme qui pourraient tout à coup être autonomes, tout avoir. Être autonome dans ce qu’elles pourraient imaginer: dans ce qu’elles pourraient imaginer, par exemple, de leur descendance. C’est de ça qu’on a besoin !

On ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Les femmes. Je ne sais pas vraiment, mais je pense que la nature de la femme est assez liée à la maternité.

On a tout de même l’impression que la question du rapport au sexe, à la sexualité, comme celle du rapport entre les sexes traverse ton travail. Et entre les sexes et les sexualités, il y a, bien souvent, des rapports de pouvoir. Si un bijou peut être un signe de pouvoir, que signifie alors pour un corps féminin de porter des bijoux de famille ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Dans une première partie de ma vie, j’ai pris ça plutôt comme un jeu. Les formes de pouvoir; ce sont des choses auxquelles je ne suis pas habituée. C’est pour ça que mes pièces ont un aspect un peu ludique – je n’aime pas trop ce terme. Je cherche du jeu, le jeu des sens, et une forme d’élégance. J’aime bien les symbolistes, les symboles, les signes, même si ça peut paraître un peu simpliste. Je suis donc restée assez fidèle aux symbolistes. D’avoir vu le baiser de Munch, ces corps qui se fondent littéralement, m’a fait penser à un idéal, un idéal du don à l’autre. Je suis bien suisse, pour moi c’est toujours moitié/moitié. Pour le French Kiss, ce que je cherchais, c’était quelque chose évoquant à la fois l’homosexualité et l’hétérosexualité, et c’était la langue. Je me suis aussi dit que c’était une histoire d’âmes qui se mélangent.

C’est donc le sens que tu donnes à tes objets. Quel sens est donné par d’autres à tous ces seins, toutes ces paires de couilles ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Je pense que c’est très neutre.

Neutre ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Oui, chaque personne peut l’interpréter comme elle veut. Mon galeriste, en voyant les bracelets Traquenards, ces mâchoires, il n’avait pas pu s’empêcher de penser à son sexe. Ce qui ne m’avait pas traversé l’esprit. J’y voyais plus un poing qui rentre dans le corps, et qui pouvait être un peu plus trash. Je pensais plus à un corps qui en absorbe un autre, à cette notion cannibale d’absorber l’autre.

Il faut dire aussi que les hommes aiment beaucoup ce qui est un peu technique, comme le fer forgé. Il y a des hommes qui m’ont acheté ces bracelets. Mon travail, par sa technicité, ce n’est pas virtuose, mais c’est une technique appropriée. C’est comme pour l’orfèvrerie, les femmes se sont réappropriées ce savoir – comme pour la céramique aussi.

Une technique appropriée ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Dans un premier temps, j’ai beaucoup embouti des pièces, j’ai beaucoup ciselé, mais je ne suis pas sûre d’avoir visualisé un côté masculin – je le fais peut-être inconsciemment. Avec les premiers objets que j’ai forgées, j’ai trouvé le geste assez signifiant, et j’y trouvais du plaisir. Le fait d’avoir des objets creux, légers, en acier ; l’idée de pouvoir les faire de manière massive, avec le caractère que peut avoir le fer forgé, me plaisait. Ce sont des choses difficiles à mettre en forme mais quand le fer est à chaud, il a une sorte de mollesse. Je trouvais intriguant cet aspect-là. Et ensuite, ça a été une réelle envie. Je me disais aussi que c’était une manière de faire des choses assez rapidement. Dans le procédé, attaquer la matière directement, de manière brute, avec le bon geste, pour ne plus faire de rattrapage à la lime – même si je lime de temps en temps. On est obligé de travailler rapidement à la forge. Moi, je suis plus méditative, donc je prends plus de temps mais c’est possible de faire des pièces d’une manière assez simple. C’est ce qui me plaisait. Quand j’assemblais des capsules de bières, où je que soudais tous ces clous ensemble, c’était un travail presque plus féminin, du travail que tu répètes à l’infini et qui va donner une sorte d’ampleur. Quand tu fais ce travail-là, répétitif, tu as déjà à l’esprit ce que tu dois faire. Quand tu es aux prises directes de la matière, au moment où tu la fais, peut-être que la pensée est moins assurée. Avec l’acier ou le fer forgé, on n’est plus dans une esthétique du multiple. Il y a certainement eu un changement. Tu dois agir, c’est beaucoup plus rassurant de faire des objets comme les Bijoux de Famille, car tu sais exactement où tu vas. Quand tu travailles de manière directe, il peut y avoir des surprises, un peu plus en tout cas. C’est plus rêveur. On est plus dans la réalité de l’action.

Une dernière question : pourquoi préciser « je ne suis pas féministe », ou encore : « mon travail a rien de choquant » ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Mon travail est fait pour inviter à la réflexion.

Un travail féministe n’invite donc pas à la réflexion ?

Sophie Hanagarth: Pour moi, un travail féministe est revendicateur. Je me trompe peut-être sur le sens du mot mais je ne suis dans aucune revendication. Je suis plutôt dans des propositions. Et puis, de toute façon, jusqu’à présent, je n’ai pas l’impression d’avoir subi de souffrances liées au fait d’être d’un autre sexe.

Je suis cependant récemment allée voir une pièce de théâtre que je ne voulais pas manquer : le SCUM Manifesto de Valérie Solanas, interprétée par Sarah Chaumette, une amie de ma meilleure amie. Le texte a été coupé, ce qui évite les répétitions, mais il y a des choses que je trouvais assez justes, des choses qui m’ont fait rire, par rapport aux rôles des femmes. La femme a un gène XX, et Solanas présente l’homme —qui a lui un gène XY— comme un X dont on aurait coupé une branche. Quand ça fait rire, c’est qu’il y a un fond de vrai. Le spectacle est crescendo. Il commence de manière très logique et finit en une folie totale où on n’a plus besoin des hommes ! Ça semble un peu plus terrible mais, en tout cas, c’était une soirée très joyeuse !

Clotilde Lebas enseigne l’anthropologie à l’université de Nanterre.

A partir d’enquêtes de terrain menées en France et en Algérie, elle s’intéresse à la manière dont des femmes, dans des situations de rupture et d’exclusion, reconfigurent leur existence. Ses travaux questionnent ainsi les modalités de l’incorporation des assignations d’un ordre sexué. L’intention est de mettre à nu les normes qui opèrent le maintien d’un ordre sexué, mais aussi de saisir les tentatives à même de brouiller les lignes de partage entre les sexes.

Parallèlement à ses activités de recherches, elle anime des ateliers de pratique ethnologique en milieu scolaire.