This year at the International Handwerkskammer during Munich Jewelry Week, Renate Heintze was honored both as the Klassiker der Modern 2017 and with a special exhibition in Galerie Marzee’s booth. This show included her work along with that of her fellow professor Dorothea Prühl and their students at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle, East Germany, where they both taught. Because Renate died in 1991, I have asked another Renate—Renate Luckner-Bien, who knew her well—to answer some questions about her and her work.

Susan Cummins: Renate, can you tell us how you knew Renate Heintze, and for how long?

Renate Luckner-Bien: When I met Renate Heintze, she was supervising the jewelry class of the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle and I, still very young and inexperienced, had just begun my work as an artistic and scientific research associate at the department of art at that time. So we were colleagues. Renate and Dorothea Prühl were about to formulate anew the contents of the education curriculum for the jewelry class, and this against the doctrine of the East German politics of the 60s and 70s. In my position I was able to contribute to getting this new program asserted in the face of opposition from within the school. I believed that it was sustainable. I was the one who probably benefited the most from our intensive talks about all aspects of life, including those of making art. Renate and I became friends. You can therefore understand that I was deeply affected by her early death—she was only 54 when she passed away.

Did she talk about her decision to become a jeweler? Where did she study?

Renate Luckner-Bien: There was never a question of Renate becoming anything but a goldsmith. In her family, everyone was. She learned the craft in her grandfather’s jewelry workshop. She attended the vocational school, which was located in the city of Halle, 50 km away from her hometown of Naumburg. It was there that the art school came to her attention. Renate was talented as a draftsperson and well trained as a goldsmith—so she passed the aptitude test straightaway and could join the class of the metal sculptor Karl Müller. The school and her mentors turned out to be great luck for her. Müller conveyed an attitude trained on the ideal of Burg Giebichenstein and Bauhaus modernity, which combined the disciplined stylistic idiom with excellent craftsmanship.

How would you describe the kind of work Renate was known for? What were her dominant themes and most progressive ideas?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Her major concern was the image. Like many jewelry artists before and after her, she found her motifs in living nature. She loved animals. Accordingly, this manifested itself in her jewelry pieces: the hare, the cat, the bird, the goat… Her themes and formats remained “classic”. They originated in the drawing, to put it more exactly—in the line. This goes for all groups of works; the works which are more pronouncedly sculptural were still developed proceeding from the contours.

Her achievement consisted in an unconventional manner of execution as well as in the implementation of non-classical materials, such as plastic, papier-mâché, or fabric. The use of “poor“ materials in the 1970s and 1980 was groundbreaking for aspirations which, in their turn, led to the development of something that we call studio jewelry. It would have been wrong to assume that this turning to base materials was triggered by the deficit of precious metals in the GDR at that time. Renate just loved the sensual handling of materials of any kind. One thinks of the impressions her fingertips left in the wax models for casting molds or on the woven ribbons for Goldfish and Silver Grapes. Apart from that, she embraced materials on which she could work with paint.

Where would you place her in the history of German/East German contemporary jewelry?

Renate Luckner-Bien: In East Germany, Burg Giebichenstein was the only school with a jewelry class. In the closest juxtaposition with other classes of free and applied arts, the academic and artisanal training were most closely intertwined there. For jewelry, the artistic claim it made included as a matter of course its practical utilitarian purpose. To maintain the position on the international stage that is largely oriented toward the premises of free art, was a program with which the jewelry from Halle sent its own signals even as the Wall came down. The Halle jewelry school continued under the successful supervision of Dorothea Prühl from 1991 until her retirement as an emeritus professor.

When did Renate become a teacher at Burg Giebichenstein? What kind of teacher was she? How would you describe Burg Giebichenstein as a school?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Renate taught at the school from 1966 until her death in 1991. She was capable of great empathy and selflessness and had a sense of humor on top of that. With her students as well as her colleagues, she was attentive and patient, she was a good listener, and she made constant endeavors at balance and compromise.

The school has changed names over the years since 1922, but “Burg Giebichenstein” has always been part of its name because from that year onward its workshops and studios have been located on the premises of the medieval castle Giebichenstein. The school was founded in 1915 under the influence of the Deutscher Werkbund and its reform program. In the 1920s, the Burg acquired a lastingly good reputation as the most influential German art school alongside the Bauhaus. There exist interesting content-related programmatic parallels to Bauhaus, just like there exist interesting Burg-specific ways between a daring experiment and moderate modernity. Today the school perceives its history rather as a burden which is to be more or less ignored, taking into account transdisciplinary and intercultural methods, concepts, and discourses.

When Renate was teaching there, Halle was under Soviet rule. What effect did that have on the school, the teachers, and the students? After the Berlin Wall fell, in 1989, was there a change in attitude?

Renate Luckner-Bien: The reunification of Germany, which is to be imagined as a lengthy, conflict-ridden process, was first and foremost a liberation from state paternalism. It also meant the long-sought-after and now guaranteed freedom of teaching. In this connection the school applied for a long-overdue professorship for Renate. In acknowledgment of her work as an artist and as a university teacher, the Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle and the Deutsches Goldschmiedehaus Hanau mounted a comprehensive exhibition of works curated by Dorothea Prühl in 1993, which was accompanied by the first catalog published jointly by Dorothea and me.

What was the professional relationship between Renate and Dorothea? How did they share the teaching requirements? Did they both teach the same students, or did students choose to study under one or the other?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Renate and Dorothea worked together daily in the jewelry workshop of the school. The students could also observe their teachers at work and speak with them about it. Every student decided on their own who they would like to go to, and had the possibility to do so at any time and without appointment. As a rule, though, those consultations took the shape of conversations between three people at the round table of the workshop. The students heard quite different opinions at times, too. Those were, for both sides, daily exercises in reflection and discourse. Based on the temperaments in question, those conversations might also have included practical counseling in life’s problems.

A short glimpse into the works by Renate and Dorothea already shows how different their artistic concepts were. Their personalities are just as different. Their relationship was based on the common fundamental understanding of their profession, shaped by the school. The relations between both women can be imagined as a role play, with the roles finely attuned to each other and underpinned by fairness and mutual respect.

Besides making jewelry, what was Renate interested in?

Renate Luckner-Bien: For Renate, her family was important. She was a caring mother for her daughters, Anna and Lisa. Her craftsmanship and ingenuity found its use not only when making jewelry but also in the practicalities of daily life. As an example, in housebuilding. She tailored clothing for her family, too. Inspired by a friend, she took up weaving later in life. One large-scale tapestry of hers is especially moving—the one in which she, by way of an encoded autobiography, describes the various stages of her life.

AUF DEUTSCH

Susan Cummins: Renate, könnten Sie uns sagen, wie Sie Renate Heintze kannten und wie lange?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Als ich Renate Heintze kennenlernte leitete sie die Schmuckklasse der Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle und ich hatte zu dieser Zeit, noch ganz jung und unerfahren, mit meiner Arbeit als Künstlerisch-wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin im Fachbereich Kunst begonnen. Wir waren also Kolleginnen. Renate Heintze und Dorothea Prühl waren dabei, den Inhalt der Ausbildung der Schmuckklasse neu zu formulieren, und zwar entgegen der Doktrin ostdeutscher Kulturpolitik der sechziger und siebziger Jahre. In meiner Position konnte ich einen Beitrag dazu leisten, dieses neue Programm gegen schulinterne Widerstände durchzusetzen. Ich glaubte, dass es zukunftsfähig sei. Von unseren intensiven Gesprächen über alle Dinge des Lebens, die des Kunstmachens eingeschlossen, habe wahrscheinlich ich am meisten profitiert. Renate und ich wurden Freundinnen. Sie werden verstehen, dass mich ihr früher Tod – sie ist mit nur 54 Jahren gestorben – tief getroffen hat.

Hat sie denn über ihren Entschluss, eine Goldschmiedin zu werden, gesprochen? Wo hat sie studiert?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Dass Renate Goldschmiedin wurde, war gar keine Frage. In ihrer Familie sind sie alle Goldschmiede. Sie hat das Handwerk in der Schmuckwerkstatt ihres Großvaters erlernt. Die Berufsschule besuchte sie in der fünfzig Kilometer von ihrer Heimtatstadt Naumburg entfernt gelegenen Stadt Halle. Hier wurde sie auf die Kunsthochschule aufmerksam. Renate war als Zeichnerin begabt und als Goldschmiedin gut ausgebildet – so bestand sie auf Anhieb die Eignungsprüfung und wurde in die Klasse des Metallbildhauers Karl Müller aufgenommen. Die Schule und ihre Lehrer waren für sie ein großes Glück. Karl Müller vermittelte eine am Ideal der Burg- und Bauhaus-Moderne geschulte Haltung, die disziplinierte Formensprache mit handwerklichem Können verband.

Wie würden Sie die Art Arbeit, wofür Renate bekannt war, beschreiben? Was waren ihre dominanten Themen und fortschrittlichsten Ideen?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Ihr Anliegen war das Abbild. Wie viele Schmuckkünstler vor und nach ihr fand sie ihre Motive in der belebten Natur. Sie liebte Tiere. Sie hat sie in ihren Schmuckstücken gezeigt: den Hasen, die Katze, den Vogel, die Ziege … Ihre Themen und Formate bleiben „klassisch“. Sie haben ihren Ursprung in der Zeichnung, genauer gesagt in der Linie. Das gilt für alle Werkgruppen, auch die stärker plastischen Arbeiten sind immer vom Umriss her entwickelt.

Ihre Leistung besteht in der unkonventionellen Art der Ausführung sowie dem Einsatz nicht-klassischer Werkstoffe, wie Kunststoff, Papiermaché oder Textil. Die Verwendung von „armen“ Materialien wurde in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren wegweisend für Bestrebungen, aus denen sich das entwickelte, was wir heute Autorenschmuck nennen. Es wäre falsch anzunehmen, dass die Zuwendung zu unedlen Materialien durch den in der DDR zu dieser Zeit herrschenden Mangel an Edelmetallen ausgelöst wurde. Renate Heintze liebte den sinnlichen Umgang mit Materialien jeder Art. Man denke an die Abrücke ihrer Fingerkuppen auf den Wachs-Modellen für Gussformen oder an die gewebten Bänder für „Goldfisch“ und „Silbertraube“. Außerdem waren ihr Materialien willkommen, auf denen sie mit Farbe arbeiten konnte.

Wo würden Sie sie in der Geschichte des deutschen/ostdeutschen zeitgenössischen Schmuck platzieren?

Renate Luckner-Bien: In Ostdeutschland war Burg Giebichenstein die einzige Hochschule mit einer Schmuckklasse. In engster Nachbarschaft zu anderen Klassen der freien und angewandten Kunst waren hier akademische Ausbildung und handwerkliches Training aufs engste miteinander verbunden. Für den Schmuck schloss der künstlerische Anspruch mit Selbstverständlichkeit dessen praktischen Zweck ein. In einer internationalen Szene zu bestehen, die sich weitgehend an Prämissen freier Kunst orientierte, war auch nach dem Fall der Mauer ein Programm, mit dem der Schmuck aus Halle eigene Akzente setze. Diese hallesche Schmuckschule führte Dorothea Prühl ab 1991 bis zu ihrer Emeritierung erfolgreich weiter.

Wann begann Renate ihre Lehrtätigkeit an der Burg Giebichenstein? Was für eine Lehrerin war sie? Wie würden Sie Burg Giebichenstein als Schule beschreiben?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Renate Heintze hat an dieser Schule von 1966 bis zu ihrem Tod 1991 gelehrt. Sie war zu großer Empathie und Selbstlosigkeit fähig und hatte Sinn für Humor. Gegenüber ihren Studenten wie auch ihren Kollegen war sie aufmerksam und geduldig, sie konnte zuhören und war um Ausgleich bemüht.

Dieses „Burg Giebichenstein“ trägt die Schule seit 1922 in ihren wechselnden Namen, denn seit dem befinden sich ihre Werkstätten und Ateliers auf dem Gelände der mittelalterlichen Burganlage Giebichenstein. Die Schule entstand 1915 unter dem Einfluss des Deutschen Werkbundes und seines Reformprogramms. In den 1920er Jahren erwirbt sich die Burg einen nachhaltig guten Ruf als neben dem Bauhaus einflussreichste deutsche Kunstschule. Es gibt interessante inhaltlich-programmatische Parallelen zum Bauhaus, aber auch ebenso interessante eigene Wege der Burg zwischen gewagtem Experiment und gemäßigter Moderne. Heute empfindet die Hochschule ihre Geschichte eher als eine Last, die es mit Blick auf transdisziplinäre und interkulturelle Methoden, Konzepte und Diskurse mehr oder weniger zu ignorieren gilt.

Zu der Zeit, wo Renate dort lehrte, war Halle unter sowjetischer Herrschaft. Welche Auswirkung hatte diese Tatsache auf die Schule, die Lehrer und die Studierenden? Nach dem Mauerfall 1989, gab es eine Änderung in der Gesinnung?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Die deutsche Wiedervereinigung, die man sich als einen längeren, konfliktreichen Prozess vorstellen muss, war vor allem eine Befreiung von staatlicher Bevormundung. Sie bedeutete auch die ersehnte und nun verbriefte Freiheit der Lehre. In diesem Zusammenhang beantragte die Hochschule die längst fällige Professur für Renate Heintze. In Anerkennung ihrer Arbeit als Künstlerin und Hochschullehrerin zeigten das Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle und das Deutsches Goldschmiedehaus Hanau 1993 eine von Dorothea Prühl kuratierte umfangreiche Werkausstellung, zu der ein erstes, von mir gemeinsam mit Dorothea Prühl herausgebendes Katalogbuch erscheint.

Wie können Sie die berufliche Beziehung zwischen Renate und Dorothea beschreiben? Wie hatten sie die pädagogischen Anforderungen aufgeteilt? Haben die beiden die gleichen Studenten gelehrt oder haben die Studenten die Wahl zwischen Renate und Dorothea gehabt?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Renate Heintze und Dorothea Prühl arbeiteten täglich gemeinsam in der Schmuckwerkstatt der Schule. Die Studenten konnten auch ihren Lehrern bei der Arbeit zusehen und mit ihnen darüber sprechen. Jeder Student entschied selbst, zu wem er gehen wollte, und hatte dazu die Möglichkeit jederzeit und ohne Voranmeldung. In aller Regel aber waren diese Konsultationen am runden Tisch der Werkstatt Gespräche zu dritt. Der Student hörte hier mitunter auch ganz unterschiedliche Meinungen. Das waren für beide Seiten alltägliche Übungen zu Reflexion und Diskurs. Je nach Temperament schlossen diese Gespräche auch praktische Lebenshilfe ein.

Schon ein kurzer Blick auf die Arbeiten von Heintze und Prühl zeigt, wie verschiedenen ihre künstlerischen Konzepte sind. Und so unterschiedlich sind auch ihre Persönlichkeiten. Ihre Beziehung beruhte auf einer von der Schule geprägten gemeinsamen Grundauffassung zum Beruf. Das Verhältnis beider Frauen kann man sich wie ein aufeinander abgestimmtes Rollenspiel vorstellen, getragen von Fairness und gegenseitiger Achtung.

Außer Schmuckgestaltung, was waren Renates Interessen im Leben?

Renate Luckner-Bien: Für Renate Heintze war die Familie wichtig. Den Töchtern Anna und Lisa war sie eine fürsorgliche Mutter. Ihre handwerkliche Geschicklichkeit und Erfindungsgabe fand Anwendung nicht nur beim Schmuckmachen, sondern auch in den praktischen Dingen des Alltags. Zum Beispiel beim Hausbau. Sie schneiderte ihrer Familie die Kleidung. Angeregt durch eine Freundin hat sie in ihren späten Lebensjahren mit dem Weben begonnen. Besonders anrührend ist ein großformatiger Gobelin, in dem sie, einer verschlüsselten Autobiografie gleich, die verschiedenen Abschnitte ihres Lebens beschreibt.

BIO

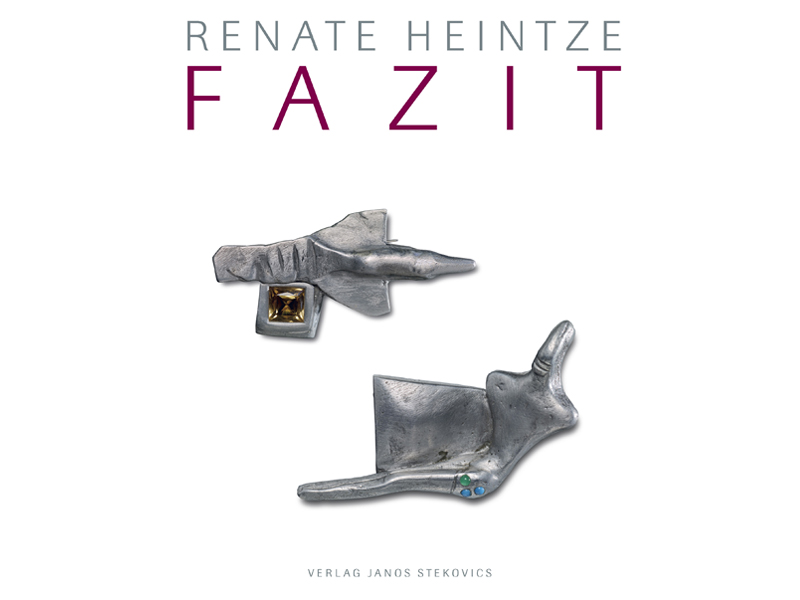

Renate Luckner-Bien lives and works as a freelance author, publisher, and curator in Halle/Saale in Germany. She studied ceramics at the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle, and subsequently aesthetics at Humboldt-Universität Berlin, and received her PhD at the Technische Universität Dresden. From 1973 to 2014, she was an artistic and scientific research associate at the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle and, starting in 1993, served as head of the department of public relations as well as being a press spokesperson. She is the co-editor of the newest monograph about the life’s work of Renate Heintze, published in 2017 by the publishing house of Janos Stekovics (ISBN 978-3-89923-375-9).

Renate Luckner-Bien lebt und arbeitet als freiberufliche Autorin, Herausgeberin und Kuratorin in Halle an der Saale in Deutschland. Sie hat an der Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle Keramik und anschließend an der Humboldt-Universität Berlin Ästhetik studiert und an der Technischen Universität Dresden promoviert. Von 1973 bis 2014 war sie Künstlerisch-wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin an der Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle und ab 1993 Leiterin der Abteilung Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Pressesprecherin. Sie ist die Mitherausgeberin der neuen Monografie über das Lebenswerk von Renate Heintze, 2017 erschienen im Verlag Janos Stekovics (ISBN 978-3-89923-375-9).

COPYRIGHT

The publication of pictures in connection with the book Renate Heintze: FAZIT is free of charge; in other contexts, the written permission of the publisher (steko@steko.net) must be obtained.

Die Veröffentlichung der Bilder ist im Zusammenhang mit dem Buch „Renate Heintze. FAZIT“ kostenfrei gestattet; in anderen Zusammenhängen ist die schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages (www.steko.net, steko@steko.net) einzuholen.

BOOK INFORMATION

Renate Heintze: FAZIT

Edited by Renate Luckner-Bien in cooperation with Margit Jäschke

With text contributions by Petra Hölscher, Margit Jäschke, Christiane Keisch, Wolfgang Lösche, and Katja Schneider, with photography by Janos Stekovics

German/English

Format: 23 x 28 cm, 96 pages, hardcover

Publishing house Janos Stekovics, Dößel, 2017, ISBN 978-3-89923-375-9

Price: €25.00

„Renate Heintze. FAZIT“

Herausgegeben von Renate Luckner-Bien in Verbindung mit Margit Jäschke

Mit Textbeiträgen von Petra Hölscher, Margit Jäschke, Christiane Keisch, Wolfgang Lösche, und Katja Schneider sowie Fotografien von Janos Stekovics

Deutsch / Englisch

Format: 23 x 28 cm, 96 Seiten, Hardcover

Verlag Janos Stekovics, Dößel 2017

ISBN 978-3-89923-375-9

Preis: 25,00 Euro