As the curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (MAMVP) since 2002, Anne Dressen is responsible for the big jewelry exhibition Medusa: Jewelry and Taboos, which runs in Paris until November 5, 2017.

Together with Benjamin Lignel and Michèle Heuzé, who were invited as advisors, she worked about three years to realize this exhibition. The idea for the exhibition stems from Dressen’s interest in peripheral and “underground” artistic practices (such as sound and copying), as well as in practices that have been marginalized in art history (such as applied arts and the decorative), and in artists who have been sidelined in official art history and by feminism, such as the Italian artist Carol Rama. She curated the exhibition Decorum: Carpets and Tapestries by Artists, which was also shown at Power Station of Art, in Shanghai (2014).

Liesbeth den Besten: Anne, can you tell us about your background?

Anne Dressen: I felt attracted to the arts for a long time, but first studied literature and comparative literature. I was interested in how fiction and writing are actually related to aesthetic and social questions; I was fascinated by Symbolism and Surrealism, and then the Nouveau Roman (a movement in literature in the 1950s) and by their connection to arts movements. In parallel, I started at l’École du Louvre (School of the Louvre), and studied art history at the Sorbonne, and also did a master’s of museum studies at New York University. Those three approaches were very different, but also very complementary one to another. My master’s thesis focused on the New York alternative space movement, or how artists invented their own spaces, outside of the problematic white cube, to show their arts in New York between the 1960s and 1980s.

You work in a museum of modern art. Why are you so interested in practices and artists that are somehow sidelined?

Anne Dressen: It was not a strategy! But I realize in retrospect that almost all my shows challenge the traditional definitions of what fine arts are. My way to question the white cube or the museum is to bring unexpected postures that deal with the fake and the copy, the commercial, and bad taste, but also the decorative, the feminist, or the queer.

I am attracted to artists’ artists—overlooked artists who are known and respected by fellow artists, but who, for many different reasons, were not shown or recognized by the institutions the way they deserve.

I am also interested in works that help queer the usual approaches. I think I am more into crafting exhibitions than in designing them. I think of exhibitions as editing, too: selecting, composing, translating, in order to make some hidden meanings emerge.

I like how artists look at things, art and objects alike; I am also attracted to works that well-known visual artists do on the side, which can be music or jewelry: the non-official facet of their works. In a way, postures that are somehow anti-authoritarian or that challenge the common or official narratives.

Can you tell us how it occurred to you to make an exhibition about jewelry? Does jewelry have a special meaning to you personally? And how did the director at the museum respond to your idea for the exhibition?

Anne Dressen: I discovered contemporary jewelry early on, because I walked past a gallery in the rue Madame on my way to high school every day. This unique workshop and gallery, called Cheret AMM, used to present Plexiglas bracelets by Catherine Noll and other contemporary jewelry in their vitrine, along with avant-garde and minimal liturgical items. But I became really fascinated by jewelry being worn from head to toe during a trip I made to India at the age of 19, which definitely changed my relationship to color, too. I love to wear jewelry, and to mix some family jewelry with vintage costume and artists’ pieces, some gold, silver, cheap metal together. I also like to wear only one earring, or two similar rings on both hands; there are some that I wear constantly, and others that I wear occasionally.

I actually thought of doing a jewelry show while working on Decorum. Anni Albers, for instance, made astonishing pieces in the 1940s, along with woven tapestries, while the Bauhaus migrated to the US (for more information on Anni Alber’s jewelry, reference this article on AJF). She was very much influenced by Amerindian traditions and used readymade and everyday objects [to make jewelry], including a strainer and some paperclips taken from the kitchen and the office, the combination of which opened brand new perspectives.

Jewelry is way more complex than what many people think. It stands between conventions, subversions, and resistance. Its spectrum is so wide, in terms of use, values, body politics; it is a performative object! It has some connection within the art world but also outside, it is an aesthetic and an anthropological object. That is what is so exciting about it. The director of MAMVP was intrigued by the proposal and soon thereafter he programmed it, as a sort of continuation of Decorum.

MAMVP, your museum, is a museum of modern art and holds no jewelry collection. This exhibition, which includes about 430 objects, must have been an immense project to organize (getting loans), design, and research. What was the role of your advisors/researchers, Benjamin Lignel and Michèle Heuzé, in this?

Anne Dressen: Actually, we do have a small but great Art Deco collection (Deprès, Boes, Templier) dating from the construction of the Palais de Tokyo for the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in 1937; back then there were many “artists decorators” exhibitions organized. But this Art Deco collection has been on permanent loan at the Galliera, the fashion museum of the city of Paris, across the street from our museum, for many years. The museum did not really pay attention [to the collection], or did not know how to exhibit it. For Medusa, these pieces have been reintegrated in the permanent collection on the ground floor of the museum, along with furniture and ceramics.

I am a contemporary art curator, which might give me some freedom to think outside the departments. Jewelry was not my specialty, but I always keep learning through researching and working on an exhibition; every exhibition is also the opportunity to constitute teams. A year and a half ago, I looked for advisors with both an historical background and an international network to collaborate with me on the show. I was very fortunate to meet two Parisian experts. Benjamin is a jeweler, theoretician, teacher, and curator; he introduced me more deeply to the contemporary jewelry world that I only knew through the collection of Mudac (Lausanne), the Musée des Art Decoratifs (Paris), the catalog of the collection of Helen Drutt, and thanks to the writings of Glenn Adamson.

Through a common collector friend, I met with Michèle, who is also very passionate; she is a gemologist, a journalist, an auctioneer, and teaches, too. Her expertise goes from prehistory to contemporary jewelry; her connections go from the Louvre to high-end jewelry houses. We were very complementary. It is very stimulating to discuss and confront, for instance, what conceptual art is from the art perspective and what conceptual jewelry is.

When I invited Benjamin and Michèle on as advisors, I already knew that I wanted to find out and address the question of why there has never been a show organized in an art museum: Why is jewelry still very much a taboo from a traditional fine art point of view? I focused on four preconceived ideas that despise jewelry as too “feminine,” too “precious,” too “corporeal,” and too “primitive.” I knew early on that I wanted to adopt a thematic angle. Thanks to Benjamin and Michèle, I could get access to many collections and artists, and also to video works. The preparation of Medusa took three years altogether; without them, it might have taken even longer, or could have ended up as quite a different show. I think that while visiting the show, one can feel that we worked really hard but that we also had a lot of pleasure. Working in a team obliges people to confront views, to test them, and to convince the others, to think further. You argue a lot, but you also laugh a lot.

The Medusa exhibition deals with jewelry of all genres, cultures, and historic periods, and you also selected some 20 fine art works (paintings, installations, video, and other media) for the exhibition. How did the concept for this exhibition develop? Are you influenced by a theoretical discourse in art history?

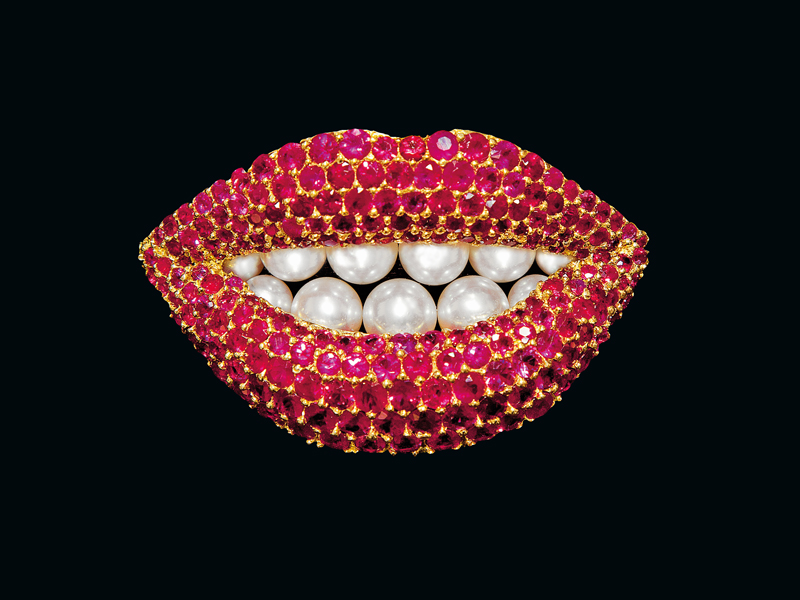

Anne Dressen: Yes, Medusa is a very transversal show. We put in dialogue different worlds, and types of jewelry which usually ignore or dismiss each other: costume and fashion jewelry together with high-end pieces; visual artists’ jewelry together with contemporary jewelry; but also ancient Western jewelry with ethnic pieces! We mixed very expensive pieces with everyday common jewelry, pop culture with conceptual postures. Medusa intends to go beyond the usual hierarchies. Altogether, Medusa confronts anonymous works (usually absent from modern and contemporary museums) and signed pieces belonging to different eras and origins, coming from prestigious museums but also personal private collections. It also seemed important to introduce–especially in France, where applied arts and design are still largely sidelined and unknown, in comparison to fine art and jewelry—some of the best contemporary jewelers.

So, it is a transversal show, but also a trans historical one: I never wanted to attempt to write any kind of linear history of jewelry, which is somehow impossible, and/or uninteresting. Instead, it was crucial to state that jewelry is a universal artistic—but also social—form of expression. While looking at a piece, it is sometimes hard to know from which period or culture it is! Some pieces look like they were done now, others look way more ancient than they actually are.

I guess this show participates in the current rewriting of modernist art history in the light of the importance of decorative and applied arts for the invention of abstraction. It is remarkable that some recent shows focus on the work of Sonia Delaunay, Anni Albers, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, who were for a long time considered as secondary figures, spouses of great artists, but whose roles in the design of patterns, fashion, and theater is only being rediscovered now, at a time where there is also a current movement that we can call “neo craft” or “post medium” emerging among contemporary artists. And this is only the beginning. For me, it follows the attempt of Deterritorialization that Guattari and Deleuze conceptualized and defended in 1972. It is also in the continuity of utopian ideas that led to the foundation of new kinds of transversal museums like the Centre Georges Pompidou, which aim to go beyond the established categories, willing to reconciliate art and life.

By exhibiting fine art in the context of a jewelry exhibition, the reading of it changes. It might be hindered or even subverted. Today, museums tend to make jewelry (and other crafts) part of so-called integrated presentations. The risk of a piece of jewelry or a pot in such an environment is that it becomes illustrative. In Medusa you changed these roles. Is this something you wanted to investigate?

Anne Dressen: I usually work with artists for the display of my shows. But for Medusa, I was convinced that we should include contemporary artworks. I wanted to complexify our reading of the jewelry but also to shed a different light on contemporary art pieces that are taken for granted as art in a mostly undiscussed way. Exhibited within a jewelry exhibition (and not the opposite), I thought that the juxtaposition could create interesting tensions and raise questions. In Medusa, the “art pieces” represent a minority in terms of number of pieces, even if most of those pieces are bigger than jewelry in terms of size and scale. I chose some pieces that evoke jewelry because of their material or, more conceptually, in terms of their decorativeness or adornment’s dimensions.

A painted mirror by Nick Mauss, a glitter painting by John Armleder, and an abstract neon chandelier by Mai-Thu Perret welcome visitors in the first rooms. In another room, I associated the first self-portrait ever taken by artist Juliana Huxtable next to a self-portrait by Michel Journiac: They are two generations of queer artists challenging gender constructions using jewelry as a feminine marker but also defending the ideal of fluidity in the definitions of identity. I also included more historical paintings or other conceptual works or documentary images that can help us reflect on jewelry: Salomé by Gustave Moreau, an amazing representation of tattooed jewelry, and on the same wall an obscure painting of a general fully covered with military decorations. It was also crucial to have many images of jewelry being worn, from Liz Taylor to Ice-T and Boy George, but also Madeleine Albright, Wonder Woman, and Nancy Cunard. Those images tend to fill a gap, to balance the absence of the body in any museum but also to reassert the role of the wearer as far as jewelry is concerned.

This confrontation between objects, images, and art also forces the eye to stay alert, constantly changing scales and supports. For me, to integrate is not to assimilate or to level one to the other, but to keep a dialogue and respect specificities. It also has a double intention to address and challenge the jewelry public and the art public, to offer a chance to revise everyone’s reflexes and habits. I invite viewers to get lost in their certainties, to see similarities but also to question the differences between applied and fine arts. Those contemporary works contribute to throwing a contemporary eye on the jewelry while the jewelry invites us to look at those art works with a more sociological state of mind.

What is the story behind the title of the exhibition? Why “Medusa” in the first place? How does it refer to feminist interpretations of Medusa? And what are the taboos?

Anne Dressen: “Medusa” is a very charged myth. It directly refers to the mythological face of Medusa, one of the three Gorgons, which embodies a power of attraction/repulsion and that is for me comparable to the effect that jewelry has on the art milieu! I do not know if this is odd, funny, or logical, but the Medusa face was very often used as a jewelry motif, and not only by Versace! Her face represents a certain danger: Medusa, like jewelry, can paralyze, make you “blind”—to quote [the title of] a great piece by Otto Künzli—or maybe make you speechless, if you dare stare at her. At least in the fantasy that Medusa carries on.

But for me, the interesting thing is that Medusa also embodies the power of the wearer of jewelry: like an evil eye that looks back and affects the viewer! That has a significance that goes beyond the simple seduction effect. So, the petrification’s threat relates to jewelry and the power of the gaze in general. For me, the Medusa myth is highly interesting because it both carries on the cliché of the femme fatale from a phallocentric point of view, of the hysterical, castrating woman that Freud or Jean Clair depicted; but it is even more interesting that some feminists, like Hélène Cixous, revisited it as the incarnation of women’s power, celebrating the free Medusa laughing. It includes many taboos all at the same time.

Artists’ jewelry is a substantial part of the exhibition. How does artists’ jewelry connect with contemporary jewelry?

Anne Dressen: Artists’ jewelry gave me the idea of the show in the first place, but it was clear that it should not get restricted to it. It is actually amazing the number of artists who made jewelry on the side, as a hobby or as one shot. Calder is an exception, as he made each one of his jewelry pieces himself all his life. The majority of visual artists collaborate with a goldsmith, delegating the making to a professional (like Hugo or Montebello); and only a few artists take this delegation aspect to make conceptual pieces.

There are many reasons why an artist would do jewelry. It can be because of the taboo it represents, the relation to the body it implies, the market opportunity that an exclusive or a multiple piece opens, but also because of the way jewelry actually promises to diffuse an art work: way broader than a fixed sculpture that does not move around.

But I do not think that every artist’s jewelry is equally interesting. Some of them work as jewelry pieces; others do not, and remain just attempts at wearable sculptures! Artist’s jewelry is actually often dismissed by contemporary jewelry as uninteresting miniaturized and derivate products, like shrunken versions of bigger and pre-existing sculptures. Some are convincing, others aren’t, in the same way that some artworks are and others are not. But what I like is that artists’ jewelry challenges the preconceived idea of an artwork which is supposed to be autonomous, self-standing, abstracted from the body.

Did you ever expect this exhibition to become so big, so encompassing, and such a demanding project? Is jewelry different from, say, tapestry?

Anne Dressen: For the tapestry show, the artist Marc-Camille Chaimowicz and I collaborated within the given white cube of the museum. I asked him to create some wallpapers, to choose some colors for the walls where the tapestries would be hung, and to design some asymmetrical pedestals for the carpets. Thanks to him, the tapestries looked like woven paintings and the carpets looked like sculptures in a sort of fictional domestic interior. But nothing was literal; we created some atmospheres, working like suggestions.

For Medusa, the selection of the pieces was of course very exciting and required a long process; we had to choose them first, and then localize them, obtain their loans, and decide which juxtaposition we wanted to make. We aimed to create some tensions, some surprises, and sometimes some funny encounters; some are even pretty subversive! But even then, the work was only half done. The next big challenge was to exhibit and secure small (and tempting) objects and therefore to work with vitrines—and my fear was that it would get monotonous. I did not want to reproduce some very conventional and codified ways of presenting jewelry like, for instance, the obscure dramatic presentation that we find in most decorative art museums. I really wanted to reflect on different types of vitrines, the way they alter our appreciation of the objects: No display is ever neutral!

We worked with a scenography agency called Projectiles, used to present ethnic or fashion artifacts (they did scenography for some of the Quai Branly museum’s ethnic art exhibitions, and also for the Jean-Paul Gaultier exhibition). We asked them to make some proposals for each thematic section of the show with specific display types. Each chapter of the show had to have its own vitrines: “table” showcases for the Identity section, “safe” showcases for the Value section, mannequin options for the Body section, and dark “column” vitrines for the Ritual section. The other challenge was to deal with the reality of the eradication of any reference to the body in a museum. The risk is always to turn jewelry into a sculpture and an abstract, nonfunctional shape. So we carefully used some mannequins, and sometimes hung some jewelry next to them at the level where every piece is supposed to be carried on the body.

The choice of presentation was therefore a time-demanding and crucial part of the preparation of the show. But what I did not expect was also all the decisions we had to make regarding the soclage (French for basing) of every individual piece. We worked with a very professional team called Version Bronze. Almost every device was custom made. Some were intended to simulate and suggest the invisible body underneath, others to focus on the sculptural dimension of the piece when not worn.

Parallel to that, the catalog was also a full-time project, as we did not want it to only reflect the exhibition’s structure, but to open the reflection even further. We asked more than 30 writers—philosophers, sociologists, theoreticians, historians, and artists—to write short essays on transversal themes as various as “the loss,” “the safety pin,” or jewelry as “control.” It was an ambitious project in its own right, aimed at surviving the show to live its own life once Medusa has closed.

What is the next project you are working on?

Anne Dressen: I just started to work again on a painting exhibition project, together with Jean-Philippe Antoine. It will exclusively focus on paintings of “bricks,” from Magritte to Kelley Walker. The bricks’ representation is a blurry space between hyperrealism and grid abstraction: It therefore questions painting itself. I am also just starting to think about a ceramic exhibition, as a sort of third chapter following Decorum and Medusa. Everything is still open. Who knows yet where it is going to be, and with whom. It is interesting to see that some jewelers also made ceramics or that ceramists did jewelry, like Daniel Kruger or Sylvie Auvray. I also recently met Betty Woodman in her studio in Tuscany. She creates a body of work that mixes painting, ceramics, sculptures, and even carpets. I like how she incorporates decorativeness in her work and challenges the bi- and the tridimensionality.

Have you recently seen or read anything stimulating? Could you share those with us?

Anne Dressen: I just bought the book Queeriser l’Art, by Jean-Claude Moineau, who used to be an inspiring teacher at Sorbonne Paris 8 university. It was just published by Les Presses du Réel, one of the best publishing houses in France. The title totally matches what I am interested in: showing art and objects from a different perspective to make us think of what they are, and how they can be looked at differently, beyond any binary categories.