Margherita Potenza: Tell us about your elm seeds collection, which was recently exhibited in a solo show at Galerie Rob Koudijs. It’s interesting to hear that you wanted to work in relationship with the city of Amsterdam by making a connection between objects, materials, and the place they come from.

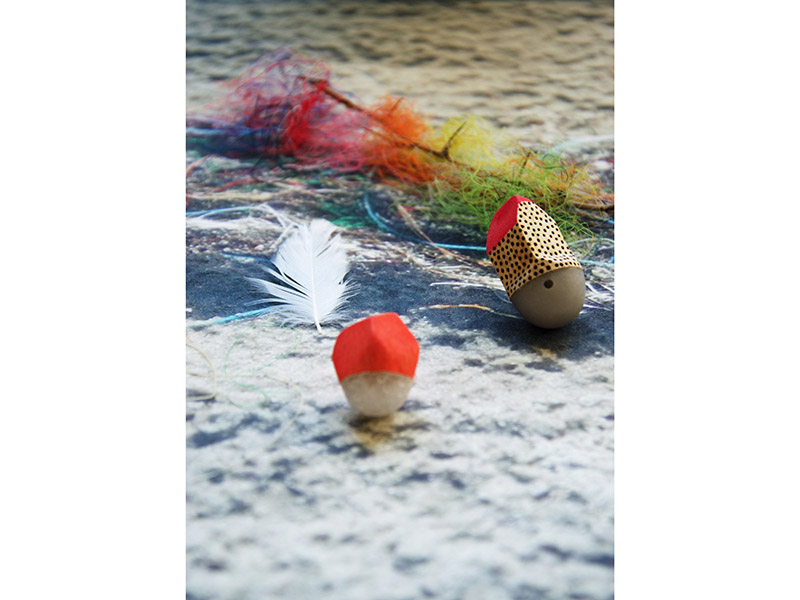

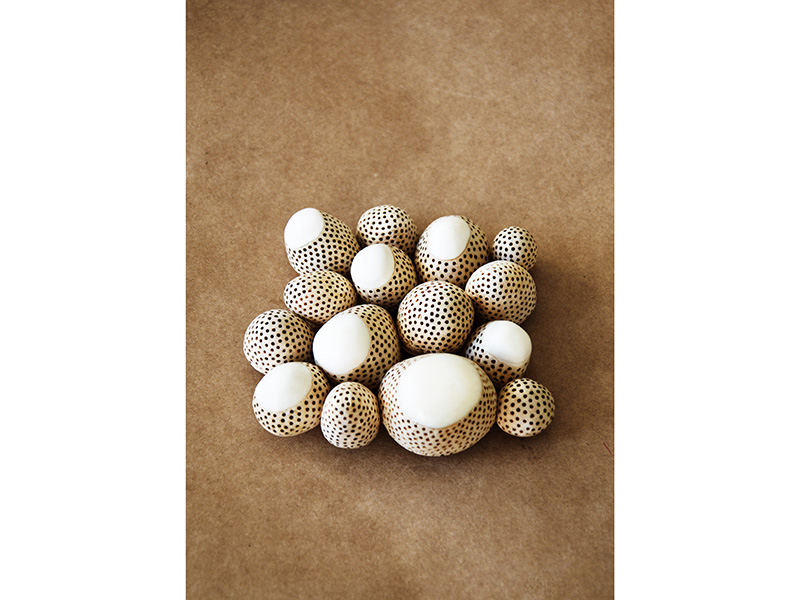

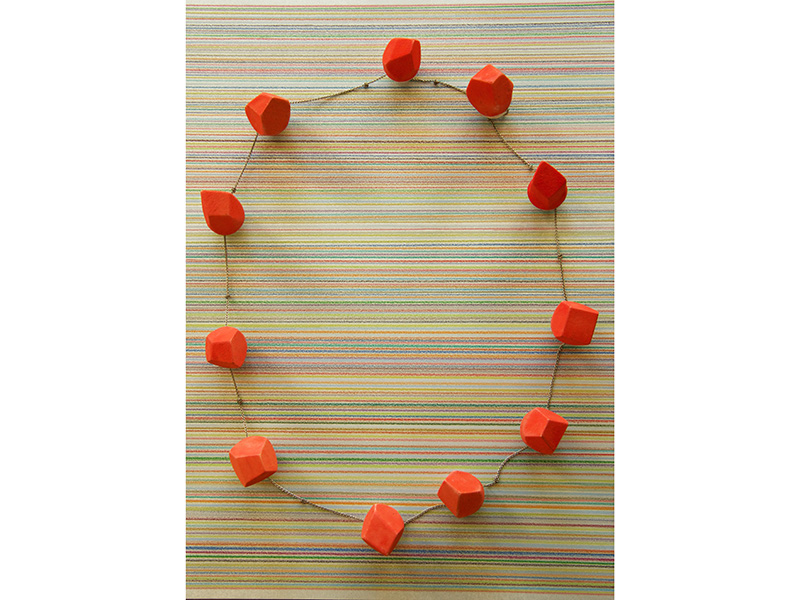

Beppe Kessler: This project started because I was interested in exploring the concept of nothing—of what is nothing. I started two years ago, working with pieces of jewelry made out of little threads, small bits of fabric, little “nothings,” so to say. These pieces carry the idea that behind the “nothingness” stands a whole dimension of memories, and this is what makes them precious. I like the contradiction that something that is practically nothing can contain everything. With time I also moved on to other materials, such as pieces of paintings, jewelry, or bits of old computers, which I used to create new compositions. For my project with elm seeds (lentesneeuw, spring snow), I was inspired by a scene of elm seeds swirling on the pavement, carried by the wind. I made a short film about it, which was exhibited alongside the jewelry collection. Looking back at them, one could also read these images as a visualization of the wind, which is also a recurring theme in my paintings.

Related: Textile-Based Jewelry by Sabina Tiemroth

Related: Review of CODA’s De Keerzijde Exhibit

Related: AJF’s 2014 Interview with Beppe Kessler

Another important exhibition is taking place this autumn as the CODA Museum hosts a large retrospective of your work through March 1, 2020.

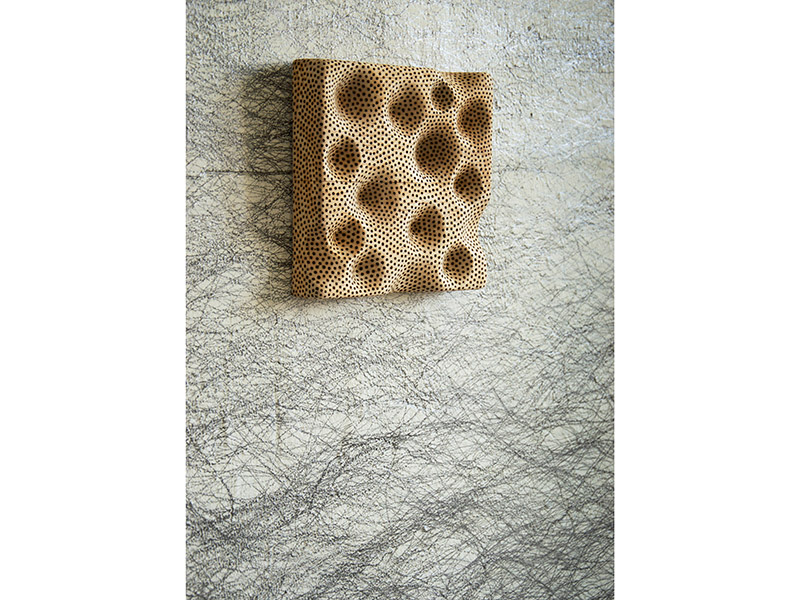

Beppe Kessler: The exhibition a time of seeing shows the development of my practice in painting and jewelry over the past 40 years. If I were to describe myself as an artist, I would say that I’m a painter who makes small things and a jewelry maker who paints. Painting and “making small things” are, to me, very closely interrelated practices: The jewelry emerges from the painting, and the other way around. Both the paintings and the jewelry reflect my thoughts and feelings on life. The exhibition shows fragments in time—a selection of works in which the relationship between jewelry and painting is most clearly visible. Although separated in their final form, they belong together, as they stem from the same soil. The themes I touch with my pieces usually emerge from the invisible, the non-substantial: wind, time, warmth, nothing. What is time, what is nothing? Throughout my career, I’ve tried to answer these questions in the shape of a painting, a drawing, a brooch.

You first started working as a textile designer and then moved on to painting and jewelry making.

Beppe Kessler: I have an education in textile design, but drawing has also always been part of my practice, so these two elements have been tied together since the beginning. Jewelry came into the frame in the 80s, when I started making rubber band pieces. That was a time when a lot of jewelry artists were playing with new, unconventional materials, so my work fit well with that context. I carried on exploring jewelry, still using textiles, and by the end of the 90s I decided I would leave textile design behind and follow my path by making jewelry that would resonate with my paintings.

A series of paintings you made last year comes to my mind, where a piece of the canvas could be detached and worn as a brooch.

Beppe Kessler: That’s a good example of how I follow my intuition, to make jewelry and painting cross in my practice. I was working on these paintings and I thought it would be beautiful to cut a hole in them and use that part as an adornment.

This ambiguity between flatness and volume is something that seems to frequently appear in your work. Another piece is a holed painting that could be turned into a collar by wearing it around the neck.

Beppe Kessler: It’s a constant in my practice to jump back and forth between the two. The paintings and drawings are necessary for me to step back from the nitpicking of making small pieces. It allows me to be in a freer mindset, and that’s when I’m tempted to go back to jewelry-making again. It’s a repeating cycle between these two fields.

You often define yourself as a “material girl,” speaking of your approach to making. What are your materials of choice? Have you still worked with textiles recently?

Beppe Kessler: I don’t work with fabrics in terms of textile design, but in a way it’s a material that I’m still very close to. There’s a series of paintings where I covered the canvases in fabric threads and then painted the whole thing in white. I then used this surface to draw with a pencil, and the fabric texture created a barrier that completely changes the trait of the pencil. I like to make up this kind of obstacle to provoke an unexpected element in my work.

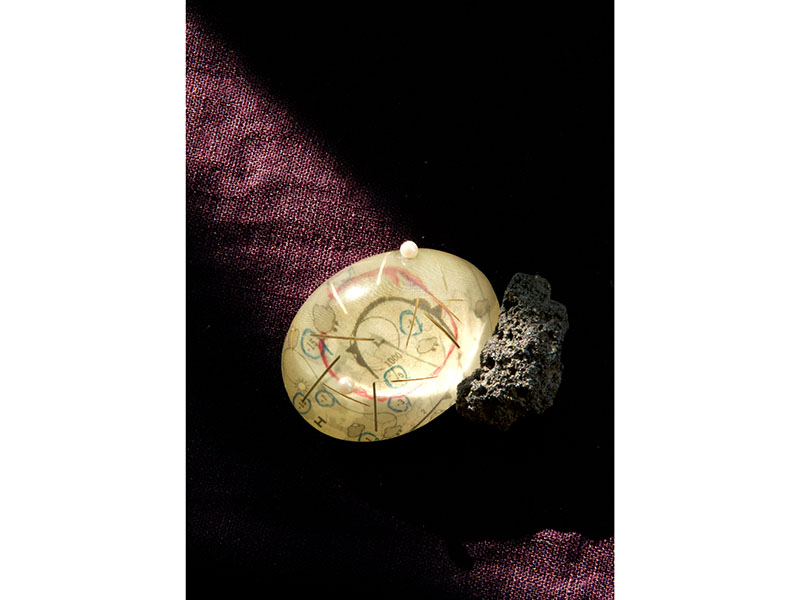

Acrylic also seems to be a recurring material in your pieces. For example, in the elm seeds collection, acrylic is used to turn the fragile, perishable petals into something resistant and durable.

Beppe Kessler: Sometimes the materials I use are very frail, so using acrylic as a cover creates both a protection and a distance, because the original tactile aspect of a material is silenced by the acrylic. To counterbalance this effect, I often use fabric, which brings back an element of touch to the piece. Acrylic is not my favored material, but what I do find intriguing in using it is that it can be shaped into a magnifying glass, which gives importance to the material underneath.

What about metal? You always create your works without soldering.

Beppe Kessler: I never learned to solder, and if I did that would open a completely new chapter in my work. I’m afraid that would make me follow a more traditional jewelry path, which I’m not interested in. It’s a challenge to work without soldering, and I’m attracted by the idea of having to work around limitations and being creative to find alternative solutions. This way I can forge my own methods. Otherwise, I use metal in my painting, where I use aluminum plates as canvases and work the surface with etching pens. In a way, these are the counterpart of the “bowed” paintings (which are often considered my signature pieces), as the aluminum ones explore flatness instead. I developed a series of “flat” works, where I first started using wooden plates to draw on, then aluminum, and finally just the wall.

Do you see nature as a relevant theme in your work?

Beppe Kessler: I wouldn’t say nature specifically is the theme I explore. I’m more concerned with things that can’t be grasped or explained visually, and many of these things are connected to nature—streaming water, the weather, wind. I look for subjects that can’t be expressed with a plain image, things that are rather made of movement, light, time. I made a jewelry collection called Ocean of Time and with these kinds of subjects you could go on experimenting for years, they’re so vast. What matters most to me is not to make something that can be deciphered at a glance—I would never paint a landscape, for example. That’s why I would say I’m not a “nature artist,” rather I’m interested in philosophy and whatever I can add to this with my practice.

I found a quote in which you say that imperfection and mistakes are a source of inspiration for you. Considering that this is a critical subject in the contemporary jewelry discourse—to the point that it became almost a cliché for art jewelry to celebrate imperfection—could you tell us more?

Beppe Kessler: I do think that mistakes can be a great source of inspiration, as they show you a path you hadn’t thought of. A good suggestion is to never throw mistakes and failed attempts away, because they can give you an unexpected perspective and take you to new places in your practice. Whenever we’re making we always have a “third eye” looking at what we’re doing. That’s why I keep a puppet high up on the wall of my workshop. It represents this idea we have about what we should or should not do, and it’s very important for me to always question this status quo of dos and don’ts. This is how I came to turn mistakes into a theme of itself, especially in my drawings: Whenever I make a mistake at drawing, I paint over it, or tape over it, so that instead of deleting it, it becomes a turning point. I think mistakes have a peculiar beauty, and if you follow them through they become something new. They’re an expression of our own intuition, our own handwriting, which plays against the rules of technical knowledge, against the “proper way.” This concept of one’s own manual language is something I try to teach in my workshops, as I think students are sometimes overloaded with rules and preconceptions of right and wrong. Everyone has to find their own criteria, and that’s where it gets interesting.

Are you still teaching?

Beppe Kessler: Yes, I give a workshop nearly every year. Recently I was asked to do a workshop in Osaka, on everyday materials and the patience to work with them. I developed a concept to work with students, which consists of using cheap materials and breaking them down—cutting them, drilling them, and then repairing them. This way I think one can really learn about materials. It was interesting for me to work with Japanese students because they seemed to be so sensitive to authority and gaining approval. I really had to convince them they could break stuff and be a little messy at first. The final results are always so beautiful that it proved to be an effective technique! If I were to sum it up in one line, it would be “Don’t please me, but surprise yourself.”

What has caught your interest recently, in the jewelry field and beyond? Is there an exhibition you’ve seen or a book you’ve read that you’d like to bring to our readers’ attention?

Beppe Kessler: Last week I visited the Rembrandt-Velazquez exhibition in the Rijksmuseum. Twenty-six pairings of 17th-century paintings, by Spanish and Dutch artists, are brought together in an intimate display that puts them in close dialogue. Recently, I also read a book about the life of the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, written by the French author Marie Darrieussecq. The original title is Être ici est une speldeur, which in English is Being Here Is Everything. It moved me. She never sold more than two paintings during her short life, but she was deeply passionate about painting and would dedicate most of her time to it.

One last question, which I always ask when interviewing an artist: You’ve been active since the late 70s, and it’s amazing to see how creative you are, still. How did you never get bored with art?

Beppe Kessler: People often ask me that. I’m not sure, to be honest. All I know is that whenever I’m not making—say, because I’m traveling—I get unhappy after a couple of weeks. I mean, I can cook … but I need the empty canvas in front of me to know who I am and where I’m at. I do get periods when I’m bored, when I can’t find something that surprises me, and I repeat myself. But that’s when I have to trigger myself into looking for something new. And drawing is the place I always go back to, whenever I need new inspiration.