Art jewelry resists easy definition. That’s because it explores, questions, and challenges the meaning of jewelry. The jewelry historian Toni Greenbaum says that art jewelry, like art, has embodied meaning. This means it is made to communicate an idea. Most jewelry is designed only for adornment. Without embodied meaning, it is not art jewelry.

People call art jewelry by different names: contemporary jewelry, studio jewelry, and author jewelry, among others. In his 2013 book, Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective, Damian Skinner focuses on other points. In summary:

Art jewelry is contemporary: It’s “of our time” and international. But it includes 70 years of objects and some dramatic changes in approach.

The studio craft movement shaped art jewelry: After World War II, the American government’s G.I. bill gave returning soldiers money for education. More people than before could afford college. Many of them studied art or craft. Studio craft developed as a result.

Studio craft isn’t defined by ideas or appearance. How the work is made is what’s important. Studio jewelers are independent. They handle their materials directly. And they make one-of-a-kind jewelry, or small runs. The studio jeweler both designs and fabricates each piece. (Assistants or apprentices may help.) They work in small, private studios, not factories.[1]

- Contemporary jewelers tend to shy away from mass production

- The special qualities of the materials are central

- Both the maker and the wearer or owner value individuality and artistic expression most

- Contemporary jewelers follow the model of the art world rather than mainstream commercial jewelry production. They distribute their work through dealer galleries, accompanied by artist statements, catalogs, etc.

It is directed toward the body: Jewelry is one of our oldest forms of creativity. It has a rich record of object types, materials, and relationships to wearers. Most, but not all, contemporary jewelry is designed to be worn. When it can’t be worn, art jewelry may also reference the body in some other way.

But the wearer is often forgotten. Makers spend lots of energy thinking about jewelry as a form of artistic expression. It’s more about the maker’s ideas than the idea and possibilities of jewelry. Still, the ideas around the wearer, wearing, and the body set contemporary jewelry apart from other kinds of craft and art. As a symbol, jewelry links the private and public body. This lets art jewelers examine definitions and interpretations of the body. Their artwork is therefore not just decorative.[2]

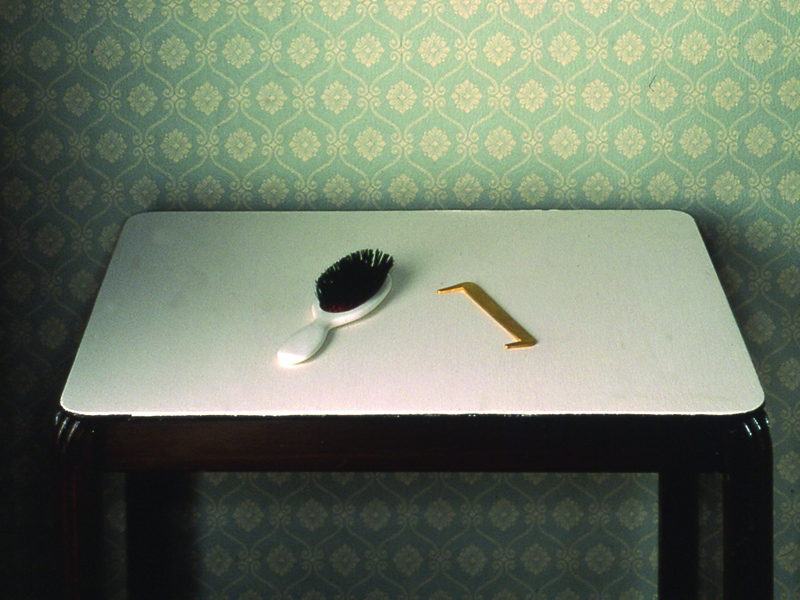

It’s self-reflexive. Contemporary jewelry looks at itself. It examines the situations in which it takes place. Its makers pay attention to the wider field of jewelry and adornment. Contemporary jewelers often work in a critical relationship to the history of jewelry-making. Their jewelry might question that history and comment on it.

Contemporary jewelers also examine the spaces in which they show their works—galleries or museums, for example, or books and catalogs. Not all contemporary jewelry examines itself to the same degree.

It’s surprising how many kinds of objects and practices fit under the term contemporary jewelry. Skinner’s points don’t always agree with each other. It isn’t easy dealing with uncertainty. But the contradictory qualities of contemporary jewelry make it interesting.

[1] Kelly L’Ecuyer, ‘Introduction: Defining the field’, in Kelly L’Ecuyer (ed.), Jewelry by Artists in the Studio. Boston: MFA Publications, 2010, p.17.

[2] Linda Sandino, ‘Studio jewellery: Mapping the Absent Body’, in Paul Greenhalgh (ed.), The Persistence of Craft: The Applied Arts Today. London: A&C Black, 2002, p.107.