The critique of preciousness is an important idea in art jewelry. This concept questions the idea that the value of jewelry is tied to the precious materials from which it’s made. In his 2013 book, Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective, Damian Skinner focuses on other points. In summary:

Most jewelry ranks materials. It considers precious metals and gemstones more valuable because they’re more rare.

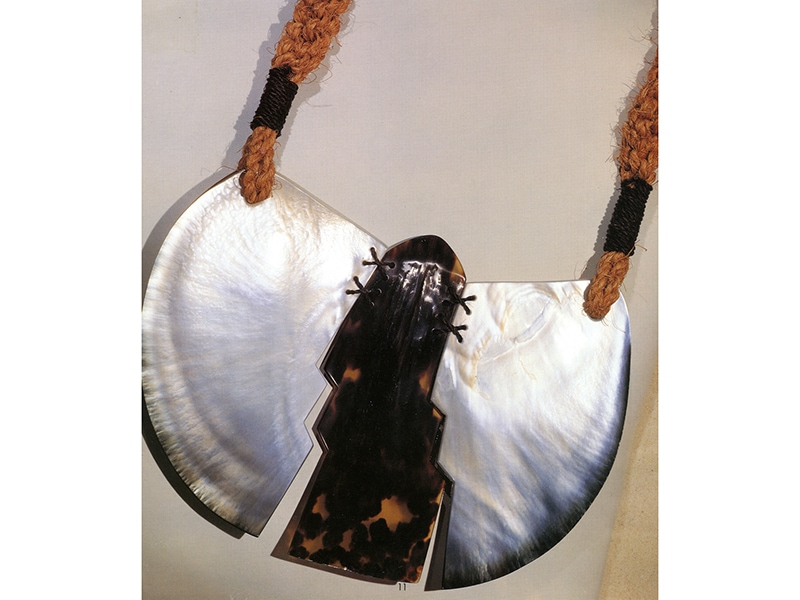

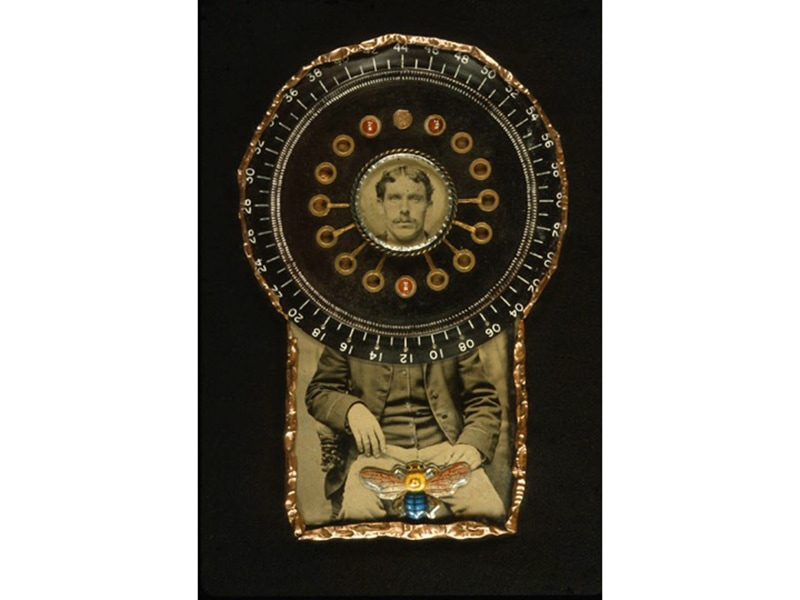

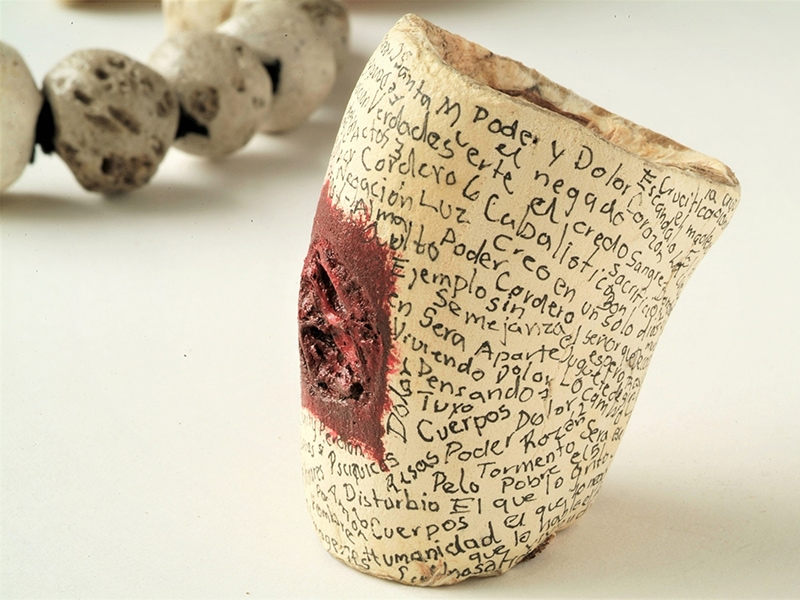

But the critique of preciousness separates the value of the jewelry from the value of the materials used to make it. In art jewelry, gold and silver can be valued just for their beauty, not for their worth. This idea is called material relativism. It opens up the idea of using materials other than those commonly seen in most jewelry. Art jewelry makers turn things upside down by using low-worth materials in their work. Some even use things viewed as trash.

To give an example: a diamond solitaire is about value, skill, status, and tradition. It accepts all these things as givens, and sticks comfortably to the customs that have developed around such rings.

But an art jewelry version of a diamond solitaire ring takes a different approach. How? It knocks over the notions of value, skill, status, and tradition that make such rings meaningful. It often does this by using forms or materials that disrupt expectations and raise questions.

The critique of preciousness started in the 1950s and 60s. It began with German goldsmiths. They still used precious materials such as gold, but they focused on artistic expression rather than on making traditional jewelry. Dutch jewelry experiments in the 60s introduced modern materials, such as plastic. Those makers put jewelry across the entire body, not just on the common places.

Freed from a limited notion of value, contemporary jewelry was born. Over the next 30 years a number of makers argued about where the worth of jewelry could come from. (They did this verbally and in the objects themselves.)

- Many believed the value came from artistic expression

- Some thought it came from unique, new ways of interacting with the body

- Others said it came from the possibilities of contemporary jewelry as an affordable and democratic object

- Radical American jewelers of the 1960s attacked good taste and elegant design[i]

Once traditionally valuable materials lost their hold on jewelry makers and they were no longer interested in making work only a few people could afford, a different kind of investigation could begin.

At its weakest, the critique of preciousness becomes a search just for new, unique materials. It is as if creating jewelry from a material never used before for making jewelry proves that the object is truly a piece of art jewelry. This ties back to the idea of contemporary jewelry as primarily a form of artistic expression. At its strongest, the critique of preciousness causes jewelers to continue arguing about the importance of value, which is such a traditional part of most jewelry, and to constantly question the field of jewelry-making itself.

[i] L’Ecuyer, Kelly Hays. “North America.” In Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective. New York: Lark, 2013.