Every August, the British edition of Vanity Fair magazine publishes a supplement or bonus issue called Vanity Fair On Jewellery. Mimicking the look and feel of the original, Vanity Fair On Jewellery is, as the name suggests, dedicated to the glittering world of luxury or fine jewelry. It’s a somewhat uncanny reading experience, since the real Vanity Fair has its own share of advertisements for exactly this kind of jewelry, and quite often jewelry “news” makes it into the “Fanfair” section of the magazine, where the lives and object loves of the glitterati are celebrated. Effectively, Vanity Fair On Jewellery takes part of the DNA of the original and puts it on steroids, remaking the editorial vision of the magazine through an exclusive lens of high-end jewelry.

Which brings me to the purpose of this article, since this bonus issue—something that you get for free with your August issue of Vanity Fair—represents, from the perspective of the contemporary jewelry field, unimaginable wealth and cultural power. Vanity Fair On Jewellery isn’t a pamphlet or brochure demurely tucked into the pages of the magazine proper, but rather it is a separate publication, as thick as the real Vanity Fair and with the same publication standards—glossy images, celebrity subjects, articles that range from barely disguised press releases to serious profiles and thematic investigations. As the English proverb puts it, the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence, but if the backyard of contemporary jewelry’s house is nicely mown lawn and some shrubs, this is like looking into fine jewelry’s backyard and realizing the lawn’s been replaced with an infinity pool and cabanas, with drinks that have those little cocktail umbrellas, and an attentive staff to serve them.

While I’m a little envious of what Vanity Fair On Jewellery represents, in this article I want to try and locate the ideological differences between the world this magazine represents and the contemporary jewelry world I’m part of. In a time when many people are asking how to open up the somewhat insular field of contemporary jewelry to audiences and practices and institutions that make up the visual arts and realm of culture, what might we learn from taking something like Vanity Fair On Jewellery seriously?

- Advertisements for jewelers, which involve models or celebrities wearing the jewelry; staged scenarios, usually jewelry against some kind of distinctive background; and the jewelry by itself floating in space (the least frequent).

- Illustrations of jewelry mentioned in the text, which, as you would expect, are concerned with capturing the detail of the objects and draw on visual strategies that aren’t too dissimilar to the ways in which contemporary jewelry is photographed.

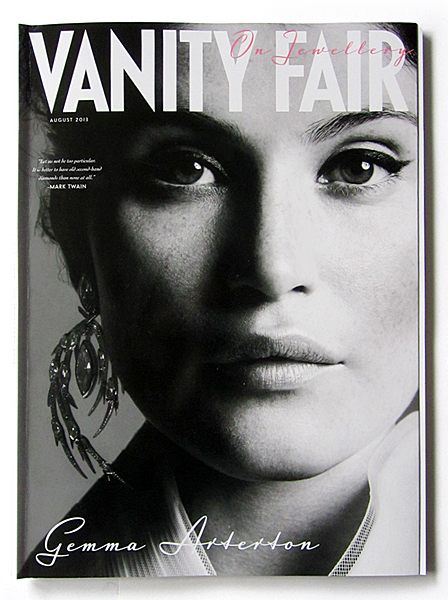

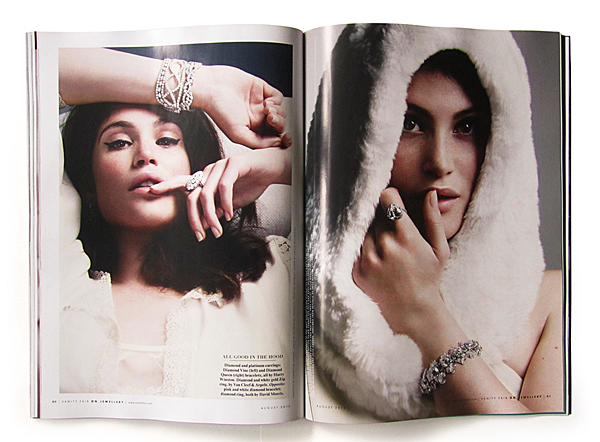

- Photo shoots, in this case three: actor Gemma Arterton modeling fine jewelry and haute couture; a spread about pearls, worn by a fashion model in a variety of bathing suits to invoke the theme of ocean or water; and a photo shoot of fine jewelry—some with natural motifs (butterflies, flowers, snakes)—staged against, on, and around, exotic flowers that float against a white background.

The photo shoots are most obviously different to what you find in most contemporary jewelry publications. While there has been a recent surge in precisely this kind of activity —Noon Passama, Hanna Hedman and Denise Julia Reytan, just to name a few, have been presenting their work in ways that are related to fashion photography—it isn’t common practice to present contemporary jewelry in a sequence of themed images, possibly because contemporary jewelry, unlike fashion, hasn’t had the magazines that require and support such display strategies. And despite the growing tendency noted above to collapse the distinctions between studio craft and fashion, in general, people modeling contemporary jewelry don’t act like models, no matter how pretty they might be or how unrealistically attractive. They are not groomed in the same way, and they don’t pose in the repertoire of gestures that models in mainstream fashion-savvy magazines such as Vanity Fair have available as the tools of their trade.(There is a subculture of contemporary jewelry photo shoots using models produced by the likes of Gemma Draper and Volker Atrops. These resemble the fringe of fashion photography with its deliberate anti-mainstream adoption of techniques and strategies borrowed from other cultural fields such as indie cinema and fine art. This suggests that contemporary jewelry imaging isn’t so much opposed to fashion as a whole, but rather it is opposed to mainstream fashion values.) And while contemporary jewelry has in the past been photographed against nature, this would now seem quite old-fashioned, perhaps too close to the conventions of the product catalogue.

These images take their cues from advertising and the product catalogue. The jewelry is photographed in a very specific way that indicates commodity rather than art object. When the jewelry is shown on the body, you notice a couple of things. First, these are models, toned and tanned and groomed, quite different to the bodies that usually wear contemporary jewelry. Also, the work is worn and displayed through poses that belong to the repertoire of the fashion industry. (Hand artfully touching face so ring is prominently displayed? Check. Head turned to the side so earring is clearly visible? Check. Back arched so necklace hangs in a straight line from shoulder to buttocks? Check.)

The link with celebrity is incredibly important in how these images of jewelry function. In many of these photographs, it matters who wears the jewelry, whether it is actors such as British Gemma Arterton on the cover and in the main photo shoot or American Mila Kunis in an advertisement, and so on. Contemporary jewelry also uses celebrity. Quite often jewelers use people of importance as models to aggrandize their work—yes, that is a leading jeweler/museum director/editor of AJF wearing my piece—but the difference here is one of scale. Very little, or no, contemporary jewelry could get access to real celebrities like these, who are actually famous outside the field.

If the images reveal a number of areas of difference, what is the same? Well, I’d say the tone of upbeat, positive cheerleading links Vanity Fair On Jewellery with most contemporary jewelry publications. Just like in this magazine, which is designed to sell and promote the work and therefore can’t be critical, contemporary jewelry publications also inevitably promote and celebrate, texts acting as praise and support and very infrequently criticism. In each case, it is motivated by different factors (a commercial imperative in the case of Vanity Fair; a model of craft solidarity in the case of contemporary jewelry), but the end result is surprisingly similar.

Sometimes, from a contemporary jewelry perspective, the text is unintentionally hilarious. Author Alice B-B, for example, tells us there are two kinds of wearers of jewelry: sheep, who diligently follow the flock (and fashions set by others), and unicorns, “style originals, women who have chosen jewelry to express themselves: Nefertiti, Cleopatra, Marilyn, Elizabeth Taylor, the Girl with a Pearl Earring, all of whom chose pieces that extended their characters and told their stories.” The extraordinary gaps in logic required to conflate these various individuals is impressive. Presumably, the author is thinking of Cleopatra as played by Liz Taylor, and the “Girl with a Pearl Earring” isn’t a person so much as a character in Vermeer’s painting, Tracy Chevalier’s book, and the movie based on it. (I’m surprised Alice B-B didn’t just mention Scarlett Johansson, the actor who played the part.)

But listen to what passes as daring—style leaders such as designer Miuccia Prada and actor Gwyneth Paltrow choosing a vintage melanine bracelet from a market in Ibiza or a designer piece inspired by African adornment. Anyone working in the contemporary jewelry field knows that there is much more radical jewelry being made that can truly be said to manifest distinctive ideas about personal identity and style. (Have you heard this explanation of why contemporary jewelry collectors/wearers tend to be older women? It’s a way of attracting attention in a world where women over a certain age become invisible because they are no longer objects of sexual desire. Whatever you think of this as an analysis, it certainly highlights the expressive potential of contemporary jewelry and its transformative potential in the realm of identity and social interaction.)

An article about jewelry that supports worthy causes doesn’t engage with the relationship between the object and the act of wearing other than suggesting that part of the profits go to charity. James de Givenchy’s luxury jewelry made from the steel of AK-47s is about removing the weapons from warzones, and yet nothing of this intention or history is registered in the object or how it is worn. The same is true of other examples discussed in the text, such as Bulgari’s Save the Children ring—the only reference to the charity is tucked safely inside the band, while the brand name is blazoned prominently along each rim. Then again, that particular program has, since 2010, raised $20 million for the Save the Children charity. While we might wish for an artistic engagement that does more to transform the object and how it operates as a way of raising consciousness, there’s no denying that real change or action is an outcome here, unlike most art or contemporary jewelry projects that are worthy, conceptually rigorous, and basically ineffectual at instigating transformation in a political sense.

And yet, despite a certain journalistic lightness, there is an ongoing difference that I find most tempting and suggestive. Ultimately, Vanity Fair On Jewellery pays attention to the purpose and function of jewelry as jewelry—a certain kind of object that operates in the world in relation to users. Vivienne Becker talks about David Bennett’s revival of the talismanic meanings of jewels and gemstones. Chairman of Sotheby’s jewelry in Europe and the Middle East, Bennett also creates amuletic jewelry for private clients based on astrological readings. Here, the jewelry and its materials are intended to facilitate transformation, healing, and harmonization for the wearer. The jewelry is perhaps unsurprisingly closely aligned with the kind of ancient objects you find in the Victoria & Albert Museum or the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the middle ages and Renaissance. Bennett’s work is conceived for the same purpose—to act, to be efficacious, to have agency. As the author suggests, these jewels go “way beyond bespoke, to connect on a deep physical and emotional level with the wearer, encapsulating the owner’s persona.”

Whatever you might think of the science or philosophy, the idea of the amulet is really fascinating and a rich discussion of the particular and singular potential that jewelry has as a relational object and practice. Maybe the difference here is that fine jewelry’s bid for agency invokes the user as a person rather than an undefined viewer, reader, or museum visitor, which tends to be the case in contemporary jewelry discourse. Throughout Vanity Fair On Jewellery, we get a parade of actual people who wear and own and interact with jewelry. That’s really uncommon in the contemporary jewelry field, where even the named collectors tend to have an unexamined relation to the work they have amassed. (The main point is always to talk about what these objects mean within a history of contemporary jewelry rather than what they mean to the individual who collected them.)

Another article by Diana Scarisbrick about portraiture and jewelry is a serious art historical account of the nature of jewelry since the early Renaissance to the present as represented in fine art paintings. Again, the wider social and cultural meanings of jewelry are stressed and explored, and the somewhat shallow reveling in luxury and preciousness that characterizes the magazine overall finds depth by exploring the history of jewelry and its particular character as an object to be worn, and thus to construct and sustain identity and social relations.

And yet, reading this issue of Vanity Fair On Jewellery, I find a surprisingly rich conversation about what I would call the relational potential of jewelry—how it operates in the world at large and what kind of meanings can be attached to it. I know that part of the novelty is having craft values and conversations replaced with a different conversation based on monetary value, and I’m sure this would become, after a while, as annoying a default setting as the endless craft discussions of how something is made, from what, and how it reflects the artistic intentions of its maker. But this publication also makes me realize that a serious engagement with the relational jewel will necessarily lead beyond the borders of the contemporary jewelry field. There are things to be learned from luxury or conventional jewelry that the particular and peculiar qualities of the contemporary jewelry field simply don’t allow. While I’m not going to give up reading all those Arnoldsche monographs, I’m also going to recognize that reading Vanity Fair On Jewellery might not be as frivolous as I initially imagined.