Susan Cummins: La Frontera addresses a current political moment related to immigration and specifically to the border between the US and Mexico. What led you to pick this issue as your theme?

Lorena Lazard: The idea for this exhibition has been in my mind for some time. I have a masters degree in sociology, so I have a long-standing interest in political and social issues. Especially, I think the Mexico-US border is an issue that is contemporary and important at this juncture.

While defining the ideas for the project, I realized that it should be on view in both countries. In Mexico, the Museo Franz Mayer was the ideal space, and in the United States, Velvet da Vinci gallery. Elizabeth Shypertt and Mike Holmes took an interest right from the outset. They have plenty of experience working with international artists and have put on exhibitions with political themes. They understand them and are completely open to them. And because this is a bi-national issue, I thought it was important the juries have both the North American and the Mexican viewpoints. Without a doubt, Elizabeth’s and Mike’s involvement was key to the success of this exhibition. This show includes US and Mexican artists as well as others from outside these countries.

Elizabeth Shypertt: Both Mike and I jumped at the idea. It is such a relevant topic, and though we don’t live on the border, everyone on both sides and beyond is affected in some way. There aren’t very many jewelry exhibitions that I can think of with political themes, but I see a lot of work by American jewelers with undertones of political topics.

Why do you think curators don’t pick up on this theme more often?

Elizabeth Shypertt: When we tried to travel the Anti-War Medals show in the United States, we talked with various institutions whose curators were very interested. In the end, not one venue took the exhibition because of funding coming from board members who did not like the theme and wouldn’t approve the project. Many institutions simply can’t risk losing their funding sources so won’t take on controversial projects.

Mike Holmes: There are curators, and there is the marketplace. They have different motivations, and although we routinely show political work, such as that of Timothy Information Limited from London, Robert Ebendorf, or many of the pieces in our Buttons and Badges exhibition of last year, not everyone wants to wear their political views on their bodies. But there are curators who seek out political work, and we are happy that they support us as much as they do.

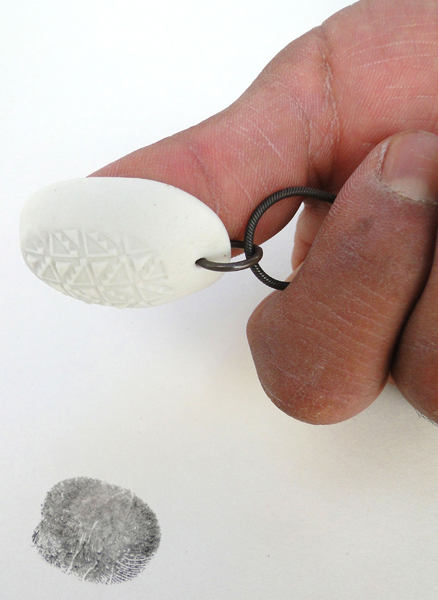

Elizabeth Shypertt: One of the pieces that touched me the most is by Lorena Lazard. She took soil from Tijuana, Mexico, and from San Ysidro, California, and combined with other materials, made pendants. Her artist’s statement says, “Soil: So similar and so different … such a simple idea with such wide-reaching implications.”

Tom Hill’s pendants—a turtle, a frog, a newt—are animals that live in the border area, and something that almost no one thinks about. The wall not only prevents humans from crossing, but also has dire implications for the wildlife that lives there, that used to be able to cross back and forth to search for food and water and is now limited to one side or the other.

Mike Holmes: Pieces reflecting specific stories coming out of border issues were very surprising. Kevin Hughes’s pendant made with a water jug handle is haunting, powerful, and infuriating. Aline Berdichevsky’s Lightvessel pieces—about parcels thrown to migrants riding the La Bestia freight train—are another excellent example of how jewelry can be as successful as any other art form in dealing with complex issues in provocative ways. I don’t know how the artists researched these poignant stories, but they make the exhibition.

Lorena Lazard: From the beginning, it was clear that a balance of Mexican and North American artists needed to be included. The response from Mexican artists to the call for entries was very strong. Although most of these artists do not live in the border region, they all have opinions, feelings, and emotions about it. Mexicans are highly sensitized to matters involving their northern border, and everyone knows someone who has gone over to “the other side” (legally or illegally). It is something very real for us, and although we might not experience it directly, it does affect us every day, and this has been reflected in the pieces shown.

Also, I think that globalization, the Internet, and social media make it possible to gain an immediate and in-depth understanding of what is happening around the world. Artists in Europe, Latin America, and even Australia can have an opinion about this border.

Mike Holmes: In the call for entries, we included a number of English and Spanish website links that dealt with various aspects of La Frontera. Partly we wanted artists to be well informed about the subject, but also we wanted to point out the complexities of the region. Depending which way you are standing, looking north or looking south, the border looks very different. I’m very happy we had Lorena working from Mexico, because she was very sensitive to how the exhibition was coming together from a Mexican point of view. But being from California and living in San Francisco with a huge Latino population, I knew there were no simple responses to the issues.

Did you see a somewhat different approach in the way the US jewelers and the jewelers from outside the US approached this topic? If so, can you describe it?

Lorena Lazard: This was possibly one of the biggest surprises. In the beginning, I thought that perhaps the artists would choose their themes on the basis of their own reality. In this sense, there is no clear difference in the jewelers’ approach. They have similar reflections and concerns.

In the end, I realized that the artists addressed universal themes in this exhibition—human rights, hopes, dreams, fears—feelings and thoughts that are ultimately all human.

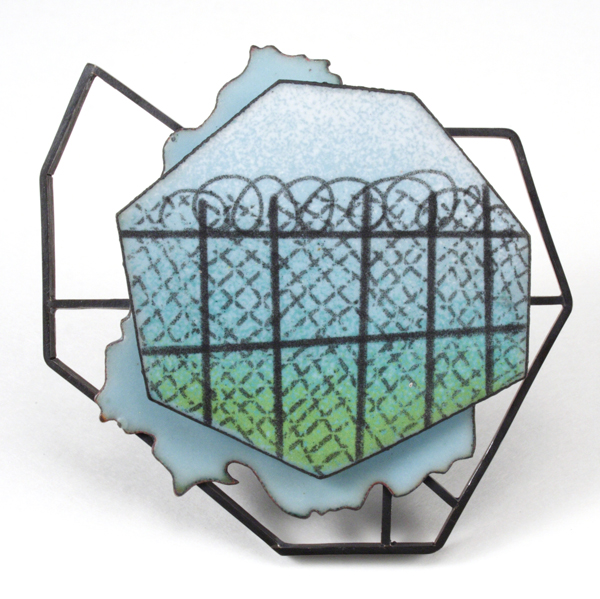

Mike Holmes: I guess I was expecting a US point of view differing from a Mexican one. But, this didn’t happen, and the prevailing point of view was one that was critical of the US policy. I was also surprised that some issues were not really covered in the show. The environmental impact of the construction of the wall was not much considered, although Tom Hill’s enameled Milagros series does look at endangered desert animals. And the importance of the American demand for illegal drugs on border violence and the growth of the Mexican drug cartels are topics missing altogether.

Lorena Lazard: The Museo Franz Mayer is Mexico’s foremost museum for decorative arts. It’s a major cultural space with a strong capacity to reach a wide and diverse audience.

The reception for this exhibition surpassed all our expectations. 500 people attended the inauguration, articles appeared in more than 40 media outlets—including leading national and international newspapers, radio, magazines, television, and social media—but above all, we were amazed by the reaction of the people who went to see the exhibition.

The border is a complex subject, but with their work, the artists managed to raise visitors’ awareness of it. One time, I was in the museum and a woman came up to me in tears. She had come across the exhibition by accident and felt extremely moved by the stories told by the artworks.

Also, contemporary jewelry is not well known in Mexico. With this exhibition, many people were able to see it for the first time. I think it was a good decision to make an exhibition about such a thorny, controversial issue. One of the questions I heard being asked most frequently was, “How can you talk of death, migration, and violence using a necklace or a brooch?” This type question opened the door to wide-ranging discussions and reflections.

What do you think viewers of La Frontera will learn from it that they might not know? What did you learn?

Elizabeth Shypertt: I learned that this truly is a universal theme. In some way, most everyone has been touched by a border controversy. If the viewers of La Frontera can take the time to read the artists’ statements, I know they will be as profoundly touched by the work and what the artists have to say about it as I was. It is an amazing body of work.

Lorena Lazard: When I first began, I had a clear, academic knowledge about the border situation. But, some of the stories the artists told confronted me with a less theoretical, more palpable human reality.