“The real is produced from miniaturized units, from matrices, memory banks and command models—and with these it can be reproduced an indefinite number of times.”

—Jean Baudrillard

I assume most AJF readers are familiar with the film trilogy The Matrix, in which protagonist Neo (played by Keanu Reeves) leaves “reality” behind and leaps into the matrix. In the film, what we know as reality turns out to be no more—in Baudrillardian terms—than a “generation” by the matrix “of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.”

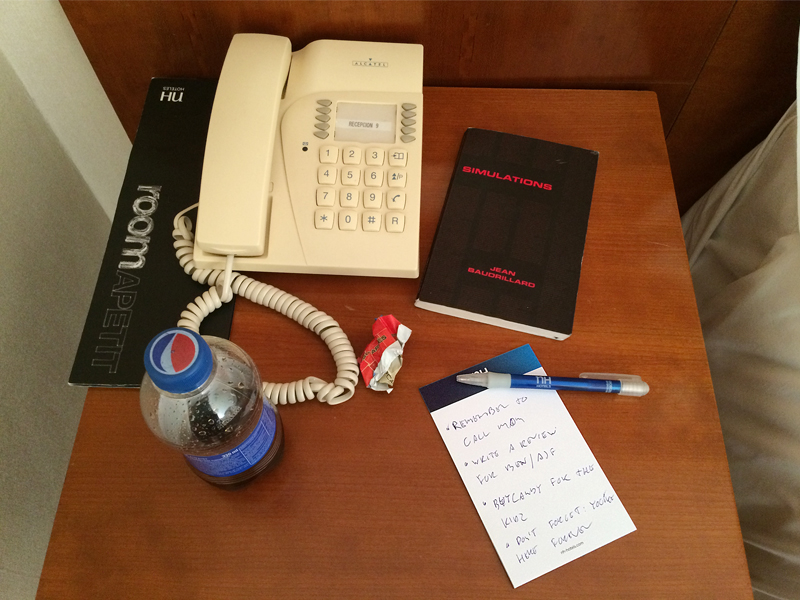

It is no secret that the Wachowski Brothers, who directed the film, were strongly influenced by two relatively short (and erratic) essays published in booklet form in 1983 under the title Simulations. The book even appears on the screen during the film.

Baudrillard established himself as a bad boy intellectual in France with his infamous essay Oublier Foucault (Forget Foucault) from 1976/1977, in which he vigorously attacked the French intellectual for his History of Sexuality. But he did not become a well-known name in the US, or the rest of the English-speaking world, until Simulations. The book never existed as such before the two essays were translated into English. “The Procession of Simulacra,” the first essay in the book, and also the most provocative because it was theory written as fiction, was previously published in Simulacre et Simulations (1981). The second essay, “The Orders of Simulacra,” previously published in L’Échange Symbolique et la Mort (1977), was written in a slightly more academic language, as a kind of history of “the three orders of appearance: the Counterfeit attached to the classical period; Production for the industrial era; and Simulation, controlled by the code.”

For many, Simulations was the work of a prophet, not least for the art world, which succumbed to his ideas and used them to define what appropriation artists like Jeff Koons and Barbara Kruger, or the “pictures generation” with Cindy Sherman, Sherry Levine, and Richard Prince, were about. (Baudrillard later disappointed the art world by claiming that “all of the openings, hangings, exhibitions, restorations, collections, donations and speculations” were part of a conspiracy to conceal that art didn’t exist.)

In Simulations, ideas that had been brewing in Baudrillard’s mind since his PhD thesis (1966) and his first books on the post-war consumer society (namely The System of Objects [1968] and The Consumer Society [1970]) reached a new level. In these early works he built on Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle—a neo-Marxist analysis of the capitalist society—and the semiotics of Ferdinand de Saussure. He made efforts to combine these two systems of thinking but eventually abandoned the Marxist idea of base and superstructure. With Simulations he also left traditional scientific argumentation altogether and launched his own “nihilistic” form of writing that better suited his idea that no objective, outside position, from which one could observe society, was possible. The book shows how the real and the image of the real (representations) have imploded into an order of simulacrum where there is no reality behind the “surface”—simulations serve the purpose of concealing the fact that there is no reality at all. In a later book he calls this the perfect murder—the real has been killed by capitalist society through overproduction—but the real is kept artificially alive by systems that act upon its existence (thus concealing the fact that a murder has taken place).

I read this book for the first time when I was writing a master’s thesis in theater theory at Oslo University. My subject was Andy Warhol, his pop art persona, and the theatricality of the social. Baudrillard’s concepts of simulation and simulacra strongly suggest that we live in an age of theatricality. A theatricality without a “reality” to oppose it, a theatricality that conceals the fact that there is no reality: All the world’s a stage and we’re merely players, as Shakespeare wrote in As You Like It.

Baudrillard wrote Simulations as a novelist on speed rather than as a scholar, sociologist, and philosopher. This way of writing underlines the “message” of Simulations better than a typical scientific analysis would: The form shows that Baudrillard takes into account that his writing is neither objective nor external to the hyperreal, but is a part of it. It analyzes and constitutes the hyperreal at the same time.

For me the book provided a valuable tool for rethinking consumer society and mass communication. At the same time, it has made me conscious of the fact that writing a text is not merely an analysis of a phenomenon: It also serves to shape that phenomenon.

In retrospect, the book and much of Baudrillard’s oeuvre can be read as describing the social structures that have led to the digital frenzy of cyberspace and to an “atomization” of identity—a situation he often refers to as the “orgy of modernity.” (Baudrillard himself never uses the expression “postmodernism,” even though he is considered as one of the most significant postmodern thinkers.)

The thinking of Baudrillard keeps appearing in my own texts and re-reading the book today reminds me how much it has shaped the way I think about reality, society, and art.