For years after I graduated with my BFA in jewelry design and metalsmithing, I struggled to reconcile the practitioner that I was within academia, the goals and beliefs that I held for and about myself, with the reality of the creative economy that I faced. I felt shocked by how inaccessible people found my work, how bewildered they were by my process and my price points. I had been praised within my program for my work ethic, my designs, my craftsmanship, and my concept—so why could I not get anyone to care now? What was I missing?

My studio practice grew increasingly self-conscious as I grappled with the shame I felt at my failure to gain gallery representation, start selling my pieces, and support myself as a contemporary artist. I translated my work into production pieces: earrings and pendants I could build from cast components, priced well below the cost of my materials alone; still I failed to garner interest. Soon I was too ashamed of myself and my work, and too drained from the six days a week I was working as a waitress, to keep fighting to convince people that I was worth anything. I couldn’t afford materials, I couldn’t afford rent, and eventually I abandoned my creative practice, but I never stopped thinking about what had gone wrong.

I blamed myself (my work wasn’t good enough, I didn’t find the right market, I didn’t try hard enough, the usual chorus), but the more I spoke to my peers and lamented my failure, the more I realized that they were feeling the same way—bewildered by the creative marketplace and questioning everything they had believed about the value of their creative capital. Had we not paid close enough attention in our “Entrepreneurship for the Arts” class?

Sobering up after my pity party, I thought more objectively about how I had come by my idea of what constituted “success” and “failure” in the contemporary jewelry field. I evaluated my illusions about the viability of a financially independent existence based solely in contemporary jewelry practice. I started considering the practice of myth-making within the 21st-century post-secondary art institution, particularly surrounding craft education—how illusions and outdated assumptions about market viability, function, and cultural significance are fostered and perpetuated in post-secondary education, as well as in museums, and how this misdirection affected emerging practitioners like myself and my peers. I pursued my line of questioning and, long story short, now I have an MA in the history of design.

Our field has very little historical scholarship, in part due to its relative youth. Most historical examination revolves around individual practitioners of note, focusing on their genius, vision, and “influence.” Compelling as it may be, these eulogies will not drive our discipline into the future. The endless qualification of contemporary jewelry into the Fine Art or Craft paradigm because of this or that theory about skill or intent, and the subsequent praise or vitriol with which it is met, contributes little to the reform of a system that continues to lose relevance and alienate practitioners.

In my graduate research, I examined the birth of post-secondary craft education in America, its adoption into the academic fine art institution, and contemporary art jewelry’s subsequent birth, evolution, and academicization in order to build a foundation upon which to encourage discussion of the position of the contemporary practitioner today. James Elkins, in Why Art Cannot Be Taught: A Handbook for Art Students, observes that the danger in allowing contemporary art instruction to progress unexamined is that the process of instruction begins to appear timeless and natural, obscuring its biases as well as its possibilities. Without contextualizing contemporary art jewelry practice—without fostering an active, honest, and, above all, critical discourse surrounding how we learn, teach, practice, exhibit, and make money, our discipline will not successfully bridge the gap between the glory days of the late 20th century and the realities of the 21st.

From our present-day standpoint, entrenched as we are in the history and traditions of Fine Art institutional instruction, it is easy to assume that craft education is basically art education devoted to the creation of different objects—both involve the study of materials and techniques and the mastery of tools—but, in truth, craft education in America developed as a distinct method. Borrowing from industrial design and business and appropriating methodologies from fine art instruction, craft education evolved as a separate discipline granting the practitioner a degree in the fine arts, yet placing significant value on a practical knowledge of the creative market and the ability of the American craftsperson to maintain a livelihood by contributing what the buying class in America once considered a vital domestic product.

The earliest instruction taught professionalism and efficiency in the use of tools, work processes that adapted assembly line methods of hand production, and methods of recordkeeping to ensure that, post-graduation, the student would be capable of maintaining sound business practices. This facet of education is significant because despite the parallels and educational influences, these students were not becoming journeymen and masters as in the European apprenticeship system, and therefore would not be met with the same security. Their security lay in the responsible, professional handling of themselves and their labor in the marketplace, and this was acknowledged within their education.

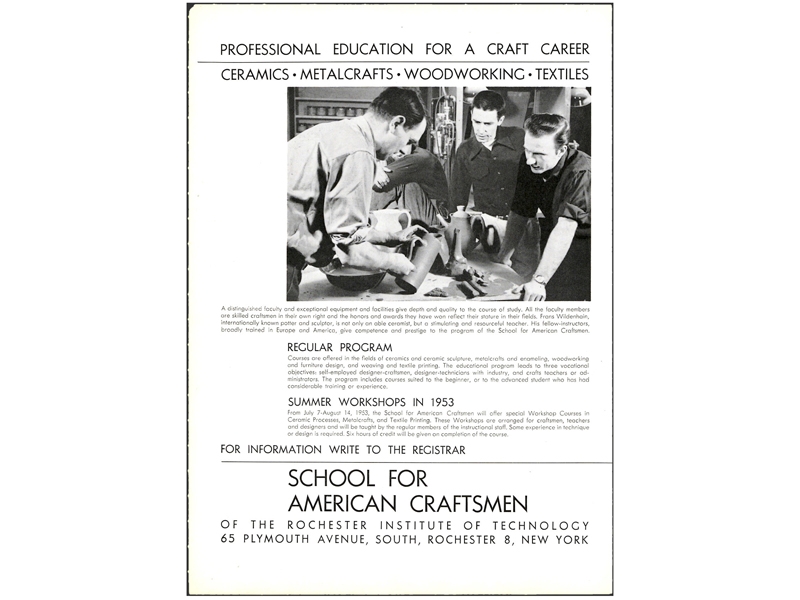

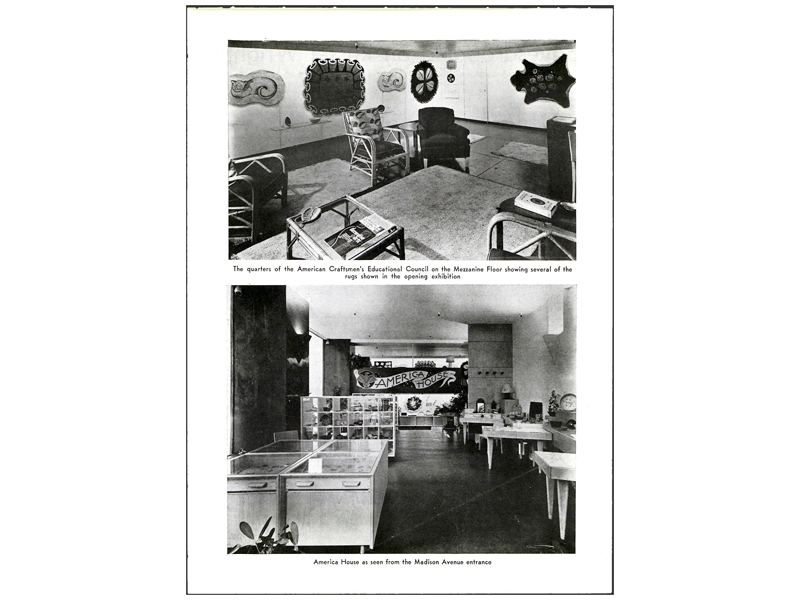

The founding principles of post-secondary craft education are rooted in the revivalist movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the creative economy in America was driven by a growing middle class that actively valued and supported the revitalization of the creative heritage of America; consumers had a vested interest in the growth of the American domestic product and in supporting the American creative class. They bought homes and invested in well-made, finely designed products that reflected their values. The School for American Craftsmen, the blueprint for contemporary fine craft education in the United States, was developed in partnership with America House, the American Craft Council’s retail shop in Manhattan, which opened in 1940. (The school still exists as the School for American Crafts at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, NY.)

America House sought to educate and inform public taste and consumption with a view to the promotion of American handcrafts, and built a belief in the investment value of craft objects; a system of education developed in response to the demand generated. America House served as a testing ground for practitioners experimenting with new designs, techniques, and marketing, affording students and emerging professionals an opportunity to confront merchandising procedures and marketplace interaction, making the transition from school to professional life “much less disturbing,” in the words of Harold Brennan, an early director of the School for American Craftsmen.

Contemporary jewelry, ceramics, textiles, and other craft media and the discourse surrounding them were not, at this time, preoccupied with the attainment of legitimacy within the Fine Art paradigm, and culture benefited from the accessibility of the contemporary craft narrative. As this changed and post-secondary craft education became more deeply entrenched in the contemporary art academy, conceptual thinking became the name of the game for so many. Values within craft production and academic discourse shifted toward valorization of objects that eschewed marketplace values, rejecting commodification and subverting traditional relationships to concepts like consumer culture, wearability, preciousness, skill, the nature of adornment, and, in sum, the very origins of the discipline itself. It is this transition and the cultural and economic shifts that have accompanied it, along with the fetishization of the dialogue surrounding contemporary jewelry production by fine art and craft academics, that today demands examination and discussion.

I have watched talented young jewelers stand in critique and speak beautifully about the relationship of their work to the body, the emotional effect their pieces will have on a wearer, how observers of the wearers of their jewelry will feel and be altered. I have heard them discuss the causes for which their work advocates and the concepts that led them to choose a certain design for a brooch-back. I have been one of them. I earnestly believed that there was a place for my work in the world—that it had value and meaning, contributed to society, and would be consumed, worn, and observed. Contemporary jewelers are trained to be academic practitioners of their discipline, and within their institutions there is immense pressure to engage in art theoretical discourse, despite the frequently extraneous language and practices it imposes. Conditioned within this system, emerging practitioners vie for the attention of The Art Jewelry World only to discover that it is a self-referential construct. The micro-hierarchy of the contemporary jewelry world is well established, highly respected, and bears no resemblance to the contemporary creative marketplace. Success in one has little to no bearing on the other; in fact, they usually stand in direct opposition.

Emerging practitioners face a creative culture that is more detached than ever before from the one that influenced the systems that govern their education and governed the education and professional lives of their mentors. Between contemporary jewelry education and the marketplace, a vacuum has developed, caused by the opposition of the dominant contemporary art jewelry narrative to the reality of the contemporary creative marketplace. The unwillingness of so many in the educational establishment to speak openly about the realities of today’s creative economy and the prospects of those who seek to support themselves with their artistic practice has manifested as the inability of a generation of practitioners to confidently assert their worth; not only the worth of the pieces they produce, but the worth of their skills, ideas, and labor. This issue parallels a dominant societal narrative surrounding the laziness and entitlement of millennials that is a convenient diversion from meaningful, productive discussion about the ways in which contemporary education is failing a generation of students. It boils down the disappointment and frustration of the most highly educated generation in history to a collective character flaw.

The advent of the digital creative economy has become more curse than blessing for traditionally educated practitioners. Creative commerce is democratized to the extent that any entrepreneurial maker can declare themselves a professional, and without effort on behalf of the art institution to maintain an engaged, educated public, along with the recession and subsequent adjustment of values surrounding cultural investment, the market has become flooded with pieces that undermine the investment value of contemporary jewelry pieces in society. For art jewelers, collectors were traditionally the middlemen who lifted their work out of obscurity and gave it value, and this concept has remained engrained in the education of contemporary practitioners, paralyzing them in the face of a democratized marketplace.

At the Cooper Hewitt’s Jewelry of Ideas seminar, marking the gift of Susan Grant Lewin’s contemporary jewelry collection to the institution, Iris Eichenberg, during her presentation, spoke to Grant Lewin directly, saying, “You gave my work a life outside my studio … you’ll never know what that means.” There have been and will be so many who will never know what that means, and for some it’s simply because they don’t believe they have the power to define and seize success for themselves. We must interrogate the systems that determine the future of our discipline and reject the assumption that bitterness is a natural byproduct of contemporary post-secondary education.