Materiality and our understanding of how a material changes the way we interact with the objects around us has always fascinated me. I consider this one of the main reasons why people are excited about seeing and interacting with jewelry objects—we get to touch and physically connect to the artist’s choices to get the full scope of what the piece means.

While in grad school, I encountered a term coined by my mentor and thesis head, Yevgeniya Kaganovich, to describe a piece that had been sitting on my bench for the better part of a semester. Similar to what most metalsmiths have on their benches, it was a quick study and exploration in materiality—to make sense of utilizing a material in a nontraditional application as a stand-in for a feeling or story. The term Kaganovich used to describe this study was “material fiction.” My thesis committee began using this buzzword to describe the intentional treatment of a material in such a way that it creates a whole new life, story, and fiction.

Jewelers and metalsmiths are not strangers to this concept of material fiction. Our uses of nontraditional materials and techniques (which keep evolving) have allowed us to be in a constant state of innovation. Incorporating found objects, plastics, rapid prototyped components, and so forth has become a creative and intellectual staple in the contemporary jeweler’s arsenal. These deliberate choices and treatments of material change the way we perceive the object before us. Our interpretation of the work relies heavily on the story that these materials tell, while our preconceived notions of the material shift from our traditional understanding of what it was in its previous life.

We transition from just creating meaningful jewelry to creating a new experience for the wearer and the viewer—touch, wearability, even haptic qualities are brought to a new light in how the audience interacts with the work. In a similar manner, the treatments of materials in installation art achieve the same purpose as jewelry objects; they raise new questions for the viewer and manifest as a new vessel for thought and spatial interpretation.

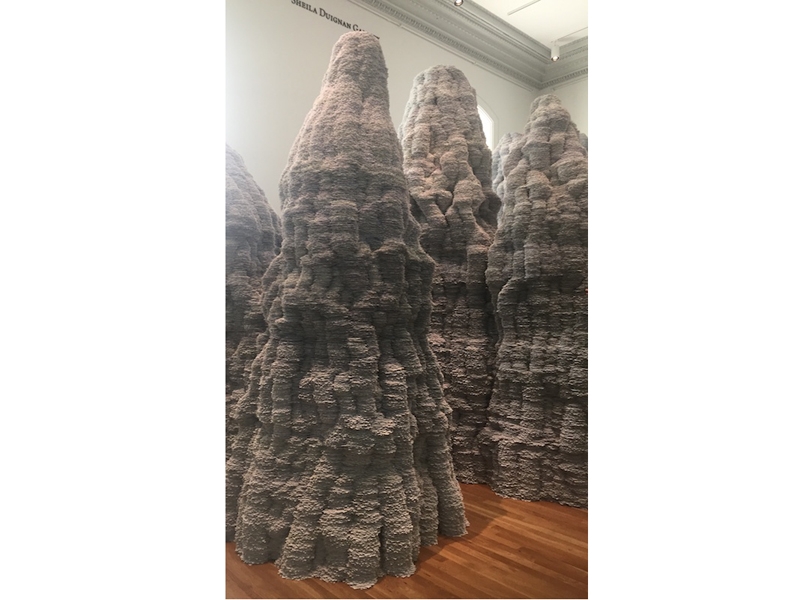

Repetitions of everyday recycled objects, for example, alter the viewer’s understanding and analysis of the singular object or material. Tara Donovan’s installations, for instance, transform our material perception of items such as straws, plastic cups, or index cards. She uses these materials to create a new fiction for the viewer, where the plastic cups are no longer cups, and the index cards in her piece Untitled, for example, become eerie, undulating towers in the gallery.

In keeping with the tradition of rule-based generative art, Donovan allows the materials to dictate how the piece and overall environment will shift and change form. She restricts her practice to a series of predetermined rules with material choice and how to use it. In each instance of Donovan’s work, the materials take on their own life and begin to grow throughout the gallery.

Yevgeniya Kaganovich and Susie Ganch, both jewelers by trade, have been working with similar approaches to alter the viewer’s understanding of the way we perceive, interact, and engage with material and environment. Each uses various plastic objects (bags, coffee lids, bottle caps, etc.) to move beyond the realm of jewelry and into architectural space through installation, while also examining our connections to the material that encroaches on this new space. Similar to Donovan’s approach to setting rules and restrictions to specific materials repeated and juxtaposed upon themselves, Ganch and Kaganovich fully explore a single material’s potential.

While holding a position as an artist in residence at the Lynden Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from 2012 to 2016, Kaganovich created the constantly evolving body of work, Grow. An exercise in collecting, altering, laminating, stitching, and crocheting donated plastic bags, Grow became a personal and community project that required the artist, workshop participants, and viewers to experience the full extent of the material’s capability and existence. The material’s fiction of transforming from plastic bags to a series of floral, bulb-like alien formations with leathery skins changes the viewer’s interaction with the natural and unnatural environment.

In an interview with Susan Cummins for Art Jewelry Forum published in 2013, Kaganovich discussed her interest in the dichotomies of material and object, in how it relates to the viewer’s or wearer’s experience.

I aim to make objects that, through their use, comment on aspects of our existence, our experiences, our interactions, and our bodies. I am interested in function as a point of access for the viewer and an opportunity to create meaning. It’s important that the work is not read as sculpture to be observed, but that it invites the viewer’s participation, whether actual or imagined. It’s through this engagement that the function and implications of each piece are considered.

Grow is a perfect example of how human interaction and perception of materiality ignites a conversation about our impact on the environment. The implications of mass consumerism, waste, and inorganic abundance are addressed in a playful yet startling manner, where this abundance of material clearly has become an organism with new life and agency. With each iteration of the installation, Grow duplicates and extends beyond its previous boundaries of scale and texture.

What initially began as a generative system with a clear point of origin—a large bulb surrounded by smaller forms—is transformed into a rhizomatic system or anti-system with no clear beginning or ending point. Each node is connected to its surrounding blossoms, with new umbilical cord structures that vary through material treatments of crochet, fraying, and lamination of plastic bags. Grow is all-encompassing and unique in every iteration: It’s a life system that each of these objects depends on to sustain its existence.

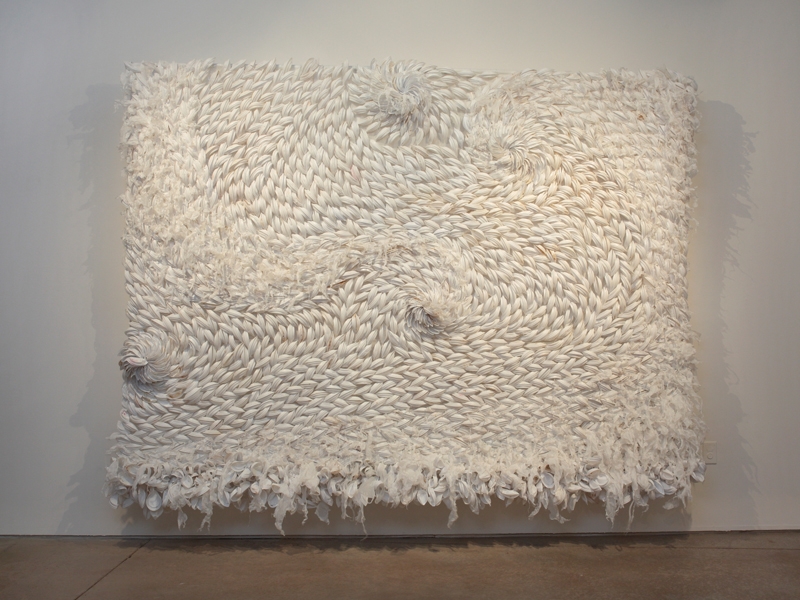

Thus material becomes an entryway and plays a huge part in just how universally approachable the work is for audiences of all ages. Much like in Grow and Donovan’s Untitled, Ganch’s approach to Pile becomes reminiscent of the monumental impact a singular element may have when duplicated on a large scale. The series becomes an easily accessible body of work that asks the viewer to consider material and our understanding of its relation to our existence.

The various iterations of Pile are created from a collection of used plastic bags and Starbucks coffee lids that, when viewed up close, show lipstick marks, coffee stains, and other tells of their previous lives. The pieces serve as delicate, large-scale tapestries that visually engulf the viewer’s attention through texture and pattern.

Ganch’s treatment of the coffee lids is an alluring and unexpected transformation of material. From a distance, the wall pieces look as though they’re woven or made of feather-like textiles, and only upon closer examination does it become apparent that the tapestries are made from plastic lids that have been previously used. These simple objects, which we encounter on a regular basis, become an overwhelming visual collection of our material waste and environmental impact. The materiality of the plastic lids adopts a new form and format from its traditional function. It makes way for a new language that enhances our understanding of what our daily habits can look like. In theory, just one to two days’ worth of sales (and used lid collection) at a Starbucks could create Pile: Starbucks on Robinson. When we consider this fact, the realities of this work becoming a public collaboration further adds to our interaction and experience with the piece.

Pile: Triangle Trade elegantly sits as a traditional tapestry on the walls of the Quirk Hotel and subtly reminds patrons of their material waste in an informal manner. Through the viewer’s engagement with a lid in its original intended use, and then Ganch’s repurposing of the object, this work further shifts our understanding of the material dissonance that traditionally occurs when thinking about “plastic lid” and “fine art.”

With both Ganch’s and Kaganovich’s work, the individual components morph from a functional object to a fiction to a living mythology. These installation pieces not only impact the way audiences view space and material, but also what their use of these materials can become on a monumental scale. Viewers no longer become the passive temporary owners of coffee lids or plastic shopping bags that once existed in the space of “out-of-sight-out-of-mind” garbage land. Instead, Ganch and Kaganovich eloquently remind audiences of their detritus by bringing the material back into architectural space. Pile and Grow become a prompt of the wastelands overtaken by these feral, expansive nonorganisms. We are confronted with the impact that this material has on the environment through the ironic, organic forms that are created through the inorganic and, ultimately, through each artist’s use of material fiction.