Our final Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant finalist interview is with Susie Ganch. Susie, who works in Richmond, Virginia, in the US, is an educator, maker, and passionate advocate for raising awareness about the ongoing need for sustainability of material sourcing, use, and consumption in the field. She’s a co-founder of Radical Jewelry Makeover (RJM). Susie’s infectious belief that collaboratively we can solve problems related to how we value and utilize materials reveals a considered and generous soul. RJM is just one aspect of her practice, and in this interview she unpacks and offers some insights into where RJM is at now.

Vicki Mason: Tell us about your initial training, which saw you earn both a BS in geology as well as an MFA in metalsmithing, and how they led to your establishment of RJM—Radical Jewelry Makeover.

Susie Ganch: Before I started my path in art, I was on my way to becoming a field geologist. My goal had been to explore land for mineral potential, building maps for mining companies. At the end of my education, however, I realized I couldn’t betray our beautiful land by contributing knowledge that would lead to destructive open-pit mining. Jump forward in time, I realized that I ended up doing just that: selling out our land to mining companies! Only now, I had become a consumer of the very minerals I would have been potentially looking for, by using different types of metal and gemstones in my work. Even worse, I was teaching! Which would result in other artists who would go on and do the same thing! I was daunted by the glut of material consumption and waste I saw. I needed a practical way to not only educate myself about material-sourcing issues in my field but also a way to solve problems through making.

RJM is in its 10th year—congratulations! Can you outline how the project has changed, if at all, over this period?

Susie Ganch: The project changes every time we do it. While there are certain parts of the project that happen every time, RJM leaves room for new collaborative ideas to get added into each installment. Sometimes these are permanent additions. For example, RJM Baltimore, our current project, recently had the opening to the culminating exhibition. Some of the facets of the project that the Baltimore collaborators wanted to focus on were the narratives behind the jewelry we collect AND stories behind the jewelry that was donated. While the narrative aspect behind why and what we collect has always been a focus for us, it never surpassed the importance of our environmental message. In Baltimore, it had equal footing throughout the installment. This is just one example of how the bones of the project are set, while the rest of the project is really realized through collaborative decision-making.

The project was originally co-designed by Christina Miller, co-founder of Ethical Metalsmiths, and myself. In 2010, Christina stepped away from RJM in order to focus on her directorship of the organization. This was a huge change for me as Christina was (and still is) such an important collaborator for me. We still work together, and I’m happy she’s still so completely invested in RJM.

Another big change to the project was the addition of the RJM Artist Project. In 2014, I began working with 21 past participants or alumni of the project. I had been interested in cycling back to see if there were lasting effects that the project had had on artists’ studio practices. Some artists I knew had changed their methods of sourcing, others changed the ways they worked, but for others I wasn’t sure. I invited a range of artists from established to emerging (or even still in school). Each person was asked to dive more deeply into the project by creating a broader series of work while writing and documenting their process. I wanted to open up an honest discussion of what it means to have a “wise” studio practice where each artist decides for themselves what it means to do the right thing. In that context are there things an artist won’t do because of environmental or humanitarian concerns? What did these artists think about a sustainable practice?

I sent them a series of questions to guide their writing. With the help of my students, we built a website and posted everything. This project has been ongoing and travels separately from the normal RJM installments. This fall, for example, Deb Lozier’s RJM Artist Project work was included in Metalsmith magazine’s Exhibition in Print. What’s remarkable about the work these artists make is that it transcends a recycled look and seamlessly merges with other innovative relevant jewelry of our time. I’m keen to make sure this project grows and becomes even more visible and vital to our community.

The last significant change to mention is that this past year, RJM Artist Project participant Kathleen Kennedy joined me and is co-directing RJM with me. Since the project generally collaborates with so many people and has so many variables, it’s hard to direct on my own. Kathleen is infusing new energy into our work and has been a great partner.

Have artists’ responses to RJM changed over time? For example, have the sorts of works being produced changed, perhaps? Have any artists you’ve worked with completely shifted their practices toward addressing the key issues underpinning the project so they are now making completely different work since being involved? Some stories would be great to hear.

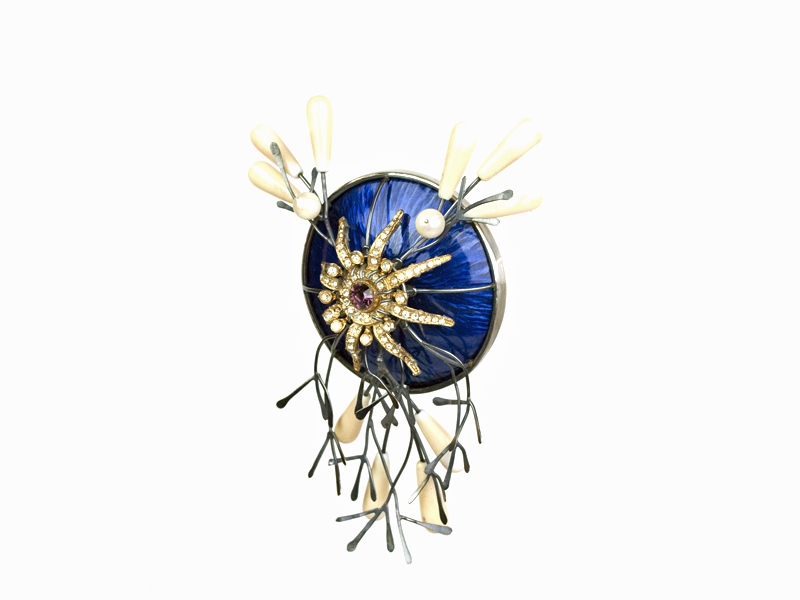

Susie Ganch: All of the work made in RJM responds to trends within the field because of what’s donated. This has been an interesting aspect of the project because one of our motivations is to make “unwanted” jewelry into new vital pieces that are wanted. So how do you turn a dated look into one that’s fresh? Likewise, how do you impose your own aesthetic sense onto raw material that already has a look? It’s challenging, for sure. Add to that mix of challenges the fact that we invite everyone to participate, from beginning jewelry students to seasoned professionals, and you can understand how we see a range of finished work that reflects these variables. Some jewelers are naturally drawn to this way of working. For instance, Robin Kranitzky and Kim Overstreet made a brooch (for RJM RVA, in 2014) that reflected their style so effortlessly! I love this brooch because it played to the strength of the materials AND the artists.

Some artists HAVE changed the way they work after participating in RJM. One person I think about is Curtis Arima. Curtis is a professor at CCA and I’ve admired his work from the beginning of his career, when I saw his graduate work from Cranbrook. You can imagine how inspired I was when he confessed to me that RJM had made him rethink his practice, what he makes, and how he makes it. His RJM Artist Project jewelry really reflects that. He has the ability to transform “unwanted” jewelry into timeless jewelry. In my mind, timeless jewelry is one of the highest goals because it means that the piece of adornment doesn’t lose its relevance and can be passed on for generations. In a small way, it solves the need for more materials that can replace the irrelevant piece.

Some artists have more easily shifted their thinking (in terms of the issues) by joining and working with Ethical Metalsmiths. Kathleen Kennedy is a great example of this. She was in the first installment of the project and has been an RJM Artist Project participant and is now helping me by co-directing. Lucy Derickson, Kelley Morrison, and Brian Fleetwood have done the same. I met Brian during the RJM NM project when he was a student at IAIA. He came and did his MFA at VCU at the same time Lucy and Kelley were there. To satisfy their need to join, participate, and make a difference, they formed the Ethical Metalsmiths Student Committee, which continues to grow. They have an annual exhibition, So Fresh So Clean, which seeks to highlight work in this vein being made by students while inviting a conversation that reveals complexities young jewelers face when thinking about sustainability, the materials we use, how we use them, ethics, AND the personal aesthetic and conceptual agendas we all bring with us when we enter the studio. I’m so proud of these emerging artists for their dedication to seek, find, and celebrate new ways to consider jewelry.

What happens to the jewelry/excess materials that are left over at the end of an RJM project/collaboration?

Susie Ganch: The easy answer is that they all end up in my basement! We receive about 100 pounds of jewelry at each installment, and only a percentage is used. At first this really troubled me because I thought the glut was overwhelming. What I’ve come to realize is that the amount we receive is necessary! Participants need to “mine” this material for what they think has potential. It’s an important part of the process and it reveals the differences between throwaway materials and materials with re-use potential!

Just so you don’t think my basement has a hoard of jewelry in it that accumulates with each project, I can report that RJM uses the material for the RJM Artist Project as well as offshoot projects and other educational opportunities. For instance, I’ve supplied RJM materials to after-school programs at the Visual Art Center of Richmond.

You recently developed an RJM teaching “tool kit.” What is in this tool kit, and how does it work?

Susie Ganch: The tool kit has almost everything a school needs to organize an RJM installment on their own. It breaks the project down into steps that can be followed folder by labeled folder. In truth, an institution doesn’t really need Kathleen or I to help them at all (if they don’t want). They can join Ethical Metalsmiths, as an institutional member, request the kit, and do it. That said, I’ve noticed that when I visit a school and help kick off the installment, it helps to frame the project in broader terms that help participants understand the mission of RJM. My job is to tie what participants are doing to the broader conversation outside of their classroom and studio. I want to make sure they know that by collaborating in their installment, they are joining the conversation of a BIG community of like-minded individuals searching for ways to do things better, and in a way that doesn’t cause harm. That’s a tall order, but at the foundation of my belief is the idea that we are all smart individuals. Collaboratively we can solve anything if we try. My job is also to make sure that the hard facts about mining and the complexities of what it means to make jewelry is being addressed in some way alongside the collaboration and fun nature of re-using stuff.

Your proposal for the Susan Beech award saw you propose creating a catalogue book and video with commissioned essays in honor of RJM’s 10 years. Will you go ahead with this project?

Susie Ganch: I’m a bit superstitious and don’t want to say anything definitively. However, I’m keen to see this through!

Your RJM collaborations have taken you into jewelry communities outside the institutions associated with contemporary jewelry. I’m thinking of your projects with Native American communities and so forth. Can you speak to your learnings from these encounters?

Susie Ganch: We have mostly worked within jewelry communities, including the Native American jewelry community in NM to which you are referring. The easy answer is every community I’ve worked with has taught me valuable things that have shaped me into the artist and person I am today. Each community I work with is different and unique because we are all different and unique. Threads of similarities are woven between all of the collaborative groups I’ve been with, which shifts my perspective to thinking of us as one big community. However, there are always discoveries I love to learn in the differences in ways of thinking, themes, values, and communication, among others.

Where do you see RJM in 10 years’ time?

Susie Ganch: Ideally, RJM won’t be around in 10 years because it will have served its purpose!

Along with RJM, you teach and have an independent studio practice. Tell us how RJM has influenced how you view and use materials in your own studio work. Do you use only new/virgin materials or just recycled and up-cycled materials, or a combination of both? Does it depend on the brief?

Susie Ganch: Working collaboratively with RJM has really brought deeper meaning to my independent studio practice. It forces me to consider the projects I take on, the materials and techniques I use to make the work, as well as the broader ideas driving my practice. Ideally, I would only re-use materials, but this is a constant negotiation that I have to debate. Is the idea more important than the broader implications of the work? When is it worth it and when isn’t it? I don’t have a formula or a right answer but that’s why I keep trying to find solutions by making and working with Ethical Metalsmiths. I believe participating, succeeding, and failing are the only ways to find answers. Lately, I’m really thinking about what will remain after I’m gone. I want the materials I’ve used in my work to be ready for re-use in the future if what I’ve made isn’t timeless. OR I want it to disintegrate and make room for new ideas.

Can you tell us about the last piece of jewelry you made?

Susie Ganch: I’m making a piece right now for an exhibition titled Ripple Effect, which will open at the ECU metal symposium in January. Artists were partnered and asked to swap materials in order to foster collaboration. My partner, Mi-Sook Hur, sent me two beautiful enameled pieces with delicate feathers drawn on them. I measured the knuckles and fingers of my hands to make my own “feathers” for the piece. I’m wondering how many of my feathers I need in order to fly? I’m considering the wonder and futility of flight, my desire and my limitation. My feathers are from steel wire that will rust and disintegrate over time, leaving behind the feathers that can really do what mine can only dream of.

What are you working on now?

Susie Ganch: Last fall I completed a residency in the Kohler Arts/Industry program in the pottery foundry. My proposal was to make parts for pieces that would be completed in my studio. It was difficult for me to consider making pieces out of a singular material, and knew I would need time to use what I made for mixed-material sculptures. While there, I worked with Kohler’s cull: toilets, sinks, and urinals that were removed from production because of defects resulting from the production process. Every day, I went digging through dumpsters and bins collecting defective green-ware to make into components for future sculptures. Upon returning to my studio, I converted my space into a steel fabrication shop, taught myself how to weld (thank you, Hoss Haley and the university of YouTube!), dusted off my lathe and slip roller, and got to work. I just finished a nine-foot column comprised of cut-up pipes that move effluent and water in toilets, urinals, and sinks. The bricks of vitreous ceramics were strewn with cracks that I repaired using a quasi-Kinsuke technique that invites an up-close look, while the piece also satisfies my eyes with its large scale. As a jeweler, I’m intrigued both by detail and an intimate view of something, as well as by how I use space and surrounding architecture. This shift in my practice has been challenging and very satisfying.

Can you recommend some book titles for those interested in diving deeper into the topics underpinning RJM philosophies?

Susie Ganch: I confess that I look to certain websites to inform myself on the topics underpinning my work with RJM and Ethical Metalsmiths. While I love books, we’re talking about topics that are evolving and changing at a rapid pace that a book can’t easily capture. I’ll list some sites that people can use to inform themselves below.

That said, there are a few things to mention that influenced me early on during my career and working on RJM. One book that was pivotal to my thinking was written by William McDonough and Michael Braungart and is titled Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. A documentary that was central for me was Our Land Our Life. This film is no longer available, but there’s an abridged version that still is effective at framing the issues on a human level, titled American Outrage. I still use this video as a learning tool, though it’s quite old, because the battle is still being fought and students can get an understanding of where we are now versus 10 years ago. It invites discourse in my classrooms that is essential to what we do. Of course, everyone in our field should have read Susan Kingsley’s seminal article in Metalsmith magazine titled “The Price of Gold.” Susan changed my life with that article, and having the chance to work with her in Ethical Metalsmiths was an honor.

RESOURCE LIST

Here are some sites that readers might find helpful to get started (this is just a beginning, there are more):

Alliance for Responsible Mining: http://www.responsiblemines.org/en/

Jewelry Industry Summit: http://www.jewelryindustrysummit.com/

Pure Earth: http://www.pureearth.org/

The Enough Project: https://enoughproject.org/

Earthworks: https://www.earthworksaction.org/

Responsible Jewellery Council: https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/

Fair Jewellery Action: http://www.fairjewelry.org/

Swiss Better Gold Association: http://www.swissbettergold.ch/en/home

Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance: http://www.responsiblemining.net/

Monica Stephenson’s blog, idazzle: http://idazzle.com/?s=sustainable+jewelry

The Dragonfly Initiative: https://thedragonflyinitiative.com/

Cradle to Cradle: http://www.c2ccertified.org/

Of course, Ethical Metalsmiths: http://www.ethicalmetalsmiths.org/ (our new website is just around the corner!)

Ethical Metalsmiths Student Committee site: https://emstudents.org/ (where you can view the past So Fresh So Clean exhibitions and see what is evolving in the minds of students who are entering the field.)

Radical Jewelry Makeover: http://radicaljewelrymakeover.org/home.html