Also in this series:

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Demetri Broxton’s Beaded Boxing Gloves

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Angela Hennessy

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Hollis Chitto

This is the third article in a series focused on artists whose work is adjacent to jewelry. For my purposes, jewelry-adjacent artists use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field.

Monica Canilao[1] is a mixed-media artist who works with cast-off and abandoned objects. She collects and archives these objects as mementos of the displaced and forgotten people and places our culture leaves behind in its constant march toward the future. Her practice is uncontained and fluid, difficult to define beyond the found objects that are central to her work.

She completed her bachelor’s degree at California College of the Arts, when it was still California College of the Arts and Crafts, in the Bay Area. Though she began her formal studies with a focus on painting she switched to illustration after being inspired by educator and illustrator Barron Storey. Her drawings and illustrations continue to fuel her work; however, she doesn’t limit herself to a single medium or material. One day, she might be working on a mixed media painting, the next stitching an elaborate costume, then later experimenting with fabric and architectural installations. Through it all, recycling and utilizing found objects drive her creative process.

“The things I’m most attracted to have already had a life. They are special and unique, made by hand and with care; you may never find them again. The things I prefer to use are often discarded, gifted, or found in abandoned buildings.” —Monica Canilao[2]

She feels connected to these objects. Referring to herself as a “useful hoarder,” Canilao keeps her studios full to bursting with objects that span culture, time, and place. She methodically organizes the pieces and can identify every object. Each piece holds Canilao’s memory of finding it: where she was, who she was with, and the circumstances of the discovery. This is in addition to the individual history of the object itself. She refers to her archive of objects as “a visual journal.”

Canilao loves the “weird broken things” [3] she collects. An avid flea-market devotee, thrift-store scavenger, and antique obsessive, she strongly believes in the reuse, repair, and recycling of everyday objects. She doesn’t believe new things have more value than old things, and finds fast fashion and disposable, single-use, and mass-produced items particularly distasteful. Through her work, she honors the time when things were made to last and, as caretaker of the objects she finds, gives them new life through her art.

She takes old jewelry apart and makes new pieces, reflecting the principles of Radical Jewelry Makeover, which “link recycling, reuse, and collaborative work sessions with the creation of unique, innovative, handmade jewelry.”[4] Both RJM’s projects and Canilao’s practice are reactions against rampant consumerism and waste. Many jewelry artists embrace recycling and reuse as a way of creating new jewelry, mining society’s waste for useable materials, including Erica Bello,[5] who crushes Mardi Gras beads for her brooches, and Jina Seo,[6] who repurposes worn-out leather gloves.

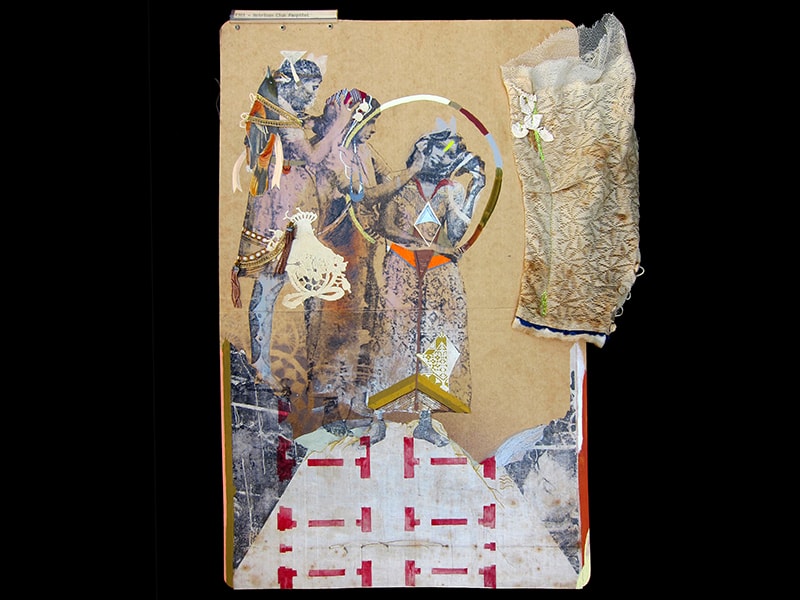

Mixed-media assemblage is another way Canilao creates purpose for her treasure trove of objects. She groups objects together: lace doilies, strings of pearls, curtain rings, bric-a-brac, illustrations from magazines and books, architectural elements like knobs and hinges, keys, washers, domestic items like broken spoons, wooden spools, and darning needles, etc. to create wall pieces. The final pieces are textural feasts that make the viewer hungry to identify the component parts.

Her assemblages include strange and macabre objects like horse ribs and goat hooves. There’s a collection of combs and toothbrushes picked up on Dead Horse Bay (a stretch of shoreline near an old landfill in New York) paired with recognizable domestic objects like hair rollers and lace from an abandoned hoarder house in Detroit. The colors are often muted, reflecting the muddy browns, mauves, and taupes of aging objects. She doesn’t remove the patina of time or mitigate the fading effect of age and sun. Instead, she combines the aging objects with splashes of brighter color through interventions with thread, paint, and new paper. The pieces become a layered archive of memories—her memory and the object’s memory—merged to create a new narrative.

In her Portrait series, a reclaimed formal vintage photograph is the starting point for each piece. Canilao finds these black and white portraits in abandoned houses and in flea markets or receives them from family members far removed from the depicted ancestor. The figures are formally posed and stiff with the stillness required of late 19th-century photographic technology. To the modern eye well-versed in the ease of a selfie, the photographs read as eerie.

“In such a picture, that spark has, as it were, burned through the person in the image with reality, finding the indiscernible place in the condition of that long past minute where the future is nesting, even today, so eloquently that we looking back can discover it.”[7] —Walter Benjamin

Formally staged portrait photography[8] was a sign of wealth in the early 19th century. In the American context, this wealth was derived, directly or indirectly, from settler and colonial activities. For Canilao, the act of taking the found portrait of a forgotten figure and surrounding the individual with objects that stretch into futures that person couldn’t have imagined shifts their context. Her reimagined narratives don’t prioritize the portrait sitter’s frame of reference. Her fantastical embellishments transform them, creating new storylines full of possibilities.

She alters the photograph itself, embroidering designs directly onto the photographic paper; adding color to the face with ink, acrylic paint, gouache, or even nail polish; or partially obscuring the image by layering other objects over it. Illustrations and other works on paper from various cultures, part of the detritus Canilao salvages, merge with items from her personal archive with a few stitches of thread. Additional objects are bound securely using thread, wire, or adhesive. The stitches and wrapping are incorporated into the final piece, adding visual interest while they hold everything together.

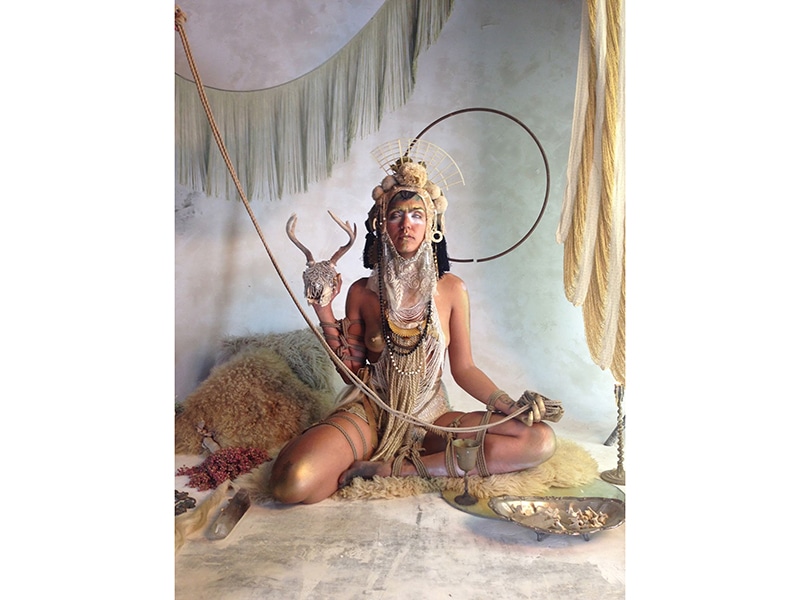

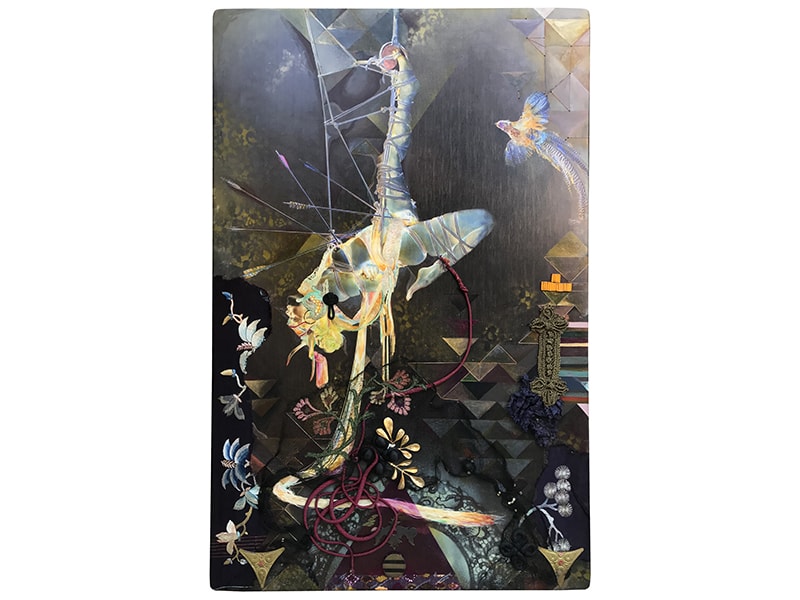

In a series of larger-scaled mixed-media paintings, she adds handmade lace, antique beadwork, found textile, and other remnants directly onto the surface or sewn into the wood panel. This project began as a collaborative photographic series with photographer Marcus Gulliard, artists Trueblue and Therin Brooks, stylist Jessy Brown, and shibari rigger Kanso (shibari is the Japanese practice of rope bondage). The colors are more vibrant in this piece than in the wall hangings from the Portrait series, awash in watery blues and purples. The domestic circular geometry of the tatted doily patterns contrasts with the rigid severity of the shibari ropes suspending the central figure.

Canilao allows no delineation between what she makes and how she lives. Her home, a ramshackle 1890s Victorian in Oakland, CA, is an ongoing art project inside and out. She preserves the echoes of previous lives lived within its walls, including architectural features like the vintage hardware and aging wallpaper. The preservation extends beyond the structure of the home. Canilao restores and adds to its history captured in posters, newspapers, and magazine pages that make up a collage which started in the 60s and 70s and covers every square inch of the entryway, walls, ceilings, and upstairs of the house.

Canilao’s family is supportive of her way of life. While her father is a carpenter and immigrated to America from the Philippines after fleeing unrest under President Marcos, her maternal family has deep roots in the Bay Area, going back to the 1800s. Her grandfather on her mother’s side was an architect. Her mother went to school for art, massage, and horticulture, and has always been her biggest supporter. Her grandmother was a sharp dresser who loved to receive guests and often wore flowers in her hair. Canilao also utilizes ornamentation, large jewelry pieces, and elaborate outfits as a daily ritual. She combines these elements to form a greater connection to her past, embracing her artistic vision in aspects of her life.

“From boats to portraits, everything I make I use to reimagine the meaning of home, the power of collectivity, and the imprint history has left on me. My community and collaborators, my roots and their nearly lost traditions, my neighborhood and its trash piles are all integral, necessary parts of my life and art.”[9] —Monica Canilao

She has an affinity for bringing people together. This impulse connects both sides of her family lineages—her paternal family through the Filipino ideal of bayanihan, which values collective mutual aid and assistance,[10] and her maternal family, specifically her grandmother’s love of hosting and feeding people. Partially because of this, she considers the formality of most traditional gallery spaces limiting. It has always been important for her work to be welcoming to those who might be uncomfortable in the typical, white-walled gallery setting. The art Canilao makes is social and touchable, immersive, a starting place for conversations, so the environment needs to reflect that. She invites people to engage with the work and share their own experience of the objects through conversation with her and others in attendance.

Occasionally, Canilao teaches art classes and workshops to encourage kids and adults to make things with the objects that surround them. She loves showing kids how to use things like spray paint, sewing machines, and power tools to not only fix and build things, but to feel confident they can do things themselves. Ideally, she prefers to teach kids before culture instills the restraints of gender roles, empowering them to try and see if they like it without preconceived ideas of what is “appropriate.” She believes everyone should know how to mend things as an alternative to the landfill.

“The common thread lacing her diverse range of work is utilizing found and recycled materials to draw attention to our careless culture that casts things aside and teaching the viewer, participants & students if we practice the art of maintenance our world would look much different.”[11] —Monica Canilao

With roots in the DIY culture of punk,[12] Canilao sees skill-sharing and collaboration as central to her practice. No one person has all the knowledge, so collaboration breeds surprise and innovation. For Canilao and most artists, it requires a practice of letting go of control to allow the unexpected to happen. Through collaboration, she builds strong relationships by creating alongside other artists in their shared passion for art-making. A few past collaborators include Swoon,[13] Xara Thustra,[14] and Lauren Napolitano.[15]

Canilao’s art practice reaches every aspect of her life. It is sustaining, generative, and deeply connected to her environment and community. Although as a mixed-media artist her work is constantly shifting and transforming, themes in her work begin to emerge. Evident throughout is her reverence in handling the material, the collaborative way of working with the objects and within her community, and the composition of objects, merging effortlessly to create something beautiful and enduring. Canilao’s work connects the bygone and the present, and the individual of the now with the consciousness of the past, to manifest a shared future that reaches out from the objects we leave behind.

Note: Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History is hosting Monica Canilao and Xara Thustra, collaboratively known as MCXT, for a residency in Fall 2022. For a new art festival called Common Grounds, they’ll research the period when the town was known as the “Florence of the West” and reimagine the waterways, floats, and festivals that once entertained the town.

[1] See more of Monica Canilao’s work at http://monicacanilao.com, @__moreferalthan__, Wewillallbewelll.com, @we_will_all_be_well

[2] From a recorded interview with the artist, December 15, 2021.

[3] From a recorded interview with the artist, December 15, 2021.

[4] For more information about Radical Jewelry Makeover, go to https://www.radicaljewelrymakeover.org/ or listen to an interview with one of RJM’s directors, Kathleen Kennedy, about the organization’s work in Boston and Brazil at https://artjewelryforum.org/interviews/ajf-live-with-rjm-brazil-and-boston.

[5] https://www.radicaljewelrymakeover.org/erica-bello.

[6] https://www.radicaljewelrymakeover.org/jina-seo.

[7] Walter Benjamin, “Short History of Photography,” Literärische Welt, Berlin, 1931, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.artforum.com/print/197702/walter-benjamin-s-short-history-of-photography-36010.

[8] For a brief history of early portrait photography, visit https://notquiteinfocus.com/2014/10/16/a-brief-history-of-photography-part-11-early-portrait-photography/.

[9] From Canilao’s artist statement, accessed 1/24/2022 at http://monicacanilao.com/about.

[10] Frolian Rivera, “Filipino Bayanihan: Towards a National Value Formation,” graduate thesis, https://www.academia.edu/50197052/Filipino_Bayanihan_Towards_a_National_Value_Formation.

[11] Monica Canilao’s artist statement on the US Department of State website, accessed on January 13, 2022, https://art.state.gov/personnel/monica_canilao/.

[12] Ian P. Moran, “Punk: The Do-It-Yourself Subculture,” https://westcollections.wcsu.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12945/2257/2010_moran.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

[13] Swoon’s website: https://swoonstudio.org. Canilao and Swoon’s collaborative page: http://monicacanilao.com/art-collaborations/new.

[14] Xara Thustra’s website: https://xarathustra.com. Canilao and Thustra’s collaborative page: http://monicacanilao.com/art-collaborations/xara-thustra-mcxt/.

[15] Lauren Napolitano’s personal website: http://laurenapolitano.com/. Canilao and Napolitano’s collaborative page: http://monicacanilao.com/art-collaborations/lauren-napolitano.