This is the first article in a series focused on artists whose work is adjacent to jewelry. For my purposes, jewelry-adjacent artists use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field.

Boxing is an arena where legends are made, teeth-shattering violence is celebrated, and hypermasculinity is normalized. It is also a highly racialized space, where Black men dominate and simultaneously put on display. So why would a bead artist who has never boxed create art about boxing?

Demetri Broxton[1] is a mixed media artist of Louisiana Creole and Filipino heritage, born, raised, and currently residing in Oakland, CA. He uses beadwork to embellish boxing gloves, covering their surfaces with cowrie shells and glass beads. Broxton uses the cultural histories of these materials to draw parallels between history and current culture, positioning his work in the imaginary divide between craft and fine art.

Having started as an oil painter, Broxton found it impractical to carve out dedicated studio time after the birth of his second child. At the time, he didn’t want to abandon his creative impulse, so he asked his mother to teach him knitting, then tatting, then tatting with beads, which brought him to Blue Door Beads[2] in Oakland. There, he found a supportive community of the bead obsessed. He started weaving beaded jewelry—nothing too complicated, but delightful, wearable, and accessible—learning techniques from a book on traditional Native American beading patterns. He quickly discovered the public was reluctant to pay for laborious hand-beaded jewelry, a familiar dilemma to many in the craft world. Through his network, he connected with Patricia Sweetow, a San Francisco-based gallerist with an interest in artists who “mine the rich, multifaceted traditions of craft, in ways that embrace diverse cultural origins and conceptually nuanced discourse.”[3]

With Sweetow’s encouragement, Broxton began working on a project that he’d been contemplating, most likely as he sat for hours beading pairs of earrings. He searched the internet for male-bodied beaders for camaraderie and to ground his work in his personal experience. Through Instagram, he connected with BigChief Demond Melancon,[4] who works within the Mardi Gras Indian tradition in New Orleans. Melancon shared videos showing his techniques and provided encouragement as Broxton began working at a larger scale. As his stitch work evolved and he developed his own patterns, Broxton had the base he needed to launch a project that combined three major interests: the transatlantic slave trade, hip-hop, and boxing.

Cowrie shells and the transatlantic slave trade

Broxton’s piece Worth the Weight uses a combination of cowrie shells and glass beads to embellish a pair of Everlast boxing gloves, “the preeminent brand in boxing since 1910,” according to the company’s website. Long strands of cowrie shells extend from the gloves, pooling on the floor or pedestal when displayed. Text woven with glass beads on the gloves is both the title and a reference to a method of financial accounting during the transatlantic slave trade, when cowrie shells were used as currency.[5] Broxton grounds his use of cowrie shells in research from Saidiya Hartman’s 2007 memoir Lose Your Mother. As Hartman traces the slave routes, her research reveals that roughly one pound of cowrie shells purchased 13 pounds of a person sold into slavery. In Worth the Weight, the amount of cowrie shells Broxton incorporates is equivalent to the purchase price, in weight, of a modern heavyweight boxer, had that man been sold into slavery some 400 years ago. Broxton’s use of cowrie shells in this way connects two different periods—the transatlantic slave trade and the modern boxing era—through a looping of material, data, and time that reiterates the non-linearity of history and the ability of one material to relate multiple meanings.

The way Broxton applies the cowrie shells to the surface of the gloves also refers to the Yorùbá tradition of the Ilé Ori.[6] These ritual objects were traditionally covered with cowrie shells and were shrines that housed and protected an individual’s head or orí, the seat of a person’s character, behavior, and ultimate life destiny.[7] The Yorùbá believed these objects of wealth and status provided a level of protection for the owner from Portuguese slave traders. Broxton’s gloves draw several parallels to these ritual objects, first in the material choice, second in the appearance of the finished object, and third in the way that the gloves protect the boxer’s hands, bringing wealth and prestige if the wearer is successful in the ring, as well as a modicum of protection from white society.

The transatlantic slave trade started roughly in the 1450s and continued for over 250 years and, during that time, cowrie shells went from being a currency of significant value to being worthless. Today, both jewelry and ritual objects tend to be made of materials that are expected to retain value and appreciate over time: gold, silver, platinum. Several contemporary jewelry artists play with concepts of value by using currency as material, including Katrine Borup[8] and Lauren Tickle.[9] That Broxton’s materials were once valuable enough to trade for a human life and now can be purchased for pennies provides a different perspective on the concept of material value, let alone the questionable morality and cultural norms that made the transatlantic slave trade possible.

Glass beads and hip-hop

Broxton often titles his pieces with phrases from hip-hop or rap lyrics. For example, Worth the Weight is also the title to the first track in Nigerian-American musician Jidenna’s 2019 album 85 to Africa,[10] an album described as “a trip through the African diaspora that verges on sonic cinema.”[11] Broxton beads the text onto the boxing gloves using Czech or Japanese glass beads. Czech glass beads were introduced as trade goods to the indigenous people of North America and Africa by European colonialists and slave traders, respectively. The new material was quickly absorbed into traditional methods of making in both cases, taking on new meanings within different cultures.

Broxton researched how the Yorùbá incorporated beads into their material language, specifically how artisans selected the colors of the beads for the embellishment of clothing, everyday items, and ritual objects. Yorùbá color theory includes three color groupings: funfun (white, gray), pupa (red, pink), and dudu (black, green). Each grouping includes different associations with temperature, with funfun representing coolness, pupa representing heat, and dudu bridging the spectrum. The color groupings also contain personalities. For example funfun is wise and calm, while pupa is quick to anger and reactionary, as well as having connections to deities, ancestors, and healing properties. Within the context of beading, the selected colors are more than a visually pleasing composition. They communicate complex messages about power, status, protection, and cultural beliefs.

Video courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery

The video above includes a sample of the song “Money,” by Cardi B, playing as the video pans over Broxton’s I Was Born to FLEX. The video highlights the intricacy of the surface beading and shows the incorporation of other materials, including chains, bullets, glass gems, and leather pouches containing herbs, roots, and essential oils. The colors of the glass beads Broxton selects to weave the text are influenced by his knowledge of Yorùbá color theory and inspired by the lyrics of Cardi B’s track “Money”—a frank discussion of money, wealth, and power.[12] Broxton’s mashup of the culturally coded language of hip-hop and the symbolic language of beads provides different entry points for viewers to engage with his work.

Contemporary jewelers often use beads to add color, light, and materiality to create beautiful pieces. German jeweler Axel Russmeyer[13] comes to mind as a meta beader, using tiny seed beads and antique beads to make larger beads that are juicy, luscious, and mind-blowingly complex. French jeweler Jacqueline Lillie,[14] who is based in Austria, is another well-known jeweler who makes gorgeous, flexible, and wearable compositions of tiny glass beads, reminiscent of textiles in their behavior and surface patterning. Broxton’s layering of different meanings through the use of color and the incorporation of already powerful lyrics adds complexity to the use of the glass beads, without detracting from their beauty or the visual interest of the finished object.

Boxing gloves and boxing mythologies

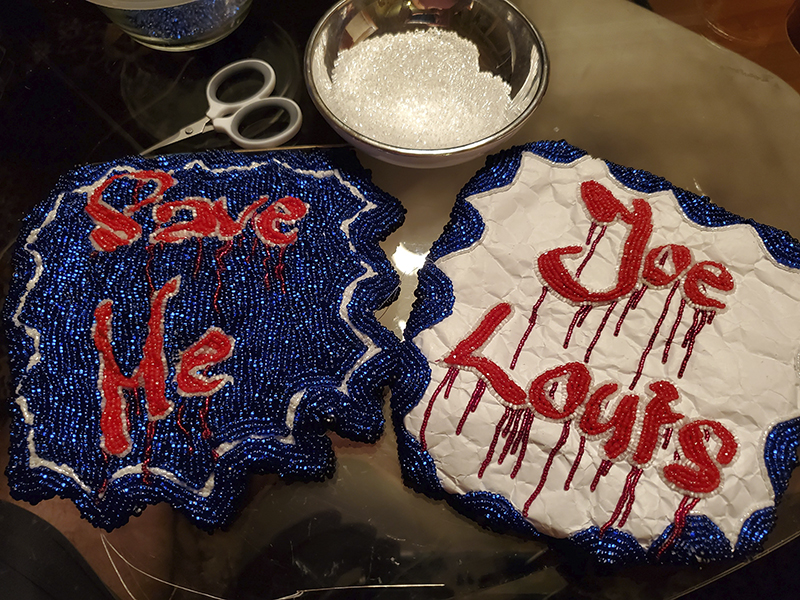

The final material in Broxton’s work, clearly evident throughout all these pieces, is his core material, the boxing glove. The title of the piece Save Me, Joe Louis comes from an apocryphal story of a death row inmate in the 1930s crying out for prize boxer Joe Louis in his final moments.[15] This story shows the tension between a hypersensationalized otherworldliness achieved by an elite few through sports and the lack of dignity afforded to the average Black citizen, specifically during the Civil Rights era, where the story is positioned. The video below includes a voice-over of Broxton explaining the piece, interspersed with archival images and detailed closeups of the beadwork.

Video courtesy of Patricia Sweetow Gallery

When looking at wearable objects that require the body to be activated, viewers use their imaginations to fill in the absence of the body. In Broxton’s case, the gloves conjure the fists, the muscled forearms, the broad shoulders, and the brutal full-bodied dance of a boxer. The objects themselves are heavy with cowrie shells and verge on shapelessness, almost losing the legibility of the boxing gloves, though the Everlast label remains readable. The gloves aren’t wearable, not even temporarily, since Broxton has stuffed the gloves with herbs to maintain the glove form. These pieces aren’t decorated to be used; they have become something else entirely. Their functionality is lost.

So, what attracted Broxton to the boxing glove as an artistic form? His grandfather was a boxer for the US Army—a not-so-distant family member is often a classic start to many American craft stories. And, while Broxton was never a boxer himself, he didn’t avoid the rite of passage that demanded a fight or two to prove he wasn’t a “punk.” These two personal connections made the legacies of American boxers Peter Jackson (“The Black Prince,”1861–1901), Joe Louis (“The Brown Bomber,” 1914–1981), and Muhammed Ali (“The Greatest,” 1942–2016) very real to Broxton. All three of these boxers used their success in the ring to accomplish great things in the world and were inspirational figures to successive generations of young men. When Broxton found himself dreaming of larger projects, he reached for materials he had on hand: a pair of dusty boxing gloves, a surplus of beads from his early jewelry projects, and an interest in Black culture in America.

As the project unfolded, Broxton discovered both boxing and beading merged stereotypical masculine and feminine characteristics. The delicacy of the footwork in boxing is as important as the force of the punch. And the heroes of his childhood strove to balance the in-the-ring brutality with an elegance that matched their prosperity outside the ring. Beads had a similar merging of delicacy and brutality in their use as a culturally rich, decorative embellishment as well as blood money in the slave trade. Broxton underlines the brutal history of glass beads by weaving brilliant red glass beads dripping like blood from the text sections of his work.

The identity of bead artists also provided tension for Broxton to explore. In an American and European context, women performed the time-consuming and tedious bead work, while in the Yorùbá and Mardi Gras Indian context, men did. Broxton’s evolution as a beader involved the research of other male-bodied bead artists, specifically to reconstruct and question the concepts of masculinity, decoration, and power within culture. The tension between masculine and feminine, the ideals of beauty and who defines it, and the ways power and freedom are accessed, and by who, loop throughout his work, creating a labyrinth of connections across centuries and cultures.

Broxton’s work combines archival data with modern culture, interspersed with sports and academic references while using material heavy with history, all of which can be dizzying to take in at once. The method of making the pieces, though, is rather plodding. Broxton uses a brick stitch to build the pieces, one bead at a time, in a linear, time-consuming fashion. Perhaps it is the time it takes Broxton to complete a piece that allows him to engage with the labyrinth of history that brings new connections at every turn and instills his work with an abundance meaning. Or maybe history is that complex, layered, and interconnected. Regardless, the pieces are what the viewer sees first, before understanding the history: the seduction of the beads, the punch of the text, and the physical presence of the objects. Each of the layers provides an entry point. Perhaps the boxing gloves are seen first and the viewer wonders why, or the Cardi B reference makes someone do a double take, or the colorful, intricate beading requires a closer look. Then, once viewers are hooked, the decoding of the messages held within the material and the layering of history pulls them in deeper, as deep as they are willing to go.

References

Henry John Drewal, “Yorùbá Beadwork in Africa,” African Arts 31, no. 1 (1998): 18–94. JSTOR. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Rebekah Frank, Demetri Broxton, and matt lambert, “Queering Masculinities,” New York City Jewelry Week, panel discussion, recorded Nov. 15, 2020.

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).

Olatunji Ojo, “The Organization of the Atlantic Slave Trade in Yorùbáland, Ca.1777 to Ca.1856,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 41, no. 1 (2008): 77–100. JSTOR. Accessed Feb. 15, 2021.

William Wilson, “‘Beads’ Lights Culture of the Yorùbá,” Los Angeles Times, April 1, 1998. Accessed Jan. 26, 2021.

[1] Demetri Broxton: https://www.instagram.com/dbroxtonstudio.

[2] Blue Door Beads: http://bluedoorbeads.com.

[3] Patricia Sweetow Gallery: https://www.patriciasweetowgallery.com.

[4] BigChief Demond Melancon: Instagram + BBC’s In The Studio.

[5] Cowrie shells were used as a standard currency in West Africa for centuries, both by Africans and Europeans. Even though they no longer serve as money, they’ve been woven into the culture, both symbolically and ritually. Learn more about this history here.

[6] The llé Ori pictured here is from San Francisco’s de Young Museum. To hear Natasha Becker, de Young’s Curator of African Art, speak with Dan Hicks, author of the book The Brutish Museum, about the complexity of western museums holding African ritual objects as part of a larger conversation, visit this link.

[7] Adenike Cosgrove, Ile Ori (House of the Head Shrine), ÌMỌ̀ DÁRA. Accessed February 4, 2021.

[8] Katrine Borup’s power-flower.

[10] Jidenna’s music video for “Worth the Weight,” from the album 85 to Africa.

[11] Jenni Moore, “Jidenna’s 85 to Africa Is a Trippy Jaunt Through the African Diaspora,” The Stranger, September 26, 2019. The Stranger. Accessed February 4, 2021.

[15] David Margolick, “Save me Joe Louis!,” L.A. Times, November 7, 2005. Accessed February 9, 2021.