When she began this article, Rebekah sent out a survey to AJF members and the online AJF community. Thanks to everyone who participated—the information offered in the responses helped shape the direction of this essay.

You’ve fallen in love with the world of art jewelry, you’ve met jewelry artists at fairs and gallery openings, perhaps even visited their studios, and you’ve purchased some incredible pieces that spoke to you. Maybe you have 10 pieces or, perhaps now that you think about it, you have more pieces than you realized. Whether you think of yourself as a “collector” or not, it’s time to consider how you’re now part of these objects’ stories.

REASONS TO CATALOG YOUR JEWELRY

There are many reasons to catalogue your pieces, the first being it shows respect for the work of the talented artists who made the jewelry you love. It also honors your burgeoning interest and expertise in this niche artistic field. Plus, it helps to have what you own and by whom it was made written down, so you’re not forced to rely on memory. As you accumulate more pieces, chances are you’ll forget the strange material in that one necklace, or the spelling of the name of that artist from Estonia … or was it Belarus? Wait … Iowa?

Another reason to create an organized record of your art jewelry pieces is in the event of catastrophic loss. While I was the director of AJF, I received requests from people after floods and fires seeking information about pieces that had been lost or damaged. Having detailed information about your pieces, including contact information for the artists and the galleries you purchased them from, can help in these difficult times, whether for insurance purposes or to garner advice for replacement and repair.

Or you may find yourself in the position of lending or gifting one or more of your pieces to a museum, whether for a short-term exhibition loan or to add to their permanent collection. It helps a museum immensely to be presented with an itemized list of the pieces, including material, value, bios, etc., along with images and other ephemera related to the piece.

“When a collection LACMA is considering for acquisition comes with detailed documentation, we curators rejoice because it makes the process so much easier.”

—Bobbye Tigerman, Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross Curator, Decorative Arts and Design, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

If, heaven forbid, you were to become incapacitated in some way, all the work you’ve put into loving these pieces of art would be in vain without a detailed catalog. Stories about beautiful pieces of significant historic value ending up in thrift stores abound in the art world, and you’ve put too much work and love into your collection to allow that to happen. Leaving a catalog makes it easier on the people who come after you. It also gives you the opportunity to leave more than the object information and include your perspective on why you were drawn to a piece.

Last, by cataloguing your collection, you’ll be surprised at what you might find. You may discover you have more pieces by a particular artist than you realized, which may lead you to contact them to get to know them more. Perhaps you’ll find some themes threaded through your collection of which you weren’t aware. For example, you might find you have a penchant for pendants, or that you tend toward a certain form or material, and even that you own a very rare piece you didn’t know was important.

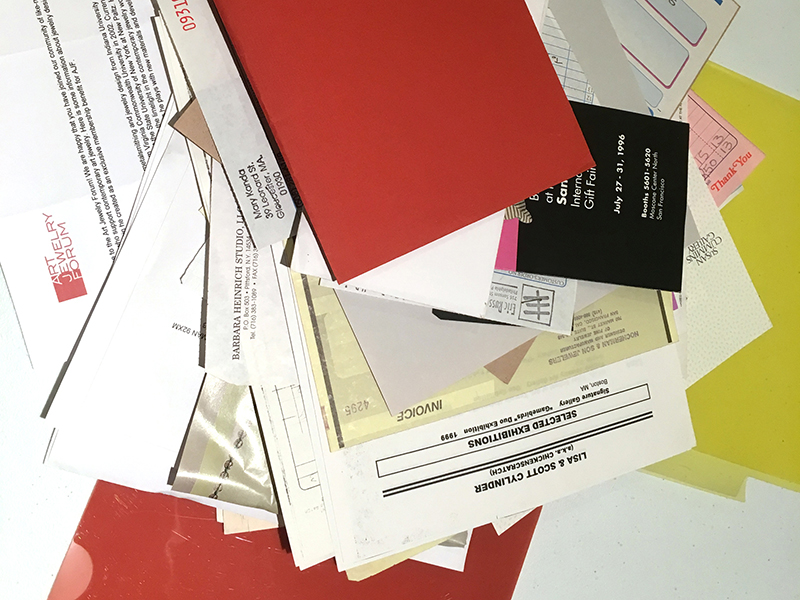

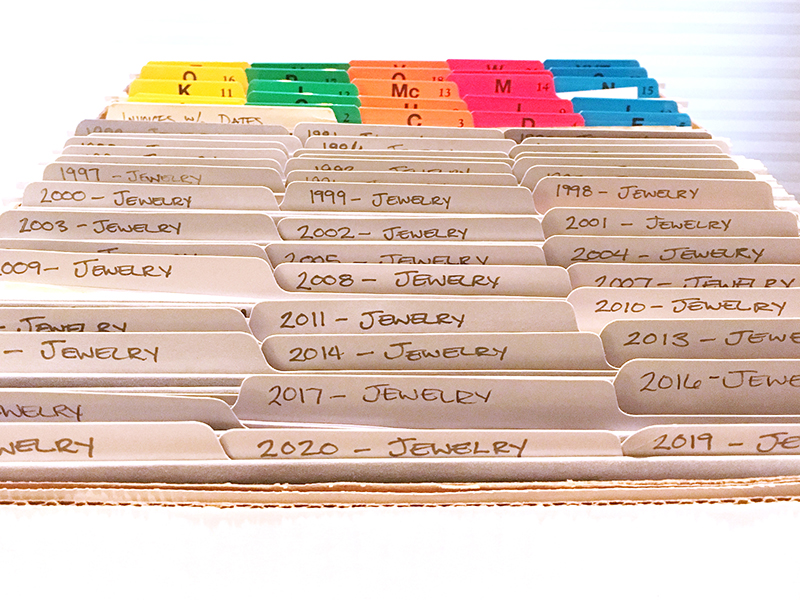

GETTING STARTED: FILING

The first step is to start with a simple paper filing system so that you can manage all the artist info, CVs, brochures, invoices, and other paper materials. Sort all the artist documentation by last name, and sort invoices by year; it’s an easy way to get started.

Here’s a link to a simple explanation of how to get started with paper filing.

The next step is to create a digital filing system for the images, digital files, and scanned receipts you have already, and to add to as your collection grows. It’s best to store this information in the cloud; if it’s kept only on your computer, you won’t be able to retrieve it if your computer melts down, gets stolen, or what have you. I suggest you replicate the paper system you’re using. So, if you have all the paper invoices filed by year, and artists by last name, do the same online:

- Scan all the files (or take snapshots).

- Name the files in a consistent fashion. For example, you might always list the artist’s last name, the title of the work, and the thing shown in the scan. Let’s say you own several pieces by Helen Britton—one called 13N002and the other 13B008—you could name the receipts “Britton_13N002_receipt” and “Britton_13B008_receipt.”

- Organize the digital files into subfolders, just as you’ve done with the paper files.

Compiling the Data

You should consider collecting a wide range of data points for your pieces. Remember, anything is better than nothing. Here’s a list of common data points to note.

Artist: first name, last name, full name, email, website, nationality, date of birth, date of death, gender

Object: object type, materials, year made, description

Purchase: gallery/dealer, gallery email, gallery website, purchase date

Value: object value, purchase price, currency, discount

Documents: invoice, biography, CV

References: catalogs, articles, interviews, books

Images: formal images and snapshots of your piece from multiple angles; include markings, such as material and artist signature

Of course, this isn’t an exhaustive list of possible data points, but it’s a good place to start. You can always add more as you discover more about your collection and how you want to use it.

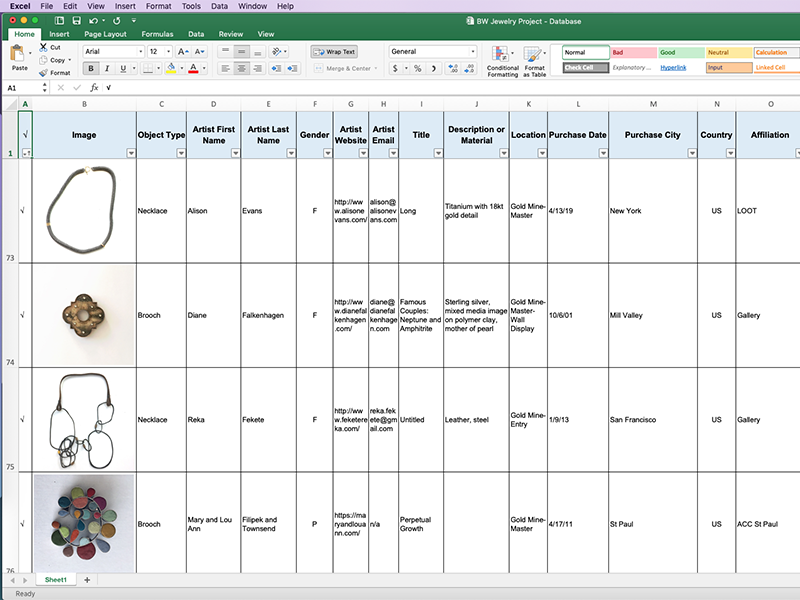

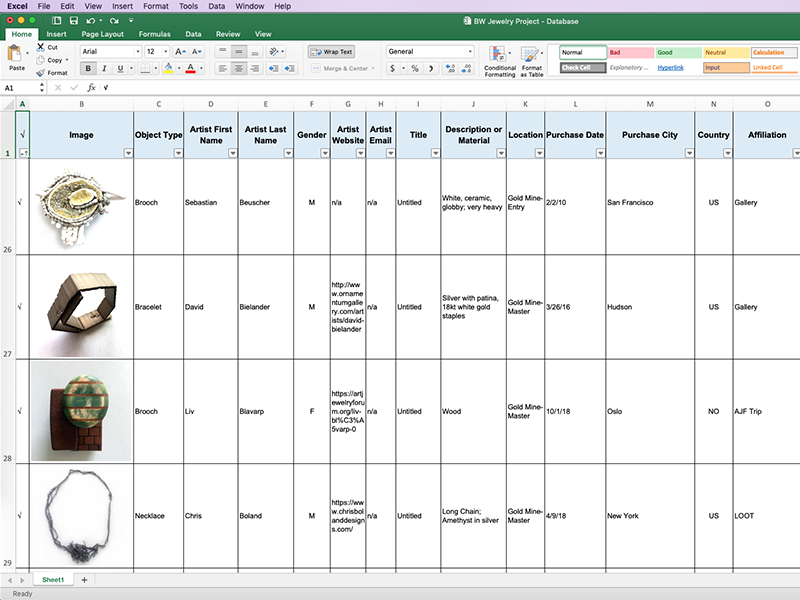

CREATING A SPREADSHEET

The basis of any advanced database is a simple spreadsheet, which is a fancy list with columns and rows for each piece of information. Spreadsheet programs are widely accessible and fairly easy to use. You most likely have Microsoft Excel or Mac’s Numbers on your computer, and you can always use the cloud-based Google Sheets. For collectors who are just starting out and who own 10 to 100 pieces, a spreadsheet is a good place to begin. Many who responded to the survey are already utilizing this versatile, easy-to-use tool.

Drawbacks to spreadsheets are that they can get unwieldy with too much data, which translates to a lot of scrolling. Furthermore, they’re designed for text, so adding images can slow them down and there’s the potential of a frozen screen. The images have to be tiny, and it takes a lot of effort to generate the results you want—for example, if you want to generate a listing of all the artists from the US working with bone.

As your collection grows, you can import the data you’ve collected from your spreadsheet into a database, so these initial efforts won’t be lost. If you want to skip making a spreadsheet and start directly inputting into a database because you plan to amass an extensive collection, go right ahead.

UPGRADING TO A DATABASE

When you’re ready to upgrade from a spreadsheet to a more robust system, you’ll find a wide range of databases designed for collectors. Databases differ from spreadsheets in their visually pleasing layout, searchability, and ability to generate reports. If you’re a geek like me, you’ll know that a spreadsheet is two-dimensional (left, right, up, and down) while a database is three-dimensional (left, right, up, down, forward, backward, and pirouettes.) Some databases that AJF community collectors reported using in the survey are: Filemaker, ArtVault, My Art Collection, Collector Systems, Collectify, and Adlib.

A common starting point is Filemaker, a powerful software tool for creating custom databases that costs $540 for an individual. AJF board member and established collector Susan Cummins has created a template she’s willing to share with other AJF members. Note, however, that if you aren’t already familiar with Filemaker, there is a steep learning curve. My goal is to encourage jewelry collectors to get started, so I’ll focus on two systems with intuitive user interfaces and visually attractive layouts that are much easier to use: My Art Collection and Collector Systems.

One of them is cloud-based and the other is desktop-based. The key difference in these databases is where and when you can access them from. If you use a cloud-based database, you can log into it from any computer, anywhere in the world. You can only access the desktop-based database from your own computer, although if it’s a laptop you can of course use it anyplace. Only you can know if having your collection database accessible while on a trip or at an international fair is something you’ll want.

“Ford/Forlano has 31 years of jewelry making and we keep an ongoing archive of our work. When we see a collector at a show wearing an older piece made before we started our archiving system, we ask if we might borrow it back to have it photographed and included in the archives. We are happy to share this information with collectors for their own archive. This reaffirms our connections to them as collectors and our shared goal of archiving the work.”

—David Forlano of Ford/Forlano

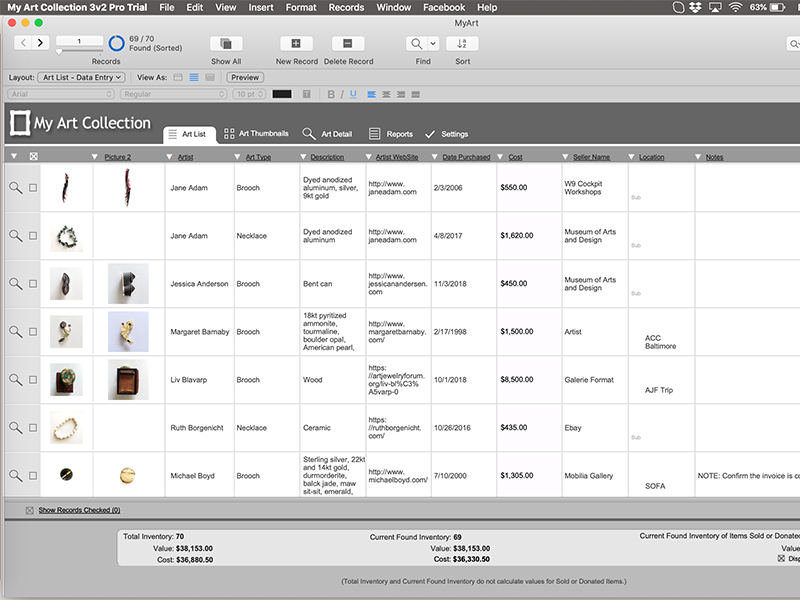

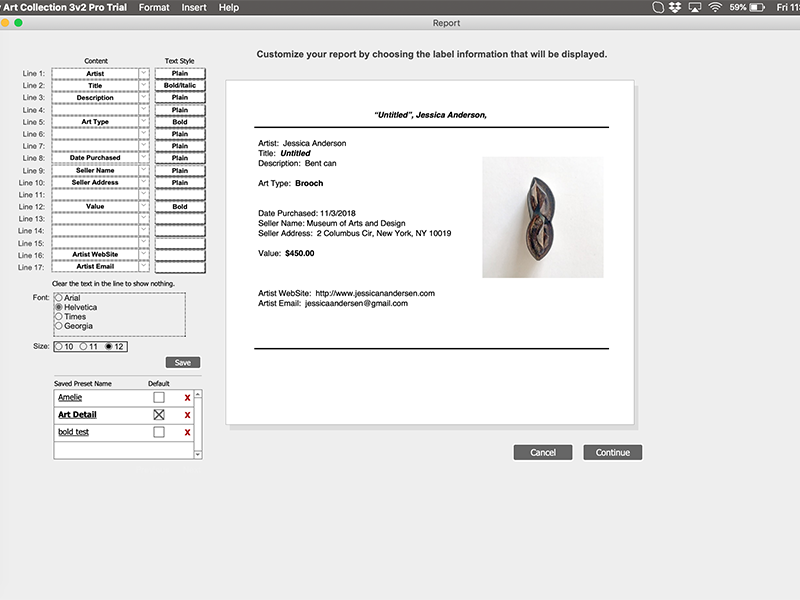

My Art Collection: A Desktop-Based Database

My Art Collection started in 2004 and has evolved through different types of collection systems (wine, books, etc.) to focus on managing private art collections. The system costs between $299 and $499 and is built using Filemaker software. The difference between My Art Collection and Filemaker is that My Art Collection is already designed for the art collector, with the data points preset and ready to go. Once you’ve bought it, you download the database software and it lives on your desktop.

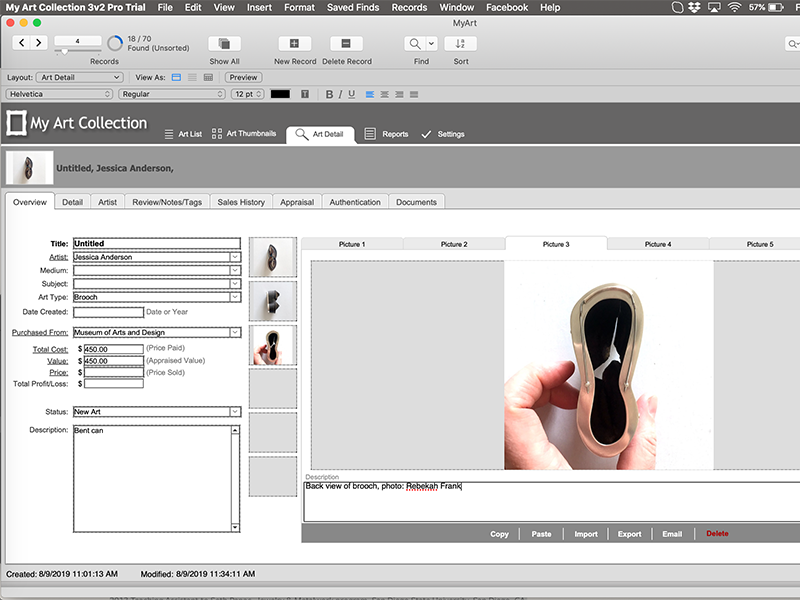

The database is attractive and very easy to navigate “out of the box.” The steps to upload your already created spreadsheet or to add an individual item are simple. You can sort the objects in your collection by any of your data points: object type, first name, gallery, etc., which is helpful in seeing, say, all the necklaces you own made by Iris Eichenberg and purchased from Ornamentum. This database makes it simple to create PDF reports based on criteria you select, so sharing it is easy. You might share such reports with an artist or a curator when loaning work for an exhibition. You may also want to share information with an appraiser or auction house, or with another collector, just to compare notes.

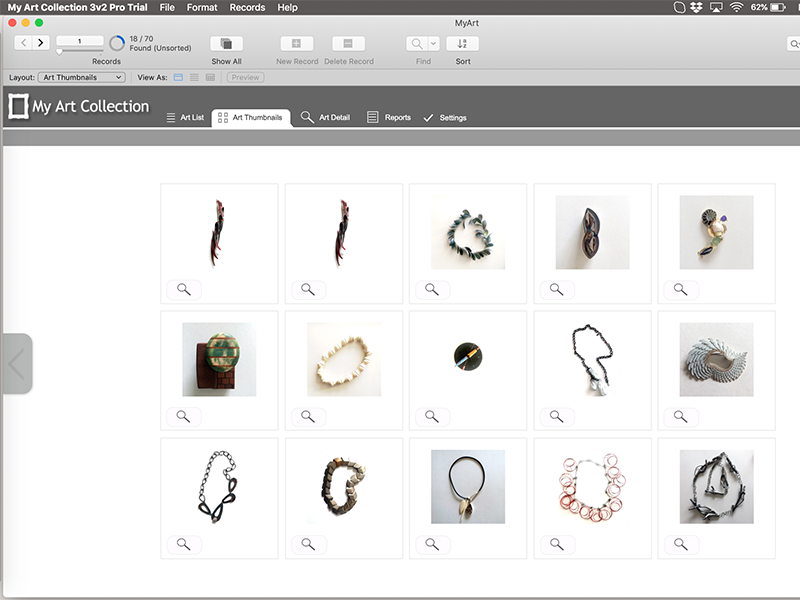

My Art Collection allows you to see the collection as line items, thumbnails, or details, each option giving you a different visual experience. In fact, the visual aspect of databases in general is what makes them more exciting to work with than a spreadsheet. It also allows for the storage and visibility of multiple images of each piece, along with the necessary photo credits. You can include formal images, perhaps provided by the artist or gallery, snapshots of the piece as you would wear it, or even photos of you and the artist to help personalize and memorialize your connection to the piece.

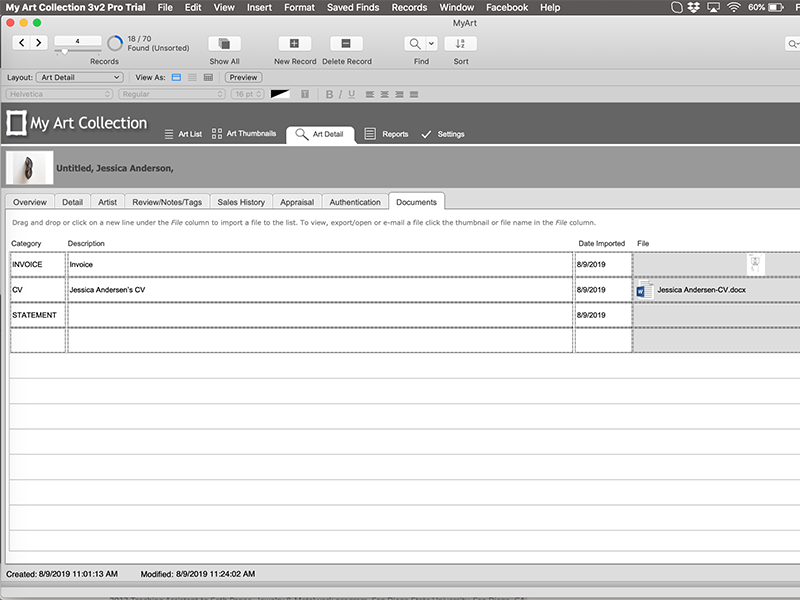

Additional documentation, such as invoices, biographies, CVs, and articles associated with each piece are also linked to the record. AJF is aware of the importance of this kind of documentation, and every article, review, and interview on its website is downloadable as a PDF so you can easily add AJF material to your database. Other kinds of publications, such as bibliographies and URLs, can be made in the Notes section, a convenient catch-all for information you may want to record but for which the system doesn’t provide specific fields.

The downside of using this particular database is that it lacks ease-of-use for mobile devices. While a version that’s accessible from iPad and iPhones exists, it requires several steps to set up, including the use of a server and a secondary app, and then the data doesn’t sync across platforms, which is unwieldy.

Like any database set up for the generic art collector, there are preset fields that aren’t as useful to the art jewelry collector, like frame data or authenticity documents, and it isn’t possible to hide unutilized fields. My Art Collection doesn’t provide the option to create custom fields, a limitation of this particular database. A useful field missing for both the art and art jewelry collector is the ability to record “collector’s premiums” or discounts given. Another missing option is the ability to record bibliographical data about the piece, but you can always add data in other designated notes fields to make sure that information is collected and associated with the artist or the object record.

My Art Collection is very easy to set up and a good alternative to a spreadsheet. It’s a sturdy option “out of the box,” offering the basics needed to view and search your collection with ease, as well as generate specific reports. In the event you run into difficulties, the customer service is good and the ability to see your collection in one place is satisfying.

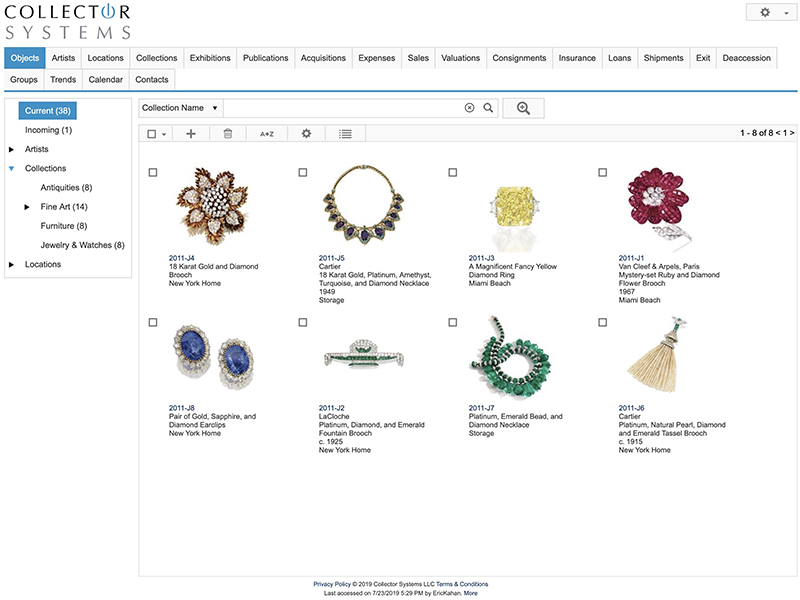

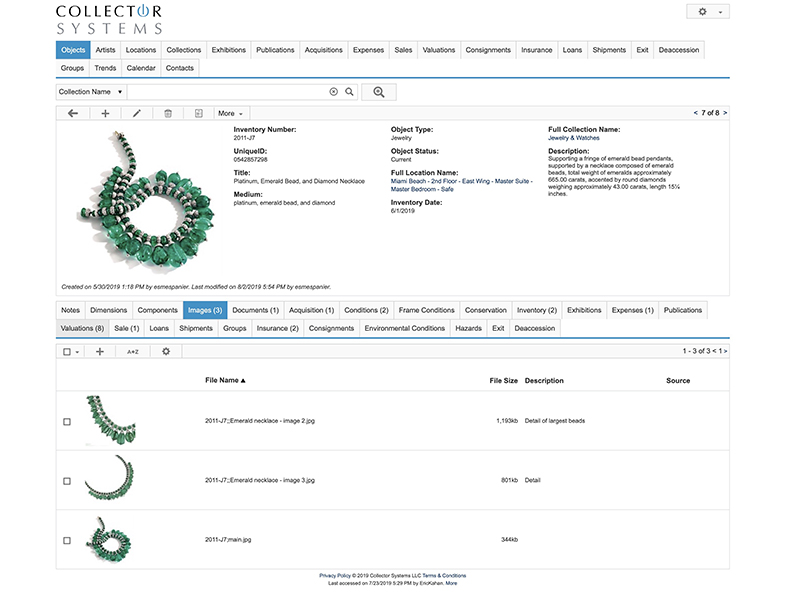

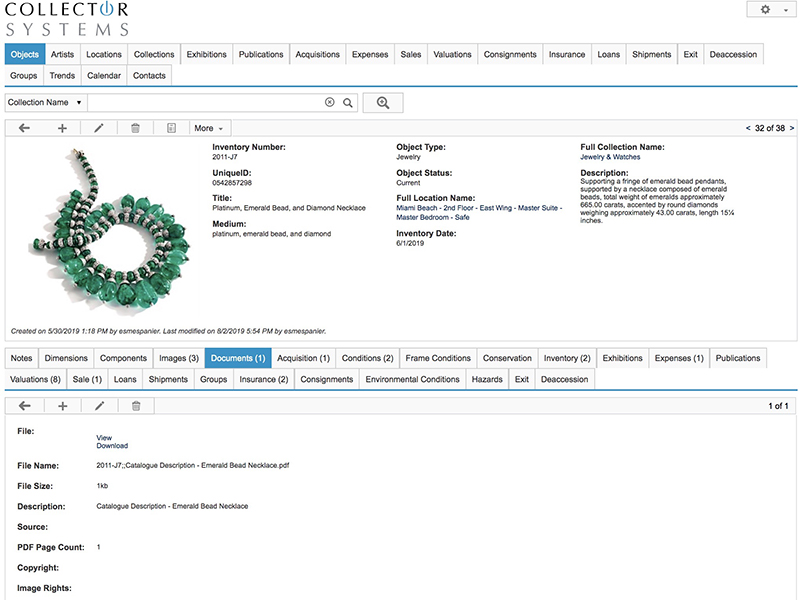

Collector Systems: A Cloud-Based Database

Collector Systems is a cloud-based system accessed through a secure login through any browser on any device. Basically, you access your collection information the same way you’d access your banking information online; it even uses the same security software as a bank does. A subscription to this system costs $85 per month, and the accessibility and ease-of-use on mobile platforms is its key selling point.

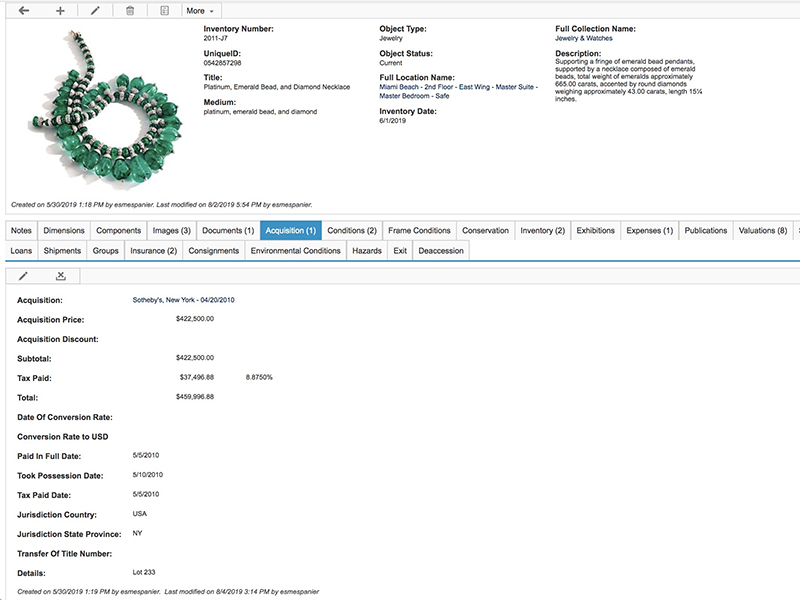

This system does not use Filemaker as its back-of-house software, which gives it a different look and feel, with less utilitarian gray backgrounds and softer edges. It provides a more aesthetically pleasing user experience, while still providing all the same things that a Filemaker-designed system does. It includes the storage of multiple images of a piece along with all photo credits, a broad range of preset data fields, and the ability to see the collection in a list, thumbnail, or detail view, along with the ability to generate curated reports.

Collector Systems has the additional ability to add custom fields, which is great if you want to track certain data not preset into the system. For example, you might want to add a custom field to track the pieces you purchased while on an AJF trip. Another unique feature is the ability to curate “galleries” of subgroups of pieces from your collection, say, all the necklaces you have made from a particular material or by a certain artist. Then you can share this unique gallery with others through a dedicated URL. You could use this feature when working with an artist to verify the full data for the pieces in your collection, or by generating a gallery of pieces that an independent curator is wishing to borrow.

An important downside for this system, besides its monthly subscription fee, is the complex import process which requires that the data be very clean (i.e., without errors). The company provides two templates to help with the multi-step import process, allowing you to match their field names to your spreadsheet. Collector Systems’s customer service is available to navigate the process and they are incredibly patient and kind. Post-import, the system is intuitive and easy to use.

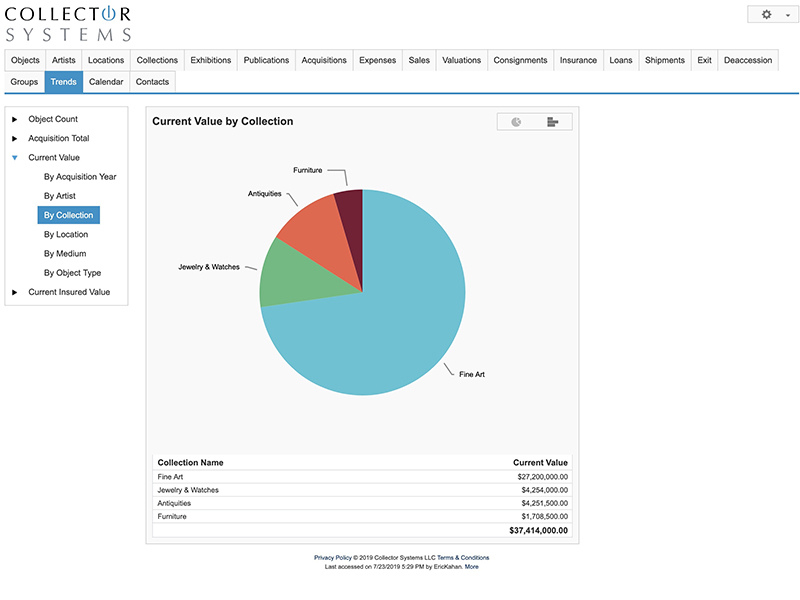

Finally, while I would describe the user experience of My Art Collection as utilitarian, Collector Systems’s experience is elegant. You can generate more varied reports, including the gallery feature, and you can view the database through built-in charts, graphs, etc. that give you a more complete understanding of your collection.

CONCLUSION

Are you still with me? This is a lot of information in a single article, and it’s not even the tip of the iceberg in the exciting world of collection databases. My goal is to introduce some options to get you thinking about what you could do. Remember, as your love of art jewelry grows, so does your responsibility to the artists you collect, to the field, and to yourself to recognize the value of the work.

Cataloguing your collection may seem like an insurmountable obstacle. As AJF member Susan Kempin notes, this is particularly true after you’ve been collecting several years. She points out that the best way to begin is just to begin. For the time being, don’t worry about cataloguing the pieces you already own. Set up a spreadsheet and enter the information you have for the next piece you purchase and continue adding each successive piece. Getting started cataloguing your new pieces may eventually motivate you to begin to work backward to catalogue the earlier pieces you’ve collected.

The process of cataloguing will help you discover much about your pieces and the artists who made them. You’ll also discover more about yourself, what pieces you’re drawn to, and perhaps even that you have an unrecognized predilection for … I don’t know, you’ll find out once you dive in. When you really look at it, archiving is a form of storytelling—you just have to find the story within.