Also in this series:

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Demetri Broxton’s Beaded Boxing Gloves

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Angela Hennessy

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Monica Canilao

This is the third article in a series focused on artists whose work is adjacent to jewelry. For my purposes, jewelry-adjacent artists use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field.

Hollis Chitto (Choctaw/Isleta and Laguna Pueblos) began his artistic exploration with quillwork. He shifted to beadwork early in his creative development, attracted to the color and versatility of beads. Based in Santa Fe, NM, he was surrounded by talented artists and artisans growing up. His grandmother was a beader and his father worked with clay. His family sponsored Jamie Okuma[1] (Luiseno/Shoshone-Bannock/Wailaki/Okinawanone), providing a fellowship to support her early career. Okuma’s work includes beaded stilettos, spiked backpacks, and bomber jackets, and now includes fashion design. It was an early influence for Chitto to understand the potential of beading.

When he was five, he began attending the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA) market with his father. He started selling beadwork at age 10. He had learned techniques through books and practiced until he got it right. The SWAIA market was an ideal place to connect with other beaders. He met Ken Williams, Jr.,[2] (Northern Arapaho/Cattaraugus Seneca) there. Williams became a major influence on his work. The accumulation of knowledge, relationships, and connections aided Chitto’s development of his personal style. His concepts and designs veer outside of traditional motifs of beaded jewelry. (Though he does that, too!) For example, he brings HIV/AIDS and queerness directly into his work.

European traders and colonizers introduced glass beads to the already established cultural traditions of the many Native people living in North America as early as the 1600s. They were incorporated into some Native tribes’ unique creative lexicons. Beads continue to be used as both a traditional and contemporary material today. Like craftspeople the world over, Choctaw and other Native tribes merge centuries of knowledge and techniques with different Indigenous, European, and Asian materials to create distinct beaded objects.

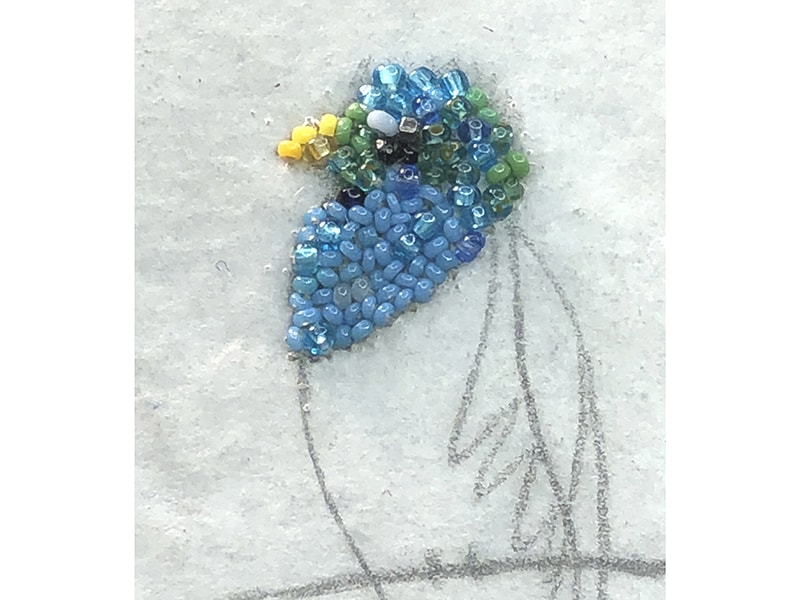

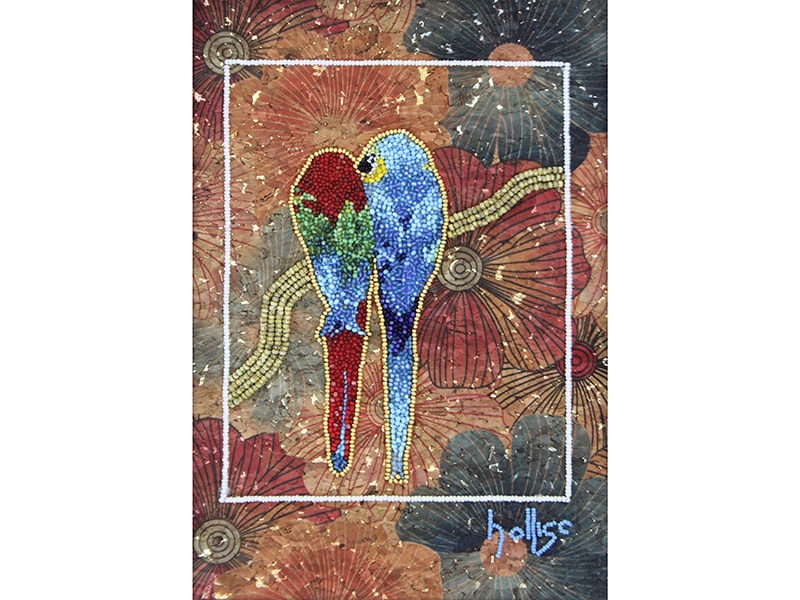

The style of beading Chitto uses in his work follows the outline of a drawing. This method is called contour beading. Filling the space from the outside in creates a halo or ripple effect as the outline of the image radiates into the background. Chitto chooses vibrant, saturated colors. He combines traditional Pueblo pottery motifs and Art Nouveau sensibilities in his designs. The artist thinks of beading more like coloring and less like sewing, but needles and thread are involved in the process. He uses both single stitch and two-needle applique to make his work, occasionally incorporating other techniques like wire wrapping and pearl knots for details.

Besides a few pieces inspired by bird photographs, Chitto’s work features bold, geometric flowers. Floral patterns in Native work trace back to French-Canadian traders and nuns. They shared floral motifs, and Native beaders expanded on the designs. These floral designs evolved over generations. Individual style and choices are reflected in subtle decisions about the color, size, material, and shape of the beads preferred by each tribe and then by each beader.

“I always tell people I do abstract flowers because I can’t draw.”[3]

Chitto takes many notes during his creative process. Descriptive written reminders keep ideas, dreams, colors, materials, and other points of inspiration from being lost. Each piece starts with a list of these ideas to prompt his design process. Chitto says he can’t draw. So he lays out the map of the illustration for each of his pieces, just like a sketch underlies a painting. His discomfort with his drawing skills disappears during the beading process. The beads create the graphic form, hiding the drawn lines in the process.

Chitto takes full advantage of the colorful vibrancy of beads. The variety of finishes and sizes provides him plenty of creative potential. Most of the beads Chitto uses are Czech glass seed beads. These are known for their variability of form. He finds Japanese beads too square for curved designs. The smallest beads are 24/0 and the largest is 16/0. (For reference, a 15/0 seed bead is approximately 1.3 mm or 0.05 inch, so these are tiny. The sizing describes how many beads fit lined up along a linear inch when positioned hole up. It is pronounced “fifteen ott,” similar to jewelry saw blades.)

The award-winning piece Resplendent Quetzal is the first time Chitto featured realistic imagery of a bird in his work. He drew inspiration from an exhibit at the Field Museum, in Chicago. It featured a resplendent quetzal. This bird, native to Central America, has colorful, even flamboyant, plumage. Working from a photograph he took of the exhibit, Chitto created several drawings that guided the beading.

Resplendent Quetzal is a traditional cornmeal bag. It includes sterling silver beads along with vintage microbeads and wampum beads, which are beads made from polished shells. Pueblo people wear a cornmeal bag for daily prayers. Women wear the small bag suspended from the neck, while men wear a different style with a flap. It is similar to a small bandolier bag, and worn at the hip.[4] This small bag holds cornmeal used during ritual prayer. It joins the long tradition of beautifully crafted devotional and ceremonial objects made by skilled artisans. These objects range from prayer shawls and rugs to various prayer beads like the Catholic rosary and the Buddhist mala.

It’s hard to imagine now, but clothing, specifically men’s clothing, didn’t have pockets until the 16th century.[5] Women still struggle to find functional pockets in clothing. The evidence? The phrase, “Thanks, it has pockets”—the perfect answer to a compliment on an outfit. What were the solutions before pockets held the minutiae of everyday life? Shoulder bags, small bags suspended from the neck on a cord, pouches worn around the waist, and the more elaborate chatelaines. Bags are utilitarian. They keep useful items, ritual objects, and small necessaries like keys close at hand. Purses are slightly different than bags. They are elevated by their beauty and elegance, and combine utility and decoration in a single fashionable accessory.

Chitto’s work focuses on traditional Native bags, like the cornmeal bag and the bandolier bag. However, the work of Sandra Okuma[6] (Shoshone-Bannock/Luiseno) inspired Chitto to integrate Western-style, mechanical-looking purse frames into his pieces. He started this in 2012. The tension between usefulness and artistry excites Chitto, who makes sure that every bag he makes is usable. He lines them with silk and makes sure important everyday items like cell phones fit securely in the purse. The antique frames also make the purses more wearable by providing a mechanical clasp for closure.

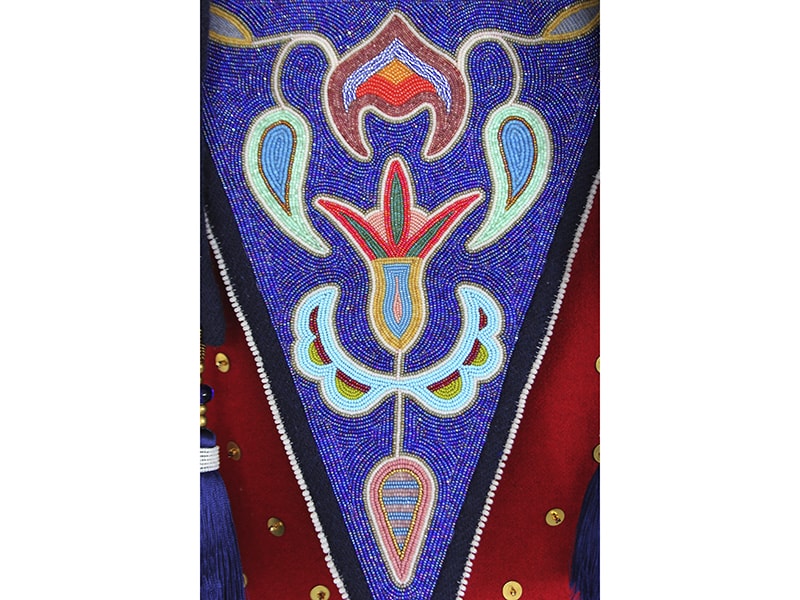

Traditionally, fully beaded bags are worn to large, special community events like pow-wows and Stomp Dances, where the goal is to stun and impress people with your fashion and artistry. They are equivalent to the evening bags carried to galas in Western high society. Chitto’s bandolier bag Chata Anumpa in My Accent was worn by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in a cover shoot for InStyle magazine in 2021. It is an example of the powerful effect of a beaded bag worn by a Native woman in full regalia.

For Chata Anumpa in My Accent, Chitto began with an idea, an artist statement, in mind. Overall, the bandolier bag is traditional in its format. It has a single wide, flat strap meant to be worn over one shoulder and across the chest. Cords at the corners attach the strap to the flat pouch. Decorative tassels hang from the bottom of the bag and straps. A simple flap closure finishes the design. However, Chitto actively considered which traditional elements to keep and/or alter to create something uniquely his own.

For example, Choctaw beaders don’t traditionally fully bead the flap closure. Instead, they apply wool cutouts and bead around them. Chitto wanted to showcase more beading, so he beaded the full flap with abstract geometric florals on an iridescent indigo field. Some of these beaded elements are repeated on the shoulder strap. The designs he chose are uniquely his, not traditional Choctaw. For example, Choctaw don’t traditionally bead flowers or use minimal colors. As Chitto said during an interview, “When you wear it, you’re gonna know it’s not traditional, but it’s doing its best.”[7]

The title and ideas behind this piece relate to Chitto’s personal goal of learning Chata Anumpa, the Choctaw language.[8] His father grew up on the Choctaw reservation in Mississippi, where 75% of the children learn to speak Choctaw fluently as their first language.[9] However, Chitto didn’t grow up there. English is his first language. While studying the book Choctaw Grammar, he learned Choctaw men say the “t” sound forward in the mouth while Choctaw women say the “t” sound farther back in the mouth. This binary language rule doesn’t hold space for Chitto, who is two-spirit and uses pronouns he/they. Where should the “t” sound sit in his mouth? This quandary made him think of the 2015 documentary Do I Sound Gay?[10] The film explores how some gay men merge the tonal habits of both male and female speaking characteristics.

Related to binary traditions, as Maynard White Owl Lavadour (Cayuse/Nez Perce) states in his essay for the Heard Museum about beading, “among most beadworking tribes, it was traditionally the women who did most of the beadwork.”[11] As a young boy, Chitto idealized the strong beading women in his life. Generally, Choctaw men painted, while women beaded. So this is another area where Chitto straddles binary expectations of gender roles. Chitto’s two-spirit identity allows him to make work that merges painting and beading, blurring the divide between traditionally held female and male roles. In doing so, he creates work that is neither and both.

Through his work, Chitto wants to start conversations about how HIV/AIDS continues to affect reservation communities. Although HIV/AIDS diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, open conversation remains key to healthy outcomes. From his artist statement about the BloodWork series, which includes a bracelet and a bag:

“HIV infection rates in native people have consistently ranked third in the nation[…]. Underrepresentation and misleading figures veil the fact that new HIV infections in the native population are steadily rising and have been for the past 15 years. The lack of frank and open communication based around safe sex plays its role in this increase. The taboos of speaking openly about unsafe sex and high-risk behaviors such as intravenous drug use have only served to add to new infection rates due to ignorance.”[12]

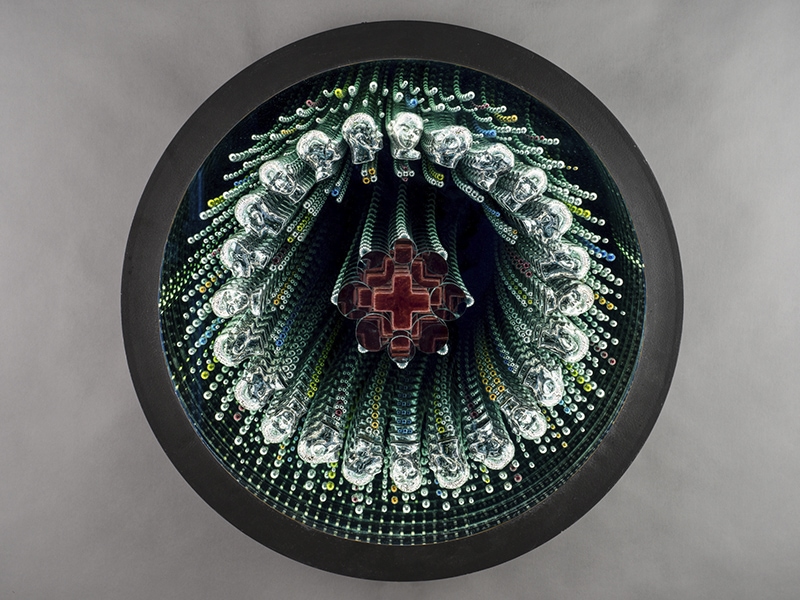

The first piece in the BloodWork series was a quilled bracelet. It referenced the heartbeat and the pulse, connecting the placement of the bracelet to the life force flowing through the wrist. Bloodwork Number 2 further reflects on the importance of blood to life. It stems from Chitto’s concern for the homosexual men in his community. HIV/AIDS still holds a strong taboo within Native communities. This, Chitto points out, is counterproductive in protecting themselves and the community as a whole from a highly transmissible virus.[13]

In Bloodwork 2, red beads representing blood cascade over the floral design, disrupting the balanced harmony of the piece. However, Chitto chose different tones of red beads. They don’t obscure the pattern. They also make the blood seem translucent. This allows the underlying pattern to show through. Through this painterly visual effect, Chitto conveys that the disruption of a positive HIV diagnosis isn’t an erasure but becomes part of the whole person.

The embroidery on the back of the bag includes morning stars, represented as plus signs, on a dark blue field. These plus signs do double duty. They are both morning stars and the symbol of a positive diagnosis of HIV. Morning stars are a common design trope in many Native tribes. For Chitto, the universality of the morning star across Native cultures helps convey the importance of HIV/AIDS awareness. Bloodwork Number 2 holds a special place in Chitto’s evolution as an artist, allowing the messaging and concepts to drive his aesthetic choices.

“All art is a form of release in some way, both for the artist and for the appreciator.”[14]

Creating work about HIV/AIDS has strong connections in the art world. Chitto’s work joins the work of many artists who created work reflecting on the HIV/AIDS epidemic. He takes inspiration directly from the simple power of Felix González-Torres’s Candy Works.[15] Other examples include glass artist Tim Tate, who also uses the powerful symbol of the plus sign as an HIV/AIDS indicator in his cast and mirrored glass wall pieces.[16] There is also jeweler Keith Lewis, whose iconic necklace 35 Dead Souls represents the loved ones he lost during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis.[17]

Exploring ideas about social issues is new for Chitto. It’s exciting to see the talented artist’s bold beadwork speak about the relevant societal problems and personal dilemmas he experiences. His bags are more than fashionable accessories, though they have been featured for their style and artistry in Vogue, InStyle, and HuffPost. The exploration of his identity, the difficulty of navigating gendered language, and the unique challenges of discussing issues like HIV/AIDS in Native communities brings his work into other art world conversations. In these arenas, the concept supersedes the need to stylishly carry a cell phone—as handy as that may be—and brings awareness to important issues through the beauty of the object.

Bonus: You’re invited to listen to a playlist created by Hollis Chitto on YouTube. These are the songs he beads by.[18]

[1] To see Jamie Okuma’s work: https://www.jokuma.com/gallery.

[2] To see Ken Williams, Jr.,’s work: https://www.instagram.com/kennwilliamsjr.

[3] Kathleen Roberts, “I Do Abstract Flowers Because I Can’t Draw,” Albuquerque Journal, Aug. 16, 2020, https://www.abqjournal.com/1486505/i-do-abstract-flowers-because-i-cant-draw.html.

[4] From a conversation with the artist, October 18, 2021.

[5] Sigrid Ivo, Bags: A Selection from the Museum of Bags and Purses (The Pepin Press: Amsterdam, 2011).

[6] https://www.southwestart.com/articles-interviews/featured-artists/sandra_okuma.

[7] Interview with the artist, May 24, 2021.

[8] To hear Choctaw pronunciation and review introductory grammar lessons, visit the official Choctaw School website: https://choctawschool.com/language-lessons/choctaw-alphabet.aspx.

[9] From a conversation with the artist, October 18, 2021.

[10] David Thorpe, Do I Sound Gay?, 2015, IFCFilms, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R21Fd8-Apf0.

[11] Maynard White Owl Lavadour, “Dazzling Beadwork,” in Be Dazzled Masterworks and Jewelry from the Heard Museum, ed. Gail Bird (Phoenix, AZ: Heard Museum, 2001). https://www.mutualart.com/Article/Dazzling-beadwork/0498A9776E9E8754.

[12] From Hollis Chitto’s artist statement: https://www.hechoamano.org/art/bloodwork-number-2-by-hollis-chitto.

[13] Interview with the artist, May 24, 2021.

[14] Staci Golar, “Creating during a Planetary Pandemic,” First American Art Magazine, Apr. 3, 2020, https://firstamericanartmagazine.com/pandemic-hollis-chitto/.

[15] To see images of Felix González-Torres’s series Candy Works: https://www.felixgonzalez-torresfoundation.org/works/c/candy-works.

[16] To see images of Tim Tate’s work: https://www.timtateglass.com/current-works.

[17] To see images of Keith Lewis’s work: https://www.facebook.com/keith.lewis.3760/media_set?set=a.1257339350131.2034388.1129030220&type=3.

[18] To listen to this playlist: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60MHmrtEuRY&list=PLFM28zkQ_n_uBglZcmYjRcyCf9f528xmw&index=66.