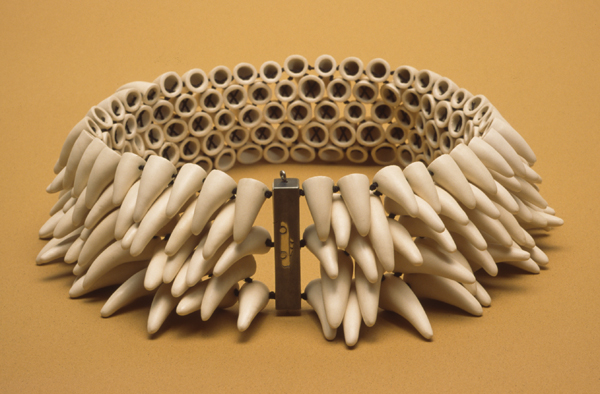

Hoogeboom’s jewelry often operates cross-culturally: Through its title and the appearance of the repeated ceramic elements, Show Your Teeth makes reference to the teeth necklaces that are found throughout the Pacific. A quick scan through Roger Neich and Fuli Pereira’s book Pacific Jewellery and Adornment (David Bateman, 2004) reveals necklaces using teeth from whales, sharks, porpoise, pigs, dogs, and flying fox. While there are no ceramic teeth, it wasn’t uncommon for Pacific peoples to shape teeth out of other materials, such as bone or stone.

Like the most impressive examples of Pacific adornment using teeth, Hoogeboom’s work achieves its effects through quantity and repetition, a wealth of teeth that project outward in a display of potential violence that circles the neck, one of the most fragile parts of the human body. The image of the flashy car on the silver catch links the luxury items that, in the West, indicate status and affluence to the meaning of teeth in the Pacific. Teeth were scarce because there weren’t many animals you could get them from, and possessing a large number of them was a mark of plentiful resources and great wealth. Hoogeboom’s necklace reminds us that using hard-to-obtain materials to establish and display importance is found throughout all human societies.

This cross-cultural awareness is part of why I like Hoogeboom’s necklace. It is an example of international contemporary jewelry that constructs a wider history and geography for the practice, to the point where someone like me, from a small set of islands in the Pacific, can see something of the history and culture that shapes my reality reflected in an object from somewhere else entirely. (As New Zealand jeweler Warwick Freeman once said, and I’m paraphrasing here, he doesn’t mind if his jewelry looks like it came from the bottom of a lagoon, he’ll still show it in Amsterdam. Well, here is an object from Amsterdam that would look quite at home in a lagoon, or on the streets of Auckland, the biggest Pacific city.) The world is enlarged through such gestures, although I also acknowledge that such gestures across cultural boundaries are not always straightforward, nor read or understood in the same ways.

Fuli Pereira, Curator Pacific at the Auckland Museum, commented to me that while Hoogeboom’s necklace looked similar to Pacific adornment, it felt quite different. In areas of the Pacific, teeth—like bird bills and tusks—are displays of culturally acceptable systems of socio-economic aggression, like owning a mansion or a showy car in the West to show your status. In contrast, Hoogeboom’s necklace is a countercultural display of aggression, an attack on the conventional jewelry that is publicly accepted in the West. It uses teeth, and their aesthetic similarities to Pacific adornment, to challenge social standards; teeth necklaces in the Pacific reinforce social standards.

The other reason I like Show Your Teeth has to do with how it looks and feels. There is something about the tactile quality of the ceramic teeth that rewards touch. They move dynamically as a result of the way Hoogeboom has strung them together, and much like Hawaiian dog’s teeth leg ornaments, they clink and softly rattle, which only becomes apparent when you touch and wear the necklace. The open circles of the teeth along the interior of the necklace feel smooth and flexible against the skin of your neck. And together with these characteristics, I like how the work, when it isn’t being worn, can never sit precisely right. It flexes and dips in a way that declares its need for the neck, its requirement to be worn, and also indicates how responsive it will be when you put it on. For all its visual sense that this is a necklace of ferocious bite, Show Your Teeth reveals itself to be a piece of jewelry that handles its wearer with care and tenderness.