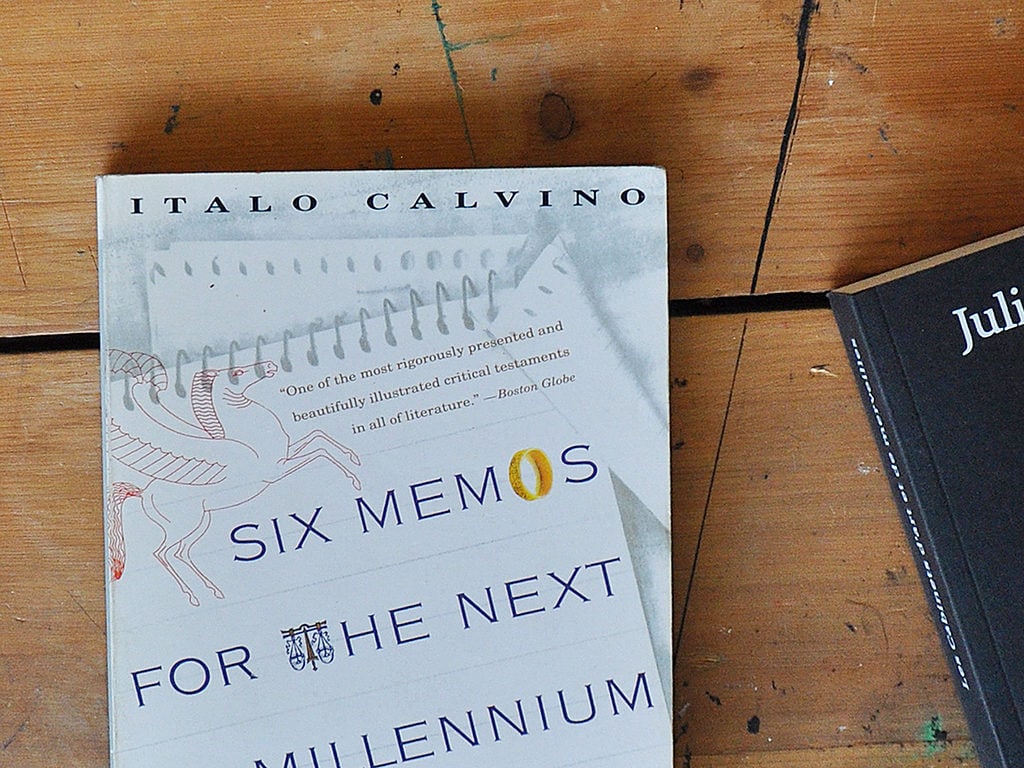

This summer, I am going to re-read…

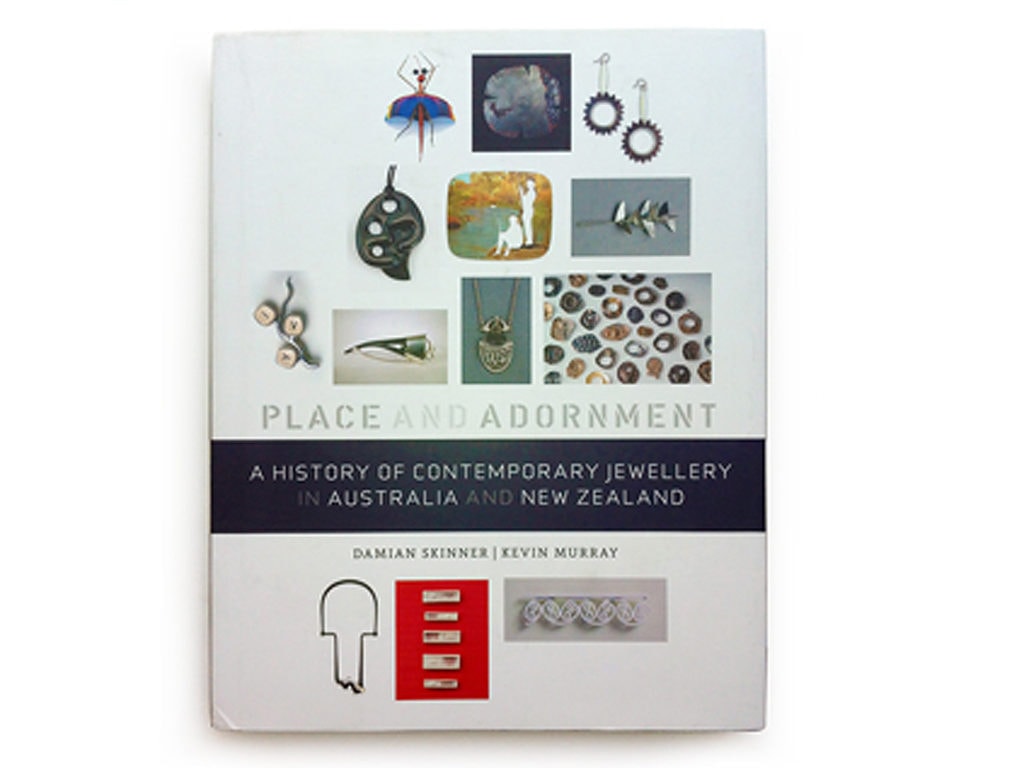

Reading is seasonal. Come June, we head down the nearest Amazon shop—well, you know what I mean—to buy what your downstairs neighbor calls a “summer read” while wrapping a bashful smile around the latest Le Carré, which happens to be poking out of his beach tote. Meanwhile AJF, being of the WTF persuasion, believes that…