After Limoges, New York and Taipei, the 140 contemporary ceramic ornaments in Un peu de terre sur la peau arrived at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris in March. (After it closes in August, the exhibition travels to Toronto, Canada.)

It has been a long time since the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris has hosted an exhibition exclusively dedicated to contemporary jewelry. The Triennale of contemporary jewelry occurred in 1992 and in 1999, when eleven contemporary jewelers were featured in an exhibition alongside the jeweler Line Vautrin, who was popular in the 1950s. In 2003, costume jewelry and high fashion jewelry won the attention of the museum, while in 2008 there was a small survey of the Swiss designer Dieter Roth. This was more a design statement than a jewelry event. The great 2009 exhibition of the jeweler Jean Després, active in the 1930s, housed in the imposing nave of the museum, concentrated on the production of this jeweler before World War II, with few big names of that time. In 2011, the musuem rejected Also Known As Jewellery, an exhibition of seventeen contemporary French jewelers. (You can read a review of the catalog for this exhibition on the AJF website.) Wishing to present these experimental jewels in Paris, the organizers of that exhibition had to ‘settle for’ space of the Ateliers de Paris. A farce: talented jewelers institutionally unrecognized in their own land!

In addition to antique jewelry, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris has opened a space called ‘The Gallery of Jewels.’ It is the permanent host to a nice collection of contemporary ornaments from the 1960s to the present, even if more recent pieces would be welcome. In all, there are about 500 items of purchased, loaned or donated jewelry, presented in this space, renovated in 2004. Even if it is a little dark, with the labels not easily readable and difficult to see in the dimness, the space exists and can be visited. But a museum does not only live through its permanent collections; temporary exhibitions can provide an opportunity to address, prospectively, other issues or specific themes. How can we begin to understand such a lack of love for experimental jewelry in general in France? If the first duty of a museum is transmission, how is it possible to skip a whole section of contemporary creation?

Of course, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris is not the only institution responsible for this invisibility or denial; the whole country seems to participate in this rejection. Compared to the more than dozen traditional schools in France and all the traditional shops that sell traditional jewelry every day, there are very few galleries, very few collectors, very few newspaper articles and very few schools (Afedap in Paris, Atelier Bijou de l’école des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg and école Nationale Supérieure d’Art de Limoges) dedicated to contemporary, experimental jewelry. However, ‘some’ is not none – galleries like Helene Poree, Naila Montbrison and Elsa Vanier, join collectors like Flo Fleiss and Barbara Berger and a few auctions to act as proof of the existence of a very small market. But the absence or rejection of contemporary jewelry is not noticeable only in France. Recently, the Jewellery Unleashed! symposium in the Netherlands discussed the lack of visibility for contemporary jewelry on a European scale, among other things. We are facing a general problem: a difficulty to recognize a particular area, which is no longer the same as jewelry in general.

It seems that France, with its rich history of jewelry, should be able to sustain all sectors of the jewelry community: fine jewelry (Cartier, Boucheron, Van Cleef & Arpels); jewelry (Van Dinh, Jean Vendome); fashion (House Gripoix, Robert Goossens and Roger Jean-Pierre for the oldest, Natalia Brilli, Ligia Dias or Laetitia Crahay for those of today); costume jewelry; jewelry by artists (from Picasso and Braque to Louise Bourgeois and Bernar Venet for the most current); and last but not least, contemporary jewelry. And yet this isn’t what happens. To return to the exhibition being reviewed here, as a case study of the power dynamics: Un peu de terre sur la peau is displayed in a small space on the fifth floor of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris while, in September, this museum hosts a retrospective of Van Cleef & Arpels on the ground floor in the big nave. In 2011, Victoire de Castellane, artistic director of Dior’s jewelry line, exhibited her jewelry in the famous Gagosian Gallery. A paradox: why does a place dedicated to contemporary art (the most experimental at the moment) not exhibit contemporary jewelry (the most experimental at the moment)? A last example: very recently, the Fondation Cartier, which has exhibited only contemporary art since its opening in 1984, presented Cartier Jeweller Arts, an exhibition with ‘pieces’ created from gemstones by Takeshi Kitano, David Lynch and Alessandro Mendini. Again, why not show the very innovative work made by contemporary jewelers, or ask them directly to take part in this project?

In this difficult and paradoxical context, the arrival of the exhibition Un peu de terre sur la peau is a small victory, its form and content being very stimulating. The Bernardaud Foundation, established by the Limoges porcelain industrialist Michel Bernardaud in 2002, is both the initiator of this project and the financial sponsor – perhaps the reason why the exhibition has been shown at this very museum. In recent years, this famous porcelain factory, founded in Limoges in 1863, has set a goal to explore new areas and to generate interdisciplinary dialogue through the Foundation, which works with artists, organizes exhibitions and celebrates the intelligence of the hand. This exhibition is one of its beautiful fruits!

The general problem that the exhibition develops is the importance of a technique to a field that has not traditionally been concerned with this material or the skills required to use it. Ceramics (a material and a process conventionally and mainly devoted to the arts of the table) when transposed to the world of jewelry and in its four possible types (earthenware, stoneware, porcelain and bone china) allows the manufacture of unusual and new objects. In a slightly purple ambience, modules have been placed (one for each artist) against the walls and in the center of the space. The directional spotlights ask the viewer to shift slightly in order to see and, placed very low, the labels are barely visible. However, the visitor flows easily from one showcase to the other, from one jeweler to another. A total of eighteen jewelers and 140 objects demonstrate masterfully what contemporary jewelry can be.

The objects that catch the eye immediately are the imposing necklaces of Dutch jeweler Willemijn de Greef: those long hemp ropes, with their orange terracotta modules, representing the texture of the rope, threaded one after the other, are particularly spectacular. Walking around with such strings on the neck creates a certain visual effect that you cannot see in photographs of the work. The jeweler says he was inspired by the kraplap, a piece of clothing from the Dutch traditional costume, very colorful and enveloping the shoulders. The long necklaces of the Finnish jeweler Tiina Rajakallio are similarly surprising, with dark and uncertain contours and human hair, clay, cotton and rubber amalgamated and painted. A notable strangeness emerges from these hairy objects.

In a register oriented to recovery or reuse, Swiss jeweler Luzia Vogt, in a series of rings Flüchtige Momente, has ‘chiné’ some old objects to extract small fragments with a floral or animal decoration. The German jeweler Gesine Hackenberg makes objects that reveal the manufacturing process: a necklace composed of pierced pellets, collected from a decorated stoneware plate. The Dutch jeweler Manon Van Kouswijk presents her necklace Grey Pearl on a saucer: a pearl necklace of white porcelain, in which the pendant is the handle of a recovered cup. The serial Coffeecup Brooches from Dutch jeweler Ted Noten are made of teacups sliced from top to bottom. More monumentally, the French jeweler Marie Pendaries has pierced a dinner service of 28 pieces of porcelain to wear them: the dish becomes a necklace; plates, bowls, bowls, mugs and cups are bracelets; and coffee cups are rings.

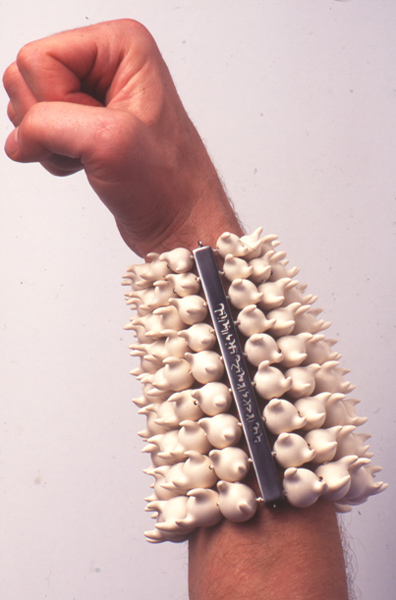

More strictly oriented to the exploitation of the technical aspects of ceramics, bulky jewelry from Dutch jeweler Peter Hoogeboom consists of a systematic assembly of small units of porcelain of the same dimensions, to create a new piece of clothing: a large bracelet like a sleeve, a scarf, a shirt collar. For her jewels, which are of fairly standard configurations (pearl necklaces or earrings called ‘girandole’) the Taiwanese jeweler Shu-lin Wu worked with the Japanese technique of mokume-gane, traditionally devoted to samurai armor. This ancient technique allows the jeweler to obtain many random new textures: duskiness, irregularities, inhomogenous colors.

For collars that seem classic, Finnish jeweler Terhi Tolvanen plays on the similarity of nature (juxtaposition of small branches) while the Netherlands’ Evert Nijland has protruded in relief, like buds, the kind of decorations that are traditionally painted on the surface of the porcelain. By meticulous work, less spectacular but pertinent, the rings of Swiss jeweler Andi Gut are created from dental ceramic. Their configurations, close to the proportions of a tooth, accentuate their medical references. This has something in common with the molding of female sexual organ on live models that French jeweler Carole Deltenre manufactures for her pins, all framed portraits of some intimate personal relationship.

Finally, two jewelers have specifically developed the notion of the unportable. The large elements in white porcelain by Swiss jeweler Christof Zellweger, hung by strips or straps of leather, are suspended from a coat rack with work clothes. Breakfast at Tiffany’s by fellow Swiss Natalie Luder is a disparate set of plates arranged in a large box, like beads of a necklace.

Dimension, recovery, technical operation, manipulation or provocation . . . this exhibition highlights some creative levers of contemporary jewelry. Applied to jewelry, the implementation of this specific material highlights its wealth of creative possibilities. This demonstration of beneficial innovations is economically vital for a company like Bernardaud and for contemporary jewelry, which is always ready to experiment but which has no real space to expose its strengths and creative resources.

The author would like to thank Nathalie Nyault for her help in translating this text into English.