Manfred Bischoff, Tribute to Manfred Bischoff

March 9 – April 8, 2017

Galerie Handwerk, Munich, Germany

The first impression of the Tribute to Manfred Bischoff exhibition is dominated by the large photographs on the walls of the Handwerkskammer exhibition space in Munich. They show the interior of the ancient Capuchin convent in San Casciano dei Bagni, Italy, where the German artist lived from 2000 until his death. The images are an inviting welcome because they give the illusion of entering someone’s personal space, yet there is a contradiction between the inviting picturesqueness of the interior photos and the way the exhibition is organized. The visitor must work hard to grasp the richness of 35 years of work by the artist, in the context of the contents of his legacy, which covers the walls, and in the context of the jewelry of his contemporaries. It is especially difficult because the visitor is not facilitated with a lot of supporting explanatory material. Yet this is one of the most interesting jewelry exhibitions I have seen recently.

Manfred Bischoff died March 30, 2015, at the age of 67, after a long period of declining health. Wolfgang Lösche, the director of the Handwerkskammer, explains that the exhibition is the realization of a long-existing wish to exhibit Bischoff’s work in Munich—sadly it could only be organized after his death. The exhibition is based on Bischoff’s estate, extended with loans from private and museum collections, and was curated by Lösche, Angela Bock (also from the Handwerkskammer), and Rike Bartels, Bischoff’s heir, friend, and companion in life for some time.[1]

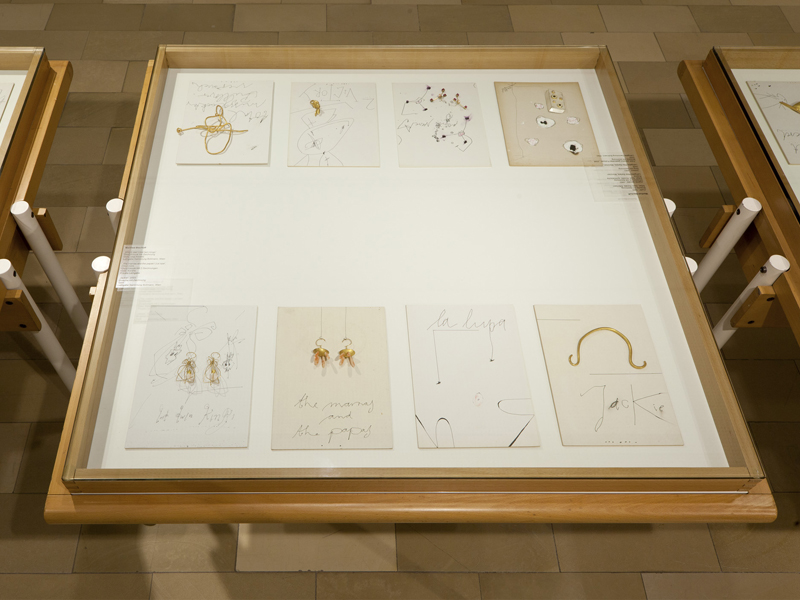

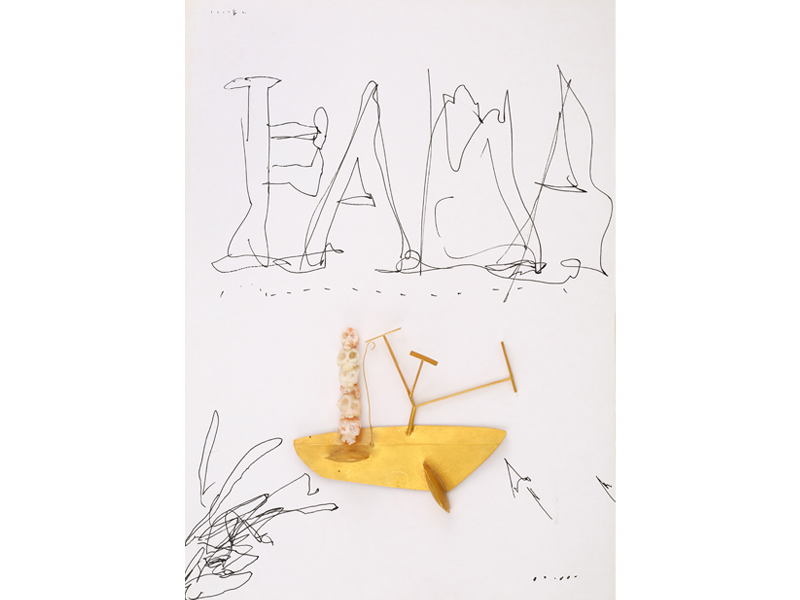

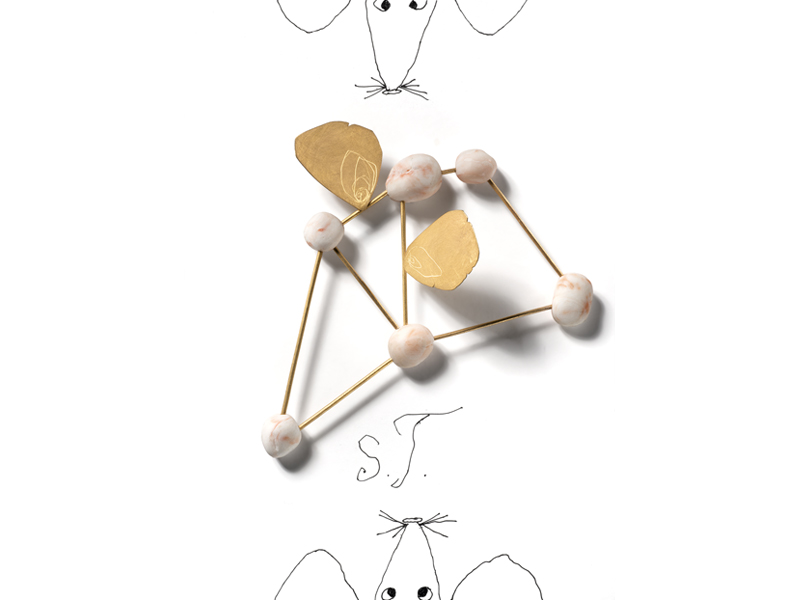

The exhibition includes many related drawings and the work with which he made his name, the majority on loan from private collectors. (Among these are Mr. and Mrs. Bollmann, who were his most generous supporters. They visited the artist regularly and over the decades acquired an extensive collection of jewelry and drawings from him.) The drawings offer an additional underlying layer to the jewelry—humorous, poetic, philosophical, intellectual, and often intriguingly mysterious. “The exit is at the entrance” is one of those compelling texts written down in his characteristic handwriting. Bischoff is the only artist in jewelry who worked like this, employing his double talent as a fine artist and a goldsmith, a very capable artist of drawings and someone who could form gold into the most unusual shapes. He was at once an artist with an enigmatic imagination, a poet, an intellectual, and a skilled craftsman.

Exhibited are magisterial works, such as Hugo Perché? (2012), its big golden bird body seemingly alive, and M.F., Bischoff’s interpretation in gold of a knitted finger puppet of Michel Foucault by the Unemployed Philosophers Guild from Brooklyn, New York. I Represent Art; What Do You Represent? is the title of a gold and coral ring from 2009 that must be a great joy for the wearer because it provides the best possible answer to people’s questions. His jewelry and drawings made in the years around the turn of the century, such as Baghdad Sub Rose (1999), with its color explosion, and Madonna del Parto (2002), with the sharp cut in the belly, seem extremely vehement compared to earlier and later work. Especially if one realizes that these are brooches, an object type that Bischoff preferred because of its confrontational character.[2]

As I pointed out before, it is not an easy exhibition. The visitor is not taken by the hand along a neatly organized chronological tour, from one milestone to the other. Instead, the organizers of the exhibition emphasized the contingencies of life, including less known early work, detours, and exercises. Art history likes to pretend that an artist’s oeuvre consists of a number of successive chronological periods culminating in the ultimate characteristic “ripe” style of the artist but, in reality, creating art is a matter of searching after something unknown within the context of your time, place, and environment. The Munich exhibition clearly wants to stress this aspect.

The work of 17 contemporary artists who were invited to make a tribute to Manfred Bischoff is found dispersed in various showcases on the ground floor and in the basement. Other jewelry from these artists is also exhibited—which is rather confusing, especially for the uninitiated visitor. On the other hand, each showcase can be enjoyed singly to discover finally that they can be observed as islands in an archipelago—they belong together but they have their own atmosphere and character. Together they present the world of German (and related European) jewelry in the last part of the 20th and the early part of the 21st century. The exhibition is not just a tribute to Bischoff or a retrospective of his work but also establishes an introduction to German jewelry in the last decades of the 20th century. It takes some time and knowledge to recognize this subtheme in the exhibition, however.

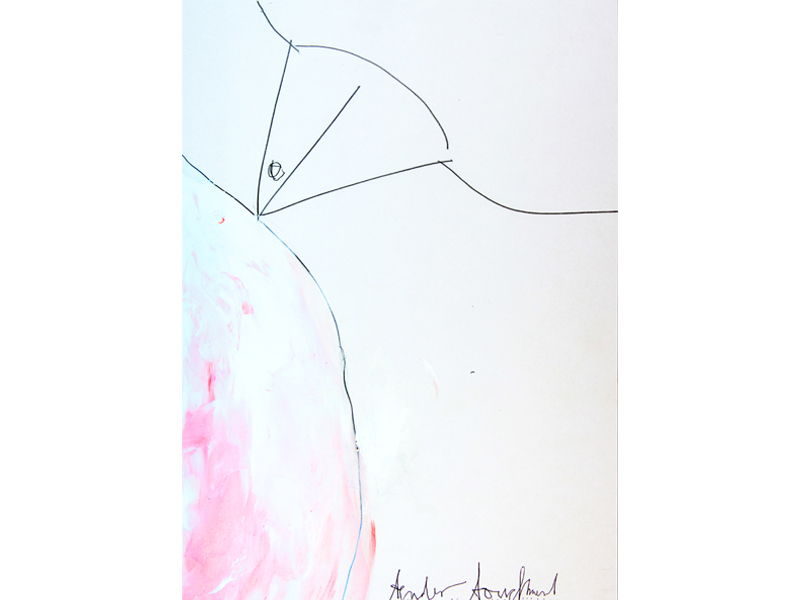

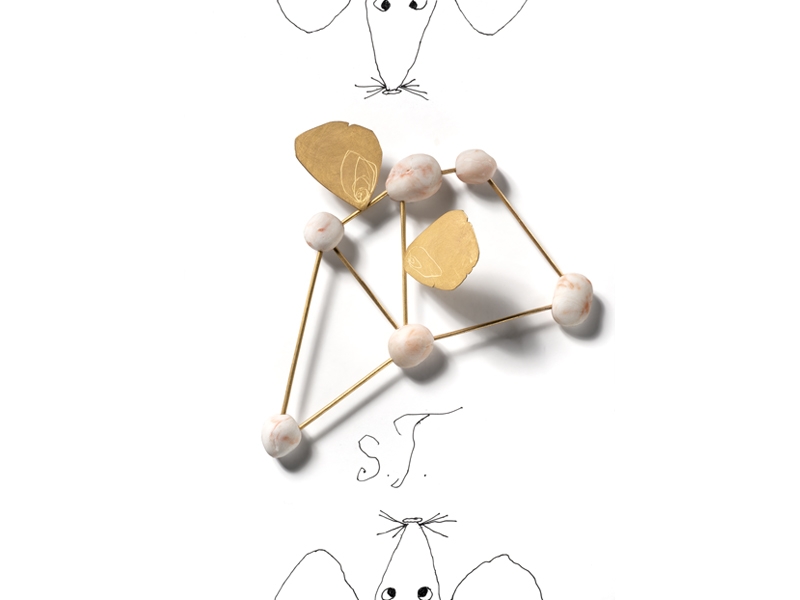

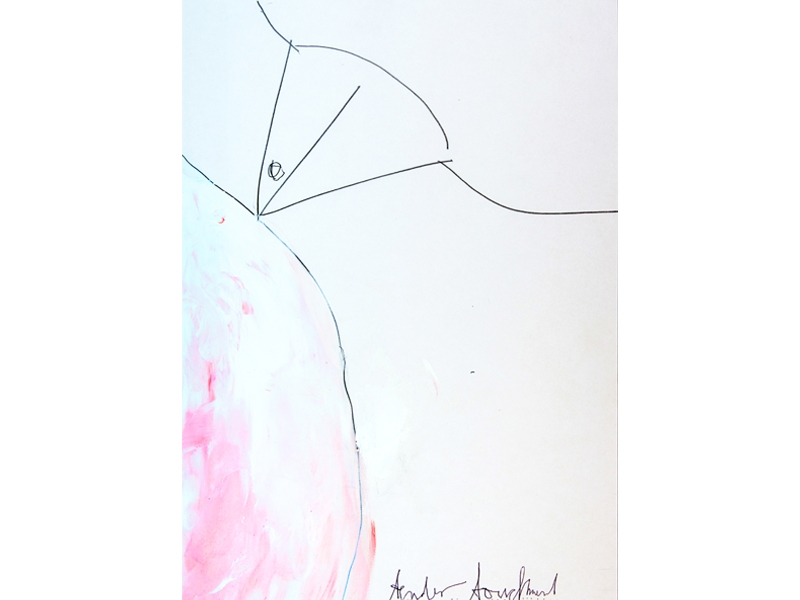

Some artists managed well in making a tribute to Bischoff. Francesco Pavan contributed two raised gold brooches in Bischoff’s preferred intense high-karat gold, a tower (Torre, 2016–2017), and a cube (Omaggio a Manfred, 2016–2017). The tower recalls drawings and jewelry by Bischoff about the “home,” but the square is a puzzling piece. However, knowing that Pavan initially wanted to call this work Anatra Cubista (cubic duck) turns it into a moving response from the master of Italian geometry to the malleable imagery of Bischoff. Peter Skubic’s brooch Der Tote Manfred (2016), a mirrored head with two big eyes, as if a death mask, expresses friendship and sorrow about Bischoff’s death. The brooch is exhibited in a showcase together with two early brooches by Bischoff from 1983, both showing an image (by Gabi Dziuba) of the artist as a cheerful young man with a paper hat and a funnel on his head. The dialogue between these pieces, spanning a lifetime, is magnificent. Robert Smit took a Bischoff drawing entitled Tender Touchment as his inspiration. The Tender Touchment drawing (in another showcase) shows how two forms, a pink, fleshy rounded one and a pointed one, gently touch each other through the end of the pointed form. Smit immediately thought about the touching of metal, which always leaves a mark no matter how gentle the touch. Inspired by Bischoff’s words, he took his preferred material, a sheet of tin, and made impressions of fingermarks on the tin sheet using a printing technique. The examples show a deeply felt congeniality between the artists and Bischoff.

Among the Bischoff jewelry made in the early 1980s are nice examples of postmodernist jewelry, representing gemstones by sculpting a foam material and painting it to suggest the shine of gems, or neo-classicist motifs such as the fluted column. Other brooches from this period show his interest in pictorial space, combining various precious materials with nonjewelry materials (a photo, a piece of plastic, or pencil drawings) in one piece, to create a layered image that suggests movement.

It is fascinating to observe how drawing, painting, words, and jewelry, all visual resources he mastered, are accumulated in one piece. l’Annunziazone (1980) for instance, is a brooch sculpted in foam which was then painted and drawn with an image of a cornice and a flame—the title is hand written on the lower part. In early work he stacked the visual resources on top of each other: sculpting, painting/drawing, and title/text all appear on top of each other in a piece. Some 10 years later, he was separating these elements so that on the one hand he was producing jewelry, while on the other he combined painting, drawing, and writing into his two-dimensional work.

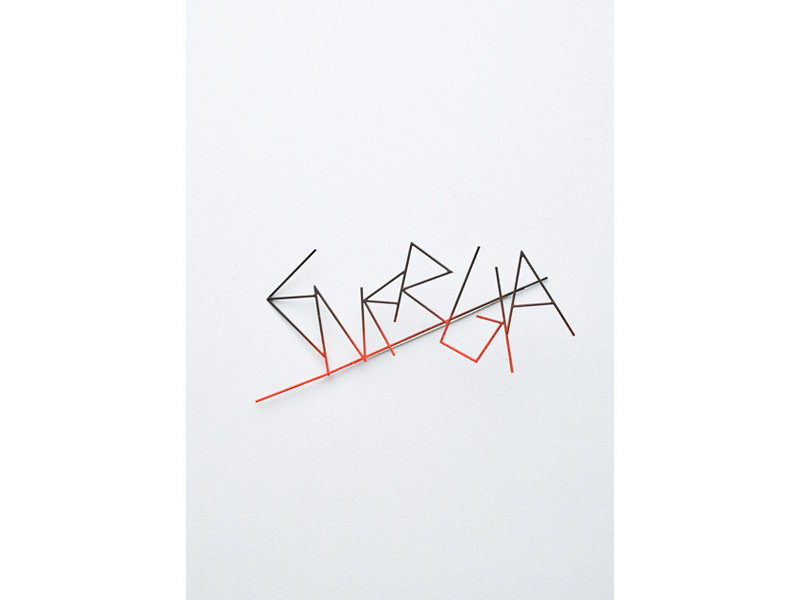

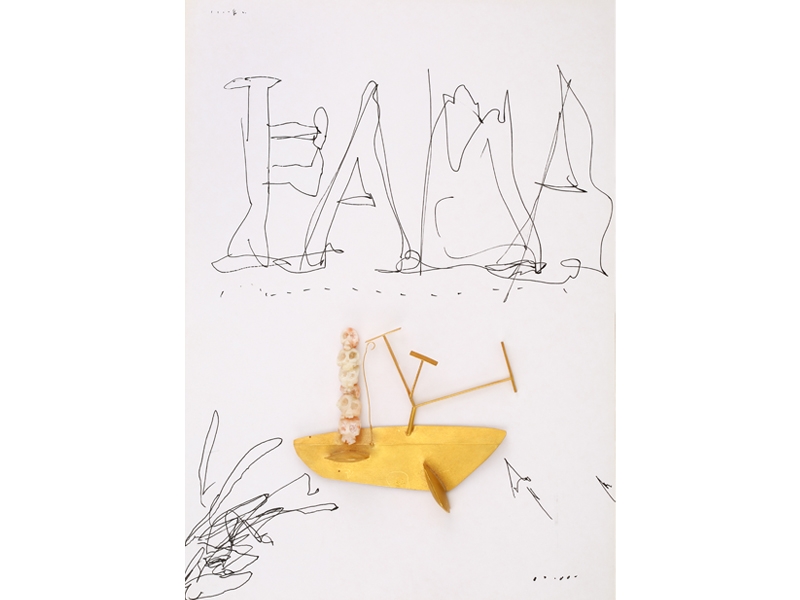

In German goldsmithing, the use of nonjewelry-based materials was still questionable in the early 1980s. But in this period Bischoff was obviously influenced by the “wilden Malerei” (the “wild painting,” the “new wild”), a neo-Expressionist style that came up around 1980 in Germany, Italy (Young Italians), and other countries. German painters such as Georg Baselitz and A.R. Penck, Italians like Sandro Chia and Enzo Cucchi, and American artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle have been included in this art movement. In their vehement painting they turned against the established order, and Bischoff found his own variation in jewelry. “NO” says a simple brooch bent from steel wire and painted in red glow-in-the-dark paint. Another brooch, also made from steel wire, expresses the word “ENERGIA,” with the letters restlessly sticking to each other as if to materialize the notion. Both brooches were made in 1982, as were the earrings featuring crude drawings of heads made from steel wire with a text on each piece, “Luxus” for one ear and “No” for the other. This kind of work is reminiscent of graffiti and the way the Berlin wall was used as a canvas for artistic and political expression. In the period 1980 to 1984, Bischoff lived in Berlin, sharing a studio with Georg Dobler, whose wire jewelry is well represented in the exhibition. Other artists had their studios in the same building, and there was also an architectural firm and a shop for building materials. To earn some money, Bischoff and Dobler sometimes built models for the architects. In this way, Bischoff discovered materials and techniques which eventually resulted in jewelry made from foam, sprayed with special paints. His stay in Berlin declares the evident urban character of this jewelry.

In 1984, when Bischoff gained a DAAD stipend, he moved to Italy, and there his jewelry began to change: Gold slowly entered his work. And finally, around 1990, raised figures in vibrant gold invigorated by sensuous pink coral details became his method of expression in jewelry, punctuated by drawings and texts.

The many drawings on the walls give away fragments of his intellect and inner life, portraits of people—Michel Foucault, Freud, Joseph Beuys, Samuel Beckett, Voltaire, John Cage—animals, sole words in capitals (ANTI GONE gains a new meaning through the way the letters are distributed on the paper), all done with a searching yet sure touch. And there is more—the serious start of an archive of work initiated by Bischoff himself in the 1990s, and the newspaper clippings, invitations, and images described with comments, annotations, words, and drawings as found on his desk in his house. Among other pieces in a showcase downstairs is also his last unfinished piece—a big golden blob on a photocopy of a drawing of a woman with spread legs.

The organizers of the exhibition have scrutinized each piece by Bischoff, and every drawing, note, and sketch, finding elements of imagery that could be highlighted and confronted with work by other other artists. Surprisingly, an ancient wooden beam, a found object that decorated the wall of his house, set upright against the wall on the ground floor, recurs in his jewelry and drawings as a tower-like house. The handle of a bucket, hung next to the old beam, returns in a drawing and a brooch executed in gold, entitled Jackie (2003). A nice bonus is to find a similar bucket handle as an element in a necklace by Hermann Jünger, made almost 30 years earlier, in 1975. The difference is also noteworthy: Bischoff uses the handle upright, giving the ends a charming outward curl in a cartoon-like way, while Jünger hangs the golden handle upside down from two silver chains as a strange pendant. Some showcases downstairs illustrate how Bischoff, as a student in Jünger’s class , experimented with metalworking techniques introduced by his Japanese classmate Erico Nagai. Here the visitor can also discover that the early Bischoff is indebted to Jünger and Dobler.

In conclusion, this exhibition celebrates Bischoff’s imagination, his wish to evade interpretation, and the freedom of creation. In a way, the organizers even started to produce their own creations as they made associations: Skubic’s death mask paired with two self-portraits by Bischoff, Smit’s Madonna della Dolomiti with a wire face brooch by Bischoff, or Kadri Mälk’s silver angel with Bischoff’s tormented self-representation in rich gold and pink coral. The visitor can choose. One can focus on the jewelry and drawings by Bischoff, get under the spell of his sculptural and imaginative talent, and be seduced by the yellow burning gold and the soft pink coral. Or one can start searching for meaning, for connections, for chronology. The exhibition has many layers and stories, and is an unusual one, confusing at some points, but also the best tribute Manfred Bischoff could have received.

Tributo a Manfred Bischoff

La Salida está en la entrada

Manfred Bischoff, Homenaje a Manfred Bischoff

9 de marzo – 8 de abril de 2017

Galería Handwerk, Múnich, Alemania

La primera impresión de la exposición Tributo a Manfred Bischoff está dominada por las grandes fotografías de las paredes del espacio de exposición Handwerkskammer en Múnich. Ahí se muestra el interior del antiguo convento capuchino en San Casciano dei Bagni, Italia, donde el artista alemán vivió desde 2000 hasta su muerte. Las imágenes son una bienvenida acogedora porque dan la ilusión de entrar en el espacio personal de alguien, aunque existe una contradicción entre la atracción pintoresca de las fotos interiores y el modo en que se organiza la exhibición. El visitante debe trabajar duro para captar la riqueza de los 35 años de trabajo del artista, en el contexto del contenido de su legado que cubre las paredes, y en el contexto de la joyería de sus contemporáneos. Es especialmente difícil porque al visitante no se le proporciona material aclaratorio de apoyo. Sin embargo, esta es una de las exposiciones de joyería más interesantes que he visto recientemente.

Manfred Bischoff murió el 30 de marzo de 2015, a la edad de 67 años, después de un largo período en el que su salud iba decayendo. Wolfgang Lösche, el director del Handwerkskammer, explica que la exposición es la realización de un deseo ya existente de exhibir la obra de Bischoff en Múnich que lamentablemente sólo pudo organizarse después de su muerte. La exposición se basa en la propiedad de Bischoff, ampliada con préstamos de colecciones privadas y de museos, la curaduría fue realizada por Lösche, Angela Bock (también del Handwerkskammer) y Rike Bartels, heredero de Bischoff, amigo y compañero de vida durante algún tiempo. [1]

La exposición incluye muchos dibujos relacionados y el trabajo con el que hizo su nombre, la mayoría prestados por coleccionistas privados. (Entre ellos el Sr. y la Sra. Bollmann, quienes fueron sus partidarios más generosos, visitaron al artista con regularidad y a lo largo de décadas adquirieron una extensa colección de joyas y dibujos de él). Los dibujos ofrecen una capa subyacente adicional a la joyería- humorística, poética, filosófica, intelectual, y a menudo intrigantemente misteriosa. “La salida está en la entrada” es uno de esos textos persuasivos escritos en su característica caligrafía. Bischoff es el único artista de la joyería que trabajó de esta manera, empleando su doble talento como buen artista y orfebre, un muy capaz dibujante y alguien que podría formar el oro en las formas más inusuales. Era a la vez un artista con una imaginación enigmática, un poeta, un intelectual y un hábil artesano.

Se exhiben obras magistrales como ¿Hugo Perché? (2012), su gran cuerpo de ave de oro aparentemente vivo, y M.F., la interpretación de Bischoff en oro de una marioneta de dedo tejida de Michel Foucault por el Colegio de Filósofos Desempleados de Brooklyn, Nueva York. Yo represento el arte; ¿Qué representas? Es el título de un anillo de oro y coral de 2009 el cual deber ser una gran alegría llevar puesto porque proporciona la mejor respuesta posible a las preguntas de la gente. Sus joyas y dibujos realizados en los años de finales de siglo, como Baghdad Sub Rose (1999), con su explosión de color, y Madonna del Parto (2002), con el corte agudo en el vientre, parecen extremadamente vehementes en comparación con trabajos anteriores y posteriores. Especialmente si uno se da cuenta de que son broches, un tipo de objeto que Bischoff prefirió debido a su carácter confrontador. [2]

Como señalé antes, no es una exposición fácil. El visitante no es llevado de la mano a lo largo de un recorrido cronológicamente bien organizado, de un hito a otro. En cambio, los organizadores de la exposición hicieron hincapié en las contingencias de la vida, incluyendo los primeros trabajos menos conocidos, los desvíos y los ejercicios. A la historia del arte le gusta fingir que la obra de un artista consiste en una serie de períodos cronológicos sucesivos que culminan en el último estilo característico “maduro” del artista pero, en realidad, crear arte es un asunto que consiste en buscar algo desconocido dentro del contexto de su tiempo, lugar y entorno. La exposición de Múnich claramente quiere destacar este aspecto.

El trabajo de 17 artistas contemporáneos que fueron invitados a hacer un homenaje a Manfred Bischoff se encuentra disperso en varias vitrinas en la planta baja y en el sótano. Otras joyas de estos artistas también se exhiben, lo que es bastante confuso, especialmente para el visitante no iniciado. Por otro lado, cada vitrina se puede disfrutar por separado para descubrir finalmente que pueden ser observadas como islas en un archipiélago- están juntas pero tienen su propia atmósfera y carácter. Juntas presentan el mundo de la joyería alemana (y europea) en la última parte del vigésimo y la primera parte del siglo XXI. La exposición no es sólo un homenaje a Bischoff o una retrospectiva de su obra sino que también establece una introducción a la joyería alemana en las últimas décadas del siglo XX. Sin embargo, se necesita cierto tiempo y conocimiento reconocer este subtema en la exposición.

Algunos artistas lograron hacer un homenaje a Bischoff. Francesco Pavan contribuyó con dos broches en el oro intenso preferido de Bischoff, Una torre (Torre, 2016-2017) y Un cubo (Omaggio a Manfred, 2016-2017; Homenaje a Manfred 2016-2017). La torre recuerda dibujos y joyas de Bischoff sobre el “hogar”, pero el cubo es una pieza desconcertante. Sin embargo, sabiendo que Pavan inicialmente quería llamar a este trabajo Anatra Cubista (Pato Cubista) lo convierte en una respuesta móvil del maestro de la geometría italiana a la imaginería maleable de Bischoff. El broche de Peter Skubic Der Tote Manfred (2016), una cabeza reflejada con dos grandes ojos, como si fuera una máscara de muerte, expresa amistad y pesar por la muerte de Bischoff. El broche se exhibe en un mostrador junto con dos broches tempranos de Bischoff de 1983, ambos muestran una imagen (por Gabi Dziuba) del artista como un hombre joven alegre con un sombrero de papel y un embudo en su cabeza. El diálogo entre estas piezas, que abarca toda una vida, es magnífico. Robert Smit tomó un dibujo de Bischoff titulado Tender Touchment como su inspiración. El dibujo de Tender Touchment (en otra vitrina) muestra como dos formas, una rosada, carnosa redondeada y una puntiaguda, se tocan suavemente por el extremo de la forma puntiaguda. Smit inmediatamente pensó en el toque de metal, que siempre deja una marca sin importar lo gentil del contacto. Inspirado por las palabras de Bischoff, tomó su material preferido, una hoja de estaño, e hizo impresiones de huellas dactilares en la hoja de estaño usando una técnica de impresión. Los ejemplos muestran una simpatía profundamente sentida entre los artistas y Bischoff.

Entre las joyas de Bischoff hechas a principios de los años 80 se encuentran ejemplos de piezas posmodernas, que representan piedras preciosas esculpidas en un material de espuma y pintándolo para sugerir el brillo de gemas o motivos neoclásicos como la columna estriada. Otros broches de este período muestran su interés por el espacio pictórico, combinando diversos materiales preciosos con materiales no tradicionales de la joyería (una foto, una pieza de plástico o dibujos a lápiz) en una sola pieza, para crear una imagen en capas que sugiere movimiento.

Es fascinante observar cómo el dibujo, la pintura, las palabras y las joyas, todos recursos visuales que dominó de forma magistral, se acumulan en una sola pieza. L’Annunziazone (1980), por ejemplo, es un broche esculpido en espuma que luego fue pintado y dibujado con una imagen de una cornisa y una llama -el título está escrito a mano en la parte inferior. En trabajos tempranos apiló los recursos visuales uno encima de otro: la escultura, la pintura / el dibujo, y el título / el texto aparecen todos yuxtapuestos en una pieza. Unos diez años más tarde, separaba estos elementos para que por un lado estuvieran produciendo joyas, mientras que por el otro combinaba la pintura, el dibujo y la escritura en su trabajo bidimensional.

En la orfebrería alemana, el uso de materiales no tradicionales de la joyería era todavía cuestionable a principios de los años ochenta. Pero en este período Bischoff fue obviamente influenciado por el “wilden Malerei” (la “pintura salvaje”, el “nuevo salvaje”), un estilo neo-expresionista que surgió alrededor de 1980 en Alemania, Italia (jóvenes italianos) y otros países. Los pintores alemanes como Georg Baselitz y A.R. Penck, italianos como Sandro Chia y Enzo Cucchi, y artistas estadounidenses como Julian Schnabel y David Salle han sido incluidos en este movimiento artístico. En su vehemente pintura se volvieron contra el orden establecido y Bischoff encontró su propia variación en la joyería. “NO” dice un simple broche doblado de alambre de acero y pintado en rojo brillo en la pintura oscura. Otro broche, también hecho de alambre de acero, expresa la palabra “ENERGIA”, con las letras pegadas incesantemente unas a otras como para materializar la noción. Ambos broches se hicieron en 1982, al igual que los pendientes con dibujos en bruto de cabezas hechas de alambre de acero con un texto en cada pieza, “Luxus” para una oreja y “No” para la otra. Este tipo de trabajo es una reminiscencia de los grafiti y la forma en que el muro de Berlín fue utilizado como un lienzo para la expresión artística y política. En el período de 1980 a 1984, Bischoff vivió en Berlín, compartiendo un estudio con Georg Dobler, cuya joyería de alambre está bien representada en la exposición. Otros artistas tenían sus estudios en el mismo edificio, y también había una empresa de arquitectura y una tienda de materiales de construcción. Para ganar algo de dinero, Bischoff y Dobler a veces construían modelos para los arquitectos. De esta manera, Bischoff descubrió materiales y técnicas que eventualmente resultaron en joyas hechas de espuma plástica, rociadas con pinturas especiales. Su estancia en Berlín declara el evidente carácter urbano de esta joyería.

En 1984, cuando Bischoff ganó una beca del DAAD, se trasladó a Italia, y allí sus joyas comenzaron a cambiar: el oro lentamente entró en su trabajo. Y, por último, alrededor de 1990, las figuras elevadas en vibrante oro reforzadas por los sensuales detalles de coral rosa se convirtieron en su método de expresión en joyería, intervenidas por dibujos y textos.

Muchos dibujos en las paredes regalan fragmentos de su intelecto y vida interior, retratos de personas -Michel Foucault, Freud, Joseph Beuys, Samuel Beckett, Voltaire, John Cage -animales, palabras únicas en mayúsculas (ANTI GONE gana un nuevo significado a través de la forma en que las cartas se distribuyen en el papel), todo hecho con un toque de búsqueda, pero seguro. Y hay más: el comienzo serio de un archivo de trabajo iniciado por el propio Bischoff en los años noventa y los recortes de periódicos, invitaciones e imágenes descritos con comentarios, anotaciones, palabras y dibujos que se encuentran en el escritorio de su casa. Entre otras piezas ubicadas en una vitrina de un nivel inferior también está su última pieza inacabada: una gran gota dorada en una fotocopia de un dibujo de una mujer con las piernas separadas.

Los organizadores de la exposición han examinado cada pieza de Bischoff y cada dibujo y nota, encontrando elementos de imágenes que pueden ser destacados y confrontados con el trabajo de otros artistas. Sorprendentemente, una viga de madera antigua, un objeto encontrado que adornaba la pared de su casa, colocada en posición vertical contra la pared de la planta baja, se repite en sus joyas y dibujos como una casa en forma de torre. El mango de una cubeta, colgado al lado de la antigua viga, regresa en un dibujo y un broche ejecutado en oro, titulado Jackie (2003). Un bonito extra es encontrar un mango de cubeta similar a un elemento en un collar de Hermann Jünger, hecho casi 30 años antes, en 1975. La diferencia también es digna de mención: Bischoff utiliza el mango en posición vertical, dando a los extremos un rizo encantador hacia fuera de una forma similar a una caricatura, mientras que Jünger cuelga el mango de oro al revés de dos cadenas de plata como un extraño colgante. Algunas dispositivos ilustran cómo Bischoff, como estudiante en la clase de Jünger, experimentó con las técnicas metalúrgicas introducidas por su compañero de clase, el japonés Erico Nagai. Aquí el visitante también puede descubrir que el temprano Bischoff está en deuda con Jünger y Dobler.

En conclusión, esta exposición celebra la imaginación de Bischoff, su deseo de evadir la interpretación, y la libertad de creación. En cierto modo, los organizadores comenzaron incluso a producir sus propias creaciones al hacer asociaciones: la máscara de muerte de Skubic empatada con dos autorretratos de Bischoff, La Madonna della Dolomiti de Smit con un broche de Bischoff o El ángel de plata de Kadri Mälk con las atormentadas auto-representación de Bischoff en oro vibrante y coral rosa. El visitante puede elegir: puede centrarse en la joyería y los dibujos de Bischoff, caer bajo el hechizo de su talento escultórico e imaginativo, y ser seducido por el oro amarillo quemante y el coral rosa suave; o puede comenzar a buscar significados, conexiones, cronologías. La exposición tiene muchas capas e historias, y es inusual, confusa en algunos puntos, pero también el mejor homenaje que Manfred Bischoff pudo haber recibido.

[1] Alexandra Bahlmann organizó la exposición.

[2] Catálogo de la exposición, Manfred Bischoff, Museo Isabella Stewart Gardner, Boston, 2002, p.13: “Los broches se sienten mucho más en casa en el cuerpo, porque no se pueden ocultar. Los pendientes los puedes esconder. Un anillo lo puedes ocultar. Pero un broche es una confrontación.”

Liesbeth den Besten es una historiadora del arte, residenciada en Ámsterdam, que trabaja como escritora independiente, profesora, conferenciante y curadora. Actualmente, enseña historia de la joyería en Sint Lucas Antwerpen. Es presidenta de la Fundación Françoise Van Den Bosch para la joyería contemporánea, miembro del consejo asesor de la Chi ha paura …? Fundadora y miembro fundador de Think Tank, una iniciativa europea para las artes aplicadas. Su libro, On Jewellery: A Compendium of International Contemporary Art Jewellery, fue publicado por Arnoldsche en noviembre de 2011.

Translated from English by Andreína Rodriquez, with support from Barbara Magaña and Marina Acosta.