Daniel Kruger: Jewellery and Ceramics 1974–2014

October 17, 2015–January 24, 2016

Stedelijk Museum ’s-Hertogenbosch, Holland

Daniel Kruger has been around for a long time, he is an inspiration for younger jewelry artists, and he has been the Professor for jewelry at Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule, in Halle (Germany) since 2005. Now there is finally an overview of his work, in the form of an exhibition and a publication. The invitation card for the opening of the large overview exhibition, Daniel Kruger: Jewellery and Ceramics 1974–2014, at the Stedelijk Museum in ’s-Hertogenbosch, is rather singular. It shows a person wearing a crocheted white Doily, adorned with red and blue glass beads on the edges, over his/her (?) head. Not a very typical Daniel Kruger piece, I would say, but definitely an image that doesn’t let go. Kruger once made it for the Gallery Ra jubilee exhibition Masquerade, organized in 2002. The accompanying text, “Does it keep you in or does it keep them out” could be interpreted as a statement.

Yet Daniel Kruger (born in 1951, in Cape Town, South Africa) is not a jeweler of statements. He is not a revolutionary, and not an iconoclast, but his jewelry has been opening up new horizons continuously from the mid-1970s up ’til now. An artistic practice of four decades was the reason for making a traveling exhibition and a book. The Dutch museum is the last stop of an exhibition tour that started at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Leipzig, Germany, and then traveled to the Goldschmiedehaus in Hanau, Germany.

Yet Daniel Kruger (born in 1951, in Cape Town, South Africa) is not a jeweler of statements. He is not a revolutionary, and not an iconoclast, but his jewelry has been opening up new horizons continuously from the mid-1970s up ’til now. An artistic practice of four decades was the reason for making a traveling exhibition and a book. The Dutch museum is the last stop of an exhibition tour that started at the Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Leipzig, Germany, and then traveled to the Goldschmiedehaus in Hanau, Germany.

Although many jewelry lovers are unaware of it, and despite his low profile in the ceramics world, Daniel Kruger is a double talent—he is both jeweler and ceramicist. The publication Daniel Kruger—Between Nature and Artifice (Arnoldsche, 2014) only covers jewelry, but the Grassi Museum and the Stedelijk Museum ’s-Hertogenbosch rightly decided to show both artistic sides of this prolific artist. The Dutch museum was able to draw from its extended collection of Kruger ceramics, acquired since the 1980s, and courageously displayed jewelry and ceramics intermingled. This is not the easy way: It forced the curators to use their imagination and to dig up connections, contrast, and dialogues. The idea of blending, of finding kinships in form, pattern, color, texture, and theme, which also structures the jewelry in the publication, is intensified by the totally transparent display of the work in randomly stacked Perspex cases.

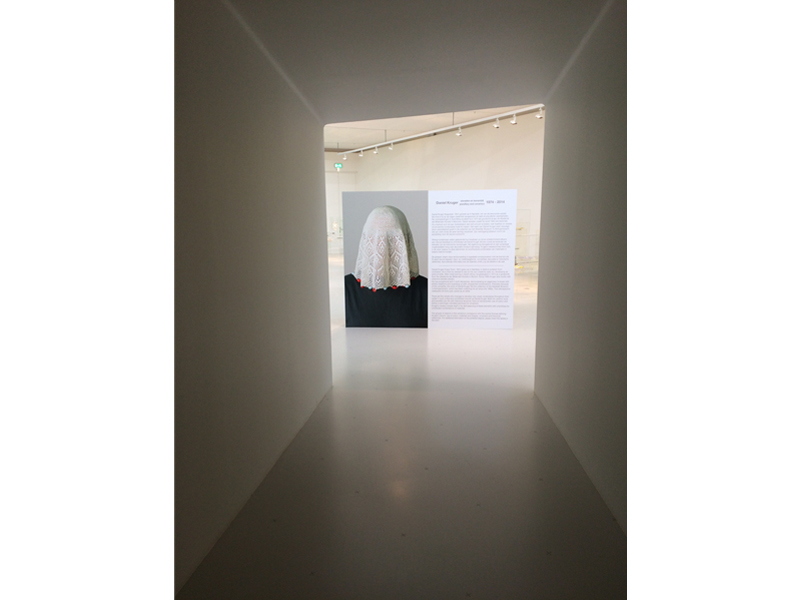

The first encounter with Kruger’s work is a wall standing opposite the entrance of the museum room, where a huge photo with the Doily-masked person attracts all the attention (on the other side of the wall, a huge showcase is used for showing the real piece). Behind the wall, a spacious and light-filled room opens up, in which constellations of totally transparent cases are scattered in the space—completely different from what we are used to in “jewelry-land.” The museum decidedly moved far away from the shrine-like treasure rooms, or austere modernist showcase displays that define usual jewelry presentations. As part of the construction of a new museum building that opened its doors in May 2013, two designers, Niels van Eijk and Miriam van der Lubbe, were commissioned to create this display system for jewelry and ceramics. The simple and flexible system of Perspex cases of different sizes can easily be changed and repositioned according to what is needed. This does not serve every jewelry display, but in the case of Daniel Kruger’s exhibition it is a happy marriage.

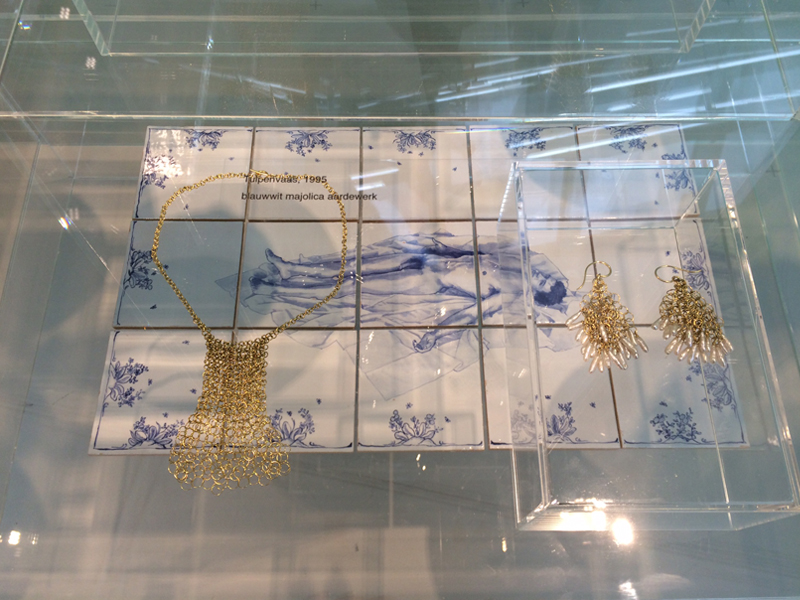

The see-through effect of this display might be distracting at some points, but it also provides wonderful new insights. There is for instance a bottom case that shows a ceramic Delft blue tableau composed of 15 square tiles showing a reclining, naked young man—the ceramic composition is framed with floral ornaments along the edges of the outer tiles. Seeing this tableau through the case that sits on top of it gives a completely different view than looking at it from the opposite side through another case with different jewelry in it, either stressing the ornamental character of a group of five charming golden brooches or pointing to the construction of a necklace with five balls that are put together from small parts. Another advantage of the transparent stacked cases is that anyone who is interested can have a look from below, which is always revealing when observing jewelry, but especially in the case of Kruger’s pieces. Sitting on your knees, looking up into the showcase, will give you a rare insight into his excellent craftsmanship down to the smallest details. For instance, you’ll discover the construction underneath a typical Kruger pendant consisting of five enameled discs, and how the geometrical bearing construction enables the discs to move freely.

The exhibition is made up of five groups—form, historical references, material, decoration and ornament, and color—but does not spell out clear boundaries between one group or another The themes should be considered rather as guidelines for looking at the work. There’s no need to go to ’s-Hertogenbosch for an art-historical or stylistic account of Daniel Kruger’s work. Anyone who knows the work of the artist, and has followed it for some time, will agree that his work is an art-historical enigma. Kruger switches easily from one theme to another, or from one style to another—his development is circular rather than linear. There is a huge difference between his first, rather cautious, jewelry made at the end of the 1970s and the outburst of expression in his later work. But there are also connecting features, such as the use of textile and crochet techniques, which are inspired by his youth in Namibia, Africa. A group of pendants from 1976–1979 have a rather tribal character: One necklace contains a glass holder with herbs, while the crocheted part has long, loose hanging threads. More recent brooches, in the form of soft bags and made from coral beads, stone fragments, or lemon seeds, knotted on silk, have a similar ethnic origin and expression (even though the later work has become much more expressive).

For want of clear beginnings, or ends, his work shows some “periods”: Metal prevailed in Kruger’s work from the 1970s until the mid-1990s, resulting for instance in austere and powerful brass bracelets (1983), baroque silver brooches based on frills and bows (1993), and refined brooches of gold lace work embellished with precious stones, which are inspired by Rococo ornaments—the so-called Devant de Corsage (1995). From then on, Kruger developed into an inspired colorist. He rapidly extended his range of materials with silk threads in vibrant colors, glass beads, red coral, Perspex and stones, amber, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Fimo clay, and small fragments of colored stones. His palette became more intense when he started using pigments and enamel in 2006. In more recent years, ornamental discs literally became palettes of matching colors—bright, uniform, patterned, and splattered, on even and on textured surfaces. But we have to be cautious, because Kruger is not a man who takes a linear path, and so in 2010, for instance, he made a series of textured silver necklaces that undermine the development just outlined.

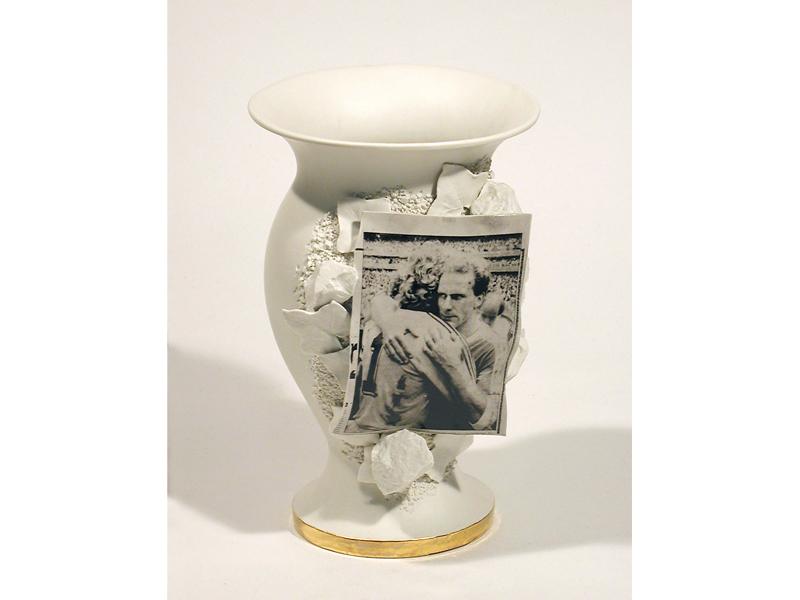

In Kruger’s vases, vessels, and tile tableaus, male models in various postures and athletic wear (mostly soccer or swimming skirts) are often used as an ornament, combined with another layer of floral or natural ornaments (oranges, shells, branches with leaves) that creates interesting confrontations. In this play with ornament, Kruger is at his best. His models are based on magazine and newspaper images, hand painted or applied with the help of transfers. They don’t have a heroic appeal and some even look lost sitting with their football amidst floral ornamental motives. Conversely, there is a vase with four panels around it, showing four young men holding a camera self-timer for a full-size naked self-portrait—and here the models look quite self-aware. Kruger’s imagery is ambiguous, and hovers between humor and soft gay porn.

Sometimes ceramic photographs with curled edges adorn the body of a vase, while a piece of ceramic coral or a shell seems to hold the photo. Here the ornament is used in its purest form, to support and to symbolize. Kruger is aware of the position of the applied arts within the still existing hierarchy of the arts, and his celebration of the ornament is a liberating act. In Kruger’s hands, anything can become an ornament, either an ornament on ceramic tableware, or a piece of jewelry. The switching between ceramics and jewelry informs his work in both directions: Kruger uses formal strategies associated with jewelry, such as handwritten (male) names to adorn a series of elegant pink glazed plates, and small portrait color photographs to decorate a vase all around—in general names and little portraits have the function to remember or to express love, functions that are usually performed by jewelry. In his jewelry, the superimposing of an ornament on top of another ornament might be inspired by the ceramic decorative tradition, as for instance in Delft blue ceramics.

Both liberating and humorous is Kruger’s ability to reference sexuality, turning balls into soft, malleable, and colorful ornaments that beg to be touched and felt. As a brooch or as a necklace, they create a strong effect when worn, enhanced by the flawless positioning of his jewelry on the body. They cause the right effect without wanting to shock. Instead his work is full of mischief.

The exhibition makes clear that Kruger already at an early stage moved freely between different cultures, as a true cosmopolite. A good example is the 1978 necklace consisting of colored plastic forks for eating chips, combined with found metal objects, on a silver beaded string. There is a strong ethnic aspect to it, but it is also connected with Herman Jünger’s (Kruger’s professor at the Munich Academy) jewelry of that time, while it also bonds with the international ready-made, new jewelry strategies that were adopted by many of his Dutch and English contemporaries. Daniel Kruger feels at ease with European as well as African culture, with precious as well as found materials, with natural as well as man-made materials, with filigree as well as crochet, with symmetry as well as organic forms, and with lavish historical ornament as well as graphic color fields. Kruger’s work, both jewelry and ceramics, is a celebration of the ornament. And Kruger deals with this in a very smart and witty way.

In the introduction to his publication, Kruger writes about his impressions of nature in southern Namibia by describing its aridness, the intense color of the moon, the skies and the hazy horizon, and the sudden outburst of colors after some rainfall. “Uncountable nuances of colours and patterns and textures in stones and plants. In a landscape like this there is no such thing as old and new. It is a spiritual space outside of time.”1 There is such a deep longing in these words that it leads you to think that Daniel Kruger is trying to revive in his jewelry this magical place time and again. His jewelry exists in equilibrium—regardless of changes of style or material, it is always personal. Without using any titles, and without an obvious underlying philosophy or narrative, Kruger’s jewelry is accessible to anyone, and to many interpretations. Within the realm of jewelry he is one of the most mysterious, elusive characters. The moment you think you understand him, he has already made up something completely different. This observation puts the photo with the Doily-adorned person in another perspective. It is in fact a portrait of the artist, the artist who both unveils and masks himself.

1 Daniel Kruger, Between Nature and Artifice (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2014), 10.