Réka Fekete, A Dance of Light and Shadow, self-published, 2021.

Réka Fekete doesn’t have much time left. There is a time in our lives when things fall apart and we feel unable to control the slow collapse. It happens to all of us.

Réka doesn’t want to have a recurring cancer at age 39. She wants to keep making jewelry and living her life in Amsterdam with her husband. But she knows the end is coming soon, so with the help of some friends she decided to publish a monograph about her work to commemorate her love of art-making. Anything I say about the book pales in comparison to the circumstances under which it was made. Trying to put on a page images and words that sum up a life is an impossible task, but I will at least try to give you a summary of what the book looks like and what it says. These pages and words will help us remember Réka.

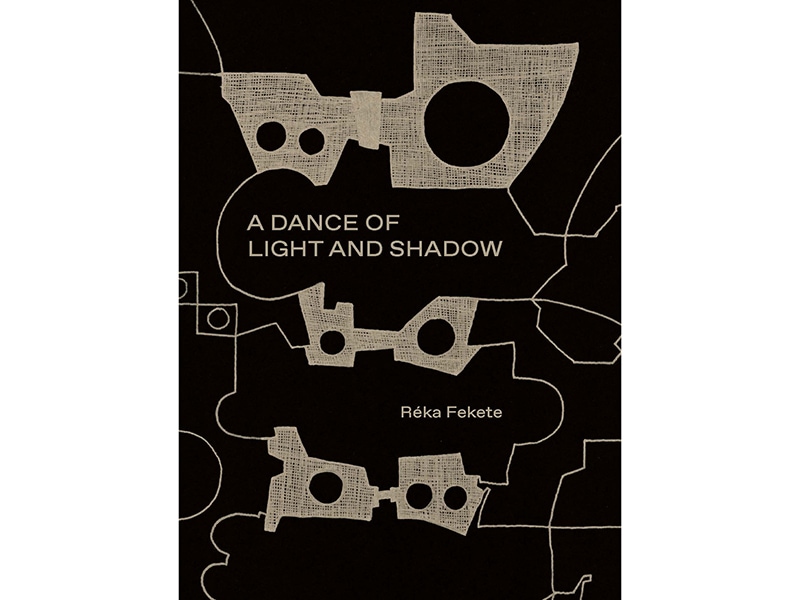

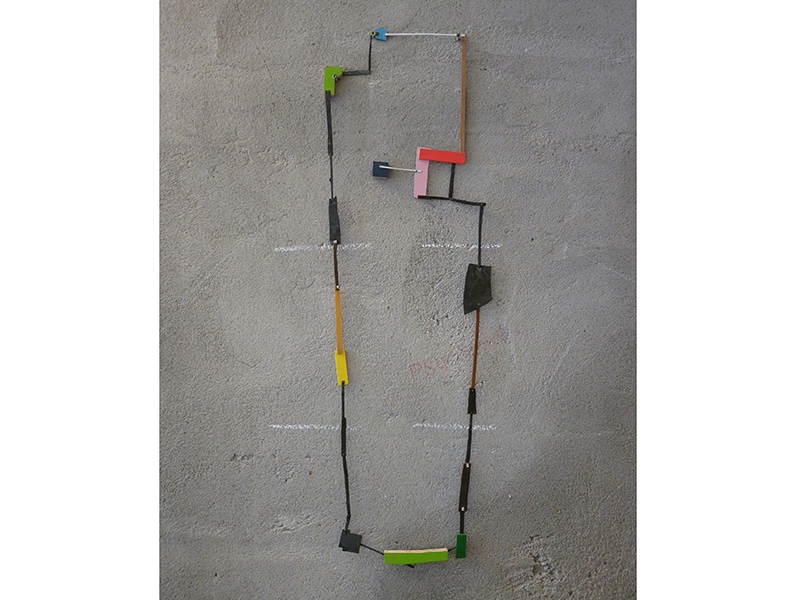

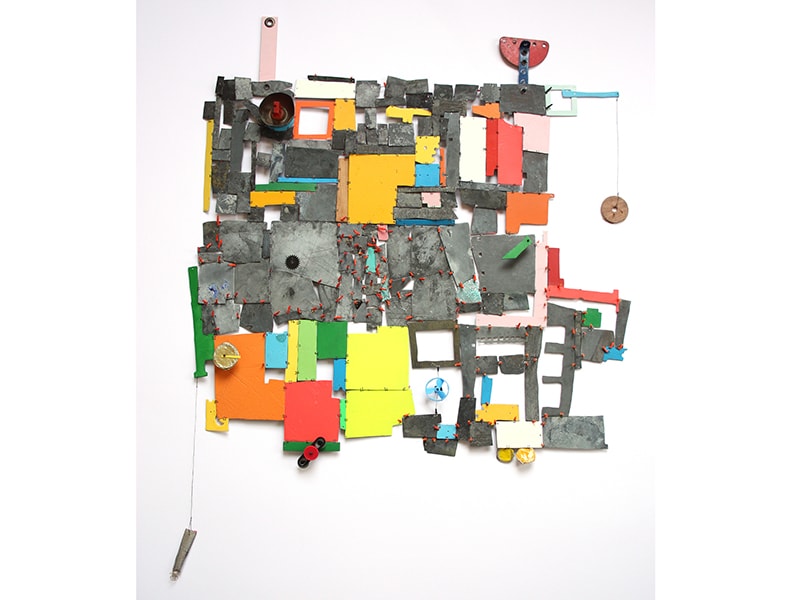

Physically the book feels like a hand-crafted art object. The letters of the title, A Dance of Light and Shadow, are the color of dull brown craft paper. They’re placed against a matte black background. Across the rest of the cover dance those imperfect, architectonic shapes Réka likes to use in her jewelry. They are textured building blocks with holes in the center, linked together by a line that wanders all over the front, the back, and into the large flaps of the soft cover.

But the most arresting aspect of the book is the shape. Not the frontal shape, which is the usual rectangle, but the side view. Put your hands together in the form of prayer. That is the shape of the book. It comes to a point on both sides, unlike other books that are squared off. It feels uniquely sensuous in the hand. Each page of text is printed on the same brown craft paper as used on the cover, with some images and drawings printed on glossy paper interspersed throughout, often with a colored filter over them.

There are two major texts, written in English, Dutch, and Hungarian, each in a separate chapter, along with a curriculum vitae and acknowledgements in the center of the book. The first text, called An Artist’s Life, is written by Ward Schrijver. In the second one, Between Unafraid and Uncertain, Through Life and Life’s Sorrows, Two Friends in Conversation, Liesbet Bussche interviews Réka.

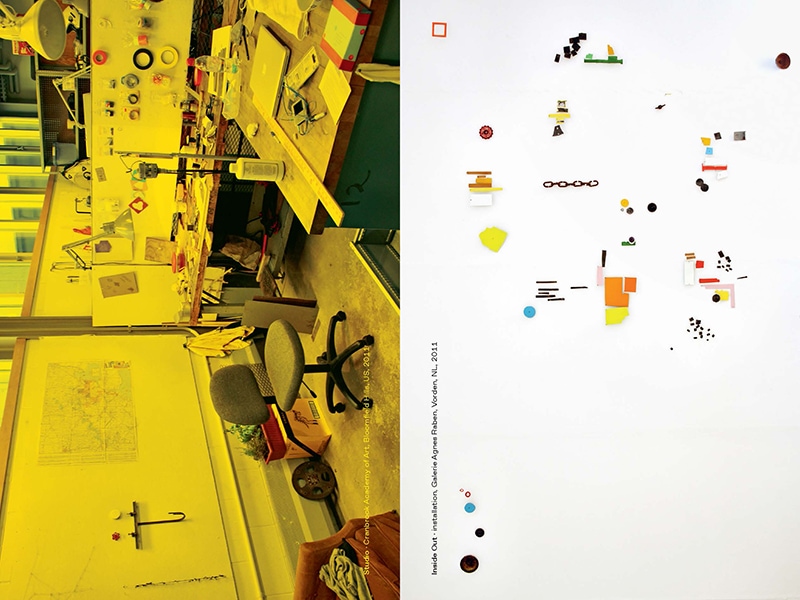

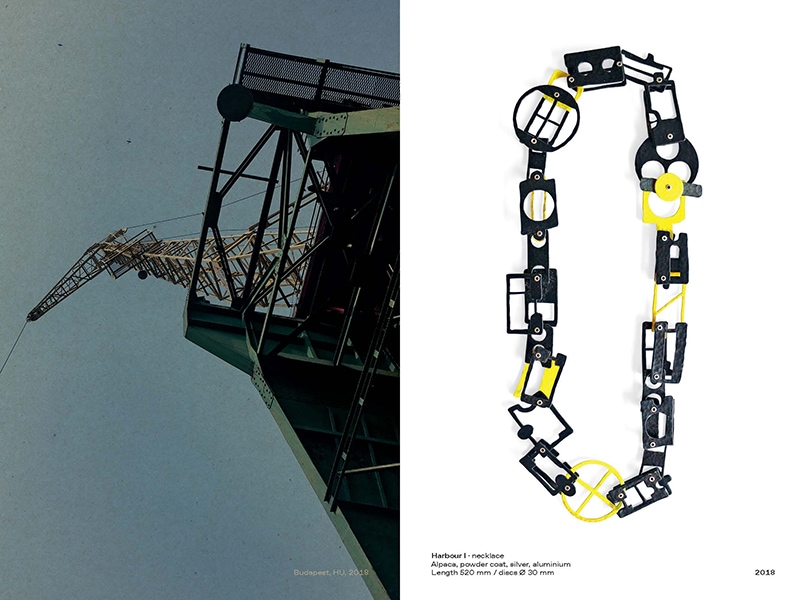

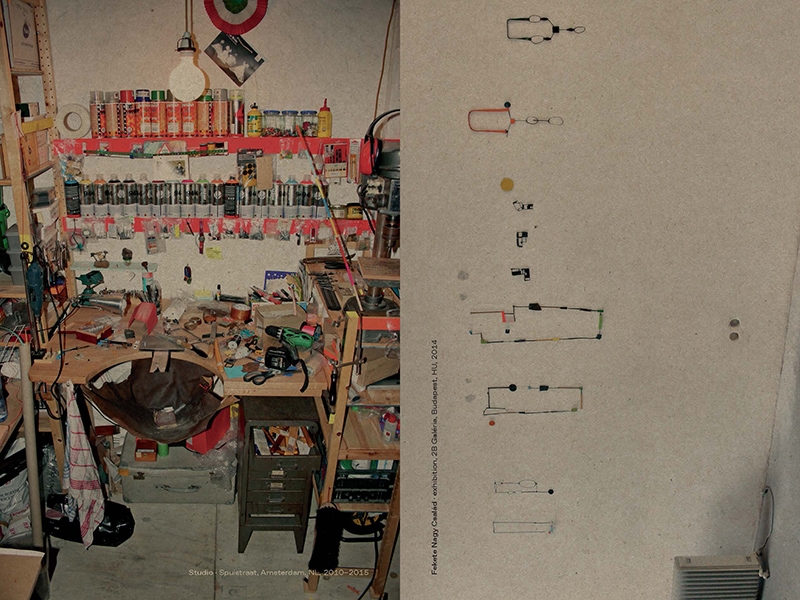

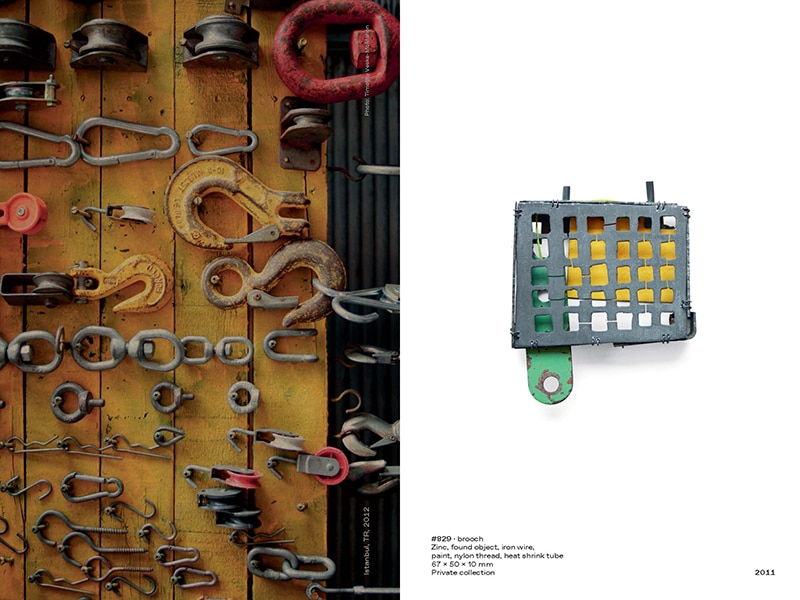

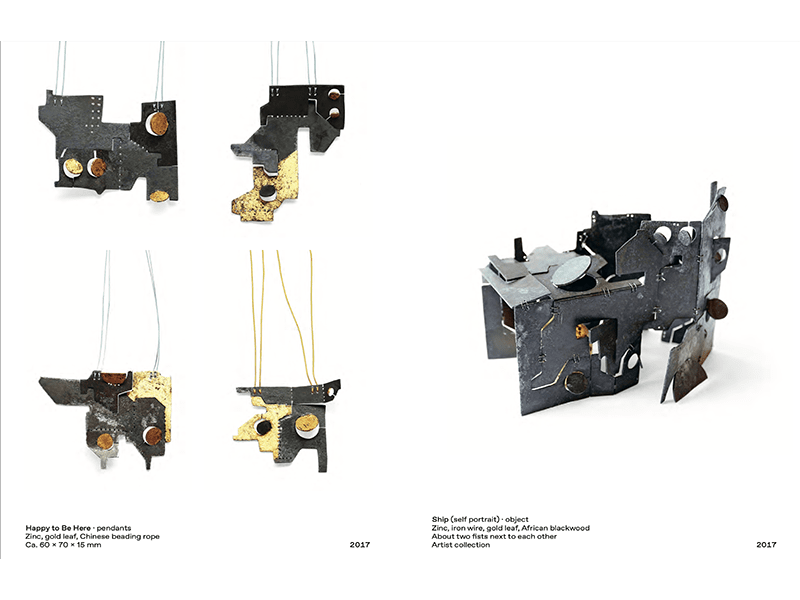

Between the chapters are images of her jewelry; close-ups and installation views along with single shots; work table arrangements; building facades; sketches; portraits of Réka; textures, tools, and materials; and curious points of view of pipes, wires, and landscapes. It is up to the reader to make connections between the inspirational images and the jewelry itself. Réka is giving us a key to the way she sees, and it is very effective. Her idiosyncratic view of the world appears as distinctly shaped pieces tentatively held together, resilient, and ready for change. There is a tender and fragile relationship between the singular objects.

In An Artist’s Life, Schrijver writes with the jewelry maker in mind. Starting the text with a description of Réka’s black logbook—in which she notes all the works she has made with a photograph, often with a drawing, dimensions, material list, and whether it sold—he describes drawings of her graduation pieces and then asks the question: Then what? He details the burst of post-graduate creativity, then the log goes blank as Réka’s life steers off course when she is first diagnosed with cancer in 2016. He observes, “this practically organized notebook suddenly becomes a document humain, a mirror of life.”

Then Schrijver asks another question: How does the creative process unfold for Réka? “In a sense, her inquisitive approach lingers in the work. There is always a flicker of restlessness left, and you constantly sense the temptation of the not-yet-fully-investigated. Purposely, no oval is ever completely regular, no square exactly square, no line taut and straight. … For her, the end result has to contain life.” This is an excellent description of Réka’s art and the way she works. She wants flexibility, nothing too predictable or boring.

Réka was born in 1982, in Budapest, Hungary, into a family of artists. Her grandmother makes jewelry. Her father taught her about renovating the Bauhaus building they lived in. She learned about making and tools from them. While Schrijver touches on these foundations, he doesn’t give a complete picture of the family or how they influenced Réka’s development.

Schrijver asks: “How does an artist choose a medium with which to express herself?” He talks about her training at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and how she experimented with several media and scales but then landed on the study of jewelry. However, she was never completely committed to its intimate scale and continued making wall hangings and standing objects. This lack of confinement grew more urgent when she learned about her cancer at age 33. Schrijver ends his text with a visit to see Réka at her house, and describes her energy and passion for continuing to work. Sketches and objects spread over all the tables, chairs, and floor of her home. He quotes her as saying, “I’ve never been so happy.”

Schrijver has given us a good but brief introduction to Réka and her artwork. However, we don’t know much about who she really is and what she believes. For example, he refers to a squat she lived in called Langgewagt, after which she named a necklace, but doesn’t frame the context of why she was living in a squat. Maybe there is an obvious reason, but should we have to guess? Another question that came up for me was which artists she respected. I really don’t get a sense of who she is in this text, only what she did.

Thankfully, there is the next section, in which her close friend and fellow jeweler Liesbet Bussche interviews Réka. Her first question is, “You were born in Budapest in 1982, the eldest of a family of four. Can you take me back to your childhood in Hungary?” Ah, so now we will get some personal background. Réka gives us a view into her youth, filled with artists and making things on her own. It sounds as if she didn’t have a large circle of friends until she moved to Amsterdam. Although she first wanted to be a social worker, she eventually decided to go to art school. Kind of by chance, she went to the Academie.

One thing neither text mentions are the teachers she most revered and learned from. In an interview I did with her for AJF in July 2013, she talks about how Iris Eichenberg, as her Rietveld professor, gave her a feeling for possibilities and permission to explore. She also interned with Beppe Kessler, where she observed the practices of a working artist, and that was hugely important for her as a student. (Kessler continues to be a close friend, and provided financial support to help Réka produce this book. And along the way Kessler and Bussche helped Réka make decisions and think about how the book should look and what it should contain.)

Another artist who she never met but learned a lot from was Onno Boekhoudt, whose work she catalogued for CODA Museum. She handled the work, and studied the notebooks and the experiments he performed. Boekhoudt had died a few years before, but she felt as if she were his student. It feels important to me to know about these influences. It tells me more about how Réka might have picked up her inclination for rectangular shapes from Boekhoudt or her love of experimentation from Eichenberg.

Her discussion of why she moved to the Netherlands is strikingly perceptive. She says, “Hungary’s hierarchical society and mentality didn’t suit me … And it was easier to rebel here than in Budapest. I loved having a kind of freedom that was lacking at home. I’m still Hungarian, but I also feel like a Dutchwoman. Or rather, as someone from Budapest and from Amsterdam. Amsterdam suits my personality better, how I want to be. I like how people live together here, how they are involved in society.”

Réka talks about how she uses her emotions to make her work and how the jewelry department made her feel like she was home or, as she says, in “a warm bath.” Much of her inspiration comes from buildings and perhaps from growing up in a Bauhaus-designed home. Many others have compared the training and images used in jewelry to architecture, but in Réka’s work you can really see the building blocks of shapes in her necklaces and brooches, as well as her wall hangings and sculptural forms. She sees her jewelry as an object and is not much concerned with the body. Besides, she considers herself a maker of many things and feels that the world of jewelry is too “mannered, too polite … the jewelry world sometimes feels too oppressive.”

The interview with Bussche has added a lot to our understanding and knowledge of the artist. Réka declares that now that she doesn’t have much time left to live, she wants to continue making from an inner need, without worrying about where she stands in the field of jewelry. In other words, making without judgment, for the sheer joy of it. It doesn’t matter what others think or if anyone wants to buy it—it’s a wise and insightful concept to be seriously considered by us all.

Does the book provide us with a full picture of Réka and her artwork? That is a hard question to answer. But A Dance of Light and Shadow shares how Réka thinks about jewelry and life. It is a valuable addition to the literature about the contemporary jewelry field with its in-depth reflection on the life and work of one jeweler. It is a beautiful and heartfelt tribute to a creative and openhearted person. Réka’s work is unique and worth spending time with, and that can’t be said of everyone. I, for one, was happy to spend some time getting to know Réka through this publication.