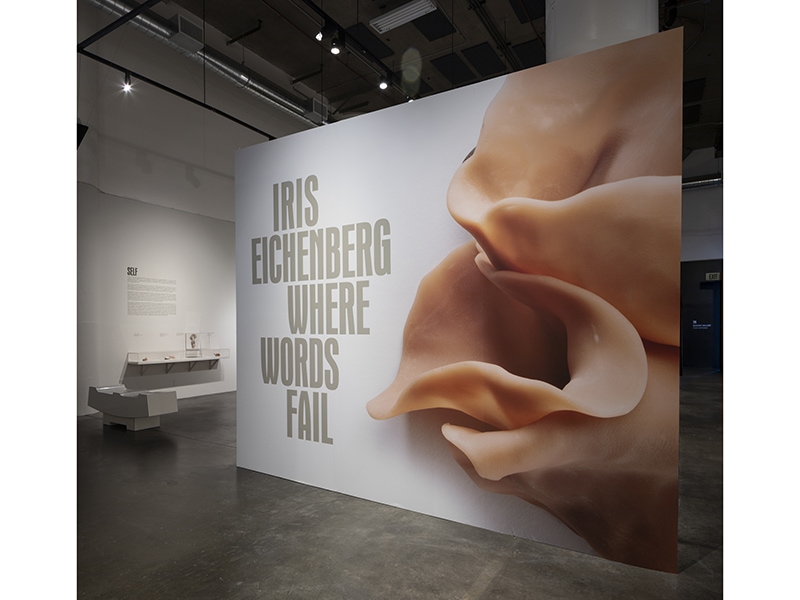

Iris Eichenberg: Where Words Fail

June 25–October 30, 2022

Museum of Craft and Design, San Francisco, CA, US

“That we find a crystal or a poppy beautiful means that we are less alone, that we are more deeply inserted into existence than the course of a single life would lead us to believe.” —John Berger

In Iris Eichenberg’s mid-career survey, the selection of works by curator Davira S. Taragin, and the exhibition design by John Randolph make us feel that we are less alone.

This exhibition shows 40 of Eichenberg’s works presented with a logic that is neither chronological nor formal. Objects, jewelry, and installations compose different landscapes as if they made up a person’s geography—the material landscape of the first half of the artist’s life.

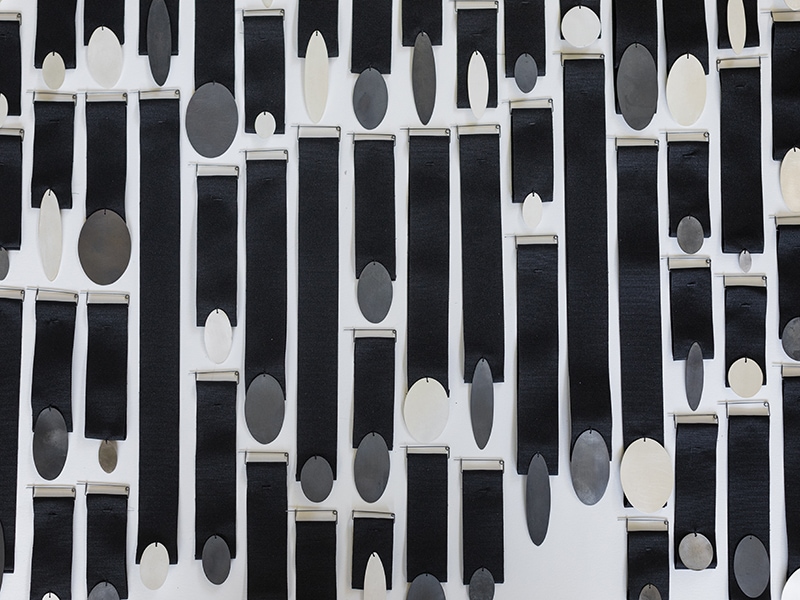

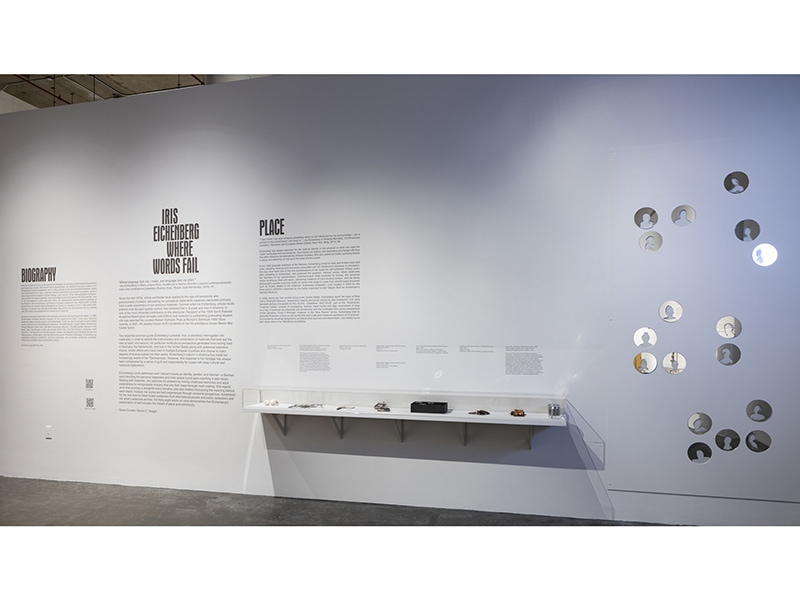

With a strong presence throughout the entire exhibition, Taragin’s curatorship shows a clear, well-defined selection of works that build up a narrative. Before we enter the main room, there is a small space, a hall where we are welcomed by a series of pieces made between 2004 and 2008. They are a selection of objects and brooches made of leather, gold, fabric, bone, paper, vintage buttons … family treasures that fit in the palm of your hand. Apprehensible in every sense, they can be read as a system of references to understand the topography we are about to see. This first showcase displays an artist’s material universe. It gives the audience an insight into contemporary jewelry and presents Eichenberg as a key player in the field.

This first showcase is followed by an installation of circular mirrors fit into the wall and etched with portrait sketches. We are reflected on those minimal lines. There, we can become aware of others, like an invitation to view the exhibition while searching for ourselves in every piece we see. Then, before immersing ourselves in the exhibition, we can watch a video—another device Eichenberg uses confidently. In it, a landscape moves slowly without becoming distorted, demanding our close attention so we can understand it and grasp even the slightest movement.

The whole exhibition is summarized in what we find at this first moment. Curatorship, assembly, and lighting are put together in balance. This allows us to comfortably enter the space created by the artist through the clearness of each of her artworks.

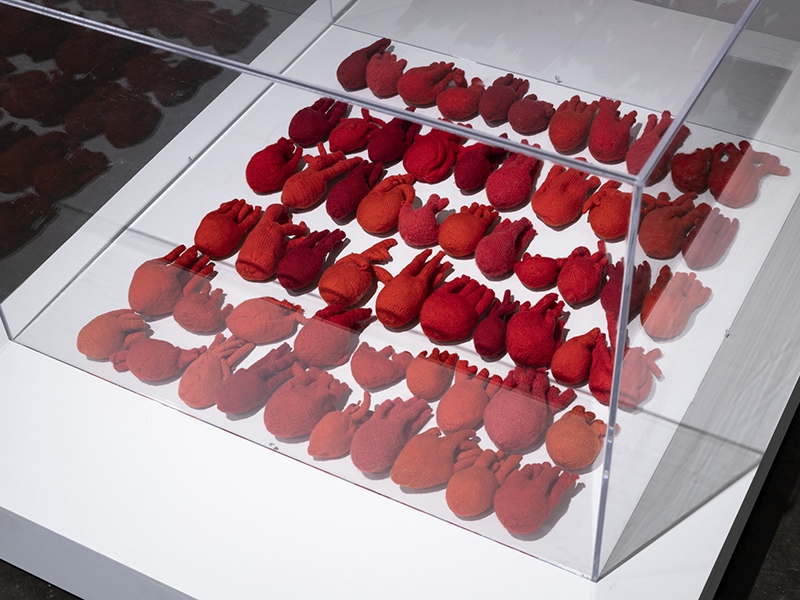

A very large bird and an ex-voto in the shape of an arm hang from the wall. Below are hearts knitted from red wool, followed by around 50 medals. Another ex-voto, of a hand, rests against the wall. A showcase preserves, as if a relic, a half-opened travel altar holding golden wedding rings and two slices of some kind of horn. And so the exhibition includes everything from artworks that clearly convey portability and use to pieces that are unconnected with the classical uses of jewelry yet somehow relate to the body and appeal to it.

The pieces are foreign to this space. They are aliens occupying a new habitat with a kind of uneasiness. This status of Eichenberg’s pieces puts the viewer and the artworks on a par. There are no hierarchies of knowledge. The artist does not seek to place herself above her audience. It is as if her art invites us to pay careful attention to what surrounds us so together we can find a new way to understand the world. The exhibition’s diverse materialities imply diverse possibilities, different answers to some question that are connected with the yearning for being certain that we are part of something, that we are less alone.

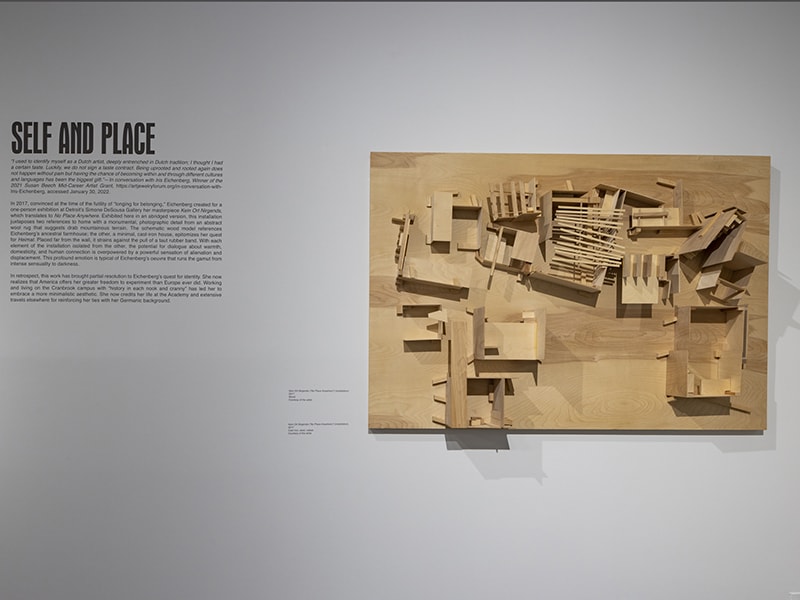

One of the pieces from the 2017 series Kein Ort Nirgends (No Place Anywhere) is dramatically set in the middle of the room: a small cast iron house lassoed by, and testing the tension of, a rubber band secured to the wall. On the wall we can see a photograph. It is the detail of a rug made by the artist to resemble the air landscapes of the fields in Germany, her home country. On the other side of the band hangs a wooden model of the family farm where she grew up.

In his Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard says that our house is our first universe:

“We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost. Thus, by approaching the house images with care not to break up the solidarity of memory and imagination, we may hope to make others feel all the psychological elasticity of an image that moves us at an unimaginable depth. Through poems, perhaps more than through recollections, we touch the ultimate poetic depth of the space of the house.”

This series of works collected at the horizon line—the artist’s prime geography—has an identity of its own while permeating the rest of the works regardless of when they were made. The selection of materials is the result of a poetic search rather than a demonstration of virtuosity.

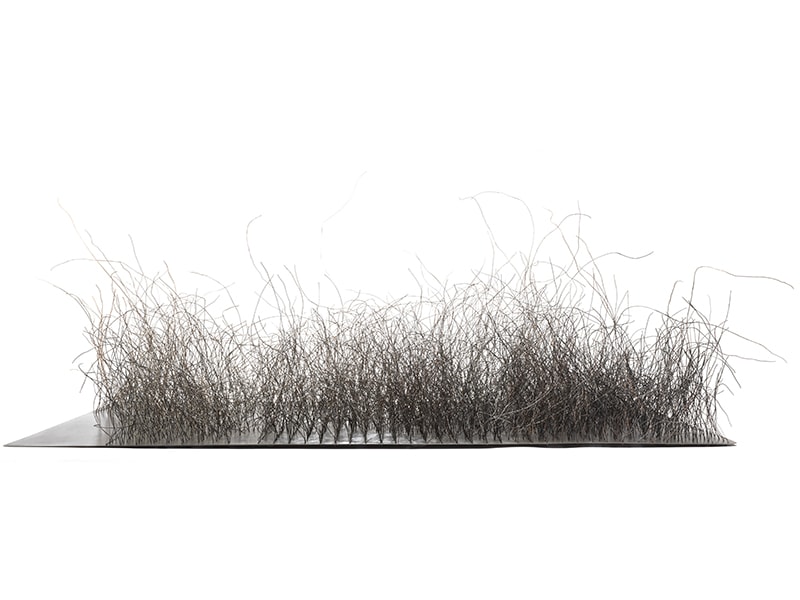

In the middle of the room we find a different landscape: Field (2022), a rug made of steel and brass wire.

“We are torn between nostalgia for the familiar and an urge for the foreign and strange. As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.” —Carson McCullers

Because this is a mid-career retrospective, this piece gives us clues to the new conversations Eichenberg might propose to us through her next works. The new sceneries may still be unknown to her but they will undoubtedly cast the same energy as her existing pieces.

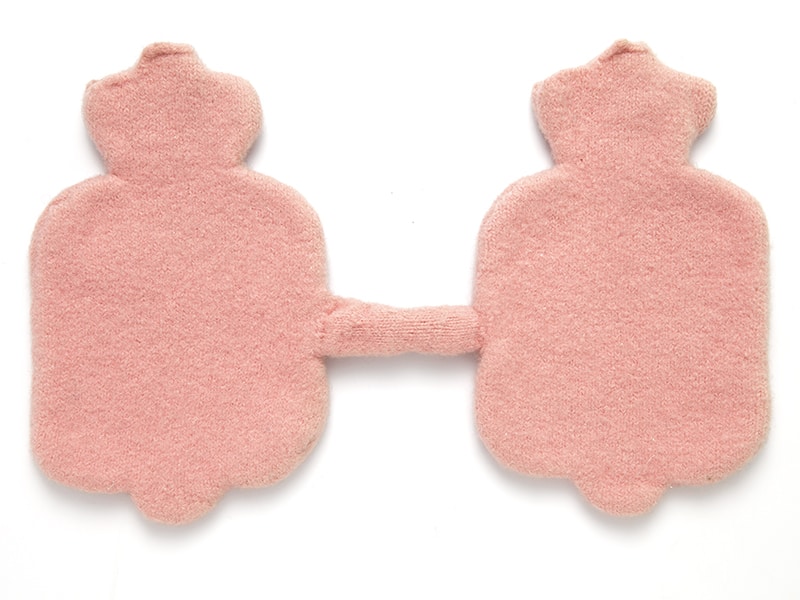

It is not possible to speak about Eichenberg’s work, and especially about the oeuvre in this exhibition, without referring once and again to materiality. But it is important to relate the term with the religious realm, particularly with ex-votos, a typology used by the artist. Ex-votos are material testimonies of faith, proofs of the efficacy of a devotional act. When words fail, Eichenberg resorts to materials. By knitting, embroidering, repeating an obsessive gesture upon a surface, she creates her own devotional act.

Devotion to her work and her creative process redeem her. These pieces are a testimony to the fact that art is a way of saving ourselves.

Note: Iris Eichenberg: Where Words Fail was made possible, in part, by the Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant, which Eichenberg won in 2021.

The exhibition was accompanied by a publication and an audio description. Visit the Museum of Craft and Design’s exhibition page here.

LA POÉTICA DE LA MATERIA

EL PAISAJE MATERIAL DE IRIS EICHENBERG

Iris Eichenberg: Where Words Fail

Junho 25–Outubro 30, 2022

Museum of Craft and Design, San Francisco, USA

“That we find a crystal or a poppy beautiful means that we are less alone, that we are more deeply inserted into existence than the course of a single life would lead us to believe.” —John Berger

En esta exposición de mitad de carrera de Iris Eichenberg, tanto la selección de obras, hecha por la curadora Davira S.Taragin, como el diseño de montaje de John Randolph, y la obra de la artista hacen que al entrar en la sala del Museo de Craft and Design de San Francisco nos sintamos menos solos.

La exposición reúne alrededor de cuarenta obras agrupadas con una lógica que no es cronológica ni formal: objetos, joyas, instalaciones conforman diferentes paisajes como si de la geografía de una persona se tratara; el paisaje material de la primera mitad de la vida de una artista.

La curaduría tiene fuerte presencia a lo largo de todo el recorrido de la exposición; es notable el trabajo de selección para la construcción de un relato. Hay un pequeño espacio antes de entrar de lleno en la sala principal, un hall donde nos reciben una serie de piezas hechas entre 2004 y 2008, una selección de objetos y broches de cuero, oro, textiles, hueso, papel, botones antiguos, tesoros familiares que caben en la palma de la mano, son abarcables en todo sentido y pueden leerse como sistema de referencias para entender la topografía que veremos a continuación.

Esta primera vitrina presenta el universo material de una artista y también opera para entender de qué se trata la joyería contemporánea y porqué Iris Eichenberg es un referente en este campo.

A esta primera vitrina le sigue una instalación hecha de espejos circulares encajados en la pared y grabados con bocetos de retratos, nos vemos reflejados en esas mínimas líneas en las que podemos descubrir a otros, como una primera invitación a mirar la exposición buscándonos en lo que vamos a ver. Y antes de estar de lleno en la muestra tenemos un video, recurso que tampoco le es ajeno a Eichenberg, una pantalla muestra un paisaje que se va moviendo lentamente sin llegar a distorsionarse y que nos incluye pidiéndonos mucha atención para poder entenderlo y percibir el mínimo movimiento.

Toda la exposición está resumida en lo que encontramos en este primer momento. Curaduría, montaje e iluminación trabajan armónicamente para que podamos entrar cómodamente en el espacio que, con la claridad de cada una de sus piezas, genera la artista.

Un pájaro muy grande y un exvoto con forma de brazo cuelgan de la pared; debajo, corazones rojos tejidos en lana seguidos por unas cincuenta medallas. Otro exvoto de una mano se apoya en la pared, una vitrina preserva, como si de una reliquia se tratara, un altar de viaje a medio abrir donde se ven alianzas de casamiento doradas, y dos rodajas de algún tipo de cuerno… La exposición continúa así entre obras en las que claramente se pueden entender la portabilidad y el uso, hasta piezas que no responden a usos clásicos de la joyería pero que de alguna manera se relacionan con el cuerpo y lo interpelan.

Las obras son claramente ajenas a ese espacio, son extranjeras ocupando un nuevo hábitat con cierta incomodidad. Esta manera de estar de las piezas de Eichenberg hacen que el espectador y la obra se encuentren en la misma posición; no hay jerarquía de conocimientos ni un deseo de la autora por ponerse por encima de su público; es como si la obra nos invitara a prestar mucha atención a lo que nos rodea para encontrar juntos una nueva manera de entender el mundo. Las diferentes materialidades de las obras son diferentes posibilidades, diferentes respuestas a alguna pregunta que diría, aunque no pueda estar segura, tiene que ver con la necesidad de pertenencia, con el anhelo de certeza de saber que somos parte de algo.

wood, 115.6 x 167.6 x 27.9 cm, photo: Tim Thayer

Una de las piezas de la serie Kein Ort Nirgends (Ningun lugar en ningún lado) de 2017 irrumpe en medio de la sala: una pequeña casa de hierro fundido que sostiene en tensión una banda elástica amurada a la pared donde vemos la foto de un detalle de una alfombra hecha por la artista dibujando el paisaje aéreo de los campos de Alemania, su lugar de origen y del otro lado una maqueta de madera de la granja familiar donde creció. Dice Gaston Bachelard en “La poética del espacio” que la casa es nuestro primer universo

Nos reconfortamos reviviendo recuerdos de protección. Algo cerrado debe guardar los recuerdos dejándoles sus valores de imágenes. Los recuerdos del mundo exterior no tendrán nunca la misma tonalidad que los recuerdos de la casa. Evocando los recuerdos de la casa, sumamos valores de sueño; no somos nunca verdaderos historiadores, somos siempre un poco poetas y nuestra emoción tal vez sólo traduzca la poesía perdida. Así, abordando las imágenes de la casa con la preocupación de no quebrar la solidaridad de la memoria y de la imaginación, podemos esperar hacer sentir toda la elasticidad psicológica de una imagen que nos conmueve con una profundidad insospechada. En los poemas, tal vez más que en los recuerdos, llegamos al fondo poético del espacio de la casa.

Este grupo de obras reunidas en la línea de horizonte, la geografía primaria de la artista, tiene una identidad en sí mismo pero impregna el resto de las obras independientemente de cuando hayan sido hechas porque señala cómo la selección de las materialidades responde a una búsqueda poética y no a una muestra de virtuosismo.

En medio de la sala nos encontramos con una paisaje diferente, Field, una alfombra de acero y alambre de bronce, obra de 2022.

“We are torn between nostalgia for the familiar and an urge for the foreign and strange. As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.” —Carson McCullers

Por ser una retrospectiva de mitad de carrera, esta pieza y lo que dice Carson McCullers nos dan pistas de lo que vendrá, de las nuevas conversaciones que Eichenberg puede proponernos con sus próximos trabajos, los nuevos escenarios quizás desconocidos para ella pero que vislumbran la misma energía de sus trabajos de siempre.

Es imposible hablar del trabajo de Iris Eichenberg, y en particular del cuerpo de obra de esta exposición, sin hacer referencia una y otra vez a la materialidad, pero sería importante relacionar este término con lo religioso en particular con los exvotos, tipología usada por la artista. Los exvotos son testimonios materiales de fe, son pruebas de la eficacia de un acto devocional. En la muestra “Cuando las palabras fallan” (When words fail) Iris Eichenberg recurre al material y tejiendo, bordando, repitiendo un gesto obsesivo sobre una superficie, crea su propio acto de fe.

La devoción por su trabajo y su proceso creativo la redimen. Estas piezas son un testimonio de que el arte es una manera de salvarnos.

Nota: Iris Eichenberg: Where Words Fail fue posible, en parte, gracias a Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant, que Eichenberg ganó en 2021.