August 2–September 22, 2019

108|Contemporary, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA

Take a moment to close your eyes and imagine a construction site. You might see people wandering, people working, equipment, dirt, or dust kicked into the air. The site looks disorganized, but you might imagine there’s a reason for the disarray of tools and supplies; it could be a build in progress or perhaps a demolition underway. Now take away the debris and dust, pack away the equipment and any sign of disorganization. Replace it with jewelry, clean surfaces, and a rhythmic beat. Construction hats, scaffolding, I-beams, caution-tape yellow, concrete surfaces, and shards—and a mass collection of jewelry. As a visitor to 108|Contemporary in Tulsa, OK, USA, you’ll be confronted with all of these things while viewing curator Erin Rappleye’s exhibition, Building on the Body: Identity, Materials, Jewelry.

Erin Rappleye is assistant professor of art at Tulsa Community College. She gathered the work of 15 artists from across the globe working in materials that are used in or associated with the industrial landscape. These artists draw from observations and memories, exposing parts of their identity and personal associations through the format of jewelry. The exhibition contains pieces made with an array of materials and approaches that express ideas of space and constructed environments. I foresee that Erin’s success with Building on the Body: Identity, Materials, Jewelry will initiate more jewelry exhibitions throughout Oklahoma.

When I first heard the title of Erin’s exhibition, I questioned how she might reference or use the body within the gallery. The title Building on the Body caught my attention because we artists who primarily work in a jewelry format are always hunting for authentic ways to display jewelry in a space but also have concerns with representing the work as it ought to be seen—on the body or at least in a way that suggests wearability. To those unaware of the jewelry field, the large necklaces, brooches, and bracelets in Building on the Body might seem outlandish or beyond the capability of daily wear; however, let us all be reminded, it is jewelry and it is meant to be worn, regardless of scale or material.

I spoke with Jack Dean, communications coordinator of 108|Contemporary, about the installation during my visit. Jack shed some light on the choices that were made concerning the audience, and how to prove these works are wearable. As you enter the space, your view of the exhibition is partially blocked by a large yellow scaffolding with a semitransparent fabric filling its void. On the fabric are faint projections of people wearing pieces from the exhibition. Not only do they wear these large-scale pieces, but they act as if the jewelry isn’t even there.

Each person in the projection seems to engage in a daily activity, such as drinking coffee or listening to music; as one person fades, another begins to overlap their presence and they seem to exist in the space together, all wearing bold architectural and industrial-inspired jewels. This active projection of wearability presented humor, a scale for the work, and showed how the chosen pieces articulate to the human form. The combination of a see-through fabric and faint projection was captivating, forcing me to stand there for some time in order to focus and determine what I was seeing.

The display carries the viewer through the exhibition in a nonlinear path. Giant I-beams lay over one another covered in jewelry. I immediately personified the I-beams, imagining them as people lounging, or envisioned the jewelry on them as people, resting casually as if they were on a job-site taking their lunch break. These large, horizontal, nontraditional plinths divide the gallery into segments; the gentle incline of the topmost beams carries the viewer across the gallery. I immediately followed these inclines, which led me to the work on the perimeter walls. As I wandered through the space, I would discover another one of the 15 artists, and it sparked a treasure hunt for me to find their other work in the gallery. Throughout the gallery and accompanying the work, wall plaques shared personal statements or insights into each artist’s philosophy. This extra insight had me bouncing through the space, searching for connections between artists, materials, and compositions.

The layout is clever and clean, and the variety of work is well distributed throughout the gallery. Erin used caution-tape-yellow paint and concrete shards throughout the space, incorporating them into the display and creating accents on the walls. Large horizontal stripes climb up the gallery wall, mimicking a Donald Judd installation but also reminiscent of architectural barriers; the large stripes mirror the scale of the scaffolding near the entry. These additional elements emphasize the height of the space; the eye follows the yellow paint toward the ceiling, bringing awareness to the architectural space of the gallery. Leading the viewer to pay attention to the surfaces and structures that often go unnoticed exemplifies the mission of the show.

Building on the Body: Identity, Materials, Jewelry explores how we as a society identify with architectural and built spaces. It questions how these common surroundings play an active or sometimes inactive role in our daily lives and interrogates the role of precious materials. In the show, there’s a range of materials used with a variety of approaches as these artists reexamine spaces which are typically used for shelter and protection. Some pieces have a stronger connection to the theme, with more direct use of materials, but I completed the gap for those works I felt to be less immediately discernible, inventing my own sub-categories for the work, which are as follows: “Commuter’s Landscape,” “Industrial Supply,” and “Rhythmic Space.” Although I’ve grouped works together as follows, many artists could be placed in more than one.

My “Commuter’s Landscape” group comprises artists whose work is observation-based, and often uses materials or compositions you’d find in the façade or framework of a structure. The intricate brickwork in Sharon Massey’s work reverses our experience with architecture, the wearer now adorned with miniatures of what we typically see as monolithic structures. The delicacy and scale of her brickwork elevates the ideas of labor, creating a connection and appreciation of the industrial landscape. Her use of geometric and jewelry-related forms builds precious moments, creating souvenirs of an urban landscape. The creation of tiny masonry work and galvanized steel creates complete compositions, referencing both interior and exterior surfaces.

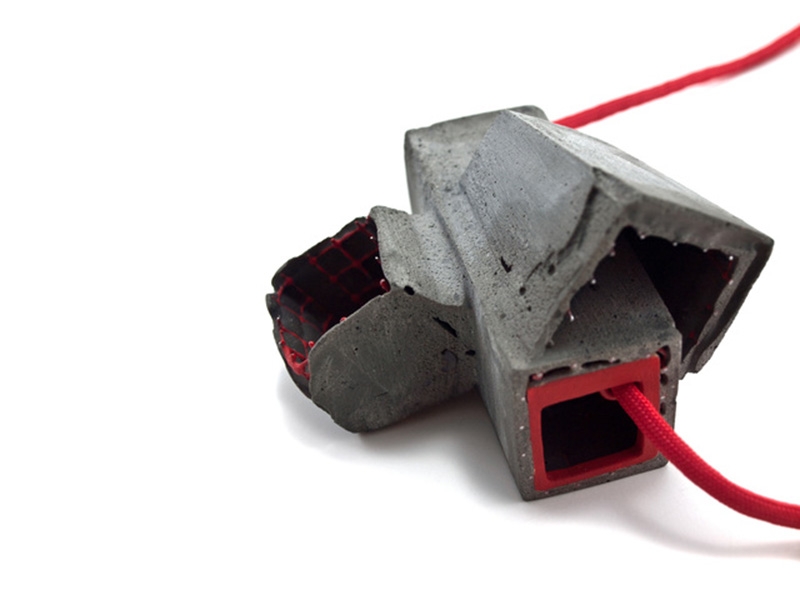

The geometric cast concrete jewelry by Demitra Thomloudis is highlighted with color-block surfaces of both bold and pastel hues. Similar to Massey, her work examines the value of site-specific locations and feels like an extraction of fragments from an existing place. Thomloudis captures delicate and often unseen moments of construction and deconstruction; her sensitivity to material use and composition is both captivating and soothing. The incomplete concrete surfaces expose reinforcements of gridded steel, granting the viewer personal access to interior spaces. Her neckpieces articulate around the human form with the use of hinges and fibers, allowing wearers an intimate contact with materials and structures they often experience in vast scale. Using these materials and forms in a jewelry format brings significance and attention to the commuter’s landscape, allowing viewers to identify and reflect on their relationships with the built environment.

The color palette in Kat Cole’s work is hard to miss; her use of warm tones with slight pops of cooler tones is striking. It lures me in every time, as I desire to find these colors within my immediate day-to-day surroundings. Cole’s puzzle-like, bold-colored enameled necklaces morph together zoning maps and aerial landscape views. These works create a state of relocation, as if someone is traveling by air and looking down on the miniaturized world, like the segmented crop lands of the Midwest. Her solid and pierced fabricated forms are placed together harmoniously in tight compositions comparable to crowded or sprawling metropolitan areas.

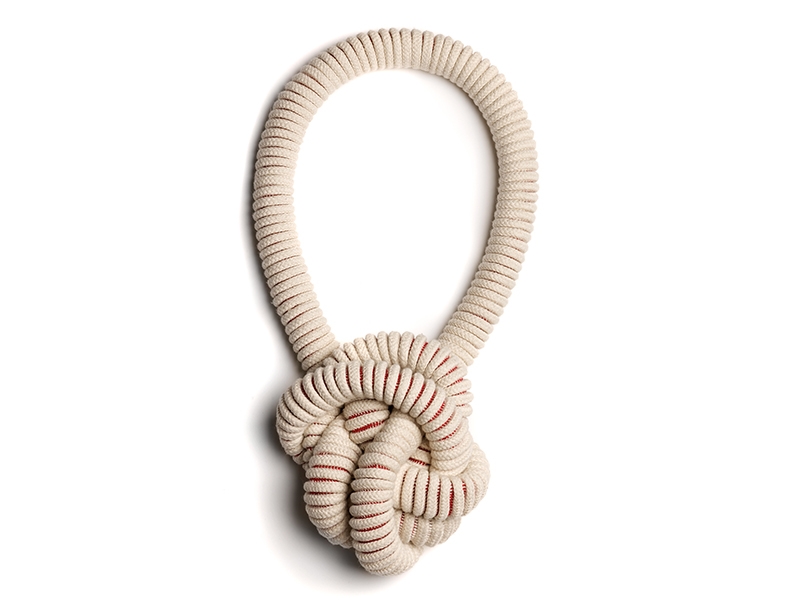

The artists who fall into my category of “Industrial Supply” limit their palette with manufactured materials, focusing more on recognizable jewelry forms. By concentrating on one material and using it meticulously, these artists build structures and forms that might relate to man-made spaces. The work in this category was more challenging for me to place within the overall theme, but with time I recognized its ability to bridge the gap through direct material use and suggestive forms, and represent what might be a product of industrial spaces. London artist Eleanor Bolton’s primary materials are cotton, rope, and yarn. Her massive cotton necklace imitates flexible aluminum ductwork. Ritsuko Ogura layers corrugated cardboard perhaps hundreds of times to build voluminous jewelry forms. Within each small opening in the corrugation, you might see color transforming this often-discarded material into something wearable. Yong Joo Kim uses Velcro fasteners to build layers, creating bracelets and necklaces. These works relate to aspects of experiential architecture as they suggest transformation of the expected into something unseen.

You always find a rhythm within architectural structures; think of stairwells, windows, railing, breezeblocks, or even mosaics. You will inevitably find a pattern. The artists in this group use repetition as a visual language and also as fuel to their practice. Jess Tolbert satisfies aspects from both the material focus of “Industrial Supply” and the repetitions of the “Rhythmic Spaces” group. Tolbert’s use of staples is noteworthy. Her interest lies in the staple’s functional component and its nature as a generally overlooked item. Reflecting on labor and mass production, she fits in with the artists I’ve mentioned above. The use of rhythm, layers, and repetition are suggestive of built environments. In this work and the context of Building on the Body, I see reference to identity, homage to specific place, and tiny skyscrapers with rhythmic facades. These highly structural hollow forms remind us of the hand. It’s in our nature to let architecture and industry become overlooked; the labor and the human role behind the work often remains forgotten. But Tolbert’s work requires a unique level of precision and attention, and serves to remind us of the simplicity of things forgotten.

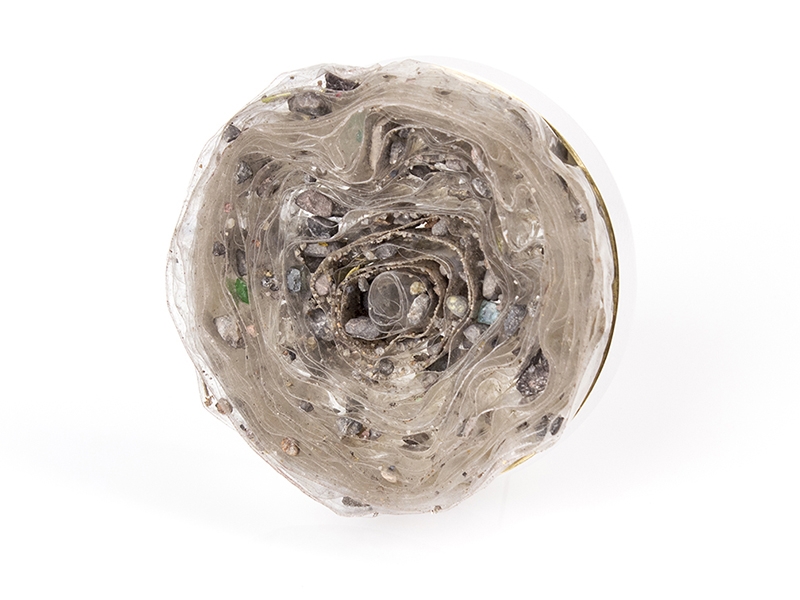

Motoko Furuhashi’s work falls into all three of the subcategories I invented. Her approach is inspired by personal association with place, limited material use, repetition, and pattern in both appearance and practice. Patterns and rhythms are like a cycle beginning and ending essentially at the same point. In her work, Furuhashi literally collects debris as she walks from point A to point B; the brooches are primarily made from clear tape that she unrolls and walks over, collecting fragments from the ground. These pieces may not directly feature specific building structures and architectural forms, but in their entirety they suggest a cycle of beginning and ending, the cyclical nature of human passage and impact on environment, and elevate places and materials that are so often overlooked. The onion-like layers of tape are filled with bits of dirt, sticks, and colorful debris, capturing a new identity for Furuhashi’s chosen collection sites.

I appreciate Building on the Body for its broad range of techniques, materials, and how Rappleye left space within her selection of artists for the viewer to make connections to the theme. It’s refreshing to see some overlap between artists’ thoughts and common spaces between their perceptions. Sharing experiences and awareness keeps us humble. We so often take for granted the structures that give shelter, harbor creativity, house our loved ones, and create modern spaces around us by interrupting the natural landscape. Presenting these notable forms on the body as jewelry highlights an appreciation for and connection to the built environment as something that is and should be viewed as precious.

I hope this exhibition educates those unaware that jewelry has the capacity to insert itself within society, fueling dialogue and providing room for reflection and understanding amongst one another. When worn, these pieces have the ability to transform the body into part of a landscape, whether suggestive or real. The work in Building on the Body shifts the scale and perspective on how we view the architectural language that surrounds daily life.