Ground: A Retrospective Exhibition of Ruudt Peters

Ground: A Retrospective Exhibition of Ruudt PetersMay 22–July 31, 2015

Massachusetts College of Art and Design, President’s Gallery, Boston, USA

Born in 1950 in in the Netherlands, Ruudt Peters is lauded as a prominent and provocative figure in the contemporary jewelry world. He tends to translate big ideas into beautifully crafted jewelry and, through his exhibition design, creates challenging experiences for his viewership. As a conceptual jeweler, Peters investigates ideas through the creation of series of work in various materials, works that explore concepts such as the micro and macro, change, the body, time and continuity, male and female energy, and religion. Individual pieces investigate a facet of these concepts, and are cohesively brought together through a specific narrative. He organizes and displays the resulting series using the exhibition as a point of transition before the work leaves the gallery and goes into a private or public collection.

Ground extends Peters’s track record of creating bold jewelry displays in relation to the exhibition space. The exhibition at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, organized by Heather White van Stolk, is a visual autobiography of Peters’s work beginning in the 1970s. Installed in the President’s Gallery, the vestibule to the president’s office, the exhibition expands from an entranceway into a larger space that connects various administrative offices.

Peters gave the keynote speech at the Society of North American Goldsmiths conference “Looking Back, Forging Forward” on May 21, in which he presented images of his work and inspiration in rapid succession, relaying to the audience just how quickly his mind moves and the many connections he makes through exploration and travel. This exhibition, organized in conjunction with the conference, parallels his ideas as each vitrine represents jewelry series he has created in the past: Passio, Iosis, Lapis, Oroboros, Lingam, and Qi, to name a few.

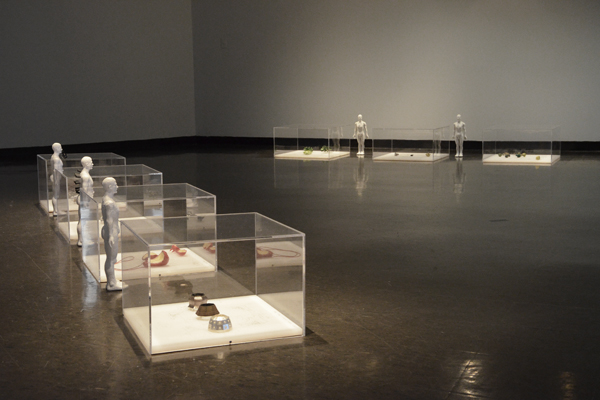

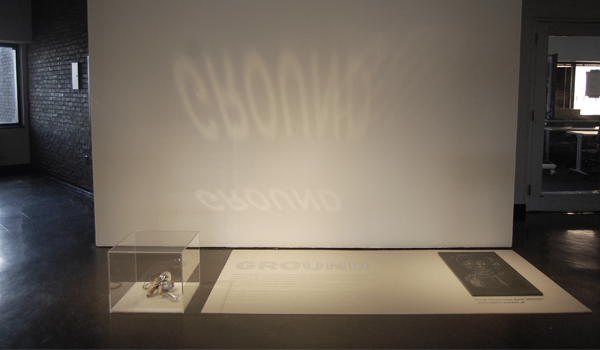

As viewers enter the gallery, they confront the exhibition title, introduction text, and first vitrine on the ground before them. Following the sequence of vitrines installed directly on the gallery’s floor, one can see the various thematic concepts that Peters has explored over the course of his career. Each case’s surface features his blind drawings of the human form, quick dynamic sketches that Peters made with his eyes closed, rendered on Plexiglas with jewelry placed upon them. Other than a short introduction, there are no formal labels in the exhibition. The titles and dates of the pieces are handwritten on the Plexiglas below each work, and viewers are left to look at each object and form their own interpretations.

The drawings provide a visual bridge teeming with energy and connecting the jewelry with the earth. They also unify the visually diverse series, created over 40 years in a variety of materials and techniques. As most of the drawings are of the human form, they give us a sense of placement and the relationship of jewelry and the body.

The title panel directs visitors to access a YouTube link of Peters expounding on Ground. In the video, Peters explains using the concept of “ground” to connect himself to the earth’s energy. The video is a helpful key to Peters’s work. As he has made clear through writings and various presentations, Peters identifies the ground as a gateway, and asks his viewers to be aware of their own bodies and energies interacting with the jewelry as it is set out on the floor. Throughout the exhibition we see small male figures rendered in porcelain. These little figures stand beside the vitrines, giving the viewer another object to explore—and like the low vitrines, they require us to kneel down to examine the meridian points mapped on their bodies. Each man has a different part of his body modified—one has glazed feet; another has a bubble coming out of his mouth; a third, little pins along the spine at the chakra points; and a fourth, the Kabbalah’s Tree of Life’s nodes marked with cones.

The Plexiglas cases are almost like coffins, and the porcelain effigies contribute to the feeling of walking into a quiet crypt. However, once we do make that pilgrimage to the eleventh-floor gallery, we are rewarded with an intriguing exhibition of masterfully created jewelry. Since the jewelry is covered, our only opportunity to “touch” the work is not with our hands but with our bodies as we kneel on the ground. The ground, then, becomes a conductor between our body and the work, which is only accessible when we physically and deliberately move close to the objects. This is in line with Peters’s exhibition history, which requires his visitors to perform certain actions and position themselves in certain ways in order to interact with the work. Genuflection is meditative, and encourages us to contemplate the pieces presented with the attention and at the speed usually reserved for devotion or spiritual exercises. In grounding ourselves before each vitrine, we are anchored before it and encouraged to think through each piece and series.

The unconventional installation is engaging, yet it does diminish the accessibility to the jewelry itself. Those visitors not able or willing to lower themselves to the ground will miss the exhibition almost completely. An important element in Peters’s practice is about magic. In this gallery I am reminded that magic is often unseen and unknown: By distancing the vitrines and jewelry from the viewers, the mystery is either amplified if the viewer is receptive, or lost if that person refuses to open up to the nuances of the work and display. I am particularly drawn to the Sephiroth series. The brooches from the Sephiroth series are representations of the Kabbalah’s Tree of Life. The nodes in the brooches’ lattice structure—spheres formed in silver and glass—represent “emanations,” or revelations of the divine to man. This series pays a large tribute to mysticism (just as Corpus does to Christianity), and begs to be used as magical amulets. I imagine it could be similarly transformative to wear and embody the male energy promised by the huge phallus pendants in the Lingam series. The body activates the jewelry, but we are denied the immediacy of touch in this installation. As suggested above, that denial is part of the mystery. Again, the viewer has the opportunity to accept this or feel frustrated at being denied such powerful amulets. It is dependent on how we read the vitrines—as a veil between the sacred and the profane, or as an expected security measure.

The unconventional installation is engaging, yet it does diminish the accessibility to the jewelry itself. Those visitors not able or willing to lower themselves to the ground will miss the exhibition almost completely. An important element in Peters’s practice is about magic. In this gallery I am reminded that magic is often unseen and unknown: By distancing the vitrines and jewelry from the viewers, the mystery is either amplified if the viewer is receptive, or lost if that person refuses to open up to the nuances of the work and display. I am particularly drawn to the Sephiroth series. The brooches from the Sephiroth series are representations of the Kabbalah’s Tree of Life. The nodes in the brooches’ lattice structure—spheres formed in silver and glass—represent “emanations,” or revelations of the divine to man. This series pays a large tribute to mysticism (just as Corpus does to Christianity), and begs to be used as magical amulets. I imagine it could be similarly transformative to wear and embody the male energy promised by the huge phallus pendants in the Lingam series. The body activates the jewelry, but we are denied the immediacy of touch in this installation. As suggested above, that denial is part of the mystery. Again, the viewer has the opportunity to accept this or feel frustrated at being denied such powerful amulets. It is dependent on how we read the vitrines—as a veil between the sacred and the profane, or as an expected security measure.

For those familiar with Peters’s oeuvre but not with his shows, Ground is an opportunity to experience his jewelry within his curated environments. For those new to his work—perhaps the young metalsmiths at MassArt or the administration—the exhibition provides a launching point to examine art jewelry in a manner rarely employed in traditional gallery spaces. We are treated to a corporal experience that asks us to move our bodies closer to the ground to see the work, marrying our physical bodies with Peters’s conceptual objects.