With Nhat-Vu Dang, Jantje Fleischhut, Gésine Hackenberg, Iris Nieuwenburg, Evert Nijland, Ted Noten, Ruudt Peters, Lucy Sarneel, and Manon van Kouswijk

This is the third in a new series called “in Sight.” We have asked a maker, a curator, and an historian to discuss From the Coolest Corner, an ambitious event that was just launched in Oslo, Norway. Märta Mattsson reported on the event as a visitor and exhibitor; Love Jönsson, who juried the main exhibition, took our written questions; and Liesbeth den Besten, who curated one of the shows, responded to a Skype interview after returning from Oslo. Mattsson, Jönsson, and den Besten went to Norway with a different job to do and together their reports produce a varied and complex snapshot of the event. We hope their overlapping voices, as well as those to come in this series, stir vigorous debate.

Since 1985, art historian Liesbeth den Besten has been an independent writer, curator, advisor for governmental institutions, jury member, exhibition maker, and lecturer in the fields of craft and design, and especially in contemporary jewelry. She teaches in the jewelry department of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie (Amsterdam, Netherlands), is chairperson of the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation, and recently became a board member of Art Jewelry Forum. In 2011, den Besten published On Jewellery, a compendium of international contemporary art jewellery (Arnoldsche Art Publishers). She was part of the jury for From the Coolest Corner.

Liesbeth de Besten: The FTCC team actively encouraged commercial galleries and artists to organize satellite exhibitions that would be part of the program. FTCC did not commission Below Sea Level, Galleri Format did. Their first brief was for me to curate an exhibition of Dutch jewelry, and my initial proposal was for a show of young Dutch makers, recent graduates, in dialogue with their New Zealand peers. After being “discovered” by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642, cartographers named New Zealand after the Dutch province of Zeeland. It seemed interesting to use that historical connection as a springboard to compare the two countries’ very distinct creative paths. I also find that Kiwi jewelry is extremely fresh and wanted to showcase it alongside the more established Dutch vocabulary. In the end, the gallery preferred a show with household names, so I dropped the young makers idea. After all, I was quite happy about this because the Netherlands/New Zealand idea was much too easy.

The title Below Sea Level is similar to From the Coolest Corner in that they both proclaim a sense of place, indirectly, but pointedly. Yet, reading the introductory text to the show, it seems that you fought hard against the notion of a Dutch style. Was your ambition to challenge the notion of place or provenance as curatorial criteria?

I wanted to work my way through this notion of Dutch-ness, and unpick it. I didn’t want to look for a Dutch style, but I was interested in investigating whether there is a certain Dutch attitude. If it does exist, what is this attitude? I have been studying Dutch jewelry for years, and it possesses some qualities that seem very Dutch to me—a conceptual attitude; a capacity to go deeply into a chosen subject; a taste for long research; and a tendency to not easily be pleased. Arguably, this has less to do with culture than with training. Most of the artists in this show went to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, probably a more formative experience for these artists than the country they grew up or live in.

But it is not without reason that the Netherlands gave birth to a designer/artist such as Gerrit Rietveld and a famous academy carrying his name. You must remember that the Netherlands was reclaimed from the sea. This is an artificial country, basically fabricated by the people who live in it. Nature is not our friend. It consists of a lot of water that must be pushed back and contained. I think this explains the Dutch mentality. The Dutch are resilient people who are used to shaping their environment to their needs. This pro-active creative bend was allowed to blossom until recently. Throughout the 80s and 90s, a number of grants were made available to even the more radical sort of art projects. The government had a very supportive arts policy. The sense of creative freedom that resulted from this attracted a number of makers to Holland, such as Gésine Hackenberg, Jantje Fleischhut, and Suska Mackert.

For me, it was quite an experiment to even contemplate the notion that there is something typically Dutch in jewelry from the Netherlands. We are not used to this kind of question. But the Nordic brand and its current dissolution were the incentive that made me more aware of issues about place and culture. I think it is a subject that needs more research.

If it was, then I think it failed. In the large group of makers featured in the FTCC program, there are some people who cherish craftsmanship in the sense that they favor the use of silver in generally minimal designs. This, in a way, is (or was) a Nordic trait. But by and large, the works showcased in the event belong to the “international fusion” style, as I like to call it. There is a cliché of contemporary jewelry that the younger generation can easily adapt to and emulate. Which is not to say that they produce bad work—it is, in fact, often pretty good—but it just feels self-similar.

I do think that FTCC was a form of power statement. While few graduates from Oslo have received international recognition, Norway and some of its neighbors are flexing their financial muscles in order to establish a Nordic presence on the international scene. This means giving the Oslo National Academy state-of-the-art equipment, funding the publication of monographs on local artists by Arnoldsche Art Publishers, and staging an event like FTCC.

I have often heard you speak about an “international fusion” style as a type of rather rootless and homogeneous jewelry, but never of a “cliché of contemporary jewelry.” Do you mind describing what you mean by that?

What comes to mind are practices that focus on wearable objects made by gluing, taping, or binding together abstract bodies. It’s a form of assemblage that usually produces OK objects but tends to be bland. Only a handful of young people actually manage to turn this process into a language that is recognizably theirs. Beatrice Brovia is one example.

There is a lot of copying around, conscious or unconscious, which results in abstract, neutral things. I think makers should devote more time to thinking about what jewelry is. Jewelry should grab you somehow, and you can’t achieve this by joining in some kind of accepted style or way of working. I would love to see more resistance or saucy attitudes on the part of jewelers, not only in the Nordic countries, but everywhere.

What makes Noon’s and Nhat-Vu’s work singular is a different way of approaching jewelry. Both have an eye on fashion. Nhat-Vu—who, incidentally, was brought up by first generation Vietnamese immigrants, but clearly identifies himself as Dutch—designed his recent series of brooches with specific garments in mind. (He liked the idea that they would be worn on pure white blouses from COS shops.) His brooches are intriguing in the same way some of Warwick Freeman’s work is. They look like signs or symbols without a given meaning, like blank placeholders in a library of forms still waiting to be assigned a message. You have the feeling you can read them, which is very appealing for a writer like me who is working with symbols and signs on a daily basis.

The younger generation, of which Nhat-Vu is a good representative, is probably less concerned than their elders about social, political, or cultural issues. To put it differently, they are more interested in producing work that dialogues with fashion or youth culture than, say, tackling the representation of Christ (Peters) or the commodification of art (Noten). This generation travels a lot, or some of them do, and has a lifestyle that is decidedly urban and cosmopolitan.

The FTCC event as a whole questions whether someone’s origin (or background) informs the originality of his work. How was the question addressed during the FTCC seminar?

I wonder if you can say that the FTCC event really questioned the relationship between place and characteristics of work. Well, the question was addressed in some lectures, for instance in my own. But “Nordic” is a given. It means Scandinavian and some other countries in the northern European region (Finland, Iceland). Obviously, there have been connections between these countries for centuries, and they share an often-complicated history. They occupied one another, trade with one another, and more recently have begun to cooperate together. There is also a linguistic similarity between Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian. “Nordic” is a good brand. It sells. But, there are differences and local idiosyncrasies that can’t be explained through this label.

Nordic has been a way to bring artists and objects from different countries together, and maybe also to establish a feeling of belonging. The first two Nordic jewelry exhibitions only traveled in Nordic countries. The first exhibition was organized in Copenhagen in 1995. It showed typical Nordic jewelry with an emphasis on metalwork and a restrained Modernism or a cautiously accentuated Post Modernism. In 2001, the second Nordic jewelry exhibition showed work in the same vein. FTCC is the third Nordic jewelry exhibition in a row, but it is the first one that puts Nordic jewelry on the world map of contemporary jewelry. It is also the first one that has liberated itself from the Nordic paradigm, for better or for worse.

And now, it even seems that people are a bit tired of talking about Nordic. Unfortunately, the discussion during the last day focused on “the Nordic” in a rather perfunctory way. It was far less interesting than the thought provoking and rather pessimistic lectures delivered by Marjan Unger and Sofia Björkman the previous day. Sofia’s inspired lecture/performance did not leave much room for optimism. The gist of it was that nothing really changes, and she sounded rather despondent about the future of the field. I would argue—and I would have liked a debate around this fact—that there are new, interesting developments in the field today. I am particularly excited by the amount of effort going into photography and exhibition design, into creating context around one’s work. For example, some years ago Tanel Veenre used old secondhand doors to divide the exhibition space at Platina in Stockholm. This ingenuous setup does something to the space and also to the work.

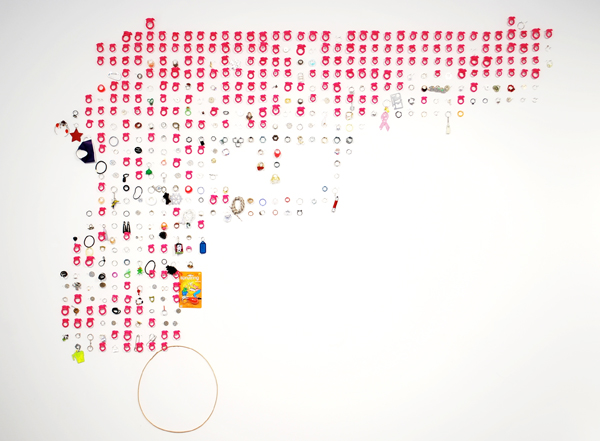

These strategies were exceptionally rare 40 years ago, although the first impulses were obvious in the work of Bakker & Van Leersum, Skubic, and Künzli, to name a few. Today’s makers increasingly view exhibitions as a medium. You can see examples of this in Below Sea Level. I deliberately created a stage for this phenomenon by inviting Atelier Ted Noten and his “ring swapping” project and by letting Ruudt Peters and Iris Nieuwenburg use display strategies that are specific to each maker but widely different. I wanted to stress the importance of context.

In her lecture, Marjan Unger voiced her concerns about the future of the jewelry market. What started as a protest movement shows no more progress, and it has become a secluded niche insulated from debate. This causes her to think that our field is a sinking ship. A different way to look at this problem is to acknowledge that the European jewelry scene is going through a transitional period. Some galleries will close, for sure, but some makers have already decided that the gallery system is not suited for them and are trying alternative strategies (Dinie Besems and Jorge Manilla, for instance). The artist-led projects they mastermind modify the way we encounter contemporary jewelry, and I don’t think this is a bad thing. The satellite program at FTCC was a good example of this new phenomenon and of the growing self-confidence with which artists manage their own projects. I am thinking, for example, of Nanna Melland’s Swarm installation at Deichmanske hovedbibliotek, a public library. Visitors were invited to donate a small amount of money, take an airplane brooch from the wall, and pin it on their garment.

According to Marjan, it is not cool at all to join a movement that is collapsing. But, I wonder how much of this doomsday scenario is true. The fact that the situation is changing in countries such as the Netherlands, where the movement started, doesn’t mean that contemporary jewelry has come to an end. We are facing the “law of the handicap of a head start,” (Dutch: wet of de remmende voorsprong, Jan Romein, 1937) or “dialectics of lead.” Soon, other continents will take the lead. Jewelry schools or higher educational courses are set up in Latin America and even in Egypt, while in the Netherlands, less money is available for good, focused jewelry education. We don’t even offer an MA in jewelry in the Netherlands. That is the reality of today. Marjan urged makers to stop viewing contemporary jewelry as a medium of pure artistic self-expression and to design wearable work with their own generation in mind. Both are interesting points, but I was frustrated that her (and Sofia’s) provocative statements did not serve as a starting point for an open discussion. Their lectures were clearly meant to challenge us, and there was not a good opportunity to respond.

As a matter of fact, I am not really frustrated by the fact that young people generally don’t wear contemporary jewelry. Contemporary jewelry is like old wine or classical music and opera. It takes time and some maturity to understand it. If you are young, have a family with small children, and are working hard, you have things on your mind other than a nice brooch or necklace. Of course, it is important that makers also strive for designs that are more streetwise and more sexy and explore ways to design and produce jewelry that is more affordable. I think this is the real challenge of today. But in my view, there is room—and a need—for both attitudes, even in the work of an individual artist. And for the rest, we have to reconcile with the reality that contemporary jewelry is a small artistic field and will stay small in the future.