De Keerzijde, Bloemlezing CODA Collectie

June 27–October 6, 2019

CODA, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

De Keerzijde, Bloemlezing CODA Collectie (The Reverse Side, Anthology from the CODA Collection) is the first exhibition by CODA’s new jewelry curator, Vanessa de Gruijter, who started the job in January 2019. With her first show at CODA, de Gruijter focused on an interesting and daring theme to kick off her curatorship: the hidden side of contemporary jewelry.For the first time, the reverse side of jewelry plays a dominant role in an exhibition. Normally this side is a secret best kept by the wearer of the jewel or by the gallerist or museum worker who handles the pieces. Only they know that some jewelry artists pay a lot of attention to the rear side—sometimes as much as to the front, or even more. The reverse is the most intimate part of a jewel: It’s worn closest to the body and most of the time hidden from the viewer. It’s interesting, therefore, to have this exhibition focus on the most intimate and normally hidden or secret side of jewelry.

In the Van Reekum Galerij, the permanent jewelry section at CODA, which consists of 10 showcases designed by Ward Schrijver in 2016, almost 80 pieces of jewelry from the CODA collection are on show.

The displayed jewels date from the last five decades and are made by 45 different artists. Ninety percent of the jewelry was made in the 21st century. Two brooches by the Dutch artist Peggy Bannenberg (1960) date back to 1988 and 1989, and two brooches by the Dutch artist Robert Smit (1941) date from 1989 and 1998. The oldest pieces in the exhibition, three silver brooches by the Dutch artist Onno Boekhoudt (1944–2002), date back to 1970.

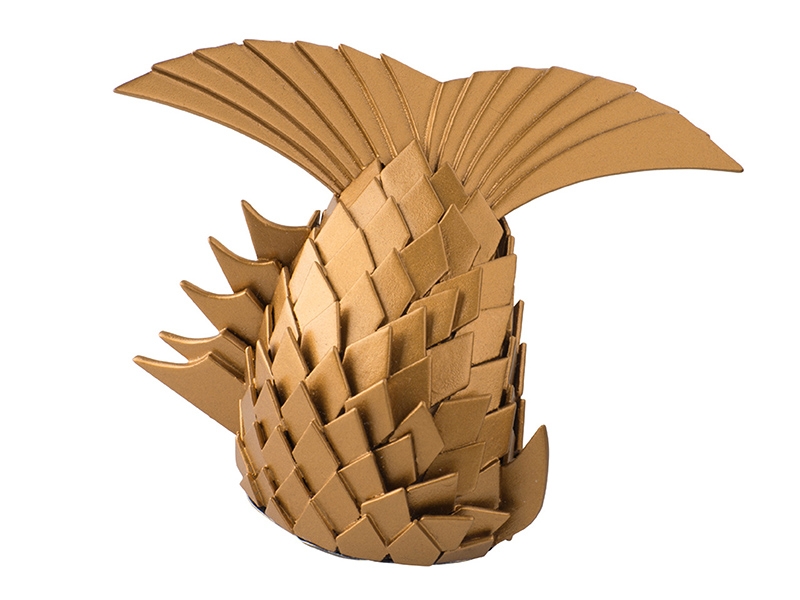

The jewels, mostly brooches (69 of them), a few neckpieces (7), and just one bracelet (The J. Russels (2008), by Felieke van der Leest) and one 3D-printed ring (Ice Flower (2015), by Beate Eismann) are on display with mirrors placed in such a way that the rear side is seen first. The front of the jewel can be viewed in the mirror. The pins which hold most of the jewels in place are unfortunately a bit distracting, because with the brooches they sometimes look like as if they’re part of the closure mechanism. These pins are especially problematic in the display of the monumental plastic brooches by Benedikt Fischer (Sennae Sannae and Vulpinus Vulpinus, both made in 2011), consisting of fragments of hard hats with functional metal on the back side. It’s great to notice that most of the newer pieces in the CODA collection aren’t ruined by permanently fixed inventory numbers, which is (and I hope we can put it in the past and start saying “was”) common practice in museums. For the depot, a label with a number and a barcode attached to a cord will do.

A few jewels are displayed with magnifiers that look like robots. Those magnifiers are even more distracting than the pins because of their obvious presence, but they offer a view of details which aren’t visible to the naked eye, which of course is always interesting.

The exhibition is centered around three themes: functionality (Functioneel), signatures (Signeren), and an intimate gesture (Een intiem gebaar). The choice for the themes seems a bit random and one needs to have the museum handout close at hand to discern the differences. Maybe a bit more diversity in the colors of the backgrounds in the showcases could have emphasized the differences between the subjects. Or maybe it wasn’t even necessary to group the jewelry into these three themes.

The brooch Corpus-Ovarium, a sliced depiction of the crucified Jesus Christ by Ruudt Peters, is interesting: The back has more details than the flat front. However, there’s no explanation anywhere why Peters made the brooch this way. It would have been interesting for visitors to read why the artist made this choice. And why is this black brooch placed in the functional section? The hanging brooch Something Terrible Happened (2010), by Artemis Valsamaki, raises questions as well: What’s special or functional about its back?

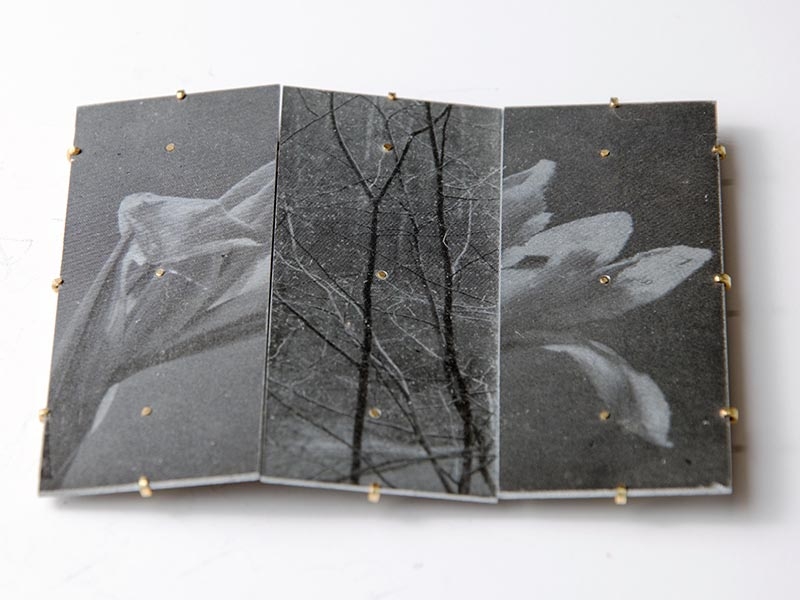

The rear side of Terhi Tolvanen’s brilliant brooch Opus Liberus (2007) is a big contrast with its front. The reverse, with its surprising rhythmic mirrored composition, gives a good reason to place the jewel in the intimate gestures section instead of the functional one.

A lot of times, the rear side is used for signatures, titles, hallmarks, dates, and of course brooch mechanisms, especially in more traditional and common jewelry made of precious metals and precious stones. Perfectly matching boxes for the jewels made by Lucy Sarneel, Ramón Puig Cuyàs, Herman Hermsen, and Beppe Kessler are shown as well. It’s nice to see the mirrored rhythm of the pieces together with their containers, but an explanation of the added value is unfortunately lacking.

Most pieces in the exhibition date from this millenium. A lot of jewels by Herman Hermsen are on display: four brooches and three necklaces. The front side of his Mona Lisa necklace is literally connected to the back because the three-dimensional neckpiece he depicts on the lady forms part of the strand used to wear the pendant itself. But it’s a bit strange to have so many Hermsen brooches—four—on display: Their almost blank wooden back sides with the same clasps and the same way of writing the signature presumes a greater amount of attention paid to the front sides. The heavy emphasis on Hermsen’s pieces is not entirely clear. It’s also a mystery why one of the two brooches (both made in 2015) by Petra Hartman has its monogram, PH, shown upside down. And in the signatures section, almost all the pieces are made by Dutch hands: It’s hard to believe that only Dutch artists use the back for signing their names.

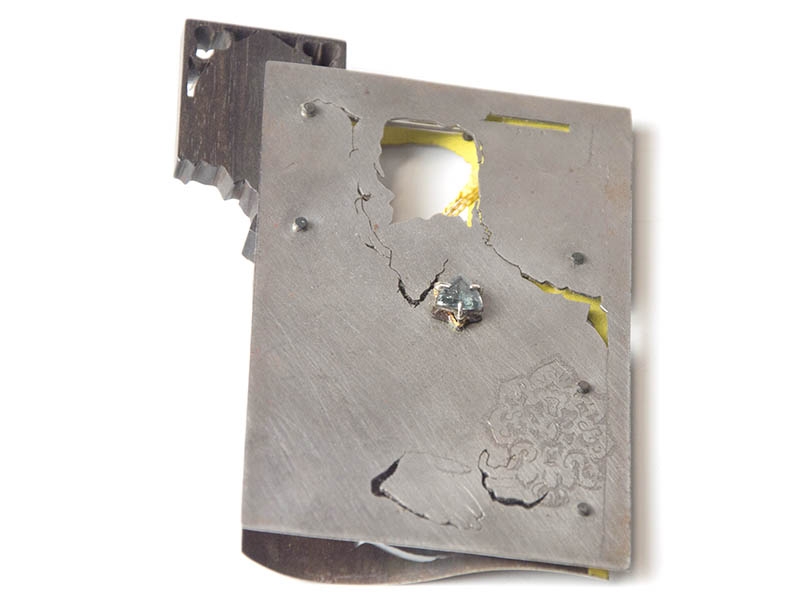

The intimate gesture section demonstrates how the reverse sides of some pieces compete with their front sides. Evert Nijland’s Moss brooch (2012) has a depiction of an Old Master print by the Italian Giovanni Battista Piranesi on the reverse, made of steel: It’s an entirely different and contrasting scene compared to the front, which consists of old weathered wood and glass.

Almost half of the included artists have Dutch roots or are strongly connected to The Netherlands: They lived, studied, worked, or taught there for a considerable amount of time. German artists, too, are well represented. It’s not entirely clear, though, whether the focus on the rear side is a European concern.

It would be helpful for visitors if the museum could assign numbers or icons to the 10 showcases: It would improve the use and reading of the handout (a free printout is available at the show). Maybe QR codes or (free) audiotours would be useful as well.

The show De Keerzijde, as an anthology from the CODA collection, displays quite a few masterpieces of the museum’s recently collected jewelry. The choice to show the unexpected side of the work is fresh, daring, original, and promising. It makes me curious about the future, and I look forward to more exhibitions curated by Vanessa de Gruijter.

A slightly modified version of this article will be published as an editorial on hedendaagsesieraden.nl.