Susan Cummins: Tell us something about this new gallery space called R|R Gallery in New York. Do we finally have a contemporary jewelry gallery in the big city?

Bella Neyman: Yes! This is very exciting news. R|R Gallery, also known as the Gallery at Reinstein/Ross, is located at 30 Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District. The name Reinstein/Ross may be familiar to many AJF readers because it is a New York institution. Susan Reinstein and Brian Ross opened the store in 1985. Susan designed the jewelry and Brian sourced the stones. Every piece was made in their Madison Avenue shop. Nancy Bloom and Andrew Schloss have since taken over the store, but have stayed true to Susan’s designs and also to the original owners’ core value: All of the jewelry is still made in New York City. The store has two locations, one at 29 East 73rd Street and the other one now on Gansevoort Street (until recently their downtown location was on Prince Street). Next year marks the company’s thirtieth anniversary and as they look to the future, the owners have chosen to open an art jewelry gallery. This stems from having employed many talented goldsmiths, who are alumni from some of the top metalsmithing programs in the country, so they are very familiar with the field and believe in it. The field is expanding and gaining worldwide recognition, and they want to be a part of this.

Susan Cummins: Tell us something about this new gallery space called R|R Gallery in New York. Do we finally have a contemporary jewelry gallery in the big city?

Bella Neyman: Yes! This is very exciting news. R|R Gallery, also known as the Gallery at Reinstein/Ross, is located at 30 Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District. The name Reinstein/Ross may be familiar to many AJF readers because it is a New York institution. Susan Reinstein and Brian Ross opened the store in 1985. Susan designed the jewelry and Brian sourced the stones. Every piece was made in their Madison Avenue shop. Nancy Bloom and Andrew Schloss have since taken over the store, but have stayed true to Susan’s designs and also to the original owners’ core value: All of the jewelry is still made in New York City. The store has two locations, one at 29 East 73rd Street and the other one now on Gansevoort Street (until recently their downtown location was on Prince Street). Next year marks the company’s thirtieth anniversary and as they look to the future, the owners have chosen to open an art jewelry gallery. This stems from having employed many talented goldsmiths, who are alumni from some of the top metalsmithing programs in the country, so they are very familiar with the field and believe in it. The field is expanding and gaining worldwide recognition, and they want to be a part of this.

Ruta Reifen: Wear It Loud implies adorning oneself with a “statement piece,” a term often heard in the fashion world. This title suggests the selection of original, skillfully crafted, and concept-based artwork that engages in a direct dialogue with fashion as a discipline. Denise Reytan’s collage-like neckpieces—bright, bold, and aggressive in scale—are a perfect example of what “wear it loud” stands for.

What is the behind-the-scenes story of how you became engaged with the gallery? Did you propose the idea of Wear It Loud to them?

Bella Neyman: I heard through the jewelry grapevine that a new gallery was opening and decided to investigate. I met with Andrew and Nancy to discuss the new space and we immediately clicked. They said that they were looking for ideas for their inaugural show and I told them to look no further. This was about six weeks before the space was opening, and Ruta and I started working on Wear It Loud that same night. We were really honored that they believed in us and trusted us with such an important project.

The idea of holding the show during fashion week and trying to relate the contemporary art jewelry to fashion jewelry sounds great. But how did it play out? Did the fashion world come for a look?

Bella Neyman: We did have some stylists present on opening night. We were also thrilled to get attention from non-jewelry publications. I do not think that we will see stylists featuring art jewelry in magazines right away, but at least I hope that we inspired them and can help them start the conversation and make connections.

You have defined five distinct categories for the work. Can you tell us what they are and how you arrived at them?

Ruta Reifen: Once we selected all of the work, we looked at everything as a whole and saw that a lot of the pieces were not only in dialogue with each other but had a lot of similarities in terms of the themes. Most of the work could have easily fallen into more than one category. The five categories we identified were:

- Artists who reinterpret vintage jewelry (most often seen in fashion editorials) through the use of nontraditional materials

- Artists who are inspired by the portrayal of jewelry in fashion magazines

- Artists who through the deliberate use of photography have staged their own editorials

- Artists who subvert the logos of popular fashion houses to create original work

- And artists who create jewelry that is an extension of the garment

Which artists fell into which category and can you describe one piece of jewelry in each of the five sections as a visual example?

Most of the artists we featured reinterpret vintage jewelry through the use of nontraditional materials. I think the way Nikki Couppee paints Plexiglas with nail polish to achieve the beautiful bold colors of the gemstones seen in every glam editorial shot is a great example of thinking outside the box. In fact, Nikki told us that fashion editorials were her primary form of research. The wide array of nontraditional materials really surprised and delighted many of our visitors. Tara Locklear’s use of cement to make “costume” jewelry was another hit.

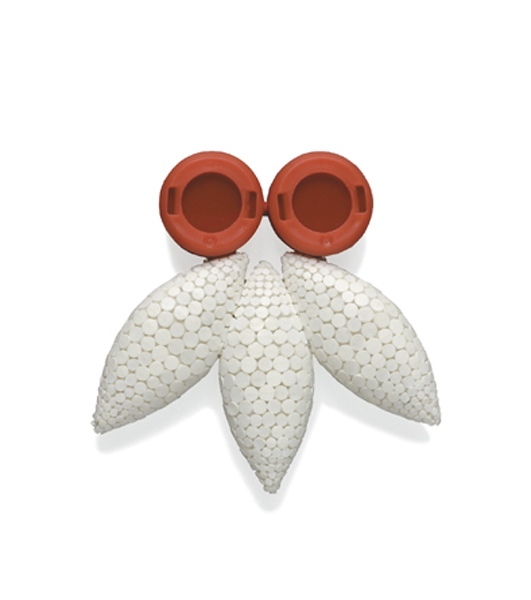

It was fun to bring in pieces that could potentially challenge the viewer’s perception of jewelry. Johanna Törnqvist’s neck collar Vingklippt (Pinioned) is made from packing materials, mesh from a wine bottle sleeve, a gym ball, oilcloth, a crochet table cloth, and cotton ribbons. It is pleated and stitched together with the same precision as an haute couture garment. Mia Kwon’s porcelain neckpieces that mimic dress collars also blur the lines between garment and jewelry.

We also loved the photos of the artists wearing their own work, like Lola Brooks or Hanna Hedman. The imagery is so strong and impactful. In both of these cases, as when you see fashion designers modeling their own clothing, you are trying to replicate the artist’s look and by owning a piece of their jewelry you are hoping to become them. Artists are no longer just focusing on making good work. They are also thinking about how to market themselves. Very similarly to the way that fashion designers need to consider their image, so do artists.

Did your promotion and display for the show use a fashion-oriented strategy for attracting the fashion crowd? If so, was it different from the contemporary art jewelry approach?

Ruta Reifen: Platforma’s mission is to expand the audience and collecting base for contemporary jewelry through alternative outlets. Here, our strategy was to utilize a conventional white-walled gallery space with a simple display to play up the “loud” aspect of the jewelry. We wanted the work—not the display—to drive the conversation, although it was beautiful. Working with a gallery in such a central location allowed accessibility to a diverse audience that is new to this subject. Additionally, we chose to project images on the gallery wall. The selected images were editorial-like in quality and choice of composition, much like photo shoots featured in high-end fashion magazines. This has become a trend in contemporary jewelry documentation. By promoting work photographed in this manner, we called attention to the increasing crossover into the fashion world.

Thank you.