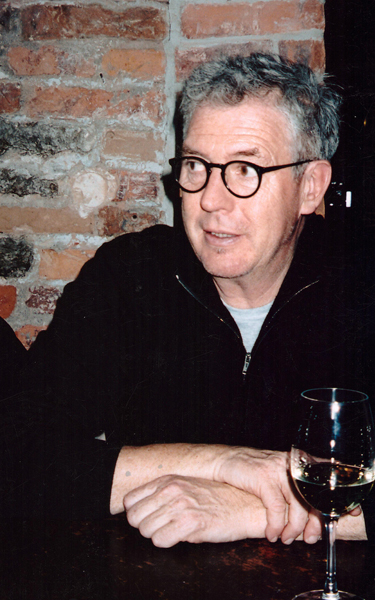

—Manfred Bischoff

Kadri Mälk: You seem so uncompromising in your work and life; how have you achieved that?

Manfred Bischoff: Uncompromising? —Not really.

I am absorbed in these situations and it’s OK, I accept this. It’s not a will, how can I put it, it’s much softer, much … I didn’t decide my ways myself. Uncompromising might be only the fact that I’ve accepted the situation. That I’ve not struggled against it. My life seems to me as a private logic for myself but not made by myself. Please don’t misunderstand me. I’m not an esoteric in the strict sense. But looking back, I always think—phhhhh, strange. If I would have said NO at that time, what could have happened then? I’m somebody who accepts what is meant for him to happen. I’m not uncompromising—not at all, and I’m not a … warrior.

Have you rejected many things?

Have you rejected many things?

Manfred Bischoff: Yes. Many.

The question about intransigence sounds interesting, and some people think that I am uncompromising. I am not … in my case, no will has been involved.

It just happens?

Manfred Bischoff: Also not. It means not wanting. Not really.

But also not neglecting?

Manfred Bischoff: Look, if I speak about myself, I have a problem—either I make myself strong or I make myself weak. And I don’t want to speak about either. Because my position is in the middle and about this I cannot speak.

I saw for example an exhibition of Gerhard Richter in New York, he deconstructs, and he was asked if he could say something about his pictures and he said some sentences … and I thought—this man should be the best-sold artist in the world, and later I reflected—an artist who deconstructs can never add anything, so if he said about his pictures something important, his pictures would never be credible. In my case, either I get in a situation where I position myself in the center—or—I’ll be an asshole.

But as a matter of fact, I should talk about the center—but I can’t. Because talking about the center would mean talking about my work, and that’s something I would not like to do. I do not want to grip the work with language.

If I leave my work in peace, that’s the best. If I speak about my work I can only hide it or deride it. I do not speak about the Between, otherwise it’s no longer the Between.

So—I surround my work with something, and don’t ask me questions about that.

When the work has been completed, can you distance yourself from the piece, so that you have no more spiritual connection with it?

Manfred Bischoff: Yes, that’s right, because I divide absolutely between an object and a subject. As long as I’m involved in this work … I’m also not very involved … but I always see it as an object, and… Look, some people are so disappointed if their works are not in the position they think they should be.

I’m not interested in this because it is just an object, an aim … I do not mix an object with my personality.

So you keep the distance?

Manfred Bischoff: It’s not a distance, it’s totally elsewhere. It’s not a question of bigger or smaller distance, it’s totally out. It must change into money and money must change into new aesthetics … that’s the circulation. I told you I only want it to be documented.

Just to preserve it in your memory?

Manfred Bischoff: Yes, perhaps also this can be too much but I’m not such a great artist who can say it’s all the same for me, is it documented or not. No, not so.

But being here does not mean that I leave no trace at all. It’s a circulation.

When have you been most happy about your work?

Manfred Bischoff: A hippie question! I’m not happy about my work. Only if all circumstances around function, if my dogs are well, and …. no, I think on the whole I have been successful and I like it when I’m not too much involved in this. I do my job—basta. I would like to do more, but … it is as it is. I’m not a warrior.

The reflection comes later. I don’t have such a strong wish and I try not to have too strong a wish, until ….

But my gut feeling tells me that if there’s a distance and I see things from a righter place, higher place, then nothing matters so much anymore. For a viewer, for an observer who sees it for the first time—perhaps it matters. But I don’t think I regard myself as especially important. Importance is totally beyond my wish, will, and wanting.

Space. And time. I like time very much, also the chance to see if what you have done has a substance … So at the beginning you can be enthusiastic about this … I’m no longer enthusiastic … there was a time when I was … searching for myself, for self-affirmation.

But I can tell you now that the most … satisfying and beautiful for me is the—distance. When the importance you have given to the pieces is getting smaller and smaller. Then my work has substance for me. As long as your work is so important and stays in the foreground, it’s nothing for me, it’s bad.

No—disappear, disappear, disappear … Then there is more space to create other things.

Its like in Buddhism, you have to lose yourself, your Self.

Manfred Bischoff: Yes. Perhaps so.

There are many artists in contemporary jewelry who complain that the field of jewelry sounds like a closed diaspora, the circle of people who are interested in contemporary jewelry is not really large, this kind of inside-feeling, which may be quite worrying. Is it also your problem?

There are many artists in contemporary jewelry who complain that the field of jewelry sounds like a closed diaspora, the circle of people who are interested in contemporary jewelry is not really large, this kind of inside-feeling, which may be quite worrying. Is it also your problem?

Manfred Bischoff: Not for me. I can understand that they get worried. Because they expect so much.

You don’t?

Manfred Bischoff: What should I expect? I cannot … project what doesn’t exist. What should I expect to happen? Or should happen? I’m very clear about some things … I do not look for what is behind this door if I do not know what is behind this door. I really do not expect anybody to come to this door. I look at what I see, that’s all. What I mean is … is what I mean.

So I define my reality only through what I see, I get a call and I get a letter, not silly things like viruses … such stupid things … it’s speculation, it’s a thing of mistrust … you don’t trust. No, it’s also not true, it’s …

Could you say a few words about the students you have at Alchimia school?

Manfred Bischoff: They are young and I try to keep them innocent, I want to have them as children, not as adults, that’s the whole practice of the Alchimia school. We love them and hope they love us. There shouldn’t be fear in working.

To make them stronger?

Manfred Bischoff: Make them stronger? More, to let them play.

We don’t move forward. We don’t move towards a goal like … you must! … We do not say: you must become famous, and … that’s the only thing, yes, sure, but it’s not for me, in my teaching, I do not teach how to get famous.

What is essential in your teaching?

Manfred Bischoff: The essential lies in the students, I’m only a director. There’s a play of Pirandello—Six Characters in Search of an Author. So, why cannot we be the author, why cannot we be the play? That’s what I’m teaching. I only set the scene.

You choose the play?

Manfred Bischoff: No, I do not choose the play. They are the play, I’m the regisseur.

I tell them where they have to stand. They are the actors.

It’s also not teaching, it’s finding the right place. I’m not teaching.

I try to create different situations and look at this, if it functions or not. If they are in the wrong position, I try to find another one that would perhaps function better. That’s all.

Look, actors are so childish, my students too. And I mean this with a big mutual respect. When I say they are childish, I say it with full respect. I like that they’re like this.

What about the erotic side of teaching you mentioned?

Manfred Bischoff: Don’t expect me to repeat what I said to you.

A secret for two?

Manfred Bischoff: No, because this is a secret for two, yes. Because if I tell this, the erotic is gone. But it’s a part of teaching. For me the biggest part. Because in an erotic relationship the subconscious is revealed, they do things that normally in dialectical thinking they don’t. They do things in certain delirium, in a kind of between-ness, in a kind of twilight. And that’s very nice.

Erotic is mostly the first movement, the first start, the first impulse, vita vitale. Which starts life out of itself. I think if you take it manually it will not function. You must start metaphysically and the erotic is part of it.

I mean Eros. Eros is always the Between. But I like the unreachable situation where Eros can never be reached, that’s teaching. There is no wanting and no neglecting. To keep that balance.

That’s why I like this situation, they are like small cupids, I like the innocence of them. Because later they have enough time to deviate to one side or the other.

There was a show, Beauty Is a Story, by Yvonne Joring, in Holland. What does beauty mean to you?

Manfred Bischoff: It’s a problem I do not wish to discuss. Because it’s infinale, an everlasting story. I would not like to comment about beauty, might be I’m a creator of beauty but …

No, it’s not an important question, and other people can speak more about this.

Schönheit …. Beauty … No, it’s not a question for me.

What would be the question for you?

What would be the question for you?

Manfred Bischoff: Shall we finish?

Where is the exit? (Note: This is a quotation from MB’s book Üb Ersetzen)

Manfred Bischoff: That’s right! (laughs)

You are sneaky to put me a question like that. I will not answer your question about beauty, would not answer the question, “which would be the right question for you,” and will not answer your next question.

(some time passes)

You must not. You may.

Manfred Bischoff: There rises no question.

You can construct the question, or the question rises.

We can have pieces where no question is needed.

I have a student who asks me always: why don’t you say anything? What should I say when everything is OK, wonderful?

Why should we overload ourselves or ask … when I see something that is beautiful, I stay speechless.

The beauty shows itself in the silence.

Are there any “wrong reasons” in your professional life?

Manfred Bischoff: You can move from one place to an other and start immediately on a temporary bench, it’s your profession, a hammer and let’s go.

When I feel myself sure inside, it functions.

It was not my intention to become a goldsmith. My mother booked me into the goldsmith’s school, can you imagine! It was not me! My mother! What a terrible start. The most terrible start, when you mother decides upon your profession. So, from the beginning onwards, it was a terrible situation.

I had to convince my mother that I’m able to do that. To become a goldsmith. Not to convince me. So who would I have become if my mother hadn’t booked me into the goldsmith’s school? Everything could be possible. No, I had to become a goldsmith. I told her—a photographer, a scenographer—she told me: no, you go to study, I booked a place and you will become a goldsmith. It was not my decision.

Another question?

Have you thanked your mother?

Manfred Bischoff: Thanked my mother? Oh, God, no. No.

Do you feel that the decision has been wrong?

Manfred Bischoff: Not for my mother. But my father, he told me nothing. It was wrong. He didn’t say anything.

He was silent.

Manfred Bischoff: Yes. So I had to learn this profession. And … (Laughs.)

Yes! What shall I say!!!

One great artist has said that it took many years to discover he had no talent for art, but he couldn’t give it up, because by that time he was too famous already.

Does it count also for you?

Manfred Bischoff: For me? —No, I don’t think so.

Everything that pleases your mother is shit. I mean, in the psychoanalyses one can realize at once what it means. You cannot get rid of the Oedipus complex because you are making love to your mother. And I should make love to her for a long time because my father didn’t lead me out.

Why are you so figurative in your work? It’s not usual in contemporary jewelry. Artists are mostly much more abstract in their expression.

Manfred Bischoff: Because I don’t do things which I cannot name. I don’t like straight lines very much, I hate exact circles. There are simple signs and innocent signs, the more innocent the better … so that I should not hide myself … not veil … anymore.

My whole life has been a deconstruction. It’s easier to get into another world in this form than to lose yourself totally.

So I try to find simple images which I can name, which I can work with … which don’t thrill or menace me, which leave me in peace.

These are not so simple, your images.

Manfred Bischoff: Oh, yes, they are.

There are some animals in your work, one cannot really understand if it’s a pig or a boar or a reindeer, just an animal.

Manfred Bischoff: Ja, animal! —Animal, which means soul. I can handle these animals very well. So we should make them in gold.

(The shelf falls down with a tremendous crash.)

Look, it fell down when I said that.

You have quite a limited list of materials that you use in your work. Does it have a special significance that you use only high-karat gold, coral and jade, sometimes some diamonds? What’s behind that?

Manfred Bischoff: Behind is nothing. That’s the same thing I just spoke about, I killed the significance. The coral is there and behind the coral is nothing. Did you see something there?

Coral is like metaphorical skin, the structure of it, you feel it when you work with it, cut it and polish, how it peels off. And there is so much animalism in it.

Manfred Bischoff: For you! I never thought about that, it’s interesting.

So for you it’s just the color?

So for you it’s just the color?

Manfred Bischoff: I said I won’t speak about it. The viewer should decide.

I don’t like this light. (Moves aside, because the light is too bright.)

(Laughs sadly.) What are you making me tell you.

I do not kill my images with language. My titles are so far from what you see that I will say nothing about what I mean. I do not invent titles of what is seen. It would be a sin. Eine Sünde.

So the references should be hidden?

Manfred Bischoff: The reference is visible to everybody, but I don’t want to speak about it. I don’t want this to be a style or … how to say … kind of effect. I would not like to talk about it … a painter should also not be asked why he used pink in his work.

Madonna del Parto, exposed against the background of a drawing of coordinate axes, one of the most powerful works in your creation for me.

Manfred Bischoff: It’s a pathological piece, as I thought I could find here another exit … because … no, I will not talk about it …

(Laughs out loud.) … No, you will not get an answer from me.

(Long silence.)

The psychotherapist is dead.

Don’t answer.

(Even longer silence.)

I can wait.

Pazienza.

Manfred Bischoff: I don’t mind. But your sound tape will run out soon.

Would you like to say anything else?

Manfred Bischoff: No, I would like to go home.

This conversation took place during Passion Week, March 23, 2005, in Tallinn, Estonia. It was first published in art magazine Kunst.ee, 2005.3.

[1] From an interview of Manfred Bischoff by Pieranna Cavalchini, published in the book Manfred Bischoff, (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2002).