Olivia Shih: Please tell us about your background and how you became the curator for Matter of Material.

Madeline Courtney: I am an artist with an academic background in fine art, art history, and French. After college, I worked as the sculpture shop technician for several years at my alma mater, Kenyon College, where I developed a body of sculptural work investigating the relationships between object, animal, museum, and sculpture. This led me on a Fulbright Fellowship to Paris, where I took courses in museology at Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and researched the history of taxidermy in the city. I found taxidermy to be fascinating because it opened up interesting questions about material—how we relate to it, gain knowledge through it, and also how we manipulate it in order to re-create the world to our own vision.

Back in Seattle, I became involved with the local arts nonprofit Artist Trust, which is how I came to know Karen Lorene and interviewed for the manager position at Facèré. This opened up a whole new world to me—the world of jewelry art and its brilliant community of makers.

Working at Facèré, I have a hand in almost everything we do. So far I have helped produce and manage over twelve exhibitions at Facèré. Matter of Material is the second show that I have independently curated.

In Matter of Material, nine jewelry artists opt for alternative materials and eschew traditional precious metals like gold and silver. Was there a single event or object that sparked the conception of this exhibition?

Madeline Courtney: Facèré has always, with several exceptions, featured work that is primarily metals based. Focusing on nine different materials in this show allowed us to broaden the palette of the work involved. Each material introduces its own scale, weight, texture, and sometimes even smell.

The choice of a nontraditional material is not always a rejection of traditional precious ones. Gold, silver, and gemstones are still present in Matter of Material, although it is alternative materials that are forefront.

In my own work as an artist, I am drawn toward nontraditional materials. Different materials open up different modes of expression and identity. If you look at jewelry from Australia, Oceania, and Africa, which incorporates everything from bone to tree resin, you’ll find a different energy than exists in traditional Western metalsmithing. This power of material is something I see many jewelry artists exploring in their work, all of which inspired me to put together a show with this focus.

Why do you think jewelry artists are turning more and more to alternative, and often inexpensive, materials such as acrylic, paper, and cement?

Madeline Courtney: The inspiration for choosing one material over another is different for each artist. Choosing to work in alternative materials can be practical, ethical, poetic, or tied to personal affinity. It can also be all of these things at once. The idea of preciousness itself can mean many different things, and is not necessarily tied to concepts of expensive or inexpensive.

In today’s world, new materials are being explored and created every day. At the same time, many materials are becoming scarce or harmful to source. For many of us, concern over materials affects what we purchase, consume, and bring into our lives. It is something that we as a society are becoming more and more aware of. Artists are not excluded, and may be even more keenly aware of material matters because of the intimate relationship they have with their work.

In order to play upon society’s expectations, artists have been using alternative materials in subversive and mischievous ways for many years. I think of Méret Oppenheim’s fur teacup and how it toys with ideas of femininity. If we look thousands of years back, we see that people were wearing their surroundings and creating meaning through material before they could write, read, and maybe even talk. While material is not a new language, it continues to be a powerful one.

At first glance, the works of the nine artists seem disparate or almost conflicting. A second look reveals circular and chain motifs that run through the exhibition. What ideas led you to curate a cohesive show with so many distinct aesthetics and materials?

Madeline Courtney: When we invite artists to an exhibition, we assume that the majority of the work in the show is going to be created specifically for that show and guided by the theme or concept provided. There is always a degree of uncertainty and of surprise. For Matter of Material, each artist was invited to create a body of work based in a specific material with which they are familiar. We purposefully chose to represent artists working in distinctively different materials. In many ways, it is the disparate nature of each of the materials that makes them work so well together. They are different enough in texture, luster, and scale that they actually complement each other’s unique qualities.

Art jewelry has the ability to subvert traditional values placed on precious metals and gemstones, but how would you introduce the work in this exhibition to a person who has had no experience with art jewelry?

Madeline Courtney: Jewelry made from nontraditional materials instantly sets it apart from the norm. This can be an asset when introducing the work, because it makes it easier to understand the jewelry as art. The familiar nature of the materials can also provide a point of entry that is more accessible. Who doesn’t already have a relationship with wood or plastic? The known material in a new form can instantly create an interesting dialogue.

The major hurdle for nontraditional work is its perceived value. It is easier for the everyday person to place value on precious metals and stones. As art gallerists, we promote the value of ideas and artistry. We invite people into this world by making the work accessible and sharing our love of it with others. More importantly, we encourage people to try things on and to talk about the work. Building community through art is at the center of what we do.

Do you have any advice for emerging jewelry artists on making work or finding representation?

Madeline Courtney: My advice to emerging artists: The most important thing to make is studio time—time to try, fail, create, discover what you love, and return to it over and over again. Whatever that thing is, find different ways of incorporating it and interacting with it through your work. It is important to take your work out of the context. Share it with others. Take pictures. Build a website with it and see how it looks online. Find exhibition opportunities. The more ways you experience your work, the more you will understand what makes it your own.

For representation, research opportunities that exist or could be created. Each venue has its own personality—identify what that is and if it relates to your work.

Join a community through which you can meet and correspond with others in your field. Visit places in person and wear your work. If visiting is not possible, email. Emails with four to eight well-chosen images attached will quickly introduce your work and instantly give the gallery an idea of whether your work would be a good fit. Curate a portfolio that is well edited and that demonstrates a distinct direction and voice. Choose brevity and continuity over quantity. Share information on how you price your work. Familiarize yourself with the gallery’s policies and see if they are a good fit for you.

Member profiles, through organizations such as Klimt02 and SNAG, are a good tool through which to become more accessible to galleries. For inspiration when planning a show, I will often use those resources to discover new artists for the gallery. Creating important content—articles and interviews—for your field is another great way to get your work out there!

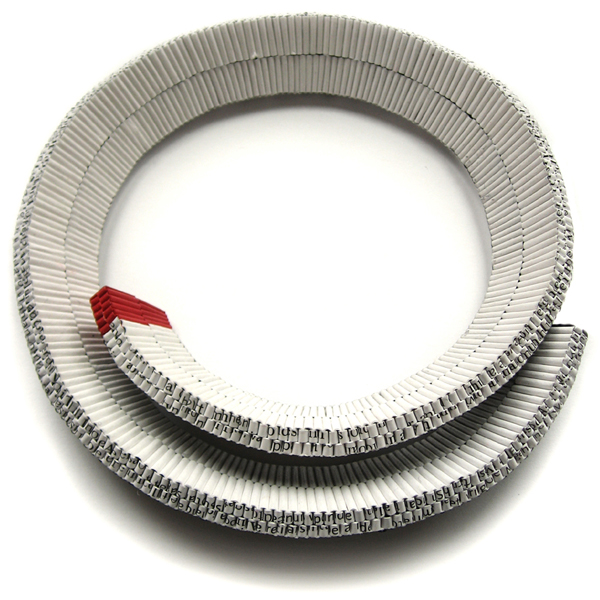

We’ll talk to some of the artists next. Francesca, your work transforms everyday material, such as book pages, into woven but minimal jewelry. Does your work as a biochemist influence the way you work as a jeweler?

Francesca Vitali: At first, when I started making jewelry, I was so concerned about the media I was working with and the fact that paper is not a precious material. I have a PhD in chemistry, and it is a totally different background that I didn’t give much thought to. But recently, I started making things just because they felt right, without overthinking the media or how to impress with my work, and I started to realize that indeed my chemistry background informs my work in a very natural way, so much so that it is instinctive for me.

Jennifer, how did you start working with acrylic to create jewelry?

Jennifer Merchant: I started working with acrylic a bit while I was studying metals and jewelry at the Savannah College of Art and Design. I played around with carving it, which I discovered was similar to carving waxes for casting, but I liked that it resulted in a finished piece instead of going through more steps as in the casting process. At the time I just made small pieces to attach stone settings to for my stone-setting class, and carved a pendant. I started experimenting with layering the acrylic with imagery after I graduated. When I moved back home to Minneapolis I was broke and had very few tools, so I didn’t feel I could make very interesting metal work in my modest home studio. I decided to work with things I had, so I made my first pieces out of Plexiglas I had left over from a failed attempt at making display cases for my thesis show, and my collection of fashion magazines. Five years later I had the layered acrylic technique down to a point I felt comfortable selling it, and I started my studio business in 2010.

What is the inspiration behind the graphic yet luscious pieces from your new Opulent Illusions collection?

Jennifer Merchant: The inspiration for the Opulent Illusions collection started when I carved my first domed form in layered acrylic last year. Until then I had been sculpting very angular faceted forms. I realized that the domed acrylic over images distorted them in really interesting ways. I am also really inspired by op art; I love how a static image can appear to have movement and trick your brain. I wanted to see what would happen if I took these optical illusions and further distorted them beneath domed acrylic forms. I have also been working with 23-karat gold leaf and layering it between acrylic; I felt the gold would be a great accent to the collection and add to the richness of the pieces and complement the softer forms with a gold glow, juxtaposed with the very graphic black-and-white illusions.

Checha, cement is integrated into the pavement we stand on and the buildings we live in, and artists such as Amira Jalet and 22 Design Studio have incorporated this inexpensive and ubiquitous material into jewelry. Why are you drawn to it?

Checha Sokolovic: My architectural background finds a new voice in my jewelry, as I explore familiar architectural forms and materials in unexpected scale. I find inspiration in polished concrete floors, board-formed concrete walls, old concrete pavements, and sidewalks. Through the simplicity of geometric shapes, I wish to reveal a hidden beauty and elegance found in the construction materials. I think of my jewelry as my miniature architecture.