Alternatives Gallery, located in the historical center of Rome, has met the challenge of selling to a relatively conservative clientele by being remarkably proactive in promoting itself and the field on a national and international level, and by launching no-gram, the first online gallery devoted solely to selling contemporary jewelry. Rita Marcangelo, the gallery director and no-gram co-founder, has kindly taken some time to discuss the many projects she has quietly and successfully led, and the challenges that came with them.

Benjamin Lignel: Rita, your gallery, Alternatives, has just become an AJF donor, and this interview is our first one: I see there an opportunity to look at the many platforms you have worked in, and the networks—both local and global—that you contribute to.

Let us begin with a beginning of sorts: You were born to Italian and British parents, grew up in London, trained in applied language studies at Thames Valley University, from which you graduated with honors in 1988, moved to Rome in 1990. How did you actually learn your craft? What were the challenges and opportunities in store for a jeweler setting up an independent practice in Rome at that time?

Rita Marcangelo: Well, I moved to Rome in 1990 without any real plans. I had started working as a freelance translator in those days and, although I loved what I was doing because it was what I had trained for, I felt something was missing. It is only when I met my husband, who is a jewelry maker, that everything fell into place. I was fascinated by his world and realized that I needed to do something with my hands. I was in search of another form of expression, a new language. Jewelry was an interest I never knew I had until then, at least not in an active way. It was an unconscious choice, one that my instinct had led me to. I didn’t have any formal training as a goldsmith but I learned the techniques that I felt were necessary to make my pieces and to be able to express my art. I also developed techniques of my own in working with alternative materials.

In retrospect, I think it wasn’t so important that I was making jewelry in particular, but the fact that I could express myself through a manual skill was primary to me at the time.

In 1997, you opened your first gallery, in the historical center of Rome. I can imagine that getting prospective clients to appreciate your delicate silk, metal, and paint experimentations was tough. Why the added challenge? Was there something missionary about that project?

Rita Marcangelo: Right from the very beginning, my jewelry pieces were seen as unusual and unconventional by Italian standards, but that didn’t seem to matter to me. I was concerned with expressing what interested me, without having to worry about the commercial aspect of things. The Italian scenario, with the exception of Padua, was still very traditional with respect to what was happening in the rest of Europe, and I felt I wanted to give my contribution in trying to change things, so in a sense, yes, mine was a mission of some sort. I decided to open a gallery with the precise scope of bringing the international world of contemporary jewelry to Rome, to a public that had still never seen such things. It was a huge challenge to take on, but I had the ambition of being able to remodel attitudes toward contemporary jewelry in Italy, or at least that of making an attempt in that direction.

One aspect of Italian city life is remarkable: Every quartiere (city quarter) has its goldsmith, to whom local families are used to bringing their custom work. They’ll buy birth medallions, wedding bands, but also bring things for repair. Did the habitual proximity of Italians to craft help you promote contemporary practice? Did it hinder you? Does this craft network of local makers overlap or compete with the very active Italian contemporary jewelry network?

Rita Marcangelo: First of all, I think a distinction between goldsmiths per se (orafi) and what are defined as artist goldsmiths (orafi-artisti) is needed. The people in the first group reproduce objects on the basis of a technical skill through methodical work and rarely further investigate through experimentation. The second group of artist-goldsmiths, on the other hand, (we can take Padua as an example) through a precise knowledge of goldsmith techniques and materials, experiments and creates objects that reveal artistic qualities. The category you are referring to is the first of the two. Most cities and towns are permeated with goldsmith shops of this kind which, although quite rare elsewhere, are very common in Italy.

No doubt, craftsmanship in the form of a service alone made the understanding of contemporary jewelry more difficult to start with, because people here were accustomed to considering a goldsmith more in terms of someone to refer to for something to be repaired or custom made, rather than an artist. This was undoubtedly a disadvantage for us, at least initially, but on the other hand, it also became an advantage in the long run, because it underlined the differences and so all those in search of something special would come to us.

Can you tell us about the original roster of artists? How did the Romans react to their work?

Rita Marcangelo: I recall the very first comments from people looking at the window and wondering what exactly they were looking at. Nevertheless, although this was somewhat of an initial challenge, in time the public realized that if they were looking for something out of the ordinary, they were in the right place. We became a reference point both at a local and national level. It can be quite gratifying, especially when people are initially skeptical about this type of art and later become great followers, even collectors. There have been clients, over the years, who initially had a quite timid approach in their choices, but have in time become fascinated with this world and have ended up buying works that make a statement.

In 2004—you apparently did not have enough on your plate—you co-founded the Italian Contemporary Jewellery Association [AGC], which aimed to channel a wide network of makers into one cohesive and self-supporting organization. It is, to this day, one of the largest and most active “national” associations I know of in Europe. At this point in your life, you were a maker, a dealer, and would be the director—for six years—of a large association. How did you negotiate these different roles?

Rita Marcangelo: I have always felt the necessity of sustaining the sector and going beyond the role of gallery director alone. The association was founded to create new opportunities for the development and qualification of the sector at an international level. One of the ultimate goals behind the association was that of creating a network of professionals who could achieve much more together than by working alone. This was all the more important in a country like Italy at the time, due to the fact that there was a total lack of “infrastructures” inherent to contemporary jewelry, that is to say academies or universities dedicated to contemporary jewelry, museums showing this kind of art, and of course a national association bringing together those working in the field. A lot has changed in this last decade, but there is still a lot to do.

I have always felt it my duty as someone operating in the field to contribute to its development in every way possible, and forming the association seemed an important choice, one that went hand in hand with what I was already doing. To this day, although I am no longer on the board, I am involved in the organization as curator of the AGC-Cominelli Permanent Collection and other projects.

My motto has always been “l’unione fa la forza” which I guess in English would be “united we stand, divided we fall.”

Whilst engaged with the Italian scene at a local level, you also resolutely positioned the gallery within an international circuit. I believe you were the first Italian jewelry gallery at Collect (2006): What was your gamble … and did it pay off in the long run?

Rita Marcangelo: We were indeed the first Italian gallery taking part in Collect as far back as 2006, and continued to take part for six years. This was another big challenge, since, compared to other international galleries who have access to financial support for taking part in events of this kind, to partly or totally finance their participation, no funding at all is provided in Italy.

In terms of results, through taking part in the event, we gained international recognition from the public and this obviously led to making sales during the fair to many collectors who may never have come into contact with our gallery otherwise, but also to further sales made through a new clientele (many people who had seen us at Collect later visited the gallery in Rome and purchased there). It also gave us the opportunity to sell to museums and private collections, which is always nice for the artists as it helps their careers. I would say that taking part in events such as Collect is important for any gallery wanting to reach out to a wider public, one that is made up of a qualified audience.

In 2013, your lease was up on via d’Ascanio, and you moved to larger premises in the city center. You were basically giving yourself a chance to start again … with 16 years of experience as gallery director in the bag. Did you set yourself a different mission than the first time around? Did you approach the setup of the new gallery differently than the first?

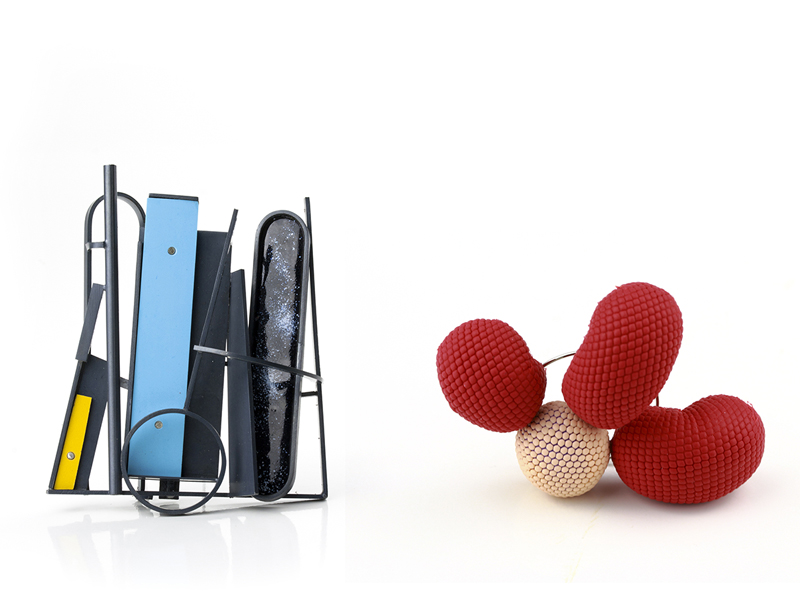

Rita Marcangelo: The move to new premises, although quite close to where we were before, has undoubtedly brought many new clients. We are based in a very lively area and we are very happy with the move. The gallery intentionally looks and “feels” the same as it always has, because we wanted to keep our identity. Our mission has also remained unchanged. It is still that of bringing contemporary jewelry awareness and appreciation to a wider public, one made up not only of collectors, but also of people who are approaching this type of jewelry for the first time. The focus is on an innovative approach on behalf of the artists expressed in diverse ways, characterized by the use of a wide spectrum of materials from paper to gold, along with a vast array of different skills, challenging the very notion of what is precious and pushing the boundaries of what can be considered jewelry.

Your roster of artists is now quite a bit larger than it originally was: You still work with some of your “historical” artists—Nagano, Franzin, Bloomard, Syvänova—who have been joined by a number of new faces. Tell us about that evolution: Do you choose makers differently now than you did when you began? How has the field—and I mean both artists and collectors—changed in the meantime?

Rita Marcangelo: We are approaching 20 years with the gallery now and I suppose it is natural that after so many years, we have a few more artists than we did in the very beginning, although our selection criteria has not changed. We take into consideration the quality of the artist’s work, how coherent their work is, innovation, and individuality. We try to find a balance between pieces that are wearable and thus more suitable for people who are actually looking for something they can use, and pieces that are less wearable and probably more appropriate for collectors. We like to be able to represent the many faces of contemporary jewelry, from the more conceptual one-off pieces to more design-oriented limited-edition pieces. The keyword, however, no matter what type of jewelry we select, remains quality.

Since we began, we have seen quite a change in the field as far as collectors are concerned, in terms of numbers. We feel there is a lack of “new blood” or young collectors to support the sector. From a broader prospective, I would say that society at large has also changed, meaning that the approach to possessing objects in general has become more oriented toward the temporary rather than something that should last a lifetime, and hence the very notion of jewelry, let alone contemporary jewelry, has become less important.

The last question I want to ask—one that I am most anxious to hear about—concerns the no-gram venture. To put it very simply—a and I hope you’ll correct me if I oversimplify—no-gram is a platform that sells unique and limited-edition contemporary jewelry online. You also have a return policy whereby you’ll ship work to collectors, who can send it back to you if they decide it is not for them. You and your partner Andrea Lombardo took four years to set up the website. Everyone I speak to describes the challenge of selling contemporary jewelry online as insurmountable, and yet you have succeeded. What was your original goal, and the challenges you thought you would face? What did you not anticipate, and how is it working now?

Rita Marcangelo: Yes, as you may have gathered, I like a challenge! It has indeed been a lot of work and it is like having another three galleries to run! Selling contemporary jewelry online is certainly not an easy task. As most people will say, they have to try it on, touch it, see how it looks, but I guess it can be compared to the sale of clothes or shoes online. It’s obvious that we are talking about a niche of people who may be interested, but the concept is that a “global niche” can be quite a large market.

We believe that if the world doesn’t go toward contemporary jewelry, it must be contemporary jewelry that reaches out to the world. The no-gram dream is that of being able to bring this type of jewelry to the most remote place in the world, to places where contemporary jewelry is unheard of, to people who cannot travel to find objects like these.

Another fact we took into consideration when setting up no-gram is a radical change in the market since we opened in 1997. Twenty years ago, if you wanted to buy this kind of jewelry, you would either have to go to a gallery, a fair, or maybe to the artist him/herself. In the last decade, all this has changed. We are faced with customers now being able to buy jewelry online from the artists’ websites, or even from other websites selling their jewelry. It’s what we call globalization! It is a sign that times have changed, and no-gram is our answer to these changes, to what the market is today. Of course, it may not be the only answer, but only time will tell.

One of the problems with working on the Internet is the infinite choice available that determines an annihilation of any differences, because everything is put on the same level. It is therefore more and more difficult for those who are unfamiliar with this type of jewelry to discern between what is of quality and what is not. In response to this, the works we propose are the result of a rigorous selection process, made through the careful evaluation of the quality of the pieces offered.

Another problem we didn’t anticipate was the difficulty in getting the artists involved in working in this new scenario. Working on a platform like ours involves different types of expertise, from providing photos, videos, etc. I think this probably has to do with the fact that our generation was not “Internet born.” Maybe the younger artists will be more prone to this change.

I lied. I have another question. You’ve done brick and mortar. You’ve done fairs. You’ve done digital. What is next, do you think, for Alternatives and for the contemporary jewelry market at large?

Rita Marcangelo: We will be working to consolidate no-gram and discovering new ways of communicating this art. Ultimately, I personally would like to continue with my commitment to the jewelry sector and contribute to its further growth in any way possible.