For Panjapol Kulpapangkorn, building community, working with memory, and getting to know people from distant places through his participatory project, Jewellery Is at My Feet/The Show Is Yours, has been a fantastic experience. An exhibition of some of the works from the first four years of this enterprise is on show at ATTA Gallery. Taking contemporary jewelry out to the broader community is one of the aims of this potentially far-reaching and ongoing project.

Vicki Mason: You majored in jewelry in an industrial design context before completing a jewelry MA in the UK. How have both courses influenced or informed your jewelry practice?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: I am interested in how I can communicate my ideas to people and how to provide something that I believe in to society. “Thinking process,” “communication process,” and “production process” are what I retained in both courses.

Can you talk us through the genesis for the project and exhibition Jewellery Is at My Feet?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: Jewellery Is at My Feet/The Show Is Yours was launched in 2012 when I lived in Birmingham, UK. In that time, I started asking myself, “What is jewelry?” I spent almost one year figuring out the meaning and definition of jewelry for me, by traveling: from one place to another, one footstep after another, to open up my perspective. I documented my journey by collecting found objects, writing a diary, and filming some valued moments. All these things had a strong relationship to me. When I looked back at things I collected, it felt like I was wearing these memories with me all the time: not on my body, but in my mind.

A memory is precious, personal, and individual. In my view, a memory can be defined as a piece of jewelry that is still with me and a part of me all the time.

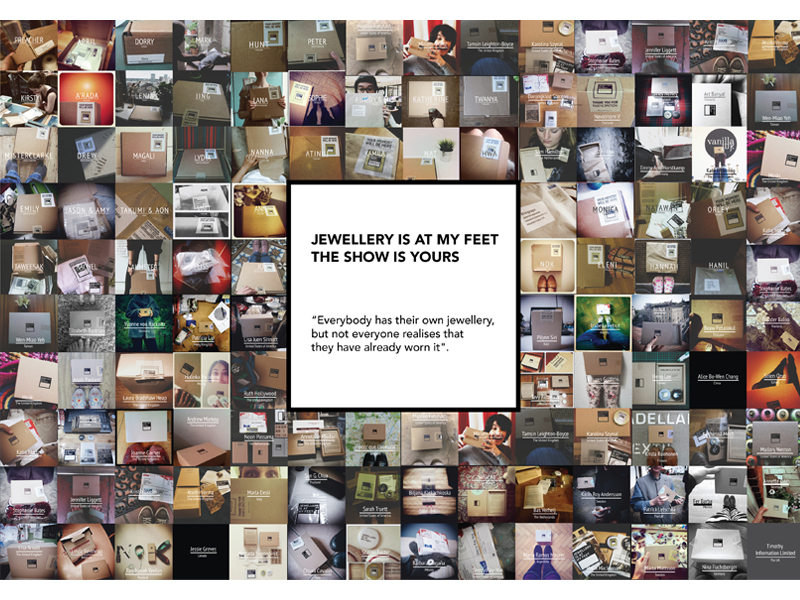

And I believe that everybody has their own jewelry, too. So I created this campaign—“Everybody has their own jewelry, but not everyone realises that they have already worn it”—as a way to communicate this idea to other people. Over two years, 133 participants from 25 countries participated in this project by sending me their precious memories: memory objects with stories attached to them, and films of valued moments. This became my main material for creating a “piece of memory” based on each participant’s story.

The project has been five years in the making. Could you please outline some of the logistics? For example, how participants were selected, what they were asked to do, what they were to send to you, what happens to the finished works, etc.?

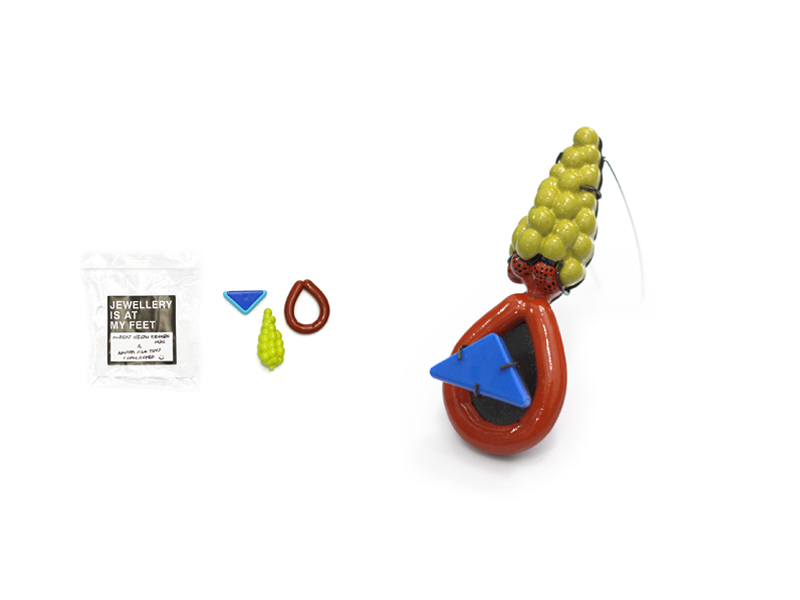

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: I had no rule for selecting people: My main goal was to disseminate this idea into society. Prospective participants email me, introducing themselves and asking to join the project. The one thing that they have to do is “find their own jewelry and figure out what their memory looks like” by recording their own valued moment, collecting memory objects in a clear plastic bag, and writing a short diary-like description of what they collected on a clear plastic bag.

“Train ticket to island,” “wrapping paper for my sister,” “the first ring I bought for my girlfriend,” “my dog’s hair,” and even more, were sent to me. Each one of these things is a piece of jewelry, which they have already worn in their mind. After I get this material, I attempt to create work by using the material from each bag as a main part and story.

I received 90 memory bags and, for this current exhibition, I made 41 wearable memory objects from the contents of 38 participants’ bags. Finished works were shown to the owner of each bag, so I could get feedback from the owners. These works will not be returned or sold, but will be made into a postcard for each individual owner.

For this current exhibition, I put 10 “memory kits” up for sale. Visitors can buy them, collect their memories, then return them to me. I will create two pieces of memory from each bag I get: One piece will be sent back to the owner and another one will belong to the project.

What sort of criteria did you employ to sift through and select whose bags to use, and then what to use and what not to use from each bag?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: Actually, I don’t have a pattern for choosing which bag I am going to work on. When I receive a bag, I always look at its content carefully, take pictures, write notes about the story it retraces, watch the film, and read what is written on the bag. I try to connect together the fragments in the bag, one by one. And then it depends whose bag gives me an idea first: when I have it, I start creating.

How did you assign titles to the works? Were you responding to the text on the bag or the objects you were presented with, or did the titles come out of your own reading of what was sent? Can you tell us for example, about My Piece Is in the Museum of Plastic on Sunday, from 2016?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: It is quite the same as making pieces. I had a rough idea the first time I looked at her memory and films about her traveling around, collecting used toys from a market and going to the museum. That story—when I received it—did not have a name: That was for me to piece together.

The works have the characteristics of bricolage art, where readymade everyday objects, junk, and so forth are often used to comment on ideas about “value” and the disposable nature of society and culture. Are improvisation and DIY approaches to making and exploring notions of value important to you?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: Yes, you could say that. I really love to work with readymade everyday objects because they carry stories from their previous owners. Every piece has an individual story. And even if it is a plastic cap, it will be different in its details.

This project challenged me when I started making pieces from participants’ memories. It felt as if I was a part of those memories but I had to find my own way to communicate their story, using their memory objects as a raw material.

Another important aspect of the project is its participatory element: This, too, has a powerful ideological aspect. Is it what you reference in your memory kit as “a new approach to jewellery”—and in the exhibition title as “the show is yours”? What do you think the participants’ expectations are regarding the project? Why do you think they accepted your invitation to participate?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: It is a community project and all participants are a part of it. This project’s aim is to share my perspective of jewelry with others who believe, like me, that their memories can be recast as a piece of jewelry and who decide to be a part of the project. The title, The Show Is Yours, tries to communicate that the exhibition is not created by me: I am just a sender, sending messages to others.

The caption of each work refers to the “giver’s” name. Do you think a potential buyer and wearer of these works will be open to tapping into another person’s memory of the place, space, time that these jewels now reference?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: The main focus of this project is not on prospective buyers, but on the community. Its purpose is to share experiences and to search for a new way to communicate a sense of what contemporary jewelry can be, to people who have no idea what it is. I am just happy with sharing ideas and memories, and gathering together people from different fields.

Memory plays a vital role in your work. How has it been working with other people’s memories? What have they opened up for you, if anything? What do they mean to you? Have you learned anything from delving into the grab bag of memories others have furnished you with?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: It was fantastic. I got to know a lot of people through this project. Sharing ideas and experiences with others is always great. I learned a lot from people and always got inspired by our conversations. If I cannot understand someone’s story, I always email, Facebook, or even phone them to talk about it. All the bits and pieces they provided carry a strong personal story. It was really great to be able to learn so many things and to develop work using memories of people from all around the world.

Do you have other participatory projects in mind for the future, or is another iteration of this project a possibility? Do you, for example, intend to track the future of these objects as they gather more memories?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: I continue working on this project. I regularly receive requests for participation—and some of the participants are still in the process of collecting their stuff. So I think it will be a long-term project.

Did you collect your own memories and make your own Jewellery at My Feet jewel(s)?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: Yes. Recording my own journey, before launching the project, I collected almost 100 bags in my studio. And in 2012, I created a collection of white wearable objects, on the surface of which I projected films. That was my first collection of jewelry … and then, before I started this project, I made one piece called Your Eyes Never Sleep, Smile from one of my personal memory bags.

What is your first memory of a jewel or jewelry?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: My first memory about jewelry happened when I was a kid. My grandmother was a jewelry shop owner. There were a few makers in her shop, who worked on traditional gold jewelry. I can remember that one day I saw the bench and I really loved it and an old man did something with fire to connect pieces of gold together: That was a kind of magic! I think this memory is one of many reasons why I love working in the field of jewelry.

What is the price range for the works in the exhibition?

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn: None of the finished pieces are for sale. The only thing for sale in the exhibition is a box—the “memory kit.” You can buy it for $290, collect your own precious memories in it, and return it to me. Within one month, I will create a piece of memory from it.

Panjapol Kulpapangkorn, Jewellery Is at My Feet/The Show Is Yours, 2012–2016, film, participants filming their own valued moments, photo: artist

INDEX IMAGE: Panjapol Kulpapangkorn, Jewellery Is at My Feet/The Show Is Yours community project, launched in 2012, memory objects, mixed media, photo: artist