Susan Cummins: Where were you born? And where do you live now? What is your house and studio like?

Susan Cummins: Where were you born? And where do you live now? What is your house and studio like?

Monika Brugger: I come from the Black Forest, near the Swiss border in Germany. After a lot of moving, I finally settled in Little Brittany, France, in the countryside, with a garden, vegetables and flowers right outside of the window. My studio is now in a small town between Rennes and Saint Malo, and still under construction.

Can you describe the step-by-step process that led to your show in Thailand at ATTA Gallery?

Monika Brugger: A long time ago, I had a student from Thailand, and she spoke to the gallery about me. I was very happy about their invitation to do this exhibition, and it was easy to work with them. Of course it also gives me the possibility of visiting a new country and to have contact with jewelers from other cultures.

![[left] Monika Brugger, Wound, Gift of the Seamstress, detail, linen, garnets, ± 200 mm, photo © Corinne Janier [right] Monika Brugger, Needle, gold, silk, 40 mm (needle), photo: artist [left] Monika Brugger, Wound, Gift of the Seamstress, detail, linen, garnets, ± 200 mm, photo © Corinne Janier [right] Monika Brugger, Needle, gold, silk, 40 mm (needle), photo: artist](/sites/default/files/aint_monica_brugger_4_5_600x800px.jpg) What were you thinking about as you put together the work in Damage Control?

What were you thinking about as you put together the work in Damage Control?

Monika Brugger: I wanted to show new works and some of the key elements related to them. Finding a title for an exhibition is always the most difficult part for me. I want it to tempt, to indicate a vision, to open up approaches and points of view on questions of the jewel and its relationship to objects. So in this case, when I looked at all the selected works, I saw that they related to a text written by Caroline Broadhead in 2008 entitled Damage Control. So that is how the title was found.

Can you walk us through the ideas behind one of the pieces included in the show?

Monika Brugger: In my work I have different “departure points,” often not really calculated. In the case of the “thimble” earrings, it started with the fact that a lot of people have seen one of my first rings (Fingerhut), a thimble, this very feminine tool, not very fancy, a small and usually completely forgotten utensil worn on the tip of the middle finger. So I appropriated the real one for these new pieces. But now they are no longer hidden in the sewing kit but shown and hung around the face. Another set of earrings was also inspired by some very lovely earrings from the 19th century. Humor is a very important aspect in this series. They are jewels with a surrealist aspect, with a wink to what can happen. The red garnets are present and allude to the damage we do to the ears when we make the hole to wear them.

![[left] Monika Brugger, Fingerhut, ring, gold, silver, 20 mm diameter, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [right] Monika Brugger, A Thimble!, earrings, aluminum, red gold, garnets, ± 50 mm, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [left] Monika Brugger, Fingerhut, ring, gold, silver, 20 mm diameter, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [right] Monika Brugger, A Thimble!, earrings, aluminum, red gold, garnets, ± 50 mm, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris](/sites/default/files/aint_monica_brugger_14_15_600x800px.jpg)

Are the ideas of memory and damage intertwined?

Monika Brugger: I can only say yes given the way you ask the question. Many pieces are made using the idea of “memory,” or they refer to something I said, I learned, or I need to deal with. Making brooches is not only about making beautiful compositions with different materials and forms, but it is also the fact that you make an object that is related to the human body. This will affect how the wearer is perceived by the viewer and by society. When I use a garment and when I sew the elements directly on the textile, I speak, among other things about the memory of a sorrowful period of my “national background.” I also refer to jewels as a mark on the body, and to all the ways societies invent reasons to include or exclude a part of the human race by force or voluntarily. This is human damage.

What interests you about absence?

What interests you about absence?

Monika Brugger: In his analysis of Parcours, Christian Alandete said it best: “And yet it’s very much within the world of jewelry that Monika finds her place. This is the basis of her self-understanding, whatever form her work may take—a photograph, a piece of embroidery, a book, a projection. She has a paradoxical capacity to make jewelry manifest via its very absence.” In fact I don’t usually make traditional jewelry. It is absent.

Why is your jewelry largely made up of cloth and clothing?

Monika Brugger: Everything has to do with coincidence. I was invited to the artist-in-residence in Bienne and didn’t bring all my tools with me. At the same time, I was occupied by the question of the interaction between brooches and garments and thinking about the relationship between the object and its support. A brooch can’t exist without the clothes. So it was possible to explore my interest about the result of “a thing” on the body and not about the “thing.” My intention was not to provide a decorative object designed to be placed on clothes but to set out to contaminate fabric with shapes and patterns. It provided an association so that the final piece could be considered a sculpture, a jewel, or a dress. I tried to make the brooch as abstract as possible, revealing its associated functions as a vehicle for personal identity, underlining social and ritual roles while questioning society as a whole. It could depict a body-borne stigmata, corporatist markings, private signs, or work-induced scars.

Monika Brugger: Everything has to do with coincidence. I was invited to the artist-in-residence in Bienne and didn’t bring all my tools with me. At the same time, I was occupied by the question of the interaction between brooches and garments and thinking about the relationship between the object and its support. A brooch can’t exist without the clothes. So it was possible to explore my interest about the result of “a thing” on the body and not about the “thing.” My intention was not to provide a decorative object designed to be placed on clothes but to set out to contaminate fabric with shapes and patterns. It provided an association so that the final piece could be considered a sculpture, a jewel, or a dress. I tried to make the brooch as abstract as possible, revealing its associated functions as a vehicle for personal identity, underlining social and ritual roles while questioning society as a whole. It could depict a body-borne stigmata, corporatist markings, private signs, or work-induced scars.

In several installations, clothes are metaphors of the body keeping the public gaze at a distance. It is also a fact, discussed by Georg Simmel, that clothes and jewels are the artifacts we use to construct our social body. But jewelry has a longer life. Clothes will be damaged faster. They are deformed by the body and marked by usage. Clothes will depreciate faster than jewelry and go out of fashion immediately. I like to talk about the contradiction of values between an object of contemplation and an object of use.

How did you become interested in making jewelry with these materials? What is your background in making?

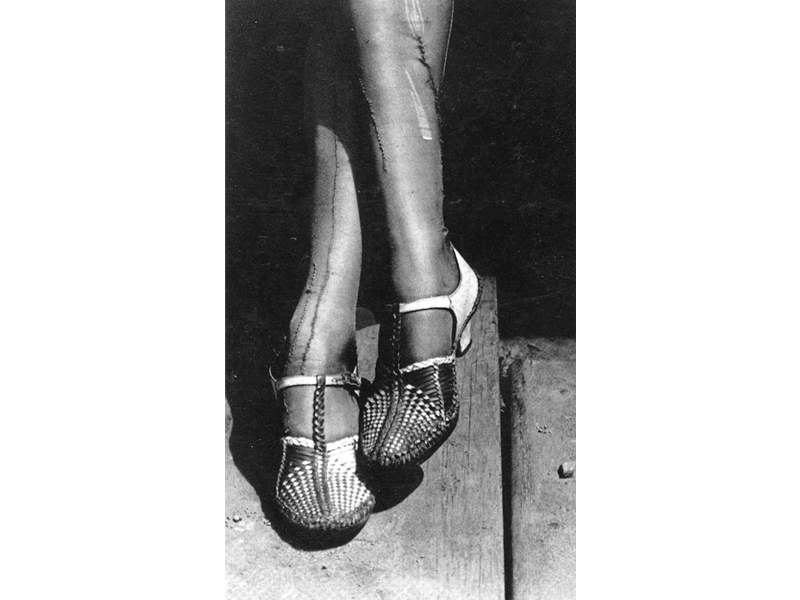

Monika Brugger: It is never the material I’m interested in; it is the concept of the project that determines the materialization of my ideas. I’m inspired by stories and images like the photograph by Dorothea Lange called Mended Stockings, from 1934, or the novel The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other marks on fabric worn on the human body. It is the interaction between a brooch and the support that are the focus.

Monika Brugger: It is never the material I’m interested in; it is the concept of the project that determines the materialization of my ideas. I’m inspired by stories and images like the photograph by Dorothea Lange called Mended Stockings, from 1934, or the novel The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other marks on fabric worn on the human body. It is the interaction between a brooch and the support that are the focus.

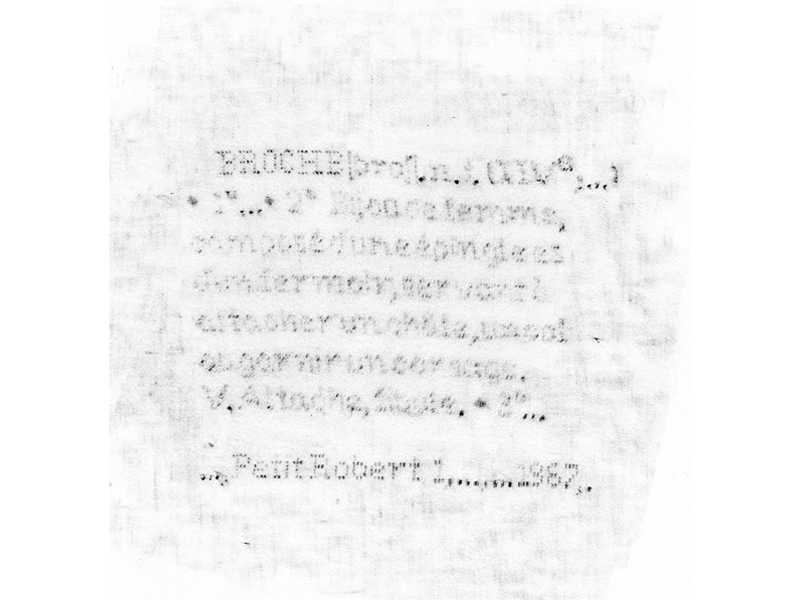

All young Nordic girls of my generation had to learn to use techniques such as hand sewing, embroidery, and other traditional handicrafts. In the piece Inseparable, I have stitched the definition of “brooch” from my favorite French dictionary, called Le Petit Robert, into the cloth. Robert is not only the name for my favorite dictionary, it is also an old French slang word for a woman’s breast. Using these outdated feminine techniques to embroider the image of a brooch is also for me a way to deal humorously with very serious themes, and to make a conceptual work in the most applied way. Using textile and cross-stitching is my way of being “in between” different approaches and contexts, crossing over the traditional approach of making jewelry.

I learned sewing in school, I make my own wardrobe, I like fabrics and the feeling they provoke. I use clothing because it speaks about the whole. It has movement, a silhouette, and a reference to the human as a whole. Jewels are the details. They need a place to exist. They have this extraordinary quality “to assist” or to perfect the beauty, the attractiveness, and perhaps the illusions that wearers and makers want to create. I’m always attracted by images depicting “la couture” or the representation of female archetypes and other tricks to make someone look beautiful. But it is the project that gives me the opportunity to explore uncommon and common materials.

I learned sewing in school, I make my own wardrobe, I like fabrics and the feeling they provoke. I use clothing because it speaks about the whole. It has movement, a silhouette, and a reference to the human as a whole. Jewels are the details. They need a place to exist. They have this extraordinary quality “to assist” or to perfect the beauty, the attractiveness, and perhaps the illusions that wearers and makers want to create. I’m always attracted by images depicting “la couture” or the representation of female archetypes and other tricks to make someone look beautiful. But it is the project that gives me the opportunity to explore uncommon and common materials.

But I’m not the first one to explore this very special field between fashion and jewelry. Emmy van Leersum and Gijs Bakker did it in the late 1960s, and it was a beautiful surprise to read the gijs+emmy spectacle from 2014. It turns out we have both developed projects around similar questions and we used comparable materials to connect jewels and clothes together in an original way.

The German word schmücken has its etymological origin in “sich in ein kleit smücken,” which can be translated as “bejeweled in a cloth.”

I think that it is also necessary to understand my work in a French context. There was not really a contemporary jewelry movement when I started in the 90s. Jewelry was identified by the “haute joaillerie” or the fashion jewelry/custom jewelry industry. We had few schools, and less support from the national institutions or museums. So in a way France was a kind of “no man’s land.” This gave me the possibility of exploring different approaches and the possibility to find answers to the questions in a proper way. I know that it was this environment that gave me the right atmosphere to explore, to progress, to make, to ask questions, and that introduced this kind of approach, which is connected with the fashion industry, “la mode” and the vision of femininity in France.

I think that it is also necessary to understand my work in a French context. There was not really a contemporary jewelry movement when I started in the 90s. Jewelry was identified by the “haute joaillerie” or the fashion jewelry/custom jewelry industry. We had few schools, and less support from the national institutions or museums. So in a way France was a kind of “no man’s land.” This gave me the possibility of exploring different approaches and the possibility to find answers to the questions in a proper way. I know that it was this environment that gave me the right atmosphere to explore, to progress, to make, to ask questions, and that introduced this kind of approach, which is connected with the fashion industry, “la mode” and the vision of femininity in France.

You often use red thread in your work. What does the color red mean to you?

Monika Brugger: Using red thread makes sense!

Red as blood, white as snow, black as hair, or “How I wish that I had a daughter that had skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood, and hair as black as ebony” (Snow White). The reference is not as easy or direct, but if you make works in textile, the fact is that you can get hurt and bloodstains might follow. This fact and also this real experience give me the possibility to explore these new elements and forge new ways of making ornaments.

The first time I used the red thread was in Passage, part of the series called Parcours. I made this monogrammed embroidery out of cross-stitches, like a bloodstain, in reference to lost virginity. All the pieces included garnets and always referred to working traces, wounds, and injuries, like the piece Stichwunde, Geschenk der Näherin/Wound, Gift of the Seamstress.

What does red mean to me? Well, red is most powerful in a symbolic way. Life and death are united in it.

In French, the expression “C’est cousu de fil blanc” means very predictable, flimsy, or “la supercherie est vite découverte.” It is “Fadenscheinig” in German, but simply too obvious in English or American, I think. But I sew with red thread. As well we can find an echo in the expression “un fil rouge”—a red thread or common thread—which gives coherence to an ill-assorted group!

Who are your muses?

Monika Brugger: Muses? Artists by example, by their works, and their radicalism have opened up for me a kind of possibility to do the same. you need to bring in all your energy. Artists from the jewelry field who inspire me are Onno Boekhoudt, his work as well as who he was as a person, the work by Manfred Nisslmüller, and Otto Künzli. Also the works of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Mona Hatoum have given me a kind of confidence to continue. But in the end, gardening can be a very good muse for understanding the world and for confronting essential things.

What have you read, seen, or heard lately that you could recommend?

Monika Brugger: I can recommend the documentary film Le Testament d’Alexander McQueen, by Loïc Prigent, a film about the creations and the background of Alexander McQueen. Also, I have taken the book by Winfried Menninghaus, called Das Versprechen der Schönheit (The Promise of Beauty), once more out of my library to reflect once more on this very complex and complete book about beauty and what it promises.

Thank you.