Manon van Kouswijk has much to celebrate. Her exhibition In Order of Appearance has just opened at Amsterdam’s Galerie Ra, and her book, Findings (written by AJF editor Benjamin Lignel), has just been published. Van Kouswijk shares her thoughts on the fine arts of making, teaching, and living in this new interview with AJF.

Marthe Le Van: Where were you born, where do you live now, and where did you study jewelry?

Manon van Kouswijk: I was born in Warnsveld, a small town in the east of the Netherlands quite close to Arnhem. Later, I studied jewelry in the Netherlands. I did a very technical goldsmithing and silversmithing course in Schoonhoven, and, after that, I went to art school at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, where I had to pretty much unlearn everything they taught me in Schoonhoven! I moved from the Netherlands to Australia a number of years ago and now live in Melbourne.

You were the head of the jewelry department at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie from 2007–2010. What was your teaching philosophy? What is an example of a project you gave the students that you thought was very effective?

Manon van Kouswijk: I view teaching as creating a space for students where they can explore what they want their work to be, while offering them a framework in which they can study and develop their own approach and working methods, preferably guided by a group of lecturers that present them with different views. Throughout that process, my personal tastes and preferences shouldn’t be too dominant. In Amsterdam, we once did a project that was called “The Material World,” in which students were asked to develop their ideas in working through this big subject; the outcomes were really quite diverse and very interesting.

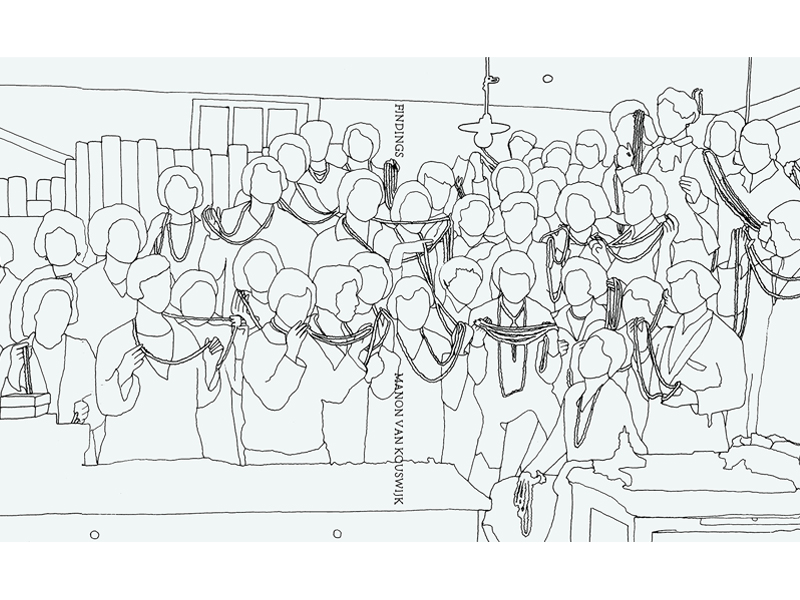

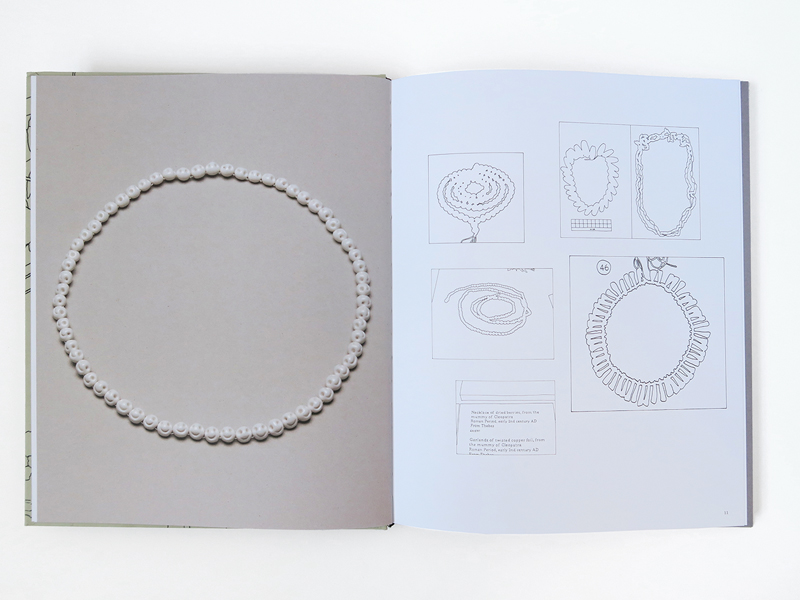

Line drawings and jewelry are given equal presence in Findings. Please describe your intentions for how these different art forms relate to each other on the page and in your creative practice.

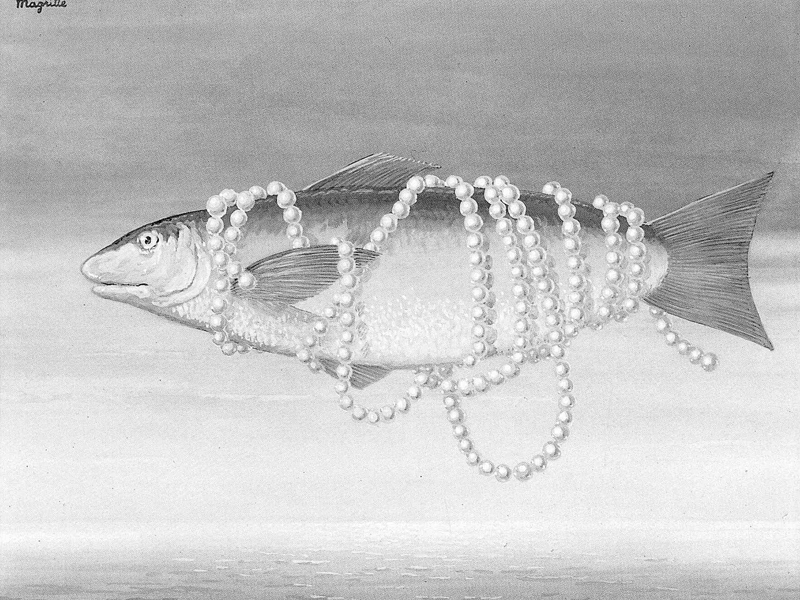

Manon van Kouswijk: I have always collected jewelry-related images as an extension of my practice. In the publication Findings, the drawings trace the broader context that jewelry operates within, the “world of jewelry,” whilst the images of my works are pretty much without context (objects “floating” on colored backgrounds).

The works that form part of the book are all based on different ways of materializing negative space (between my fingers, in a mold, etc.). I felt that the process of tracing the images somehow complemented that making process as it creates negative space in the images.

The objects and drawings work like positives and negatives: There’s a dialogue between the content of the work and the drawings.

I’ve chosen to make the book this way because I know from previous experience with making books that there’s a broad audience out there that has an interest in well-made publications, and I like the idea that my books can also be of interest to people outside of “planet jewelry.”

At Galerie Ra, I use some of the drawings from the book and also a series of drawings that I’ve made especially for the exhibition as a device that connects the different works in the exhibition.

What makes clay your medium of choice for jewelry?

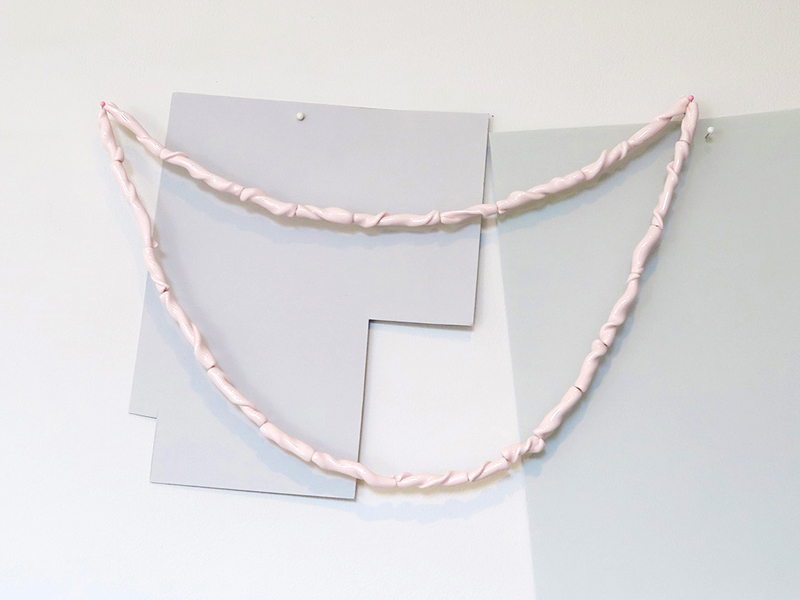

Manon van Kouswijk: I have worked with lots of different materials before I started to use clay, so I wouldn’t say that clay is my medium of choice for jewelry. (For example, more recently I did a work that is a series of 100 necklaces made of the plastic sheathing from paperclips.) But it’s true that I have been increasingly working with porcelain since undertaking a residency at the European Ceramic Workcentre in the Netherlands in 2002. The material allows me to reproduce existing jewelry forms as well as design and shape my own forms by hand. In addition, it can also mimic other materials, all of which interests me. Many of my works echo archetypal jewelry forms and motifs in different ways, and working with porcelain clay still offers me a lot of possibilities in exploring this area.

Could you describe some of the rules you apply to your bead-making process?

Manon van Kouswijk: Most of my works evolve from a process of developing ideas through experimentation with material and form, trying to discover something in the process that interests me and has the potential to become a work. Until that happens there are no rules, there’s just a large amount of trialing, searching, and thinking (and a lot of stuff that ends up in the bin). Some of my works are methodical. I did a series of necklaces based on making shapes with two, four, six, eight, and 10 fingers, so in this case, the method of making defined the resulting shapes.

Multiples seem to occur throughout your work—multiple beads on necklaces, multiple necklaces in a series. What do you find appealing about repetition?

Manon van Kouswijk: The jewelry archetypes that I use as a starting point for my work, like the beaded necklace, are usually not unique singular pieces. They are generic; they can be found pretty much everywhere and have their own specific appearance in different cultures.

The omnipresence of something that looks pretty much the same or is based on the same principle wherever it is made is something that appeals to me. It makes sense to me that my translations/interpretations of these archetypes are not unique pieces, either, but that they exist in series. I also use variations within these series as a working method, and constellations of forms that are individual but also belong to a group of objects.

How do you choose your color palette and surface finish, and how do these choices impact your forms?

Manon van Kouswijk: I think it is usually the other way around; ideas and forms are developed first, and then I think about how the choice of color might impact the reading of the work. I have always used a lot of white, which is, for me, a kind of departure point, an empty space, something that is not (yet) entirely defined. A white form is like a model that can be reimagined in any color.

In using color, I often work with the associations that some colors evoke in combination with particular forms. For example, some of my white necklace forms seem to mimic teeth and bone. The same shapes made in other colors resemble materials like crystal or glass. Made in pink clay they appear corporeal.

Each brooch seems unique in shape, like a snowflake, and seems to have infinite structural potential. Is this a series you plan to continue?

Manon van Kouswijk: I’m not sure right now. I have worked on this particular series for several years and have moved on for the moment. But I do often revisit work and sometimes there are years in between before this occurs, so who knows. I might come back to this process and develop it further at some stage.

Has your relocation from Europe to Australia had any direct effect on the artwork you produce?

Manon van Kouswijk: I was afraid you might ask that tricky question! And of course I would love to tell you exactly what moving country has meant to my work, but I’m not sure that I can. Would I have made the same works had I stayed in the Netherlands?

I think it’s a really good thing if you are forced, from time to time, to relate to new surroundings and different circumstances where you can’t take things for granted. This experience can be quite unsettling as well. I actually think my work has helped me to find my place in Australia, because it has been one of the few constants within all the changes that came with this big move.

You have continued your teaching career in Australia. Do you have any reflections on the difference of skills or attitude between the students in Amsterdam and Melbourne?

Manon van Kouswijk: It’s hard to say if students are different here, as I think students tend to respond to what is offered and to the context they study in. I do think the professional and educational context for contemporary jewelry is very different in Australia than in the Netherlands. It has a different genesis, and jewelry in Australia is taught in universities, which creates very different circumstances for studying than the European art schools. I think the way in which jewelry is taught here is still quite segregated from other visual practices. At the Rietveld Academie, jewelry is taught in a way that integrates other areas of visual art and design practice much more, and I think jewelry students in Amsterdam are also challenged more to articulate a strong position within their work, not just through making but also through thinking.

Have you recently experienced anything that filled your mind with wonder or your heart with joy? What was it?

Manon van Kouswijk: A trip to Myanmar last year, a dip in the ocean at Cape Patterson, a biography of John Cage, and two beautiful publications on the collections of Harry Smith: “paper airplanes” and “string figures.” As you see, I can’t choose!

Thank you.