Susan Cummins: Robert, tell us how you came to make the film J. Fred Woell: An American Vision. Please explain the title.

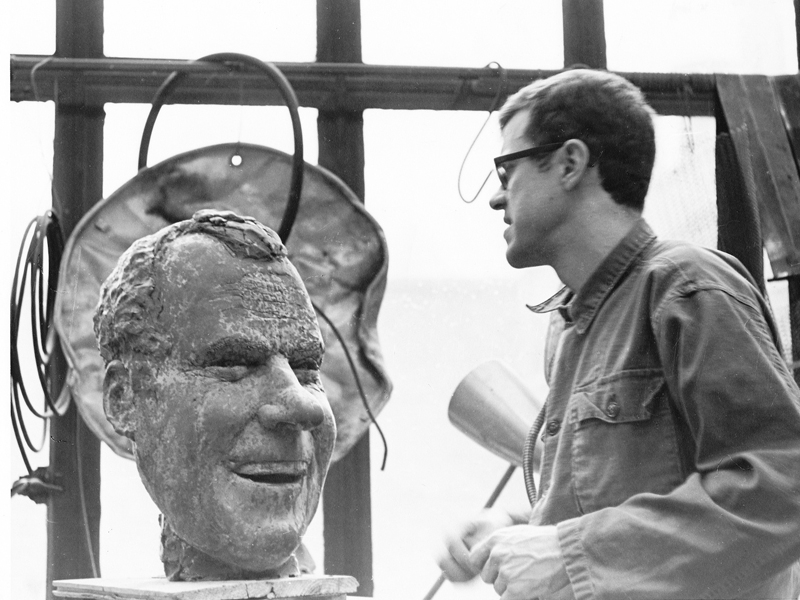

Robert Shetterly: I didn’t choose the title, but I think it’s a good one. The title is wide open for interpretation, but I choose to see it politically. Fred’s work seeks to understand and comment on the political and moral history of this country. It’s his vision as a single American coming to terms with his country. It’s a vision that attempts to be clear eyed, avoid denial and patriotic amnesia. I helped to found the Maine Masters Project of the Union of Maine Visual Artists in 1998.The idea was to produce documentaries about excellent Maine artists we felt were overlooked. Fred had been on that list for a long time. Most of the others have been painters and sculptors. It was time to recognize a craftsperson whose work transcended craft.

You have a role in the film, along with Fred’s two wives and several of his former students and jewelry peers like Eleanor Moty, but you have a different connection to Fred. Could you please say a little about your background and your relationship with Fred? When did you meet him?

Robert Shetterly: I’ve been an artist in the same Maine country as Fred for many years. I’m the head of a state-wide artists union and had asked Fred in the past to give talks about his work at the union meetings. I can’t say when I first met him, but more than 30 years ago.

I had known Fred slightly for a long time. And known about him longer. We were practically neighbors but had never been close. I was an admirer. As much as his art, I was familiar with his politics—his letters to the editor, his sharp political wit.

Your reflections on Fred’s work are especially riveting. You describe his well-known pin, Come Alive, as subversive. Can you explain why?

Robert Shetterly: Any time you can produce an artwork and get another person, perhaps an unsuspecting person, to wear your opinion, that’s subversive. But everything about it is subversive. The big Pepsi smile, the wire at the top in the shape of a military helmet, the dangling, decorative bullet casings to punctuate the “Come Alive” smile. In other words, Fred is using the happy slogan to take the mask off capitalist exploitation—the marketing of an unhealthy product as pro-life, pro-joy. In its dark heart is the impulse of imperialism—profit first, people last. That Fred can get all that into this little piece of jewelry is remarkable. And any time you can make a political point like this and get people to smile at it, it’s doubly subversive.

Would you describe all of Fred’s jewelry as subversive? What does it take to make something small and seemingly decorative like jewelry into a culturally or politically potent object? Why was Fred so good at doing this?

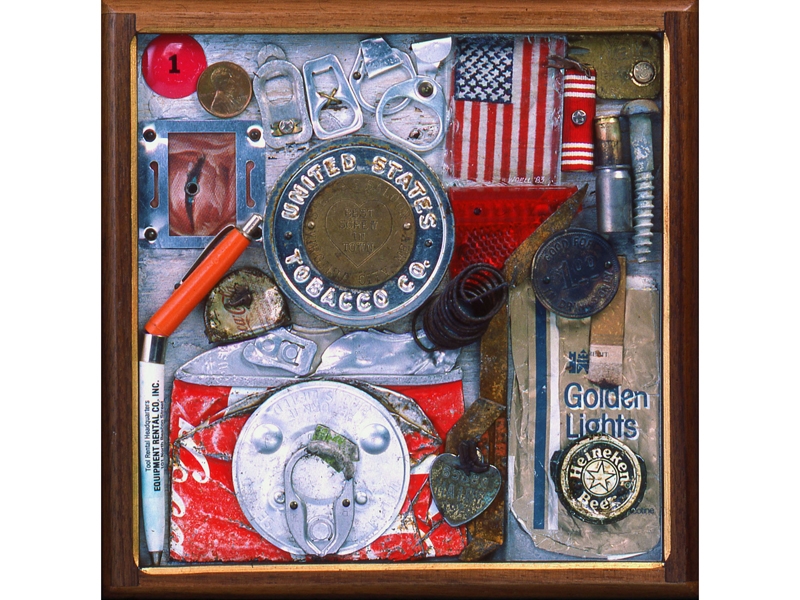

Robert Shetterly: No, not all of his work is either subversive or political. He used his medium to express the full range of his humanity and personal history. Fred was exceptionally aware of the latent cultural metaphors in the seemingly unimportant product artifacts we use and throw away. What made his work leap to another level was that he could combine meaning with aesthetics. Being able to do that is a rare talent—a kind of imaginative wit, to make beauty potent. To make each piece a poem, an essay about history and culture. Why was Fred good at doing this? I don’t know—some curious, simultaneous combination of passionate involvement and ironic distance.

How does Fred’s use of language in his poignant and witty titles augment his work?

Robert Shetterly: Fred’s language and titles extend the humor of his art. They’re both direct and tangential. The words often open other avenues to meaning that most of us wouldn’t see, i.e., they make reference to ideas more abstract than the art. His titles play with the art like Goya’s titles play with the etchings of the Caprichos. Fred’s words are like mice that jump on a sleeping cat.

What kinds of political actions did Fred engage in? Did you know him in the 1960s when he was first developing his style and his political interests? What was he engaged with then? Did he listen to NPR or read liberal newspapers or books? Do you know the sources for his views? Did he join protest marches? Can you tell us something about his letters to the editor?

Robert Shetterly: I didn’t know him as an activist except for his letters and I think we took part in some of the same demonstrations. But I didn’t know him well then. His letters explain the political anger that appears in his art as wit. That is, the letters directly attacked injustice and hypocrisy. Ironically, I think it’s fair to suggest that a person who might wear one of his social commentary brooches—admiring its cleverness—might have no patience for his letters. I read him in the Ellsworth American. I think he also wrote letters to the Bangor Daily News and the Blue Hill Weekly Packet and the Island Ad-Vantages.

The treatment of Native Americans is a regular theme in Fred’s work. When did he become interested in this issue, and why did he think it was so important?

Robert Shetterly: I don’t know when Fred first began to make work concerning Native Americans. For a person like Fred, who was always asking what’s really going on, what truth is propaganda hiding, exploring the treatment of indigenous people was only natural. So much denial there, so much inverting of the truth—as in branding them, the victims, as the “savages.” A culture is best understood by investigating what it is hiding, how it attempts to celebrate its greatest crimes as virtue. Fred had a very keen sense for dissecting hypocrisy. And, more importantly, until one exposes and faces these things, they will never change. The propaganda is taught to each successive generation.

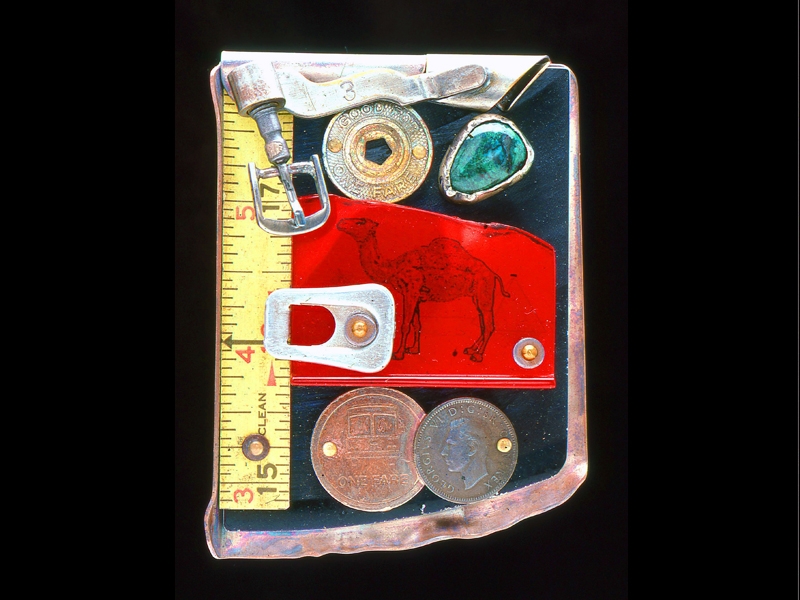

Is there a particularly American political statement in Fred’s use of found objects in his work? Why did he start using them instead of the usual precious metals and gems?

Robert Shetterly: Fred had a loathing for false value. That is, make it with gold and it’s worth more. The value has to be in the art, or there isn’t any. Precious metals and gems were (are) the extension of political and economic hypocrisy into the art and craft worlds.

What effect did Maine have on Fred’s work and his views of the world? Why did he choose to live in this part of the world?

Robert Shetterly: I never talked to Fred about this. But I suspect because Maine is in many respects an authentic place. Spare and incredibly beautiful, a place where an artist can feel aesthetically grounded enough to produce authentic work—not work that mirrors the environment but work that attacks the forces which undercut and diminish authenticity.

You run a website called Americans Who Tell the Truth. Do you think Fred belongs on this website? What truths do you think he most wanted to tell in his jewelry?

Robert Shetterly: Fred could certainly be a portrait on my website. I’ve painted many other artists whose political or activist work I admire. I think Fred most wanted to show how US imperialism and militarism is omnipresent, can be seen in a bottle cap, a flip top, a strand of barbed wire, a seemingly innocuous coin. More importantly, he wanted to display, have us all wear, his outrage at systemic hypocrisy, and practice compassion for the victims.

The film J. Fred Woell: An American Vision is available for purchase and can be scheduled for a showing. Would you give our readers contact information?

Robert Shetterly: The film will be shown at the Museum of Arts and Design on March 29 at 6:30. The event will include a panel, moderated by Barbara Gifford, with Richard Kane, Paul Smith, Glenn Adamson, and Helen Drutt.

To book a screening, find out about other showings, or inquire about future availability of DVD and video on demand, please contact us through our website: https://www.jfredwoell

Thanks so much.