Miriam Mirna Korolkovas is a force of nature. She has been a driving power of Brazilian artistic jewelry for decades. She started as a visual, body, and musical artist who used jewelry as one of her main forms of expression. In the 1980s, she opened one of the first schools in São Paulo. She exerted herself as a devoted teacher and mentor, sharing her knowledge of the intricacies of art jewelry, extending the boundaries of the Brazilian production, and bringing the community of jewelry artists together. Lately, and in addition to her other roles, she has served as a prominent curator of national and international exhibitions. These have already joined the history of contemporary jewelry in the country. I talked to Korolkovas about her extensive career, her plans, and her thoughts on the Brazilian art jewelry scene. Our conversations took place right after the closing (in June 2022) of the sixth exhibition of the REFLECTION series, which took place at A Casa – Museu do Objeto Brasileiro, in São Paulo.

Ana Passos: Miriam, how do you feel after another successful exhibition, one that brought together 36 Brazilian jewelry artists from various regions and backgrounds?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: First, I have to explain the curatorial direction in this edition. I wanted to bring together people who have solid thinking and great experience with those who are just starting out and make very promising works. They are pioneers, like Reny Golcman, the honoree of this edition with a retrospective of six decades of work. Or researchers, like the young Raquel Amin, who worked with me to curate the exhibition.

I wanted to put the references and the future side by side. It’s not a matter of age or precedence, but of relationship with the jewelry universe. I also tried not to repeat names that already participated in previous exhibitions. After all, there have been six exhibitions since 2011. Like new shoots on a large tree, jewelry has a new breath. The growth is exponential and at the same time slow and fast.

I’m delighted with the result! There is more representation. The audience is growing.

As a researcher, I’m always curious about what makes a person become a jewelry maker. What is the oldest memory you have of a piece of jewelry? I would go even further: Can you establish the circumstance in which your relationship with jewelry began?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: My earliest memory is when my cousin and I played with a kit of plastic bits and pieces, making necklaces and bracelets, probably at age five or six. My relationship with jewelry starts with the gifts I used to receive from my grandmother, of Hungarian Romani origin, and my mother. Jewelry is important among the Romani. I always got a gold piece on special occasions. They were bought from a German lady who sold jewelry door to door. I remember with sadness a chunky pearl ring that I lost when I was young, left on the sink counter of a restaurant.

You are a dancer and a musician, too. Did your experience and knowledge of body expression determine your approach to jewelry? Did your interest in contemporary jewelry come from there?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: My jewelry has color, movement, and sound. My relationship with the body determines my approach. The jewelry is worn by us. Its support is the body in motion. Necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and anklets benefit from the movement.

There is another aspect to this issue. As an immigrant of European origin, in childhood I felt uncomfortable, different. I had to build a way of being in the world, of integrating myself. Perhaps that’s why I’ve always been interested in various aspects of Brazilian culture. There are so many influences. They all have a special relationship with the body. For example, the adornments of native peoples usually make noises when the body moves. An unparalleled colorfulness is another characteristic. My jewelry is the result of all this.

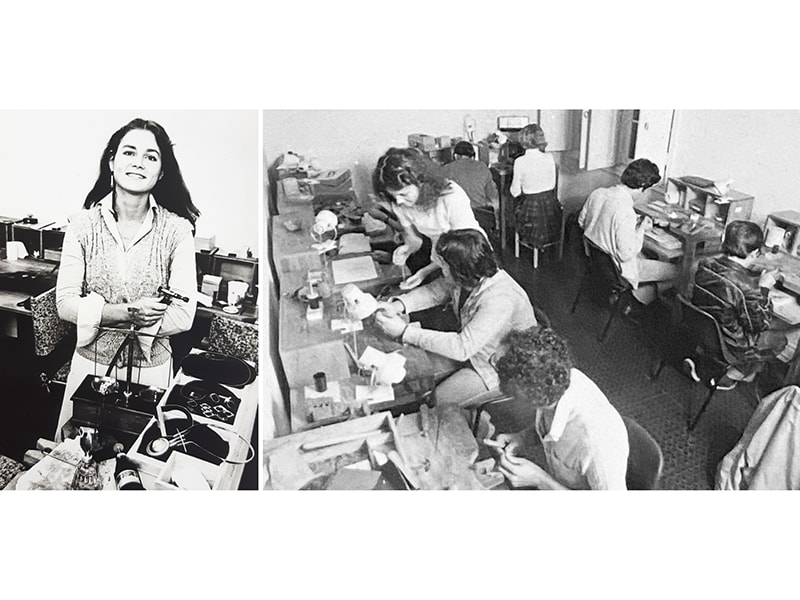

In 1982, you’ve founded Oficina Escola de Joalheria, one of the first schools of art jewelry in São Paulo. What was your motivation?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: I had been teaching in the backyard of my parents’ house for a long time. It was simple. There was a great demand and I decided to formalize this aspect of my professional life. The school was set up based on the metal studios I attended during my high school years in the US and the architecture art labs at university. Artistic jewelry flourished in Brazil. There was great interest. I had 100 students enrolled at one point.

(reproduction), photos courtesy of Miriam Mirna Korolkovas

What led you to study architecture and urban planning at university? How did that formal education contribute to your identity as a jewelry artist?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: All my family used to draw and paint. I had an artistic education from the beginning. It was a natural choice. As a second-generation immigrant, I had to have a formal career. I fell in love with geometry, the three-dimensionality of solid forms. My pieces of jewelry began to show a greater concern with the occupation of space and the quality of construction. They started to have volume and sharpness of thought and execution.

You carried out your master’s studies in the US, your PhD studies in Brazil, and your post-doc studies again in the US. What were the themes of your research? Were they reflected in your jewelry practice?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: Colored refractory metals and the influence of native peoples’ adornment production. Solid geometry. The five Platonic solids.

It was an evolution that is visible in two moments. In 2002, I presented the research Object Seed: Poetic Essays with Measure, Proportion, Harmony, and Rhythm. In 2009, it was the time for Seed: An Architectural Study for a Shelter. Both are reflected in the shapes and volumes of jewelry produced since then.

You once wrote that you considered yourself a blacksmith. What was your experience with metals? Do you still work with those materials?

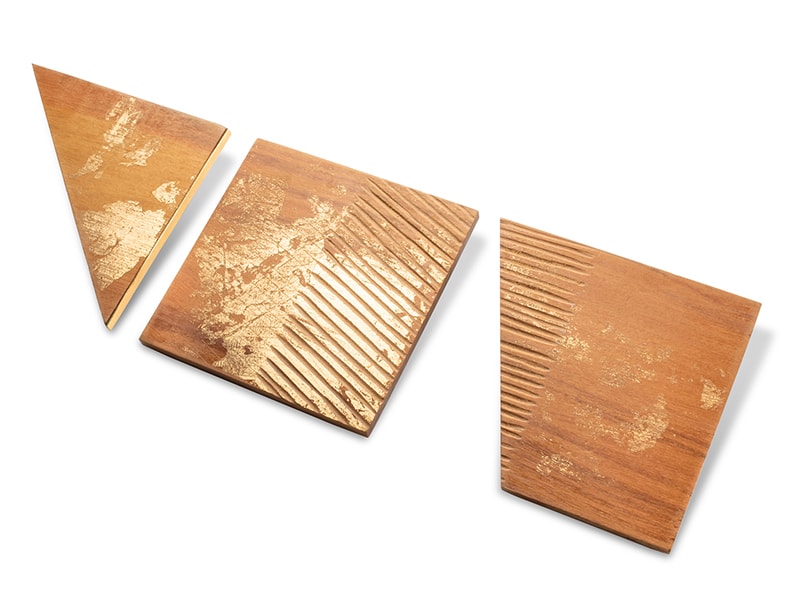

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: Since I was a teenager, I’ve worked with multiple materials, but metals—all of them—have always been a predominant medium. I started with lost wax. I worked with silver, copper, brass, and gold. I worked a long time with metal engraving, sculpture, and anything related to metals. Then I specialized in anodized titanium, niobium, and tantalum.

Nowadays, I consider myself more of a carpenter, because of my work with reclaimed wood. The metals are still there, but only as a support.

You have had a great involvement with the cause of Indigenous and riparian populations in the Amazon for many years. How did that happen? Did anything from the jewelry universe permeate this relationship? Did this experience change your relationship with jewelry?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: It all started with an expedition organized by a group of researchers with different specializations. The objective was to get to know extractive reserves. (Note: These are state-owned areas intended for sustainable development through natural resource extraction activities carried out by local populations.) We’d expected to understand how the culture of ancestral extractive activities preserved the social structures and the environment. We also saw illegal logging, gold panning, and digging in the region. Witnessing all those large-scale predatory activities impacted us all forever.

Since then, my role as an activist has emerged in my artwork. I’ve been in the Amazon region on five occasions. I learned a lot about the native people’s way of thinking and working with seeds, wood, and natural fibers.

What are currently your main sources of inspiration, both as maker and as curator?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: Sustainability issues, my findings as an urban collector or urban miner, and the ascendancy of the new generation. My jewelry is my speech as an activist. My work as a curator is to establish a dialogue with the artists and to promote contemporary jewelry.

How would you describe the Brazilian scene in the 21st century?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: It is vibrant. Many new talents are emerging. However, it remains very concentrated in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais. Other regions struggle to increase their presence. We need more collective projects, exhibitions, and publications to improve our knowledge and its expression. Research and experimentation should be expanded and deepened. Our experience can be enriched by looking at our culture and history. Nowadays, it is still very oriented to the European tradition.

Based on your experience, what is the role of an art jewelry curator when it comes to much-needed audience growth and artist qualification?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: A curator mediates the exhibition experience at all its stages. The artist needs exposure. The public needs clarity. An artist draws growth from being with other artists, learning to present and defend their work, receiving critiques and negative responses, being invited to work with pre-established themes, exchanging knowledge and experiences with other artists and the public.

I also like to mix different artistic expressions because it is challenging and enriching. As for the audience, the exhibitions are a didactic way to introduce the fundamentals of art jewelry and to increase interest by offering high-quality pieces of jewelry.

I imagine you follow the contemporary jewelry scene around the world. In recent times, what has caught your attention the most?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: I really appreciate works that reflect cultural identities, that establish a relationship with ancestry and the land itself. Lately, I’ve seen works with that sensitivity in Finland, Chile, and Japan. Identity is key in understanding contemporaneity.

What would be your advice for those who want to pursue a career in contemporary jewelry?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: Study. The first step is to study history. Art history. And after that the history of jewelry, too. Research. Never stop researching. Tirelessly question your own practice. Get to know your own culture in depth. And, of course, build your own language based on profound knowledge of selected materials, tools, and techniques. It’s a kind of literacy process. It takes an inquisitive spirit that never stops investigating to become a good jewelry artist.

One last question. What would you like to see happen in art jewelry in the near future?

Miriam Mirna Korolkovas: I’d like to see more exchange and collaboration among artists. We need to respect different approaches and expressions. There is a lot of prejudice, which prevents us from exploring new possibilities. I’d like to see even more curiosity and interest about the land we live on and about our ancestry. We should reach broader audiences by truly representing ourselves. I hope I can see the young people take over. We nurture them and we must trust them.

Miriam, thank you so much for this conversation about your career and ideas, and for all the time we’ve spent together. I look forward to your next projects!