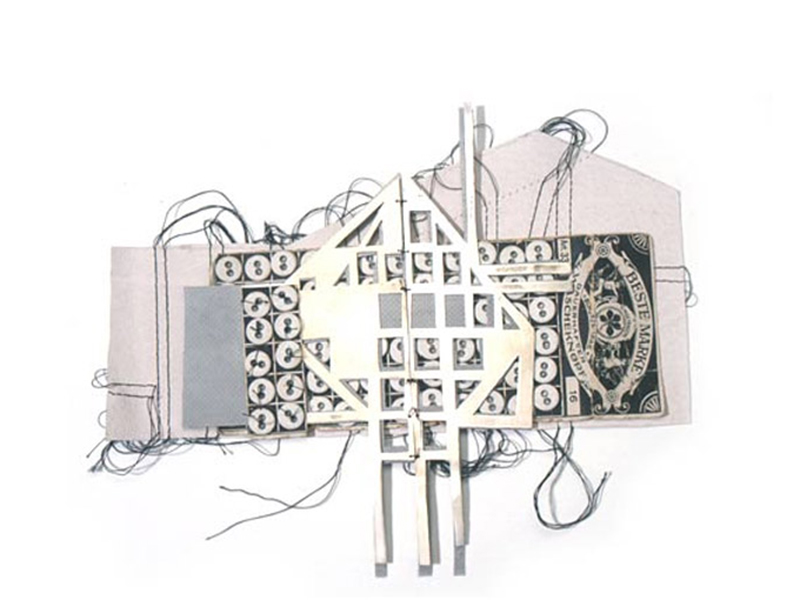

Last week, we announced that Iris Eichenberg had won the highly coveted 2021 Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant. The $20,000 cash grant will support Iris Eichenberg: Where Words Fail Me, a mid-career retrospective that will include some 40 works documenting Eichenberg’s development from her 1994 prize-winning graduation show at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie onward. The retrospective will be exhibited at the Museum of Craft and Design, in San Francisco next year, and will include key examples of jewelry, objects, and installations, alongside several new statements created specifically for this show. One of the jurors for the award, Emily Stoehrer, was kind enough to interview Eichenberg.

Emily Stoehrer: Congratulations on winning The Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant! How are you celebrating?

Iris Eichenberg: Slowly—realizing the impact, the consequences—and thankful to you all. This will stay with me for a long time, so the celebration takes place on so many levels.

With this grant you plan to mount an exhibition and publish a monograph. Can you tell us a bit about that project?

Iris Eichenberg: This show is the result of month-long visits with curator Davira Taragin to look into and at my past, selecting work and editing the choices again and again. Davira has offered a valuable, outside perspective, which does not have my maker-investment in the work, yet has taken me along, looking and seeing what I produced in the last three decades. Together, we searched for recurring themes and the bones of my work.

It was a thorough, meticulous process. What is finally going to be a selection of 45 works is a small percentage of all that I have made. It does, however, encapsulate the essence of my journey. I often work in a series and choosing one of these moments places a sense of responsibility and urgency on each piece.

As a whole, this show is a new and old body of work at the same time. The works call each other into being and exist in interdependency. These works have not been in conversation with each other, so there is a new, yet already-existing, sound which would have been, otherwise, unheard. I am excited. What came together allows me to learn from my work and allows me to share that experience with an audience. The catalog[1] will be a document of what a German/ Dutch/American maker produces and becomes at the turn of the 21st century.

What is your process like from the spark of an idea to a fully finished work?

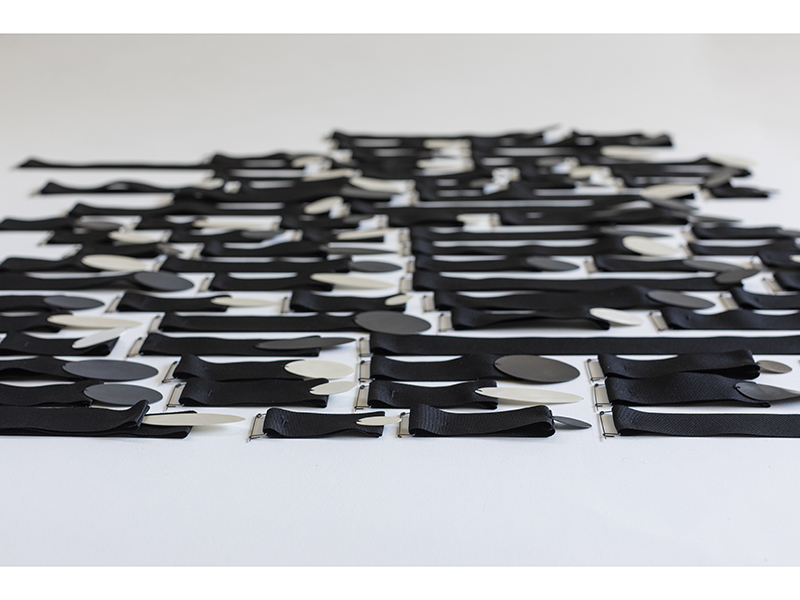

Iris Eichenberg: I stutter in material; desperation and helplessness manifest themselves in the attempt of covering (up) and layering—the repetitive visitation of a surface.

I draw comfort from ordinary things, and my aim is to share this comfort gained from seemingly mundane objects and shapes which I put through laborious material transformation. The comfort lies in the urgency given to a thing. The things which live with me have a life of their own. I put them through a process, but each step of the way is a moment of change and alteration. When I change those lives, my life changes as well.

Only I can see what happens. Only I can decide to stop or proceed. There is no efficiency or economic logic to my process; on the contrary, the only aim is to fathom out the everything of this nothingness. Process is often everything.

Objects which live with me chatter and have a sound, a voice, and, together, they vibrate.

I feed into this sound, not knowing where it goes. But I have a sense of tuning it by giving and taking from the material—nebulous and messy, private first, then personal. I then aim toward opening up space, yet never filling it.

How would you describe your jewelry?

Iris Eichenberg: I can’t. If I could, I would have fully understood. That will hopefully never happen.

Your early career was marked by winning the Gerritt RietveId prize in 1994 in the same way your mid-career is now highlighted by the Susan Beech Grant. Is this a moment of reflection for you?

Iris Eichenberg: I remember clearly that getting the Gerrit Rietveld prize fueled my courage to make uncompromised work. The knitted work I made for my graduation is still one of the most precious bodies of work to me; and being awarded for the work I care for is beautiful.

If receiving this award somehow marks the middle of what has been an extraordinarily successful career as an artist and educator, what do you hope to accomplish during the second act?

Iris Eichenberg: I tend to see where I failed or have been scared that I compromised my special pact with beauty. I often look at my work as sort of an other. I could not help myself to make. But especially, this curiosity to get to know the other in me and the work makes me work.

In the years to come, I hope to be at home with my work. I would love to be free of voices and expectations. I am constantly striving for fearless making.

You come from a European tradition but have spent the last decade teaching in the United States, at Cranbrook. What do you see as some of the differences (or similarities) between the jewelry field in Europe and in America?

I think we reached the point of healthy confusion. If I would or could answer this question, I would go for so many cliches, which would just make our experience smaller.

I am afraid my view changes constantly, and my taste plays tricks on me. I lost interest in works which inspired me in the past and learned to appreciate works I did not seem to notice before.

I used to identify myself as a Dutch artist, deeply entrenched in Dutch tradition; I thought I had a certain taste. Luckily, we do not need to sign a taste contract. Being uprooted and rooting again does not happen without pain but having the chance of becoming within and through different cultures and languages has been the biggest gift.

How has your job as head of the metalsmithing department at Cranbrook influenced your studio practice?

This teaching position spoils a person, due to the company of young people who, in the best-case scenario, grow beyond what can be imagined and take conversations further than my own horizon. As head of metalsmithing—and I would prefer to call it smithing, as we do not just smith metals—I am bedded in a wider discourse with colleagues at Cranbrook who teach and challenge me as well; in that sense, I am a lifelong student.

Although I would love to see for only a second the work I might have made had I stayed in Europe, here at Cranbrook—the surroundings, the sort of studio-proximity with students, the campus, the history in each nook and corner—I have, for sure, produced vastly different work. At times, it feels like time travel; often it feels far away from a former conversation, which gives me a certain freedom from a former self.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, this has been a usual year. How have you been spending your time?

I have been knitting red wool hearts during the pandemic. They are much larger than human hearts, revolving around the notions of belonging and loss. I filled the bird feeder often and watch the birds with my cats; I have a new understanding of loneliness; and I am fluent in talking with myself in three languages. I have had the chance to feel blessed with amazing friendships and colleagues.

I healed helplessness with the Hand Medal Project and felt a sense of completeness doing that with Jimena Ríos.[2]

I started walking at night, speculating about the lives of all the people in the big houses around here.

I made work, as that is my safe space and something nobody can take away, but I also had doubts about my role in the art world and the relevance of the power we grant it.

What advice do you have for those just starting out in the field, or those makers who are nearing their mid-career and looking for a way to mark this accomplishment?

Show up! Do not aim to arrive, but keep moving. Do not get corrupted, or at least try to fight it. Take your work seriously, but not so much yourself. You cannot do it alone.

[1] A 40-page, fully illustrated catalog with contributions from educator Ben Lignel, curator Davira Taragin, and JoAnn Edwards, the executive director of the Museum of Craft and Design, will accompany the retrospective.

[2] Learn more about the Hand Medal Project in the article In Your Hands.