Susan Cummins: Tell us about your background. Where did you grow up, and where did you study?

Petra Hölscher: Born in Recklinghausen, I am a child of the Ruhr district, which is located in the state of North-Rhine Westphalia. It’s a region of Germany that until the 1970s was known for coal mining and the steel industry. In addition to the characteristic workers’ housing estates covered in a coating of gray coal dust with their allotments and dovecots, the pit head shafts of the mines and their (now greened) coal dumps, it’s the soccer stadiums of Dortmund, Bochum, Leverkusen, or Gelsenkirchen that bring color to the look of this region. Arguably very few people think of the Ruhr district as being a place for the arts. Who knows, for example, that the Bauhaus artist Josef Albers was born in the city of Bottrop? It is located in the Ruhr region as well, as is the city of Essen, which is home to one of the most attractive opera houses of the 20th century and the brainchild of Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto.

My decision to study at the Christian-Albrechts University, in Kiel, took me to North Germany. People know Kiel as the venue for the Olympic sailing regattas of 1972. We tried to compensate for its location on the periphery of Germany, indeed the periphery of Europe, by going on excursions. One of these trips was to what was known then as Breslau and is today called Wrocław, with the “Jahrhunderthalle” (Centennial Hall) by Max Berg, the buildings of the 1929 Werkbund exhibition, the romantic islands on the Oder River, and artists circles around the authors Gerhard and Carl Hauptmann. How could anyone not be fascinated by this city? Later the “Breslauer Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe” (1791–1932)—with its famous figures such as the architects Hans Poelzig, August Endell, and Hans Scharoun, or the artists Alexander Kanoldt, Carlo Mense, Johannes Molzahn, Oskar and Kaska Schlemmer, Oskar Moll, and Georg Muche—became the topic of my doctoral thesis. Like many of over 100 German-language art schools around 1900, the Breslau Academy was every bit an equal to the Bauhaus of Walter Gropius, in Dessau. The only difference is that people forgot about it.

Could you talk about your role at the International Design Museum in Munich and your development as a curator?

Petra Hölscher: Before I came to Munich, I spent three years at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, in Dresden, in Saxony. Indeed, in 1998 many people were still interested in what was going in on the new states of a united Germany. In Dresden, I was one of the curatorial teams working on the large-scale special exhibitions Art Nouveau in Dresden for the Kunstgewerbemuseum (1999) and Eine gute Figur machen. Costume und Fest am Dresdner Hof zu Zeiten August des Starken, for the Kupferstich-Kabinett (2000, Museum of Prints and Drawings). The exhibitions were shown in the castle of Dresden, which at the time—not yet rid of all its war wounds—offered a truly special setting for the presentations.

Then, in 2001, I was invited to assist the Bayersiche Schlösser- und Seenverwaltung (Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces Gardens and Lakes) with the exhibition Pracht und Zeremoniell in the Munich Residenz. And there I was, all of a sudden, in the Bavarian capital, concerning myself with the architecture and furniture ideas of architect, designer, and artist Leo von Klenze. It is his majestic buildings that go toward making Munich look so special today, examples being the façade of the mansion on Max Josef Platz, or the opera, with its magnificent portico. In Munich, I happened to meet Florian Hufnagl (1948–2019), who was then the Director of Die Neue Sammlung. He had assisted us with loans for the Art Nouveau exhibition in Dresden. He shared my ideas of what a modern museum should be like: shaking up and breaking down the hierarchical divisions erected in the 17th century between art, architecture, and craftsmanship. His fascination with the art of indigenous peoples, his appreciation for the achievements of arts & crafts, his open mind when it came to the new and taking different approaches in connection with design intrigued me. His respectful handing of every single object, giving each one the space in the display case or on a pedestal that had previously been reserved solely for sculptures from the field of fine arts, made the presentation in the Pinakothek der Moderne in 2002 unique. Today, a good 20 years later, that’s standard practice in the field of design.

And what kinds of shows have you curated over your time in Munich? Only jewelry, or do you curate other media as well?

Petra Hölscher: Apart from being responsible for the permanent exhibition in Pinakothek der Moderne, Die Neue Sammlung covers some 24 collection areas and is responsible for the design section at Neues Museum für Kunst und Design in Nuremberg and in the International Ceramic Museum in Weiden.

So its range of collection areas extends far beyond the more classic fields like ceramics, metal, glass, furniture, and textiles: from the Paris metro station, by Hector Guimard, to Nymphenburg porcelain, by Konstantin Grcic; from the product photography of Gabriele Basilico to Afghan war rugs; from the blue-and-white packaging of Nivea cream tins to the Japanese lacquer works by Ettore Sottsass; from the American Willys Jeep (a genuine Willys Willys!) to the Danish bus shelter made of fiberglass-reinforced plastic by Poul Cadovius; from the AGIP service station that once stood on the old road up to the Brenner Pass between Austria and Italy to the necklace by Henry van de Velde donated by the widow of his generous patron and promoter Karl-Ernst Osthaus. There are many more items I could add.

My area of work developed out of my initial involvement with the organization of exhibitions. Over time I also developed the first presentations from works housed in our storerooms, such as Kubus und Keimling. Some 50 models of the toilet brush “Merdolino” (dear little shit), by Stefano Giovannoni for Alessi, stood on artificial turf. Right next to that stood the “Kompakt-Nasszelle,” by Werner Wirsing, a kind of prefabricated bathroom with washbasin, shower, toilet, and ashtray (!) molded in plastic. These models were fitted by the hundreds in the student village of the Olympic Games hosted by Munich in 1972. The presentation Hut Ab! showcased various design options for coat stands and cloakroom stands. With the exhibition Ron Arad—Designer, Architect, I focused on the broad range of Arad’s design work from the 1980s through the 2000s by presenting works for Rosenthal, Moroso, or Kartell on a shelf placed diagonally in the room. Green. Green. Green. addressed the great diversity and importance of the color green for industrial design. In the exhibition Spielerisch Sitzen, children’s chairs from a private Munich collection were arranged on whitened removal boxes, while the subject of the presentation Japan & Italy was the Asian-Italian liaison since the 1960s.

Some 60 televisions from our collection were arranged on Euro pallets in the exhibition TÉLÉVISION – 텔레비전수상기 – ТЕЛЕВИЗОР – FJERNSYNSAPPARAT – 电视机 – FERNSEHER; they related the history and development of the television set. Finally, the exhibition Korea: Design + Poster showed Korean objects from the collection areas of technology, ceramics, metal, mobile telephone, and jewelry. Every time I walk through one of our storerooms, ideas for exhibitions seem to pop out of nowhere.

Tell us about your first experience curating a jewelry exhibition. What challenges do you face in curating jewelry shows every year?

Petra Hölscher: Jewelry wasn’t really part of my brief here. For a long time, Dr. Ellen Maurer-Zilioli was responsible for the area of jewelry, but then she went solo as a gallery owner. She was followed by Dr. Sabine Roeckl. As long as Florian Hufnagl was director of Die Neue Sammlung, he was also the one who took care of setting up the jewelry collection, both in the museum itself and in the Danner Foundation. Jewelry was the work of the director.

My debut, if you will, in the field of jewelry came about through my involvement with organizing exhibitions: In 2009, I accompanied Dorothea Prühl to Stuttgart. We were on the lookout for the right cardboard on which she wanted to present her works in the exhibition Dorothea Prühl—Necklaces in our museum. It takes more than two hours to drive to Stuttgart … and then the same back. It was a really nice journey. But afterward I was very aware that if, as planned, I was to take over the organization of the jewelry exhibition, every jewelry artist would assume that I’m familiar with studio jewelry. Even though I had read such relevant publications as those by Ralph Turner, Peter Dorner, Fritz Falk, Curt Heigl, Gerhard Bott, Reinhold Reiling, and Peter Skubic, it was still a challenge to familiarize myself with the history of international studio jewelry.

What helped me was the fact that Claus Bury not only donated his jewelry sketches to Die Neue Sammlung but also his entire “jewelry correspondence.” That effectively launched the creation of an archive on the topic of studio jewelry. Shortly afterward, Peter Skubic gave us his extensive archive and drawing material. And Hermann Jünger’s family transferred parts of the his estate to us, which is now being catalogued and documented in the form of a PhD project by Nadine Becker. Klaus Zahn, the brother of jewelry artist Helga Zahn, not only enabled the Danner Foundation to acquire early works by his sister, but also bequeathed her written records, sketches, and working material to the museum. And together with loans from the family, this provided the material, in 2016, for the exhibition Helga Zahn. Schmuck. Unikat und Serie/Jewelry. One-Off and Series, accompanied by a publication.

In 2004, two years after the opening of the Danner Rotunda, the exhibition Hermann Jünger—Found Objects kicked off the series of large-scale monographic exhibitions under the glass dome of the Pinakothek der Moderne. The series is devoted to the founders of studio jewelry. Every exhibition catalog is conceived like a small mosaic stone that ultimately helps everyone better understand the history of studio jewelry. And the jewelry artists themselves are responsible for the look of the exhibitions in their honor. People are happy to use the black display cases by Jünger and his daughter, the interior designer Lene Jünger, which both came up with for his exhibition in 2006. Now and again exceptions are made to this rule, for example when the artists are unable to spend a longer period of time in Munich, as was the case with the exhibitions on Anton Cepka and Tone Vigeland. Incidentally, the exhibition about Cepka was the first one that I was solely in charge of and which many people claimed in advance would not succeed, as not enough of his works were known. In the end the opposite was true.

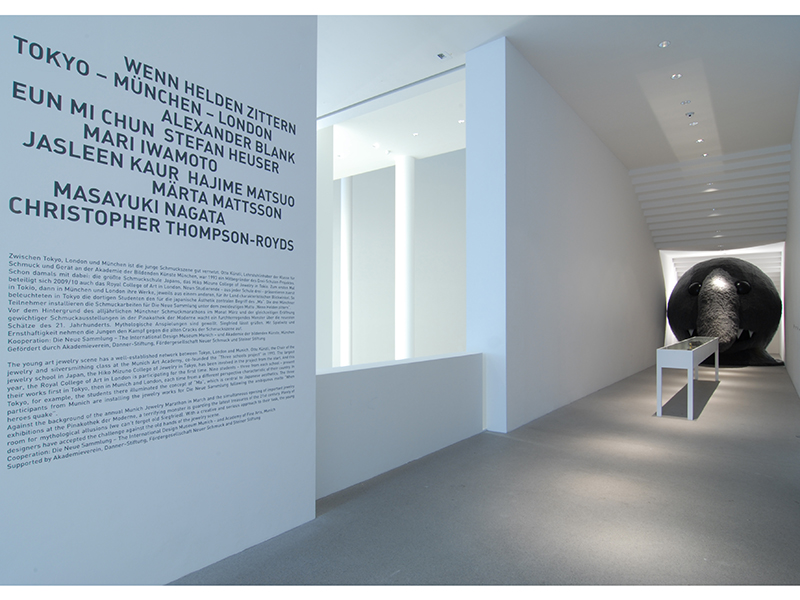

The series was joined in 2009 by the jewelry-class exhibitions under the stairs: no more and no less than a glimpse into the future and the potential stars. Professors and students joined forces to create the exhibition architecture for this awkward, tube-like space—whose very awkwardness constituted its charm. I feel the greatest respect for their ability to give this space beneath the staircase a fresh design again and again.

The City of New York shared my sentiments and in 2014 awarded a prize to the presentation Staring: In Hindsight, masterminded by a class at the State University of New York at New Paltz, led by teachers Jamie Bennett, Kerianne Quick, and Myra Mimlitsch-Gray. That was very gratifying for all of us.

Usually I’m the one to make the suggestions for all three formats—apart from the two formats mentioned, there’s our “Sunday Morning Lecture” during the Schmuck exhibition weekend. I’m guided by my own curiosity and my enthusiasm. I would simply like to find out more about the artists, who developed their own positions early on. To put it loosely, during the International Craft Fair, Munich simply brims over with exhibitions on contemporary jewelry artists, and at any rate the focus tends to be more on contemporary jewelry. That is fine! As a state institution, the museum has the means of reviewing an artist’s oeuvre and his position in the broader scheme of things. If things go well, there’s a publication and the findings of the review culminate in an exhibition. We try to exploit this opportunity.

What surprises we’ve had, say, when we discovered the very early works of Thomas Gentille, or exhibiting Tone Vigeland’s highly colorful enamel works, being able to hold the studded silver paper brooches of Peter Skubic, or finding out that the one or other brooch by Anton Cepka was inspired by his taking apart an old plastic sugar bowl coming out of his household. Never was the history of the Cold War so vivid for me than in reunited items featured in the jewelry symposium Jablonec ’68. If you quote Hermann Jünger at this point, then the symposium was the foundation for the strong international nature of studio jewelry from the start. And even though it might sound somewhat boring, ultimately the overriding interest has to be the concept of quality. Classifications such as indigenous peoples, gender naming, social status, training or the lack of it, likeability, age, and, and … in the end, none of these things should play a role. The sole criterion should be the quality of the object. And then if a rediscovery like that of Helga Zahn succeeds, or the guest curators of the Danner Rotunda select the beard jewelry of the Borana for an exhibition, then everyone is happy.

As I see it, the role of a museum is not to focus on exhibiting quantity, but quality. That might be different sometimes in industrial design, as in that instance greater numbers can also visualize function and serial production, making long text explanations unnecessary. Examples of that might be the stacking chairs or the variations of the kettle by Peter Behrens for AEG from 1908–1909 (!), which we exhibited in the Pinakothek der Moderne in 15 versions. How else could you visualize one of the first examples of intelligent industrial design? The modular platform method often jointly used by various manufacturers in the automobile industry is another case in point. Already in the Behrens kettles, the only differences are in the execution of the body—material, shape—while the base is always the same.

Apart from such considerations, not every item by an artist has to be shown or purchased, but this doesn’t apply to every good item. On the contrary. And I’m happy to put in the necessary effort: For the exhibition about Anton Cepka, I traveled over 14,000 km to collect the works for Munich … and that doesn’t include the return journey!

Owing to the quality of her works, but also because I was keen to find out more about her, the exhibition in March 2021 will be dedicated to jewelry artist Therese Hilbert and her work. Where does she come from, how did she start, and what development did she undergo in order to produce the works that we all love so much?

Do you also oversee the Danner Rotunda? Can you tell us the story of the collection? How often is the display changed? How do you choose the new curators each time?

Petra Hölscher: The history of the jewelry collection is very complex. There are actually two jewelry collections: that of the Therese and Benno Danner’sche Kunstgewerbestiftung, known as the Danner Foundation, and our own jewelry collection, that of Die Neue Sammlung.

The Danner Foundation has collected jewelry since the mid-1980s. At the end of the 90s, Florian Hufnagl decided to establish studio jewelry as a new collection area in Die Neue Sammlung. In 1999, the Danner Foundation officially made over its jewelry collection to the museum as a permanent loan. Since then we’ve taken on the task of cataloguing, conserving, and organizing the collection. In other words, both collections are relatively young when compared to the holdings of the jewelry museum in Pforzheim or the Goldschmiedehaus in Hanau.

The collections of the Danner Foundation and Die Neue Sammlung operate as a single entity: They respond to each other, complement each other, or address topics that would not perhaps be possible for the other collection. Today, one is no longer conceivable without the other. As you might imagine, this means it’s not always easy to relate the complex history in a couple of sentences. In the last two years I’ve looked at a lot of archive material and whenever possible conducted interviews with the authors—in other words, those people whose idea it was to collect jewelry. The outcome is the publication Schmuck—Jewelry, in German and English, jointly edited by the Danner Foundation and Die Neue Sammlung.[1] Consequently, for the first time most of the items of both jewelry collections are now available as images and it’s possible to read their history.

We’re delighted by the financial support we received to produce the book from the foundation Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung, which has close associations with the fine arts. This generous support helps to move studio jewelry away from its outsider role in the art world and toward being recognized in its own right as an art genre. The last time this succeeded was in the 1980s, when photography came into its own. Today, it’s an accepted part of the art canon. We hope studio jewelry will soon also become accepted in its own right.

In mid-2003, out of respect for his life’s work, Die Neue Sammlung invited Munich jewelry artist Hermann Jünger (1928–2006), who was already seriously ill, to curate the first presentation of the Danner Rotunda. Jünger asked Otto Künzli, his successor as professor of the jewelry class at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Visual Arts), to assist him. We celebrated the opening of the Danner Rotunda in March 2004 with more than 2,200 guests.

From the start, we decided to hold the presentation every five years. In 2009, the “young and unconventional” Karl Fritsch succeeded the “professor,” Jünger, and immersed the Danner Rotunda in the darkest chocolate brown. The tableaus were adorned with pastel-colored textiles. Fritsch favored a visual, painterly presentation over the individual display of objects, and requested loaned items from more than 60 jewelry artists. In 2014, Künzli returned the Danner Rotunda to its initial white and gray concrete look. More space was accorded to each individual object again. Out of respect for the efforts of his two predecessors, Künzli took especially attractive tableaus from their presentations and united them with his own ideas. This included new acquisitions and donations made in the last 10 years; he managed without any loans at all.

This generational change every five years has proved to be a valuable instrument over the long term. In 2019, after 15 years, it was time for a refurbishment. The reopening was scheduled to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Danner Foundation, in 2020. The display cases were redesigned and the lighting concept was also altered. Munich lighting designer Flavia Thumshirn switched everything over to LED technology, which is more flattering for displaying the objects. Since the switchover, the colors of the materials used in the objects, be they gold, silver, plastic or enamel, wood, glass, or ceramic, have a completely different glow. With Yang Liu Design, Berlin, neon lettering was developed to highlight the entrance to the Danner Rotunda, and a long-standing desire was finally realized. Moreover, Sabine Sense and her team from Bildwerk Art in Bamberg developed a virtual tour that allows visitors to the website to gain a first impression of what to expect.[2] None of this would have been possible without the many years of cooperation with the Danner Foundation.

Choosing a guest curator is not as easy as it might sound. Given its five-year cycle, the presentation almost assumes the status of a permanent exhibition, which isn’t to be underestimated. Often an idea that works well in a gallery or at a trade fair is unsuitable for presentation over a longer period. To put it loosely, it’s about the difference between a current hit and a classic item.

In 2020, for the first time we invited a team of curators to take charge of the new selection and presentation of the jewelry for the Danner Rotunda. In 2015 Japanese jewelry artist Mikiko Minewaki and Kagejama Kimiaki had jointly realized the exhibition Harebutai for Hiko Mizuno College, Tokyo, at the Pinakothek der Moderne. Everyone will probably remember the catwalk in the guise of a large red staircase on which the students’ works were presented. Simply brilliant! But Japan is not just around the corner. Telephone calls, emails, Skype, and WhatsApp are useful, but they also have their limits. And what they can’t replace is the actual work in space. Swiss-born Hans Stofer had moved from the Royal College in London to take up a professorship in Halle’s Burg Giebichenstein. In 2013, he and the class at the Royal College had solved the difficult task of not having an exhibition space owing to the closure of the Pinakothek. For the presentation Saplings 360°, the trees on the museum grounds in the direct vicinity of the temporary exhibition space Schaustelle constituted the venue. Minewaki and Stofer knew each other well, having already realized other exhibition projects together. What was more obvious than to ask Stofer whether he could imagine working with Minewaki on the new installation for the Danner Rotunda? We asked Munich-based Alexander Blank to take on what to my mind was the awkward, because it’s almost invisible, mounting of the works. During the installation phase he got on so well with the other two guest curators that they decided spontaneously to expand the duo to a threesome—a real stroke of luck for us.

The result is an exciting meeting of Asia and Europe. Once again the Danner Rotunda underwent a color transformation. This time the walls didn’t shine in a dark chocolate brown but in a bright blackberry red, cool pink, and a delicate off-white. For the first time, traditional jewelry objects by indigenous peoples from Africa and Asia claimed an equal place alongside modern jewelry works. The same is true for models by Francesco Pavan and Hermann Jünger. New acquisitions and donations from recent years alternate with objects from the collection holdings. New relationships and connections were sought that culminated in surprising combinations. And so for the fourth time a brilliant and highly individual presentation has been created in the Danner Rotunda. Naturally, you might wish and hope it is successful, but there is no guarantee that it will be.

Over the years, you’ve continued to add to the jewelry collection. What’s the process and criteria for acquiring a new piece? Do all the new acquisitions become part of the Danner collection?

Petra Hölscher: The Jewelry Acquisitions Committee at the Danner Foundation meets once a year. We’re lucky that every year the Foundation makes available a considerable sum for acquisitions. It’s up to the members of the Acquisition Committee to present artists and jewelry objects that they feel would be important for the collection. A decisive rule stipulates that those objects up for discussion must be viewed as originals.

Die Neue Sammlung does not have a jewelry budget of its own. Which is why we are all the more grateful when, in a charming, endearing, friendly, and ironic gesture, we receive support. Helen W. Drutt English started the ball rolling in 2006 when she gave us an object on the occasion of our jewelry matinee on Sunday morning. This has been repeated every year, and is not just any jewelry but generally the work of an American narrative (!) artist. Others—artists, collectors, gallery owners, colleagues, and friends—followed her example. With her considerate donation, Drutt established a new tradition in our museum. And we are incredibly grateful to her for having done so.

Can collectors donate their collections? Will you take the whole set, or only certain pieces?

Petra Hölscher: At the very beginning we received two very large donations: Peter Skubic made over 60 works from his private jewelry collection to mark his 60th birthday. It’s thanks to him that the focus was directed to artists from Eastern Europe (amongst others) and the jewelry scene there. One year later, Munich’s Galerie Spektrum donated over 80 works to the museum; they are largely by German, Dutch, and Swiss artists, which also represented a valuable addition. In both cases the collections were put together with a lot of thought for the museum’s own collection, which was still being established then.

Over the years and with the expansion of the jewelry collections of the Danner Foundation and Die Neue Sammlung, the situation has changed somewhat. It’s not easy for me to answer your question without appearing a little rude or arrogant. Perhaps I might make a comparison: We museum people operate like private collectors visiting a workshop or a studio. The jewelry objects are spread out on a table. There’s a certain tension in the air. You find your favorites. In the end, you decide on one, sometimes two items, or other times a group of several works. What I’m trying to say is that we all pick—we are all alike in that respect. Perhaps the questions that go through our heads are also similar once an item has attracted our attention. But sometimes a museum has to ask completely different questions, aware of its responsibility, the knowledge that it’s effectively writing history:

What position does the work occupy in the artist’s oeuvre, what place in the history of jewelry? What is the workmanship like? Is the object undamaged? How does the object fit in with the other pieces in the collection? Can it stand its own ground? Is it a “prima ballerina,” as I like to call items that want a display case all their own, or can you imagine arranging it next to other works—indeed does this item call for that? Does it need assistance from other objects? Does the work stand in a certain historical context?

It’s only through a very critical, one could say stringent, selection that the jewelry collection has become as strong as it’s perceived to be today. It’s this liberty in selecting items that accounts for the quality of the collection. And we need to preserve that liberty, even though this represents a considerable responsibility. And I myself would admit that this is easier to write on a sheet of paper than to implement.

Nonetheless it remains an emotionally difficult time for the other party, if a museum doesn’t wish to take on an entire collection. After all, there’s always a lot of passion involved. These are always very difficult moments when you have to reject someone’s generosity in this way. The discussions are not easy and the letters are not easily written. But ultimately it’s not about emotion, likeability, or taste, or even about me as a member of the museum staff. What’s called for are objective reasoning and classifications. It can’t be about personal taste or even personal preferences, but must be something larger: It’s about the jewelry collection and about strengthening it further, and not about leveling through larger numbers or abandoning previously selected standards. That’s where the difference lies from private collections. And I have to be aware of that as a museum staff member, as soon as I enter a gallery or engage in conversation with an artist. The museum staff member has to speak first, and only then perhaps the private person with personal jewelry preferences, something I’ve naturally also become in the meantime.

Can you talk about a few of your recent acquisitions? What distinguishes this collection from other museum collections in the world? What do you think are the most important or powerful pieces of jewelry in the collections? Name a few of your favorites.

Petra Hölscher: In 1995, Otto Künzli—alongside Hermann Jünger, one of the brains and thinkers involved in establishing both the Danner Foundation collection and the museum’s own jewelry collection—was asked by Florian Hufnagl to draw up a list of jewelry items that he felt were absolute musts for a high-quality jewelry collection. The purpose of the task was to ensure that the jewelry collection had the same quality as the other collection areas of Die Neue Sammlung. The list reads like a “Who’s Who” of the big hitters: Yasuki Hiramatsu, Margaret de Patta, Alexander Calder, Vivianna Torun Bülow-Hübe, Arline Fish, Tone Vigeland, Francesco Pavan, and Pol Bury. For the opening of the Danner Rotunda they were all represented by at least one object. Some other artists did not get their items shown until later, and with others we’re still waiting for the right item at the right moment, and that little bit of luck that’s always involved.

Only recently, two works by David Watkins, a pendant by Arnaldo Pomodoro, and a bracelet by Ed Wiener have been added to the collection of the Danner Foundation. Works by Onno Boekhoudt, Kiff Slemmons, Tone Vigeland, Kadri Mälk, Alexander Blank, Eunmi Chun, Bettina Dittelmann, Melanie Isverding, Hans Stofer, and Florian Weichsberger occupy important positions. Sometimes it has been possible to add an outstanding work to an oeuvre, thereby rounding it out. This was the case with the Große Fische (Big Fish) necklace, by Dorothea Prühl; the Nare pendant, by Otto Künzli; the works of Thomas Gentille; or the bracelet by E.R. Nele.

There is passion in almost every acquisition, and often the question of how it is to be managed financially. We recently had such a situation with a “pebble ring” by Naum Slutzky, dating from 1962. Normally, jewelry objects by Slutzky, who was once head of the Bauhaus goldsmiths workshop, are not to be found on the art market. Acting on his strong bond with them already during his lifetime, he donated his works to the Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Hamburg and later to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. When we heard that jewelry objects by Slutzky were on the market, we dropped everything we were doing, and spent the next two weeks gathering all the information that was available and conducting many phone calls and discussions. Various matters were to be settled: What position does the pebble ring occupy within our jewelry collection? What position within the international jewelry scene? And what position within the oeuvre of Naum Slutzky himself? Expert opinions were obtained, applications written, and then … Would we be able to gain the support of the potential financial backer? Thanks to Munich’s Paul and Kathrin Basiner Foundation, Slutzky’s “pebble ring” is a recent acquisition for the museum, as is also, incidentally, the jewelry collection of Kathrinn Basiner. It’s the first such collaboration with the Paul and Kathrin Basiner Foundation, and we very much appreciate their confidence in us. This is how you develop an intensive connection to objects in the collection. Hence it’s very difficult to name your absolute favorite.

What have you been reading or watching while you’re sheltering in place during the COVID-19 outbreak?

Petra Hölscher: Well, COVID-19 has made us aware of many different things—sadly, often mostly negative ones, and the virus has brought great suffering to people. I was very lucky that neither myself nor my family, friends, or acquaintances were affected or are affected by it.

Working from home and the slower pace of things meant I had the time to browse through jewelry books. And during this time, I also discovered the two books by the Korean Byung-Chul Han, who initially studied metallurgy in his home country and then philosophy in Germany. They’re called The Expulsion of the Other: Society, Perception and Communication Today and The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. I also read Beyond Thainess: Textil als Träger von Tradition und Identität, by Laura Linsig, for which she was recently awarded the Braun-Feldweg Award in Berlin.

Thanks so much for your answers.

Petra Hölscher: Susan, I’d like to thank you for your interesting questions. With Art Jewelry Forum you have created a brilliant communication platform for studio jewelry, which has meanwhile developed into much more than just a network or blog. The AJF events—whether they be trips, lectures, book publications, meetings, or so on—have become integral parts of life in the studio jewelry scene, and from which most of us, if I might say so, profit. Chapeaux! I doff my hat to this achievement!