Caroline Broadhead is a creative visionary who moves with ease across many disciplines, including jewelry, textiles, furniture, installations, and even collaborations with live performers. Her retrospective exhibition at CODA Museum in Apeldoorn, Netherlands, through April 15, 2018, showcases work that spans four decades and dives deep into the exploration of the human body and person. Awarded the Jerwood Prize for Applied Art: Textiles (1997) and winner of the Textiles International Open (2004), Broadhead is also the course leader of BA Jewellery Design at Central Saint Martins and lectures at institutions across the world.

Olivia Shih: The work you created in the 70s and 80s was innovative and shifted the way people perceived contemporary jewelry and its possibilities. What drew you to jewelry in the first place? What does jewelry mean to you?

Caroline Broadhead: I started making jewelry in a ceramic workshop at school, and I liked the fact that I could make something unusual to wear. I liked the small scale and the way you could change metal, coat it with enamel, solder it; it seemed a bit like magic. During an art foundation course I discovered that it was possible to study jewelry, which is what I went on to do. When I was there, metal didn’t hold my interest as much as I thought it might, and I used the time there to think and to play with other materials—plastic and wood. I also made things out of textiles when I was at home. It was after I left college that I started making work that I liked and got excited about. Jewelry is common to all cultures, so it means something quite fundamental. I really like jewelry’s closeness to a human being without actually being human.

One of your most recognizable works, Necklace/Veil (1982), is made from woven nylon and can be worn as a necklace or drawn up into an ethereal veil that plays with spatial expectations. What inspired this work?

Caroline Broadhead: This was made following a trip driving from London to Kenya and staying there for a few months. It was a few years after setting up a workshop, when I was trying to work out what direction I wanted to go in. I was bowled over by the jewelry I saw being worn by the Maasai and the Turkana people. Encountering jewelry playing a very different role firsthand was refreshing and expanded my ideas. Wearing larger-scale work in a unselfconscious way and where there was meaning attached to each and every piece was exciting.

When I returned to England, I realized I wanted to explore ideas freely rather than rely on earning an income from what I made. Getting a part-time teaching job allowed me to feel more confident about making bolder pieces. I was excited to use the space around the body as an active ingredient. This weave structure, which I now know as sprang, was also an outcome of my African trip. Seeing women weaving baskets in the market so quickly and dexterously, I was inspired to try one myself. Trying one in nylon was unsuccessful until I took away the uprights and then I discovered that the structure could be manipulated and changed. As you twist the Necklace/Veil around and around, it naturally becomes stiffer and more transparent. It was experimenting and using the nature of this structure that allowed me to create the piece.

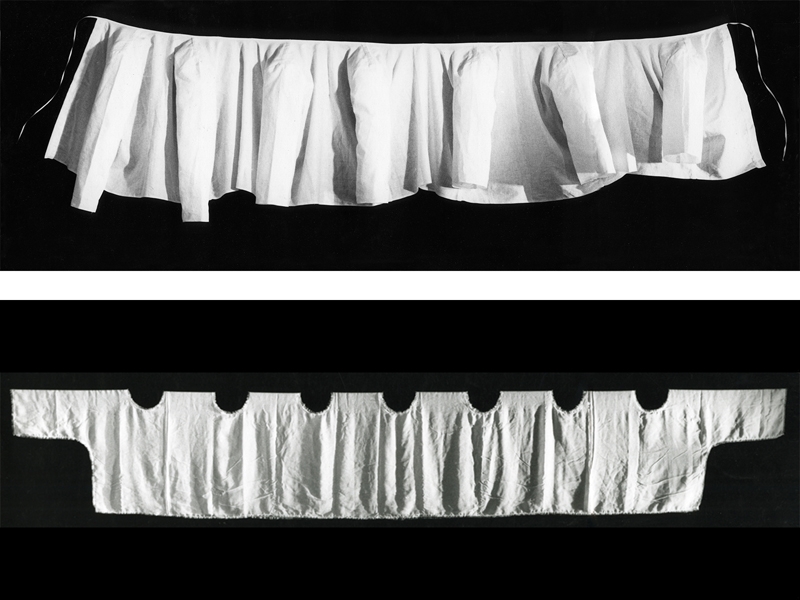

Your career started with a focus in jewelry and expanded to include larger work in textiles. Wraparound (1983) gives the viewer a sense of movement and repetition, as if an absent wearer had to repeatedly slip her arms into the sleeves in order to don the garment. What’s the story behind this work?

Caroline Broadhead: The journey from jewelry to clothing was a fairly logical development, though not a completely conscious one. The woven pieces—Necklace/Veil, Propellor, Sleeve—were taking over more space on the body and all had strong connotations with clothing. I was interested in the interaction, the handling, the performance of these works. Shirt with Long Sleeves and Wraparound were physical manifestations of a repeated gesture associated with getting dressed—pulling your sleeve up and putting the other arm in. I was interested in the idea of a jewelry piece or a garment looking like it couldn’t be worn, and then revealing its wearability through an image, a performance, or imagination. I was interested in objects that had more than one identity and objects that might inspire a particular movement or interaction.

Your work in textiles led to installation art and also collaborations with live performances. Was the transition from still object to space and movement a difficult one? Or an intuitive one?

Caroline Broadhead: This was actually a very natural progression. I had been demanding this sort of interaction from my work, but hadn’t quite figured out where that might lead. I started working with choreographers—Rosemary Lee, Claire Russ, and Angela Woodhouse—and those experiences opened up many possibilities of how space or a particular location could be used. And I liked the sense of occasion and time; when the performance was over, it was over.

How did your collaborations with these choreographers begin?

Caroline Broadhead: The South Bank Centre in London organized a couple of sessions inviting a number of choreographers, designers, artists, and dancers to come together for a day to discuss ideas and get to know one another, just to see what emerged. There was no agenda, and each smaller group of about four or five people had different ways of going about it. Although I wasn’t paired with Angela, it was how we heard about each other’s work. In 1991, I was invited to do a collaboration with Rosemary for Ballroom Blitz, a residency at the South Bank, which culminated with a performance. Rosemary and I had not met before, but the organizers thought our ideas would be aligned.

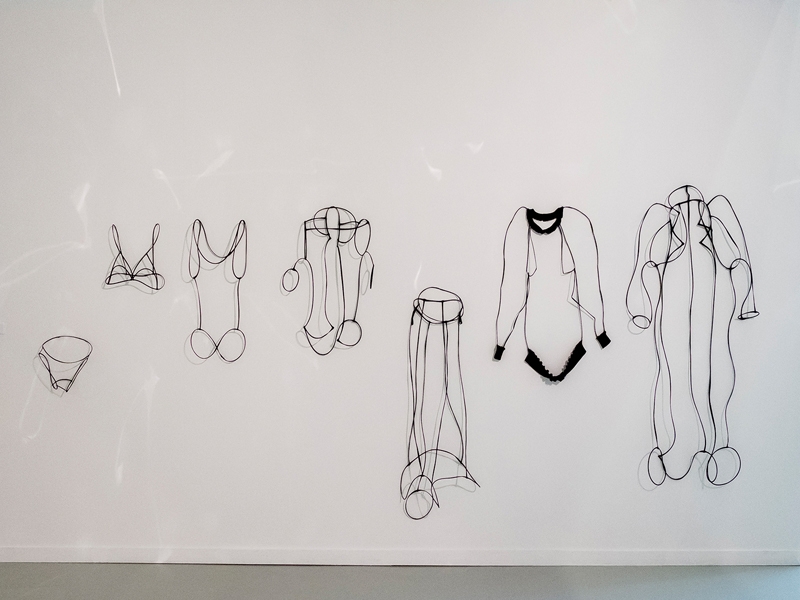

In Between (2011), a collaborative project with Angela Woodhouse and several dancers, one woman pulls on a string of pearls around her neck until it snaps. What themes were you exploring in this project?

Caroline Broadhead: Angela and I developed the dance performance Between to explore the relationship between dancer and audience and between clothing and skin. We were after moments of spectacle and combining these with intimate moments of proximity and touch. One such moment was when one dancer with gold leaf on her arm presses it into another’s skin, leaving a trace in the space and on the body of another. We played with notions of decorum and disruption, as the piece was performed in silence. The breaking of a pearl necklace, and particularly the sound of the beads scattering to the floor, created tension.

One common thread that runs through your 40-year career is the relationship between your work and the human body. What do you find fascinating about the body?

Caroline Broadhead: The body, or, more accurately, the person, runs as a concern through most of my work. It’s the experience of being human which is common to all of us and the biggest mystery. The idea of self, where one begins and ends, is fascinating. I’ve used jewelry, clothing, chairs, shadows, and reflections—all of which have a sense of presence, and they follow the dimensions of the body—and human relationships as a means of discovering something about ourselves.

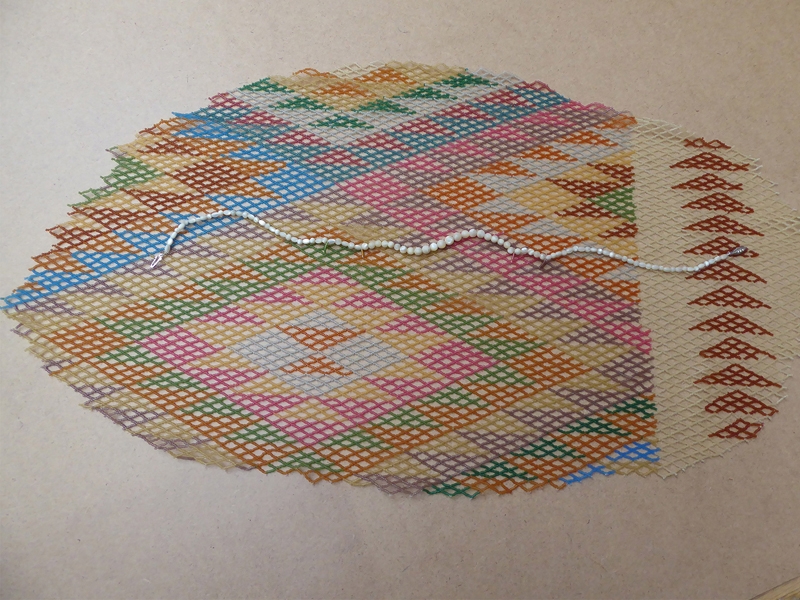

Your work Blanket for a Foundling (2014) is a moving portrait of loss. The blanket references pieces of cloth that parents left with the Foundling Hospital as they handed over their children. What was the thought process behind using glass beads and artificial pearls in the construction of this blanket?

Caroline Broadhead: The mothers left a token with their child so that it would be possible to identify them at a later date if their fortunes changed (only a very few children were claimed). These tokens ranged from a nut, a coin which was sometimes engraved or marked, or a small piece of jewelry. Most were not of intrinsic value. Artificial pearls have an “ambition” to be real. It was important for me that the necklace have a sad, abandoned feel, of low worth, but with the potential to have a sentimental significance. The double row of beads allowed a large gap when opened out.

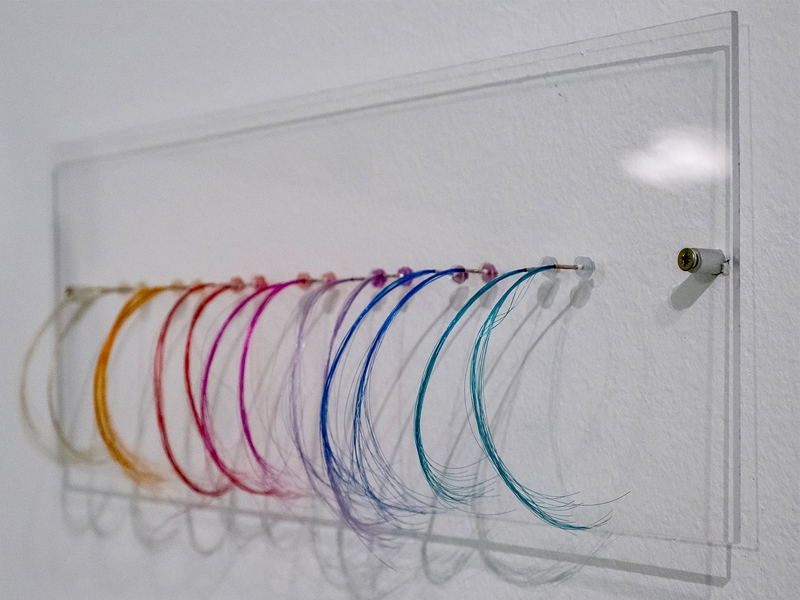

I had become fascinated with beads following a trip to Mexico. I like that glass beads are so available, they come in lots of colors and large quantities. Each tiny bead plays its own part in a greater whole. I like that beading is a repetitive process and one which takes time (however, I did have a wonderful intern helping with the making of this piece). The diamond pattern of the blanket was like the candlewick bedspread I had as a child, and it was the difference between this—a warm, comforting blanket and one which, although attractive to look at, gave neither warmth nor comfort, for glass is cold, breakable, and fragile—that interested me. There were many children given a place in the Foundling Hospital, and while they were safe there, fed and educated, their lives were friendless and harsh by standards today.

What exciting trends do you see in the contemporary jewelry field? Why do they spark your interest?

Caroline Broadhead: At the moment, there’s a proliferation of different styles, concerns, and ways of presenting jewelry, which is very healthy. What I respond to particularly is a strong sense of purpose, a clear way of communicating ideas, and an unusual way of handling materials. I also appreciate a sense of humor and wit.

What advice would you give to emerging jewelry artists who hope to build thriving, creative practices?

Caroline Broadhead: Keep having fun, follow your instincts and ideas that are exciting to you, be open to possibilities, and don’t be put off if things don’t go right immediately.

Have you seen or read anything of interest lately? Could you share your findings with our readers?

Caroline Broadhead: Just this weekend I went to see an exhibition in a beautiful building in London—Two Temple Place, which I had not known about before. The exhibition, Rhythm and Reaction: The Age of Jazz in Britain, included my great-uncle’s painting, The Breakdown. This painting was removed from the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition in 1926 after a complaint, after which he destroyed it and then repainted it many years later. I was very proud to see it.

I’m reading Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, by Yuval Noah Harari, which expounds ideas about how man is now taking control of things that before people thought were up to the gods, and putting forward scenarios of where that might take us.

Thank you! It was lovely interviewing you.