Adriane Dalton: To begin, Susan, tell our readers about the origins of your interest in studio jewelry.

Susan Grant Lewin: I started to develop a passion for the field when traveling to Scandinavia for my work as a journalist and while on assignment with the Walker Art Center. I was friendly with Bob Ebendorf at the time, and he really pushed me to write my first book, One of a Kind: American Art Jewelry Today (1994). Bob thought Europeans left Americans out of their shows and he urged me to build a case for American jewelers. The idea of the book was to show the world the depth and breadth of studio and contemporary jewelry in the U.S.

How did you expand and develop your relationship with jewelry beyond enthusiasm into the role of focused, informed collector?

Susan Grant Lewin: Like many jewelry enthusiasts, I woke up one day and realized, “Holy shit! I’m a collector.” Actually, I’m joking. I was pretty methodical. I studied the American scene in great depth while writing One of a Kind. There was so much great work being done in America. As I traveled around the US, writing the book and visiting the studios of the best American jewelers, I usually bought a piece or two. Who could resist?

My collection at first was very American-centric. Then I started traveling to Munich every year. I became friends with many of the top European artists and gallerists. Although I’m no longer writing about jewelry, I think like a journalist. I consider it essential to stay informed. Now I would say the collection is 50/50 between American and European artists.

What approaches did you take for developing your collection? To what extent are your selections about personal interest and to what extent are you concerned with preserving and promoting important works?

Susan Grant Lewin: Preserving the work and making it available to future generations was a primary focus. Just as when I was an architectural journalist at Hearst Magazines, I kept abreast of the most important practitioners and the young, rising stars that I wanted represented in my collection. I kept a list of artists I wanted to add to the collection. It wasn’t casual.

I very much wanted a museum to hold the collection. I could never care for it the way they do. Now it can inspire and inform many. This is so important for the artists I’ve collected, as the catalog and museum website are permanent records.

Ursula, as consulting curator and author of the catalog, describe for our readers your relationship to this collection, both in its development over the decades and the resulting exhibition.

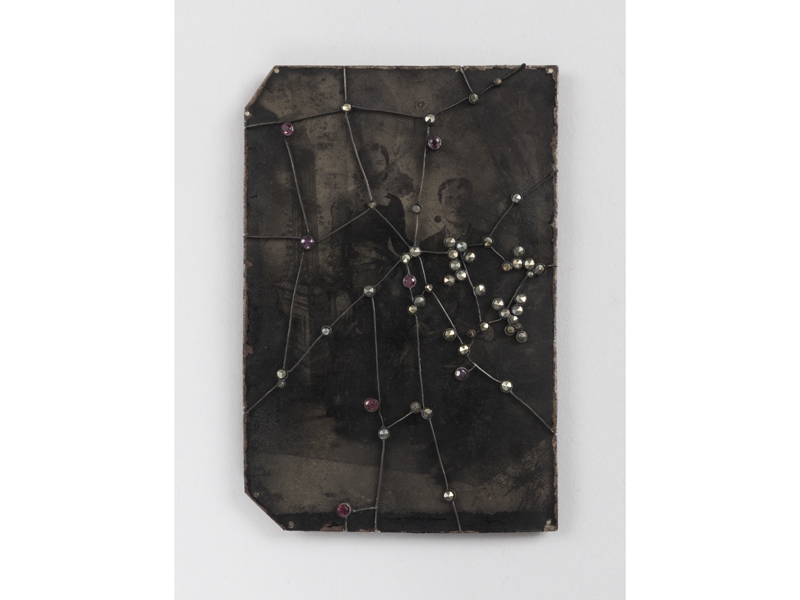

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: I met Susan soon after the Museum of Arts and Design appointed me the first curator of contemporary jewelry in the United States. For many years, Susan and I crisscrossed the globe together, hunting for art jewelry in galleries, exhibitions, and artist’s studios. On occasion we would passionately debate the purchase of a piece by an established jeweler or an emerging artist, but just as often Susan would jump right in and get a red dot on a piece within minutes of seeing it. Because we share an openness to new ideas and forms, her collection grew to reflect the pluralism of contemporary jewelry, more than its evolution. Nevertheless, Susan acquired a number of important historic works by pioneers of the studio jewelry movement, or “The New Jewelry” as it was then called in Europe, that add a rich contextual element to the more recent works that form the majority of the collection.

What was the process for selecting the works that make up this gift to the Cooper Hewitt?

Susan Grant Lewin: In a way I was the pre-curator, as I selected everything in my collection. Ursula had a specific agenda and she spent several weeks going over the collection, picking what she wanted for the show. The works selected were her choices.

I specifically bought the Doug Bucci necklace for the show. Even though I had some good examples of 3D printing, I felt I needed a spectacular one. His necklace filled that void in every way. I regret I never had an opportunity to wear it.

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: Susan presented us with a large illustrated checklist of all of the works in her collection that were available for donation. She generously allowed us to select 150 pieces, which I did over a period of several days in her New York apartment in consultation with Susan and the Cooper Hewitt curators, especially Sarah Coffin and Cindy Trope. We went first for the quality of an individual piece and for its significance to the field. I felt it was important to include works by pioneering jewelers of the 20th century, such as Art Smith or Torun Bülow-Hübe, to add a contextual framework. I also asked several of the artists for their drawings—not merely schematic working drawings but lovely works on their own. Other concerns were assuring that we had sufficient geographic balance (we included artists from 17 countries) and ample stylistic range to reflect the diversity and richness of contemporary jewelry.

Ursula, your catalog essay, “Born of Ideas,” contextualizes Susan’s collection within the breadth of the field in a manner that is comprehensive yet succinct. There are surely many lenses through which this collection can be examined; how did you set about framing these works that, as you state in the text, “resist rigid categorizations”?

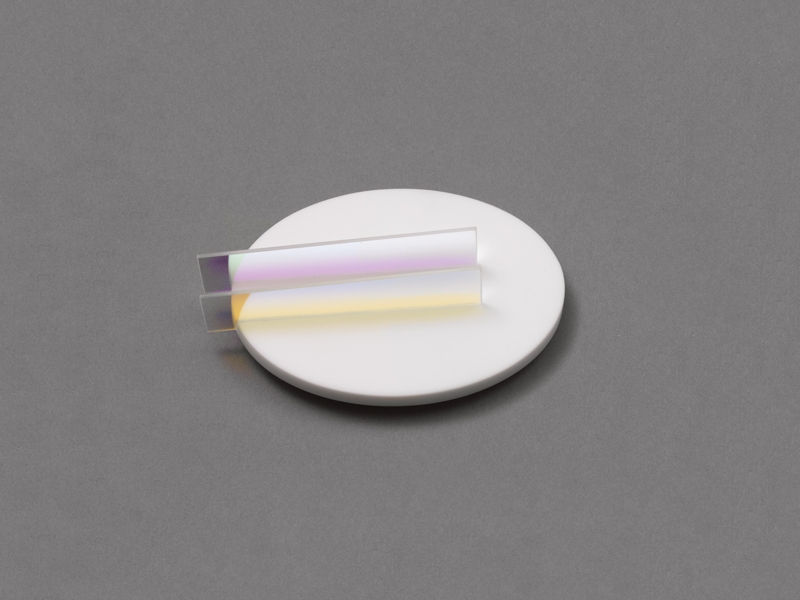

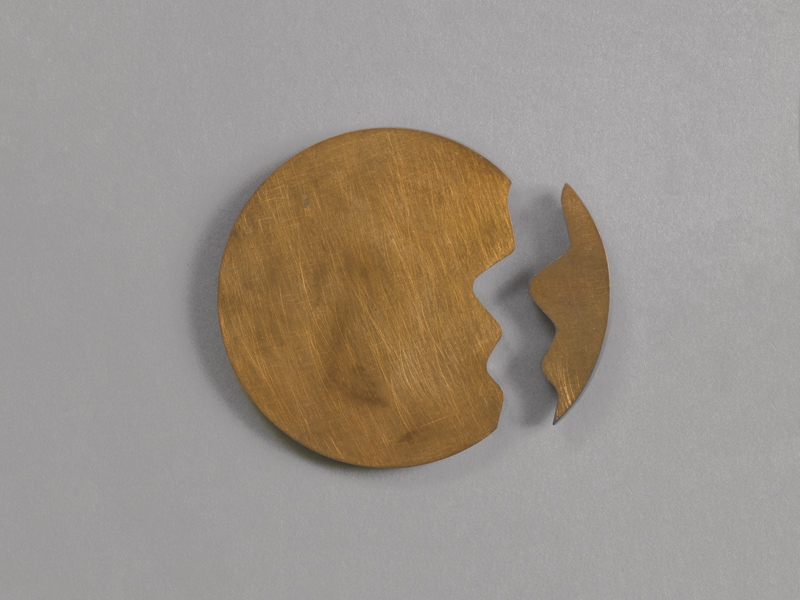

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: For me, materials or techniques are simply the means to an end, which is to convey the intent and concepts that motivated the artist. Although I separated the works very broadly into abstract and figurative groups—and several sub-categories—my major goal was to bring out the richness of the artistic ideas and the mastery with which these jewelers use diverse materials and techniques to support their ideas. The relationship with the human body is both a restraining commitment and a liberating force, much as brilliance can be achieved by composing within the demanding forms of a sonnet or haiku.

Across nearly all the works in the collection, nontraditional materials are employed to upend, muddy, and distort notions of preciousness and traditional forms. They are used to create high/low dichotomies (such as in Blinker Brooch, by Gijs Bakker), to make elegant forms economically accessible through nonprecious metals (as in Art Smith’s work) and altered or arranged in ways to obscure the original material (such as in works by Jiro Kamata and Thomas Gentille). An idea presented in Ursula’s essay, as well as in the statements from the artists, is that material can play a central role in democratizing jewelry. Can you elaborate on this idea as it relates to the collection and the broader field?

Susan Grant Lewin: Pushing boundaries and experimentation delights me. I know that when I take people through the show, the biggest fascination is always the materials. The few gold pieces, mostly from the Padua school, as wonderful as they are, seem old school. The use of nontraditional materials, for me, is a strong attraction to why I collect jewelry. Perhaps that is what drew me in my professional life to be the creative director of Formica Corporation. Commissioning works like Frank Gehry’s Fish was so exciting. Presenting him, and other architects and designers, with new materials was challenging and fun. Communicating with Frank, especially while he “played” with materials, delighted me.

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: Whereas the Dutch Smooth movement of the 1970s strove to make good design affordable through the use of common industrial materials and serial production, with the intent to democratize jewelry, most of today’s jewelry artists make unique one-offs that require time-consuming work and consummate skill. Similar to the designs of the Bauhaus that originally were destined for serial production for the middle classes but wound up as luxury designs, much of contemporary jewelry now is not made for consumption by the general public but for an exclusive niche field of connoisseurs. A good number of jewelers, especially in Holland, continue to fight this notion, however.

Although art jewelry has indeed redefined preciousness, the result is far from democratizing jewelry. Jewelers don’t necessarily have to risk their own financial resources to work with precious metals and gemstones, the worth of the materials has little or no relation to how a piece is valued, just as materials do not determine the value of paintings or sculpture. The increasing number of museum jewelry exhibitions has brought distinguished works to a wide audience and fostered the growth of enthusiastic and knowledgeable collectors, which has led to increasing prices for established artists. Even young jewelry makers right out of school are quoting prices exceeding $1,000, reflecting the investment they have made in perfecting their skills.

I don’t find that artists such as Jiro Kamata and Thomas Gentille obscure their raw materials. On the contrary, they explore them in great depth to bring out unexpected or subtle qualities in their component materials that range from technically sophisticated dichroic glass to natural eggshell.

In her process statement, Israeli artist Esther Knobel mentions her distaste for the trend of categorizing jewelry as “small sculpture” in order to elevate it as an art form. I wonder what your thoughts are on this as two people who are passionate about international art jewelry.

Susan Grant Lewin: This is a question I have mixed feelings about because when I try to explain the work to those unfamiliar with art jewelry, I sometimes need to compare it to sculpture. But jewelry is jewelry and sculpture is sculpture and they are different.

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: Esther Knobel belongs to a small group of Israeli jewelers, including Vered Kaminsky and Deganit Schocken, who in the 1990s set the ideological and intellectual foundation for Israeli contemporary jewelry. Esther remains firm in her belief that jewelry is not small sculpture since it is dependent on the body—whether there are sculptural or pictorial elements present or not. In my view, art jewelry at its best is conceived with the same motivations, ideas, and messages as those underpinning the visual arts in general, with the added interest that jewelry is designed with the human body in mind—either in a body-flattering or in a subversive manner. Many pieces are sculptural or painterly and can be shown off on the body, but they also embody concerns that are particular to jewelry and, in this regard, they partake in the canon of jewelry history with its own concerns particular to jewelry. To recognize this history is important.

While there were a number of famous artists, such as Picasso or, more recently, Anish Kapoor, who designed their jewelry as small-scale wearable objects along the lines of their larger pieces, with few exceptions they did not make their jewelry themselves and would not be considered jewelers per se.

What elements, either formally or conceptually, do you think are critical to successful works of art jewelry?

Susan Grant Lewin: The elements that are critical to a good piece of art jewelry differ so much. Last night I added a beautiful piece by Melanie Bilenker to my collection that is unlike anything I own. It is made of paper and human hair. She has been high on my list of artists whose work I want to own. I would say, like any art form, there is no set answer.

Ursula Ilse-Neuman: This is close to undefinable since it involves subjective reactions. Nevertheless, there are baselines that must be met. The piece should express its zeitgeist. Other essential characteristics include excellent workmanship—without which a jeweler’s ideas cannot be fully realized—compositional tension, balance of forms and materials, and innovative juxtapositions of colors, textures, and other physical attributes. But virtuosity in the use of materials and techniques as an end in itself is not sufficient for the creation of a successful piece.

Susan, what recommendations do you have for aspiring collectors?

Susan Grant Lewin: How each collector shapes their collection is very personal. No two collections are alike. My recommendation is to pick artists you like and try to get to know them. The dialogue will take you to good places. My friendship with Thomas Gentille strongly influenced my path as a collector. Getting to interact with gallerists was key. I always want to meet the artists, and the gallerists introduce me to their artists.

What are you reading lately, relevant to the field and otherwise?

Susan Grant Lewin: As to what I’m reading now, I bought a few wonderful jewelry books at the Cooper Hewitt bookstore. I especially like one about Ted Noten and one about Kadri Mälk. I’m very much into monographs and I like watching the evolution of an artist’s style.

Ursula Ilse-Neuman:

- Out of Place, the fascinating catalog of the 3rd Mediterranean Biennale in Sakhnin Valley (Israel) organized by Belu Fainaru; it documents and explains works of interesting Middle Eastern photographers, video artists, painters, and sculptors who exhibited in nontraditional places, such as butcher shops, garages, stone quarries, and even a mosque

- Pravu Mazumdar, a philosopher, writer, and teacher, whose long article called Wishful Thinking: On Hybridity, Human Nature and the Future of Jewelry examines the nature and future of art jewelry in relation to contemporary culture

- The Post-American World, by Fareed Zakaria, which explains the shifting role of the United States within the rapidly changing landscape of world affairs

- The Mind’s Eye, by Oliver Sacks. He writes about the many ways in which we experience the visual world and how we see in three dimensions

- The Illogic of Kassel, by Enrique Vila-Matas, in which a writer’s mission was to transform himself into a living art installation